Mutiny

Mutiny is the act of conspiring to disobey an order that a group of similarly-situated individuals (typically members of the military; or the crew of any ship, even if they are civilians) are legally obliged to obey. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members of the military against their superior officer(s.

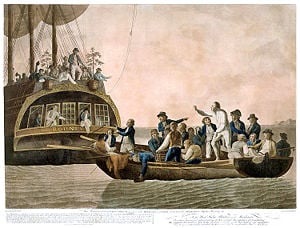

During the Age of Discovery, mutiny particularly meant open rebellion against a ship’s captain. This occurred, for example, during Magellan’s journey, resulting in the killing of one mutineer, the execution of another and the marooning of two others, and on Henry Hudson’s Discovery, resulting in Hudson and others being set adrift in a boat.

Reasons and relevance

While many mutinies were carried out in response to backpay and/or poor conditions within the military unit or on the ship, some mutinies, such as the Connaught Rangers mutiny and the Wilhelmshaven mutiny, were part of larger movements or revolutions.

In times and cultures where power 'comes from the barrel of a gun', rather than through a constitutional mode of succession (such as hereditary monarchy or elections), a major mutiny, especially in the capital, often leads to a change of ruler, sometimes even a new regime, and may therefore be induced by ambitious politicians hoping to replace the incumbent; e.g. many Roman emperors seized power at the head of a mutiny or were put on the throne after a successful one. A special case are palace revolutions, in which the guards often play a decisive role- again, many Roman emperors owed their throne to the Pretorian Guard.

Penalty

Most countries still punish mutiny with particularly harsh penalties, sometimes even the death penalty. Mutiny is typically thought of only in a shipboard context, but many countries’ laws make no such distinction, and there have been notable mutinies on land (see below).

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, until 1689 mutiny was regulated by Articles of War, instituted by the monarch and effective only in a period of war. In 1689, the first Mutiny Act was passed, passing the responsibility to enforce discipline within the military to Parliament. The Mutiny Act, altered in 1803, and the Articles of War defined the nature and punishment of mutiny, until the latter were replaced by the Army Discipline and Regulation Act in 1879. This, in turn, was replaced by the Army Act in 1881.[1]

The Royal Navy’s Articles of War have changed slightly over the centuries they have been in force, but the 1757 version is representative — except that the death penalty no longer exists — and defines mutiny thus:

Article 19: If any person in or belonging to the fleet shall make or endeavor to make any mutinous assembly upon any pretence whatsoever, every person offending herein, and being convicted thereof by the sentence of the court martial, shall suffer death: and if any person in or belonging to the fleet shall utter any words of sedition or mutiny, he shall suffer death, or such other punishment as a court martial shall deem him to deserve: and if any officer, mariner, or soldier on or belonging to the fleet, shall behave himself with contempt to his superior officer, being in the execution of his office, he shall be punished according to the nature of his offence by the judgment of a court martial.

Article 20: If any person in the fleet shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous practice or design, being convicted thereof by the sentence of a court martial, he shall suffer death, or any other punishment as a court martial shall think fit; and if any person, in or belonging to the fleet, shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous words spoken by any, to the prejudice of His Majesty or government, or any words, practice, or design, tending to the hindrance of the service, and shall not forthwith reveal the same to the commanding officer, or being present at any mutiny or sedition, shall not use his utmost endeavours to suppress the same, he shall be punished as a court martial shall think he deserves.[2]

The military law of England in early times existed, like the forces to which it applied, in a period of war only. Troops were raised for a particular service, and were disbanded upon the cessation of hostilities. The crown, by prerogative, made laws known as Articles of War, for the government and discipline of the troops while thus embodied and serving. Except for the punishment of desertion, which was made a felony by statute in the reign of Henry VI, these ordinances or Articles of War remained almost the sole authority for the enforcement of discipline until 1689, when the first Mutiny Act was passed and the military forces of the crown were brought under the direct control of parliament. Even the Parliamentary forces in the time of Charles I and Oliver Cromwell were governed, not by an act of the legislature, but by articles of war similar to those issued by the king and authorized by an ordinance of the Lords and Commons, exercising in that respect the sovereigu prerogative. This power of law-making by prerogative was however held to be applicable during a state of actual war only, and attempts to exercise it in time of peace were ineffectual. Subject to this limitation it existed for considerably more than a century after the passing of the first Mutiny Act.

From 1689 to 1803, although in peace time the Mutiny Act was occasionally suffered to expire, a statutory power was given to the crown to make Articles of War to operate in the colonies and elsewhere beyond the seas in the same manner as those made by prerogative operated in time of war.

In 1715, in consequence of the rebellion, this power was created in respect of the forces in the kingdom, but apart from and in no respect affected the principle acknowledged all this timethat the crown of its mere prerogative could make laws for the government of the army in foreign countries in time of war.

The Mutiny Act of 1803 effected a great constitutional change in this respect: the power of the crown to make any Articles of War became altogether statutory, and the prerogative merged in the act of parliament. The Mutiny Act 1873 was passed in this manner.

So matters remained till 1879, when the last Mutiny Act was passed and the last Articles of War were promulgated. The Mutiny Act legislated for offences in respect of which death or penal servitude could be awarded, and the Articles of War, while repeating those provisions of the act, constituted the direct authority for dealing with offences for which imprisoument was the maximum punishment as well as with many matters relating to trial and procedure.

The act and the articles were found not to harmonize in all respects. Their general arrangement was faulty, and their language sometimes obscure. In 1869 a royal commission recommended that both should be recast in a simple and intelligible shape. In 1878 a committee of the House of Commons endorsed this view and made recommendations as to how the task should be performed. In 1879 passed into law a measure consolidating in one act both the Mutiny Act and the Articles of War, and amending their provisions in certain important respects. This measure was called the Army Discipline and Regulation Act 1879.

After one or two years experience finding room for improvement, it was superseded by the Army Act 1881, which hence formed the foundation and the main portion of the military law of England, containing a proviso saving the right of the crown to make Articles of War, but in such a manner as to render the power in effect a nullity by enacting that no crime made punishable by the act shall be otherwise punishable by such articles. As the punishment of every conceivable offence was provided, any articles made under the act could be no more than an empty formality having no practical effect.

Thus the history of English military law up to 1879 may be divided into three periods, each having a distinct constitutional aspect: (I) prior to 1689, the army, being regarded as so many personal retainers of the sovereign rather than servants of the state, was mainly governed by the will of the sovereign; (2) between 1689 and 1803, the army, being recognized as a permanent force, was governed within the realm by statute and without it by the prerogative of the crown and (3) from 1803 to 1879, it was governed either directly by statute or by the sovereign under an authority derived from and defined and limited by statute. Although in 1879 the power of making Articles of War became in effect inoperative, the sovereign was empowered to make rules of procedure, having the force of law, to regulate the administration of the act in many matters formerly dealt with by the Articles of War. These rules, however, must not be inconsistent with the provisions of the Army Act itself, and must be laid before parliament immediately after they are made. Thus in 1879 the government and discipline of the army became for the first time completely subject either to the direct action or the close supervision of parliament.

A further notable change took place at the same time. The Mutiny Act had been brought into force on each occasion for one year only, in compliance with the constitutional theory:

that the maintenance of a standing army in time of peace, unless with the consent of parliament, is against law. Each session therefore the text of the act had to be passed through both Houses clause by clause and line by line. The Army Act, on the other hand, is a fixed permanent code. But constitutional traditions are fully respected by the insertion in it of a section providing that it shall come into force only by virtue of an annual act of parliament. This annual act recites the illegality of a standing army in time of peace unless with the consent of parliament, and the necessity nevertheless of maintaining a certain number of land forces (exclusive of those serving in India) and a body of royal marine forces on shore, and of keeping them in exact discipline, and it brings into force the Army Act for one year.[3]

Section 21(5) of the 1998 Human Rights Act completely abolished the death penalty in the United Kingdom. Previously to this, the death penalty had already been abolished for murder, but it remained in force for certain military offences, including mutiny, although these provisions had not been used for several decades.[4]

This provision was not required by the European Convention on Human Rights. Protocol 6 of the Convention permits the death penalty for certain military offences and protocol 13, which prohibits the death penalty for all circumstances, did not then exist. The UK government introduced s. 21(5) as a late amendment in response to parliamentary pressure.

United States

The United States’ Uniform Code of Military Justice defines mutiny thus:

- Art. 94. (§ 894.) Mutiny or Sedition.

- (a) Any person subject to this code (chapter) who—

- (1) with intent to usurp or override lawful military authority, refuses, in concern with any other person, to obey orders or otherwise do his duty or creates any violence or disturbance is guilty of mutiny;

- (2) with intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of lawful civil authority, creates, in concert with any other person, revolt, violence, or other disturbance against that authority is guilty of sedition;

- (3) fails to do his utmost to prevent and suppress a mutiny or sedition being committed in his presence, or fails to take all reasonable means to inform his superior commissioned officer or commanding officer of a mutiny or sedition which he knows or has reason to believe is taking place, is guilty of a failure to suppress or report a mutiny or sedition.

- (b) A person who is found guilty of attempted mutiny, mutiny, sedition, or failure to suppress or report a mutiny or sedition shall be punished by death or such other punishment as a court-martial may direct.[5]

Uniform Code of Military Justice, Art. 94; 10 U.S.C. § 894 (2004). [Note — items in parentheses replace the items immediately preceding, as provided in the codified statutory version of the Uniform Code, located at title 10, chapter 47 of the United States Code.]

U.S. military law requires obedience only to lawful orders. Disobedience to unlawful orders is the obligation of every member of the U.S. armed forces, a principle established by the Nuremberg trials and reaffirmed in the aftermath of the My Lai Massacre. However, a U.S. soldier who disobeys an order after deeming it unlawful will almost certainly be court-martialed to determine whether the disobedience was proper.

There have been many incidents of resistance on the part of soldiers serving in Iraq. In October 2004 members of the US Army’s 343rd Quartermaster Company refused orders in Iraq. (Specifically, they were ordered to deliver fuel from one base to another, along an extremely dangerous route, in vehicles with little to no armor. The soldiers argued that obeying orders would have resulted in heavy casualties. Furthermore, the fuel in question was allegedly contaminated and useless.)[6] From 2002 to 2003, according to military records, conscientious objection (CO) applications tripled for the Army and quadrupled for the Marines, the two branches most involved in combat in Iraq.[7]. Legal authorities do not typically regard these as examples of mutiny, as such.

Famous mutinies

17th century

- Batavia was a ship of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), built in 1628 in Amsterdam, which was struck by mutiny and shipwreck during her maiden voyage.

- Corkbush Field mutiny occurred on 1647 during the early stages the Second English Civil War.

18th century

- HMS Hermione was a 32-gun fifth-rate frigate of the British Royal Navy, launched in 1782, notorious for the mutiny which took place aboard her.

- Mutiny on the Bounty happened aboard a British Royal Navy ship in 1789 that has been made famous by several books and films.

- Spithead and Nore mutinies were two major mutinies by sailors of the British Royal Navy in 1797

19th century

- The Indian rebellion of 1857 was a period of armed uprising in India against British colonial power, and was popularly remembered in Britain as the Sepoy Mutiny .

20th century

- Russian battleship Potemkin was made famous by a rebellion of the crew against their oppressive officers in June of 1905 during the Russian Revolution of 1905.

- Curragh Incident of July 20, 1914 occurred in the Curragh, Ireland, where British soldiers protested against enforcement of the Home Rule Act 1914.

- French Army mutinies in 1917. The failure of the Nivelle offensive in April and May 1917 resulted in widespread mutiny in many units of the French Army.

- Wilhelmshaven mutiny broke out in the German High Seas Fleet on 29 October 1918. The mutiny ultimately led to the end of the First World War, to the collapse of the Monarchy and to the establishment of the Weimar Republic.

- Kronstadt rebellion was an unsuccessful uprising of Soviet sailors, led by Stepan Petrichenko, against the government of the early Russian SFSR in the first weeks of March in 1921. It proved to be the last major rebellion against Bolshevik rule.

- Invergordon Mutiny was an industrial action by around a thousand sailors in the British Atlantic Fleet, that took place on 15-16 September 1931. For two days, ships of the Royal Navy at Invergordon were in open mutiny, in one of the few military strikes in British history.

- Cocos Islands Mutiny was a failed mutiny by Sri Lankan servicemen on the then-British Cocos (Keeling) Islands during the Second World War.

- Port Chicago mutiny on August 9 1944, three weeks after the Port Chicago disaster, 258 out of the 320 African-American sailors in the ordnance battalion refused to load any ammunition.

- The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny encompasses a total strike and subsequent mutiny by the Indian sailors of the Royal Indian Navy on board ship and shore establishments at Bombay (Mumbai) harbour on 18 February 1946.

- SS Columbia Eagle incident occurred during the Vietnam War when sailors aboard an American merchant ship mutinied and hijacked the ship to Cambodia.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ British Public Statutes Affected. Irish Statute Books. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ The Articles of War - 1757 HMSRichmond.org. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ An Historical Sketch of Military Law JStor. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Human Rights Act 1998 Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Uniform Code of Military Justice US Army. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Orders Refused. AlterNet. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Breaking the Code of Silence In These Times. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

External Links

- History page of mutinies and wars - a collection of short histories

- - G.I. Resistance to the Vietnam War

- Mutinies in World War One by David Lamb

- Leonard F. Guttridge, Mutiny: A History of Naval Insurrection, United States Naval Institute Press, 1992, ISBN 0-87021-281-8

- [1]Sea Your History- Royal Naval Museum

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.