Difference between revisions of "Norman Rockwell" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

Rockwell attended Chase Art School at the age of 16. He then went on to the National Academy of Design, and finally transferred, to the Art Students League, where he was taught by Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Both instructors instilled in their student a meticulous eye for detail and authenticity. Fogarty’s favorite admonition was that an illustration must be “an author’s words in paint.” There Rockwell developed a fascination with accurate anatomy and facial expressions, two hallmarks of his illustrations. | Rockwell attended Chase Art School at the age of 16. He then went on to the National Academy of Design, and finally transferred, to the Art Students League, where he was taught by Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Both instructors instilled in their student a meticulous eye for detail and authenticity. Fogarty’s favorite admonition was that an illustration must be “an author’s words in paint.” There Rockwell developed a fascination with accurate anatomy and facial expressions, two hallmarks of his illustrations. | ||

| − | His first job, and real breakthrough came in 1912, at age 18, when he landed a job while still an art student, illustrating C.H. Claudy's "Tell Me Why Stories.” These early illustrations were all done in black and white. During this time he also did illustrations for St. Nicholas Magazine, and the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), an organization that he would hold a long association with. | + | His first job, and real breakthrough came in 1912, at age 18, when he landed a job while still an art student, illustrating C.H. Claudy's "Tell Me Why Stories.” These early illustrations were all done in black and white. During this time he also did illustrations for St. Nicholas Magazine, and the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), an organization that he would hold a long association with. As a young illustrator he was an admirer of the chiefly children's illustrator, Howard Pyle who Rockwell called a "historian with a brush." His ambition, however, was to advance from the world of children's illustrations on to more challenging and adult material and themes. |

At age 19, in 1913, he became the art editor for Boys' Life, a post he held for several years. As part of fulfilling that position, he painted several covers between 1913 and 1915. His first published magazine cover, Scout at Ship's Wheel, appeared on the Boys' Life September 1913 edition. | At age 19, in 1913, he became the art editor for Boys' Life, a post he held for several years. As part of fulfilling that position, he painted several covers between 1913 and 1915. His first published magazine cover, Scout at Ship's Wheel, appeared on the Boys' Life September 1913 edition. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

===World War II and the Four Freedoms Series=== | ===World War II and the Four Freedoms Series=== | ||

[[Image:Rockwell studio rear.jpg|thumb|250px|The rear of Norman Rockwell's preserved studio.]] | [[Image:Rockwell studio rear.jpg|thumb|250px|The rear of Norman Rockwell's preserved studio.]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | That same year a [[fire]] in his studio destroyed numerous original paintings, costumes, and props. Later, in 1953, his wife Mary died unexpectedly, which resulted in Rockwell taking time off to grieve. It was during this break that he and his son Thomas produced his [[autobiography]], ''My Adventures as an Illustrator'', which was published in 1960. The ''Post'' printed excerpts from this book in eight consecutive issues, the first containing Rockwell's famous ''Triple Self-Portrait''. | + | In 1943, during the Second World War, Rockwell, too old to enlist, decided to contribute to the war effort by drawing “posters.” Initially, rejected by the U.S. Government, Post editor, Ben Hibbon encouraged him to paint his idea of the Four Freedoms, but not just as covers. Rockwell received inspiration for the paintings from [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]]’s [http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/fdrthefourfreedoms.htm speech]who had declared that there were four principles for universal rights: Freedom from Want, Freedom of Speech, Freedom to Worship, and Freedom from Fear. How to translate the lofty ideals of the speech into specific art was Rockwell’s initial challenge. He received the idea for the first painting, ''Freedom of Speech'' when he observed one of his neighbors stand up to speak at a town hall meeting in Vermont. This was, in the end, to be his favorite painting. Rockwell ended up using other Vermont neighbors as models for the Four Freedoms series. |

| + | |||

| + | He wrestled mightly with the project which took him seven months to complete and during which time he lost fifteen pounds. However, the end result was that the pictures were reproduced and requested around the world. ''Freedom to Worship'' shows a diverse gathering praying in different forms under the heading, “ Each according to the dictates of his own conscience.” Rockwell was never able to remember where he read the quote or who it was attributable to but most would deem it appropos. ''Freedom From Fear'' shows parents tucking their children in to bed safe at night, and ''Freedom from Want'' is of a Thanksgiving dinner. In fact, it was his own Thanksgiving dinner and Rockwell said it was one of the only times he ate the model when he was finished painting it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The paintings were published in 1943 by The Saturday Evening Post. The U.S. Treasury Department later promoted war bonds by exhibiting the originals in 16 cities. Ben Hibbon, of the Post said of them “they are the greatest human documents........... | ||

| + | |||

| + | That same year a [[fire]] in his studio destroyed numerous original paintings, costumes, and props. Later, in 1953, his wife Mary died unexpectedly, which resulted in Rockwell taking time off to grieve. It was during this break that he and his son Thomas produced his [[autobiography]], ''My Adventures as an Illustrator'', which was published in 1960. The ''Post'' printed excerpts from this book in eight consecutive issues, the first containing Rockwell's famous ''Triple Self-Portrait''. | ||

===Look Magazine and Social Issues=== | ===Look Magazine and Social Issues=== | ||

Revision as of 22:11, 27 November 2006

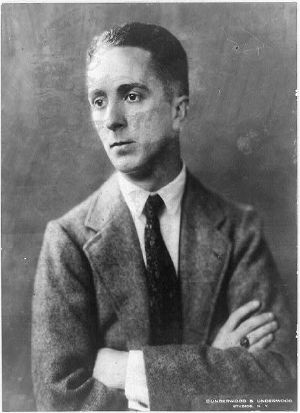

Norman Percevel Rockwell (February 3, 1894 – November 8, 1978) was one of the most famous and admired American illustrators and painters of the 20th century. His works enjoy a broad popular appeal and his greatest legacy, and perhaps what he is most remembered for, were the Saturday Evening Post magazine covers that he illustrated for more than four decades.

His prodigious career, without necessarily intending to, chronicled American history from World War II through space exploration. And although, most of his themes were about everyday people performing everyday minutia, from saying grace to going fishing, to playing baseball, later works reflected the social consciousness of the 60s.

He was sometimes criticized for painting pictures overly saccharine and idealized. However, Rockwell was noted for being visually accurate as evidenced by his masterfully detailed portraits. He once commented unpretentiously about the purpose of his art, “Without thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed. My fundamental purpose is to interpret the typical American. I am a story teller.”

Biography

Childhood

He was born on February 3, 1894 in New York City to Jarvis Waring and Ann Mary (Hill) Rockwell. He had one sibling, a brother, Jarvis. Rockwell’s family, of modest means, lived in an apartment on the Upper West side. His father, proud of their English heritage, used to read from Charles Dickens to he and his brother on Sundays. Rockwell would sit and sketch pictures of the various and colorful characters from books like Oliver Twist. Both his view of the world and his powers of observation were greatly affected by the stories of Dickens. His family would spend summers away from the city, a welcome respite for young Rockwell. Throughout most of his life he eschewed cityscapes while pastoral and country themes were to be a continuing motif in his paintings.

Rockwell attended Chase Art School at the age of 16. He then went on to the National Academy of Design, and finally transferred, to the Art Students League, where he was taught by Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Both instructors instilled in their student a meticulous eye for detail and authenticity. Fogarty’s favorite admonition was that an illustration must be “an author’s words in paint.” There Rockwell developed a fascination with accurate anatomy and facial expressions, two hallmarks of his illustrations.

His first job, and real breakthrough came in 1912, at age 18, when he landed a job while still an art student, illustrating C.H. Claudy's "Tell Me Why Stories.” These early illustrations were all done in black and white. During this time he also did illustrations for St. Nicholas Magazine, and the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), an organization that he would hold a long association with. As a young illustrator he was an admirer of the chiefly children's illustrator, Howard Pyle who Rockwell called a "historian with a brush." His ambition, however, was to advance from the world of children's illustrations on to more challenging and adult material and themes.

At age 19, in 1913, he became the art editor for Boys' Life, a post he held for several years. As part of fulfilling that position, he painted several covers between 1913 and 1915. His first published magazine cover, Scout at Ship's Wheel, appeared on the Boys' Life September 1913 edition.

Saturday Evening Post

During the First World War, when he first attempted to enlist in the U.S. Navy, he was refused entry because, at 6 feet (1.83 m) tall and 140 pounds (64 kg), he was eight pounds underweight. So, on a doctor’s suggestion and a friend's dare, he spent one night gorging himself on bananas, liquids and donuts, and weighed enough to enlist the next day. He was given the role of a military artist and proceeded to paint pictures of soldiers, which he did with the intent of bolstering morale.

He reflected in his autobiography (ref?) that it was often hard to come up with ideas for pictures that everyone would like but pictures of war were universally regarded. His picture of a soldier returning from war after World War II (Homecoming G. I., Post cover, 1945) was displayed in various places all over the nation. Rockwell did not explicitly paint war scenes; rather he chose to capture and immortalize the tender moments, the small scenes, such as the returning G.I. being greeted at the fire escape by family, friends and neighbors (including the dog!) Soldiers and sailors were to be one of Rockwell’s recurring themes. In fact, he once commented that when he was having trouble with a picture he would add a puppy to it.

Rockwell moved to New Rochelle, New York at age 21 and shared a studio with the cartoonist Clyde Forsythe, who worked for The Saturday Evening Post. With Forsythe's help, he submitted his first successful cover painting to the Post in 1916, Boy with Baby Carriage. He followed that success with Circus Barker and Strongman (published on June 3), Gramps at the Plate (August 5), Redhead Loves Hatty Perkins (September 16), and Man Playing Santa (December 9). Rockwell was published a total of eight times on Post covers within twelve months of his first submission. Norman Rockwell went on to publish a remarkable 321 more covers for The Saturday Evening Post over the next 47 years.

Rockwell's success on the cover of the Post led to covers for other magazines of the day, most notably The Literary Digest, The Country Gentleman, Leslie's, Judge, Peoples Popular Monthly and Life magazine.

Rockwell married his first wife, Irene O'Connor, in 1916. Irene was Rockwell's model in Mother Tucking Children into Bed, published on the cover of The Literary Digest on January 19, 1921. Although the couple were a part of the social mileu of New Rochelle, they were never really happy together. After fourteen years of marriage and no children they went their separate ways. Rockwell soon remarried schoolteacher Mary Barstow, with whom he had three children: Jarvis , Thomas, and Peter. Although Rockwell worked seven days a week and long hours, Mary shared in Rockwell's passion for his art. She was often involved in ideas, observations, and feedback as Rockwell could be a meticulous perfectionist. In 1939, the Rockwell family moved to Arlington, Vermont, which provided him with the inspiration to paint the scenes of American small town life that he was to become so well known for.

World War II and the Four Freedoms Series

In 1943, during the Second World War, Rockwell, too old to enlist, decided to contribute to the war effort by drawing “posters.” Initially, rejected by the U.S. Government, Post editor, Ben Hibbon encouraged him to paint his idea of the Four Freedoms, but not just as covers. Rockwell received inspiration for the paintings from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s speechwho had declared that there were four principles for universal rights: Freedom from Want, Freedom of Speech, Freedom to Worship, and Freedom from Fear. How to translate the lofty ideals of the speech into specific art was Rockwell’s initial challenge. He received the idea for the first painting, Freedom of Speech when he observed one of his neighbors stand up to speak at a town hall meeting in Vermont. This was, in the end, to be his favorite painting. Rockwell ended up using other Vermont neighbors as models for the Four Freedoms series.

He wrestled mightly with the project which took him seven months to complete and during which time he lost fifteen pounds. However, the end result was that the pictures were reproduced and requested around the world. Freedom to Worship shows a diverse gathering praying in different forms under the heading, “ Each according to the dictates of his own conscience.” Rockwell was never able to remember where he read the quote or who it was attributable to but most would deem it appropos. Freedom From Fear shows parents tucking their children in to bed safe at night, and Freedom from Want is of a Thanksgiving dinner. In fact, it was his own Thanksgiving dinner and Rockwell said it was one of the only times he ate the model when he was finished painting it.

The paintings were published in 1943 by The Saturday Evening Post. The U.S. Treasury Department later promoted war bonds by exhibiting the originals in 16 cities. Ben Hibbon, of the Post said of them “they are the greatest human documents...........

That same year a fire in his studio destroyed numerous original paintings, costumes, and props. Later, in 1953, his wife Mary died unexpectedly, which resulted in Rockwell taking time off to grieve. It was during this break that he and his son Thomas produced his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, which was published in 1960. The Post printed excerpts from this book in eight consecutive issues, the first containing Rockwell's famous Triple Self-Portrait.

Look Magazine and Social Issues

Rockwell married his third wife, retired schoolteacher Molly Punderson, in 1961. His last painting for the Post was published in 1963, marking the end of a publishing relationship that had included 321 cover paintings. He spent the next 10 years painting for Look Magazine, where his work depicted his interests in civil rights, poverty and space exploration. One of Rockwell's last major works was in 1969 when he painted a portrait of the beloved actress and singer Judy Garland as Dorothy in "The Wizard of Oz" shortly after her death. This portrait is now in the collection of the Motion Picture Country House and Hospital.

During his long career, he was commissioned to paint the portraits for Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, as well as those of other world figures, including Gamal Abdel Nasser and Jawaharlal Nehru.

Norman's ability to "get the point across" in one picture, and his flair for painstaking detail made him a favorite of the advertising industry. He was also commissioned to illustrate over 40 books including the ever-popular Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. His annual contributions for the Boy Scouts' calendars (1925 – 1976), were only slightly overshadowed by his most popular of calendar works: the "Four Seasons" illustrations for Brown & Bigelow that were published for 17 years beginning in 1947. and reproduced in various styles and sizes since 1964. Illustrations for booklets, catalogs, posters (particularly movie promotions), sheet music, stamps, playing cards, and murals (including "Yankee Doodle Dandy", which was completed in 1936 for the Nassau Inn in Princeton, New Jersey) rounded out Rockwell's œuvre as an illustrator. In his later years, Rockwell began receiving more attention as a painter when he chose more serious subjects such as the series on racism for Look. Another late career painting, Shuffleton's Barber Shop is considered by many critics to be one of his masterpieces.

Legacy

A custodianship of 574 of his original paintings and drawings was established with Rockwell's help near his home in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and the museum is still open today year round http://www.nrm.org. Rockwell received in 1977 the Presidential Medal of Freedom for "vivid and affectionate portraits of our country", the United States of America's highest civilian honor.

Rockwell is a recipient of the Silver Buffalo Award, the highest adult award given by the Boy Scouts of America.

Norman Rockwell died November 8, 1978 of emphysema at age 84 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts

Critique of his work

Rockwell was very prolific, and produced over 4000 original works, most of which have been either destroyed by fire or are in permanent collections. Original magazines in mint condition that contain his work are extremely rare and can command thousands of dollars today.

Many of his works appear overly sweet in modern critics' eyes, especially the Saturday Evening Post covers, which tend toward idealistic or sentimentalized portrayals of American life—this has led to the often-depreciatory adjective Rockwellesque. Consequently, Rockwell is not considered a "serious painter" by some contemporary artists, who often regard his work as bourgeois and kitsch. Writer Vladmir Nabokov scorned brilliant technique put to 'banal' use, and wrote in his book Pnin; "That Dalí is really Norman Rockwell's twin brother kidnapped by gypsies in babyhood". He is called an "illustrator" instead of an artist by some critics, a designation he did not mind, as it was what he called himself. Yet, Rockwell sometimes produced images considered powerful and moving to anyone's eye. One example is The Problem We All Live With, which dealt with the issue of school integration. The painting depicts a young African American girl, Ruby Bridges, flanked by white federal marshals, walking to school past a wall defaced by racist graffiti. It is probably not an image that could have appeared on a magazine cover earlier in Rockwell's career, but it ranks among his best-known works today.

Major works

- Scout at Ship's Wheel (1913) [1]

- Santa and Scouts in Snow (1913) [2]

- Boy and Baby Carriage (1916) [3]

- Circus Barker and Strongman (1916) [4]

- Gramps at the Plate (1916) [5]

- Redhead Loves Hatty Perkins (1916) [6]

- People in a Theatre Balcony (1916) [7]

- Cousin Reginald Goes to the Country (1917) [8]

- Santa and Expense Book (1920) [9]

- Mother Tucking Children into Bed (1921) [10]

- No Swimming (1921) [11]

- The Four Freedoms (1943) [12]

- Freedom of Speech (1943) [13]

- Freedom to Worship (1943) [14]

- Freedom from Want (1943) [15]

- Freedom from Fear (1943) [16]

- Rosie the Riveter (1943) [17]

- Going and Coming (1947)

- Bottom of the Sixth (1949) [18]

- Saying Grace (1951)

- Girl at Mirror (1954)

- Breaking Home Ties (1954) [19]

- The Marriage License (1955)

- The Scoutmaster (1956)[20]

- Triple Self-Portrait (1960) [21]

- Golden Rule (1961)

- The Problem We All Live With (1964) [22]

- New Kids in the Neighborhood (1967)

- The Rookie

- Judy Garland (1969)

External links

- Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Massachusetts

- The Rockwell Gallery Collection

- Norman Rockwell Museum of Vermont

- Norman Rockwell official web site

- Complete Image Archive of Post-1922 Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post Covers

- Complete Descriptive Index of Norman Rockwell Magazine Covers

- Norman Rockwell WWII posters, hosted by the University of North Texas Libraries Digital Collections

- Complete Descriptive Index of Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post covers

- Norman Rockwell at Find a Grave

- Shea, Christopher, "Portrait of the artist as a dirty old man", The Boston Globe, October 1, 2006.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.