Montanism

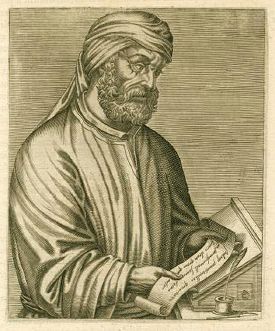

Montanism was an early Christian sectarian movement beginning in the mid-2nd century CE, named after its founder Montanus. It's defining characteristic was a belief that its founder, together with the two prophetesses Priscilla and Miximilla, were in special and direct communion with the Holy Spirit. It flourished in and around the region of Phrygia, and also spread to other regions in the Roman Empire before Christianity was generally tolerated or legal. Strongly devoted to and spiritual purity, refusing any compromise with the secular authority, the Montanists counted many martyrs among their adherents. No less an intellectual power than the otherwise orthodox Tertullian supported their cause and beliefs.

Although the bishops eventually declared Montanism to be a heresy, the sect persisted well into the fourth century and continued in some places for another three or four hundred years.

The condemnation of Montanism by the orthodox Church put a virtual end to the tradition of Christian prophecy. Thereafter, recognized Christian prophets would be few and far between. Because of its practice of esctatic communion with the Spirit and its claim of continuing revelation through its prophets, some people have drawn parallels between Montanism and Pentecostalism.

History

No original works of the early Montanists survive. For the most part we must rely on the opinions of their opponents — together with Tertuallian's later works — to piece together their history. That they constituted a challenge to epsicopal authority is clear. That their theological doctrines were otherwise heretical is debatable.

Shortly after Montanus' conversion to Christianity, he began travelling among the rural settlements of Asia Minor, preaching and testifying. Montanus was accompanied by two women, Prisca, sometimes called Priscilla, and Maximilla, who allegedly purported to be the embodiments of the Holy Spirit that moved and inspired them. When she was excommunicated, she exclaimed "I am driven away like the wolf from the sheep. I am no wolf: I am word and spirit and power." Prisca claimed that Christ had appeared to her in female form, an experience which while shocking to many, seems to have paralleled that of other mystics such as the otherdox English Catholic seer Juliana of Norwich, who said: "In the Second Person we have our preservation, in wit and wisdom, as far as our sensuality, our restoring and our saving are concerned. For he is our mother, brother and saviour." [1]

Monatnus claimed to have received a series of direct revelations from the Spirit. He may have claimed to be the paraclete of the Gospel of John 14:16. As they went, "the Three," as they were called, spoke in ecstatic trance-like states and urged their followers to fast and pray, so that they might share these personal revelations. His preachings spread from his native Phrygia, where he reportedly proclaimed the village of Pepuza as the site of the New Jerusalem, across the contemporary Christian world, to Africa and Gaul. The group was generally recognized for its holiness and refused to compromise with Roman authorities on questions of honoring Roman state deities. As a result, it counted many martyrs among its numbers.

The movement was partly inspired by a reading of the Gospel of John— "I will send you the advocate [paraclete], the spirit of truth" (Heine 1987, 1989; Groh 1985). Together with an insistence on ascetic disciple and chastity, this doctrine of continuing revelation represented a challenge teaching authority of the bishops and split the Christian communities. The orthodox hierarchy thus fought to suppress it. Bishop Apollinarius found the church at Ancyra torn in two, and he opposed the "false prophesy" (quoted by Eusebius 5.16.5). Irenaeus, who visited Rome during the height of the controversy, in the pontificate of Eleuterus, returned to find Lyon in dissension, and was inspired to write the first great statement of the mainstream Catholic position, Adversus Haereses.

On the other hand, Tertullian claimed that a the "new prophecy" had been accepted by a bishop of Rome, and that only false accusations had moved him to condemn the movement:

- "For after the Bishop of Rome had acknowledged the prophetic gifts of Montanus, Prisca, and Maximilla, and, in consequence of the acknowledgment, had bestowed his peace on the churches of Asia and Phrygia, he (Praxeas), by importunately urging false accusations against the prophets themselves and their churches... compelled him to recall the pacific letter which he had issued, as well as to desist from his purpose of acknowledging the said gifts. By this Praxeas did a twofold service for the devil at Rome: he drove away prophecy, and he brought in heresy; he put to flight the Paraclete, and he crucified the Father." (Adversus Praxeam, I)

Tertullian was by far the best known defender of Montanists. A respected champion of otherwise orthodox belief, he believed that the new prophecy was genuinely motivated and began to fall out of step with what he began to call "the church of a lot of bishops" (On Modesty).

Although the mainstream Christian church prevailed against Montanism within a few generations, inscriptions in the Tembris valley of northern Phrygia, dated between 249 and 279, openly proclaim their allegiance to Montanism. A letter of Jerome to Marcella, written in 385, refutes the claims of Montanists that had been troubling her [2]. The Montanists reportedly persisted into the eighth century in some regions.

Christian Prophecy before Montanism

Differences between Montanism and Catholicism

The beliefs of Montanism contrasted with mainstream Catholicism in the following ways:

- The belief that the prophecies of the Montanists superseded and fulfilled the doctrines proclaimed by the Apostles.

- The encouragement of ecstatic prophesying and speaking in tongues, contrasting with the more sober and disciplined approach to theology dominant in mainstream Catholicism at the time and since.

- The view that Christians who fell from grace could not be redeemed, also in contrast to the Catholic view that contrition could lead to a sinner's restoration to the church.

- The prophets of Montanism did not speak as messengers of God: "Thus saith the Lord," but rather described themselves as possessed by God, and spoke in his person. "I am the Father, the Word, and the Paraclete," said Montanus (Didymus, De Trinitate, III, xli); This possession by a spirit, which spoke while the prophet was incapable of resisting, is described by the spirit of Montanus: "Behold the man is like a lyre, and I dart like the plectrum. The man sleeps, and I am awake" (Epiphanius, "Hæreses", xlviii, 4).

- A stronger emphasis on the avoidance of sin, church discipline, and apocalyptic living than in mainstream Catholicism. They emphasized chastity, including forbidding remarriage.

Jerome and other church leaders claimed that the Montanists held the belief that the Trinity consisted of only a single person, similar to Sabellianism, but in contrast to the Catholic view that the Trinity is one God of three persons. Other Catholic church leaders and Tertullian denied this charge.

Montanism Ressivisted

John Wesley consider him "one of the holiest men of the second century" Epiphanius —"wretched little man" (page 1) (Christine Tevett, Montanism : Gender, Authority and the New Prophecy. Cambridge University Press; New Ed edition (July 18, 2002) ISBN: 0521528704

Rex D. Butler, The New Prophecy & "New Visions": Evidence of Montanism in the Passion of Perpetua And Felicitas Catholic University of America Press (February 15, 2006)

ISBN: 0813214556

Montanism and proposes that its three authors—Perpetua, Saturus, and the unnamed editor—were Montanists. Although many scholars have discussed both sides of this issue, this work is the most extensive investigation to date.

About the Author Rex D. Butler is adjunct professor at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary.

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Montanists

- Jerome's letter (xli) to Marcella to refute the heresy of Montanus, written in 385, "the passages brought together from the Gospel of John" having occasioned Marcella's questions

- EarlyChurch.org.uk Extensive bibliography and on-line articles.

Sources

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Historia ecclesiae, 5.16–18

Further reading

- Groh, Dennis E. 1985. "Utterance and exegesis: Biblical interpretation in the Montanist crisis," in Groh and Jewett, The Living Text (New York) pp 73 – 95.

- Heine, R.E., 1987 "The Role of the Gospel of John in the Montanist controversy," in Second Century v. 6, pp 1 – 18.

- Heine, R.E., 1989. "The Gospel of John and the Montanist debate at Rome," in Studia Patristica 21, pp 95 – 100.

- Pagels, Elaine, 2003. Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas ISBN 0375501568, contains a brief introduction to Montanism, with notes in chapter "God's Word or Human Words?"

- Trevett, Christine, 1996. Montanism: Gender, Authority and the New Prophecy (Cambridge University Press)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.