Difference between revisions of "Mogao Caves" - New World Encyclopedia

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) (→References: added) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (23 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{images OK}} | + | {{approved}}{{submitted}}{{ready}}{{images OK}}{{copyedited}} |

| + | {{coord|40|02|14|N|94|48|15|E|display=title|region:CN_type:city_source:dewiki}} | ||

{{Infobox World Heritage Site | {{Infobox World Heritage Site | ||

| WHS = Mogao Caves | | WHS = Mogao Caves | ||

| Line 10: | Line 11: | ||

| Session = 11th | | Session = 11th | ||

| Link = http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/440}} | | Link = http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/440}} | ||

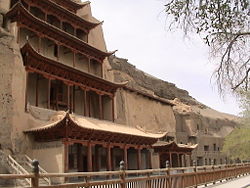

| − | The '''Mogao Caves''' | + | The '''Mogao Caves,''' or '''Mogao Grottoes''' ({{zh-cp|莫高窟|p=mò gāo kū}}) (also known as the '''Caves of the Thousand Buddhas''' and '''Dunhuang Caves'''), forms a system of 492 temples 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) southeast of the center of [[Dunhuang]], an oasis strategically located at a religious and cultural crossroads on the [[Silk Road]], in [[Gansu]] province, [[China]]. The caves contain some of the finest examples of [[Buddhist art]] spanning a period of 1,000 years.<ref name="unesco">UNESCO, [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/440 Mogao Caves.] Retrieved July 21, 2008.</ref> <!-- They are called the '''Qianfodong''' ({{zh-cp|c=千佛洞|p=qiān fó dòng}}) or the '''Dunhuang Caves'''. —>Construction of the Buddhist cave shrines began in 366 C.E., as places to store scriptures and art.<ref>China Page, [http://www.chinapage.com/dunhuang.html Silk Road--DunHuang (Tun-Huang) Grottoes.] Retrieved July 21, 2008.</ref> The Mogao Caves have become the best known of the [[China|Chinese]] Buddhist grottoes and, along with [[Longmen Grottoes]] and [[Yungang Grottoes]], one of the three famous ancient sculptural sites of China. The Mogao Caves became one of the [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Sites]] in 1987.<ref name="unesco"/> |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | As a depository of pivotal [[Buddhist]], [[Taoist]], and [[Christian]] documents, the Mogao Caves provided a rare opportunity for Buddhist monks and devotees to study those doctrines. In that regard, the caves served as a virtual melting pot of Christian, Buddhist, Taoist, and even [[Hindu]] ideas in China. The discovery of the caves that served as a depository of documents from those faiths, sealed from the eleventh century, testify to the interplay of religions. The Diamond Sutra and the Jesus Sutras stand out among the scriptural treasures found in the caves in the twentieth century. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ref> The Mogao Caves have become the best known of the [[China|Chinese]] Buddhist grottoes and, along with [[Longmen Grottoes]] and [[Yungang Grottoes]], one of the three famous ancient sculptural sites of China. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

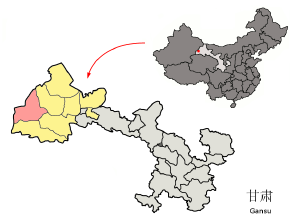

| − | [[Image:Location of Dunhuang within Gansu (China).png|thumb|right|px220| | + | [[Image:Location of Dunhuang within Gansu (China).png|thumb|right|px220|Mogao Caves are in Dunhuang County, Gansu Province, China]] |

| − | According to local legend, in 366 C.E. a [[Buddhist]] monk, Lè Zūn (樂尊), had a vision of a thousand [[Gautama Buddha|Buddhas]] and inspired the excavation of the caves he envisioned. The number of temples eventually grew to more than a thousand.<ref> | + | ===Origins=== |

| − | + | According to local legend, in 366 C.E., a [[Buddhist]] monk, Lè Zūn (樂尊), had a vision of a thousand [[Gautama Buddha|Buddhas]] and inspired the excavation of the caves he envisioned. The number of temples eventually grew to more than a thousand.<ref>Travel China Guide, [http://www.travelchinaguide.com/attraction/gansu/dunhuang/mogao_grottoes/index.htm Dunhuang—Mogao Caves.] Retrieved July 21, 2008.</ref> As Buddhist monks valued austerity in life, they sought retreat in remote caves to further their quest for [[Enlightenment (Buddhism)|enlightenment]]. From the fourth until the fourteenth century, Buddhist monks at Dunhuang collected scriptures from the west while many [[pilgrim]]s passing through the area painted [[mural]]s inside the caves. The cave paintings and architecture served as aids to [[meditation]], as visual representations of the quest for enlightenment, as [[mnemonic]] devices, and as teaching tools to inform illiterate Chinese about Buddhist beliefs and stories. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The murals cover 450,000 square feet (42,000 m²). The caves had been walled off sometime after the | + | The murals cover 450,000 square feet (42,000 m²). The caves had been walled off sometime after the eleventh century after they had become a repository for venerable, damaged and used manuscripts and hallowed paraphernalia.<ref name="idp">International Dunhuang Project, [http://idp.bl.uk/pages/collections_ch.a4d Chinese Exploration and Excavations in Chinese Central Asia.] Retrieved July 21, 2008.</ref> The following, quoted from Fujieda Akira, has been suggested: |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ref> The following, quoted from Fujieda Akira, has been suggested: | ||

| − | <blockquote>The most probable reason for such a huge accumulation of waste is that, when the printing of books became widespread in the tenth century, the handwritten manuscripts of the [[Tripitaka]] at the monastic libraries must have been replaced by books of a new type—the printed Tripitaka. Consequently, the discarded manuscripts found their way to the sacred waste-pile, where torn scrolls from old times as well as the bulk of manuscripts in Tibetan had been stored. All we can say for certain is that he came from the Wu family, because the compound of the three-storied cave temples, Nos. 16-18 and 365-6, is known to have been built and kept by the Wu family, of which the mid-ninth century Bishop of Tun-Huan, Hung-pien, was a member. <ref>Leif Littrup | + | <blockquote>The most probable reason for such a huge accumulation of waste is that, when the printing of books became widespread in the tenth century, the handwritten manuscripts of the [[Tripitaka]] at the monastic libraries must have been replaced by books of a new type—the printed Tripitaka. Consequently, the discarded manuscripts found their way to the sacred waste-pile, where torn scrolls from old times as well as the bulk of manuscripts in Tibetan had been stored. All we can say for certain is that he came from the Wu family, because the compound of the three-storied cave temples, Nos. 16-18 and 365-6, is known to have been built and kept by the Wu family, of which the mid-ninth century Bishop of Tun-Huan, Hung-pien, was a member.<ref>Leif Littrup, ''Analecta Hafniensia: 25 years of East Asian studies in Copenhagen'' (London: Curzon Press, 1998), 112.</ref></blockquote> |

| − | [[Image:Abbotwang.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Abbotwang.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Abbot Wang]] |

| − | In the early 1900s, a Chinese [[Taoist]] named [[Wang Yuanlu]] appointed himself guardian of some of those temples. Wang discovered a walled up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main cave. Behind the wall stood a small cave stuffed with an enormous hoard of manuscripts dating from | + | ===Wang Yuanlu=== |

| + | In the early 1900s, a Chinese [[Taoist]] named [[Wang Yuanlu]] appointed himself guardian of some of those temples. Wang discovered a walled up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main cave. Behind the wall stood a small cave stuffed with an enormous hoard of manuscripts dating from 406 to 1002 C.E. Those included old Chinese [[hemp]] paper scrolls, old [[Tibet]]an scrolls, paintings on hemp, silk or paper, numerous damaged figurines of Buddhas, and other Buddhist paraphernalia. | ||

The subject matter in the scrolls covers diverse material. Along with the expected Buddhist canonical works numbered original commentaries, [[apocrypha]]l works, workbooks, books of prayers, [[Confucian]] works, Taoist works, [[Nestorian Christian]] works, works from the Chinese government, administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries, and calligraphic exercises. The majority of which he sold to [[Aurel Stein]] for the paltry sum of 220 pounds, a deed which made him notorious to this day in the minds of many Chinese. Rumors of that discovery brought several European expeditions to the area by 1910. | The subject matter in the scrolls covers diverse material. Along with the expected Buddhist canonical works numbered original commentaries, [[apocrypha]]l works, workbooks, books of prayers, [[Confucian]] works, Taoist works, [[Nestorian Christian]] works, works from the Chinese government, administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries, and calligraphic exercises. The majority of which he sold to [[Aurel Stein]] for the paltry sum of 220 pounds, a deed which made him notorious to this day in the minds of many Chinese. Rumors of that discovery brought several European expeditions to the area by 1910. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The [[ | + | ===International expeditions=== |

| + | [[Image:Zhang Qian.jpg|thumb|left|220px|The travel of [[Zhang Qian]] to the West, Mogao caves, 618-712 C.E.]] | ||

| + | Those included a joint British/Indian group led by [[Aurel Stein]] (who took hundreds of copies of the [[Diamond Sutra]] because he lacked the ability to read Chinese), a French expedition under [[Paul Pelliot]], a Japanese expedition under [[Otani Kozui]], and a Russian expedition under [[Sergei F. Oldenburg]] which found the least. Pelloit displayed interest in the more unusual and exotic of Wang's manuscripts such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the monastery and associated layman's groups. Those manuscripts survived only because they formed a type of [[palimpsest]] in which the Buddhist texts (the target of the preservation effort) had been written on the opposite side of the paper. | ||

| − | + | The Chinese government ordered the remaining Chinese manuscripts sent to Peking ([[Beijing]]). The mass of Tibetan manuscripts remained at the sites. Wang embarked on an ambitious refurbishment of the temples, funded in part by solicited donations from neighboring towns and in part by donations from Stein and Pelliot.<ref name="idp"/> The image of the [[Chinese astronomy]] [[Dunhuang map]] is one of the many important artifact found on the scrolls. Today, the site continues the subject of an ongoing archaeological project.<ref>International Dunhuang Project, [http://idp.bl.uk/ Homepage.] Retrieved July 21, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | < | ||

==Gallery== | ==Gallery== | ||

| Line 117: | Line 41: | ||

Image:TsangMonk.jpg|A painting of Xuanzang performing ceremonies for the Buddha | Image:TsangMonk.jpg|A painting of Xuanzang performing ceremonies for the Buddha | ||

Image:Trade_in_silkroad.jpg|Trade on the Silk Road | Image:Trade_in_silkroad.jpg|Trade on the Silk Road | ||

| − | Image:HanWudiBuddhas.jpg|A close-up of the fresco describing Emperor [[Han Wudi]] ( | + | Image:HanWudiBuddhas.jpg|A close-up of the fresco describing Emperor [[Han Wudi]] (156–87 B.C.E.) worshiping two statues of the [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]], c. 700 C.E. |

<!--Image:20060424065650.jpg—> | <!--Image:20060424065650.jpg—> | ||

Image:DunhuangCave323.jpg|A complete view of the painting. | Image:DunhuangCave323.jpg|A complete view of the painting. | ||

| Line 132: | Line 56: | ||

*[[Tao-te Ching]] | *[[Tao-te Ching]] | ||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * Akira, Fujieda, "The Tun-Huan Manuscripts." In Donald Leslie, Colin Mackerras, Gungwu Wang, and C. P. Fitzgerald. 1973. ''Essays on the Sources for Chinese History''. Canberra: Australian National University Press. ISBN 9780708103982. | ||

| + | * Baumer, Christoph. 2006. ''The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity''. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845111151. | ||

| + | * Hopkirk, Peter. 1980. ''Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia''. London: Murray. ISBN 9780719537387. | ||

| + | * Littrup, Leif. 1988. ''Analecta Hafniensia: 25 Years of East Asian Studies in Copenhagen.'' London: Curzon Press. ISBN 9780700701995. | ||

| + | * Moule, A. C. 1930. ''Christians in China Before the Year 1550''. London: S.P.C.K. OCLC 181797710. | ||

| + | * Mu, Soeng. 2000. ''Diamond Sutra: Transforming the Way We Perceive the World''. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861711604. | ||

| + | * Nhat Hanh, Thich. 1992. ''The Diamond that Cuts Through Illusion: Commentaries on the Prajñaparamita Diamond Sutra''. Berkeley, Calif: Parallax Press. ISBN 9780938077510. | ||

| + | * Palmer, Martin, and Eva Wong. 2001. ''The Jesus Sutras: Rediscovering the Lost Scrolls of Taoist Christianity''. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 9780345434241. | ||

| + | * Riegert, Ray, and Thomas Moore. 2003. ''The Lost Sutras of Jesus: Unlocking the Ancient Wisdom of the Xian Christian Monks''. Berkeley, Calif: Seastone. ISBN 9781569753606. | ||

| + | * Saeki, P. Yoshio. 1951. ''Nestorian Documents and Relics in China''. Tokyo: Maruzen. OCLC 52011545. | ||

| + | * Tang, Li. 2004. ''A Study of the History of Nestorian Christianity in China and its Literature in Chinese''. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631522745. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 9, 2022. | |

| − | * [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/440 UNESCO Mogao Caves Site] | + | * [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/440 UNESCO Mogao Caves Site]. |

| − | + | * [http://idp.bl.uk/ International Dunhuang Project]. | |

| − | * [http://idp.bl.uk/ International Dunhuang Project] | + | * [http://www.diamondsutra.us Core Teachings of Diamond Sutra with visual art by Fernando Casas]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http://www.diamondsutra.us Core Teachings of Diamond Sutra with visual art by Fernando Casas] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{World Heritage Sites in China}} | {{World Heritage Sites in China}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Sites of religious pilgrimages]] | [[Category:Sites of religious pilgrimages]] | ||

| − | [[Category:World Heritage | + | [[Category:World Heritage Site]] |

[[Category:Art]] | [[Category:Art]] | ||

[[Category:Buddhism]] | [[Category:Buddhism]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:28, 9 November 2022

Coordinates:

| Mogao Caves* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, v, vi |

| Reference | 440 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

The Mogao Caves, or Mogao Grottoes (Chinese: 莫高窟; pinyin: mò gāo kū) (also known as the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas and Dunhuang Caves), forms a system of 492 temples 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) southeast of the center of Dunhuang, an oasis strategically located at a religious and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, in Gansu province, China. The caves contain some of the finest examples of Buddhist art spanning a period of 1,000 years.[1] Construction of the Buddhist cave shrines began in 366 C.E., as places to store scriptures and art.[2] The Mogao Caves have become the best known of the Chinese Buddhist grottoes and, along with Longmen Grottoes and Yungang Grottoes, one of the three famous ancient sculptural sites of China. The Mogao Caves became one of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1987.[1]

As a depository of pivotal Buddhist, Taoist, and Christian documents, the Mogao Caves provided a rare opportunity for Buddhist monks and devotees to study those doctrines. In that regard, the caves served as a virtual melting pot of Christian, Buddhist, Taoist, and even Hindu ideas in China. The discovery of the caves that served as a depository of documents from those faiths, sealed from the eleventh century, testify to the interplay of religions. The Diamond Sutra and the Jesus Sutras stand out among the scriptural treasures found in the caves in the twentieth century.

History

Origins

According to local legend, in 366 C.E., a Buddhist monk, Lè Zūn (樂尊), had a vision of a thousand Buddhas and inspired the excavation of the caves he envisioned. The number of temples eventually grew to more than a thousand.[3] As Buddhist monks valued austerity in life, they sought retreat in remote caves to further their quest for enlightenment. From the fourth until the fourteenth century, Buddhist monks at Dunhuang collected scriptures from the west while many pilgrims passing through the area painted murals inside the caves. The cave paintings and architecture served as aids to meditation, as visual representations of the quest for enlightenment, as mnemonic devices, and as teaching tools to inform illiterate Chinese about Buddhist beliefs and stories.

The murals cover 450,000 square feet (42,000 m²). The caves had been walled off sometime after the eleventh century after they had become a repository for venerable, damaged and used manuscripts and hallowed paraphernalia.[4] The following, quoted from Fujieda Akira, has been suggested:

The most probable reason for such a huge accumulation of waste is that, when the printing of books became widespread in the tenth century, the handwritten manuscripts of the Tripitaka at the monastic libraries must have been replaced by books of a new type—the printed Tripitaka. Consequently, the discarded manuscripts found their way to the sacred waste-pile, where torn scrolls from old times as well as the bulk of manuscripts in Tibetan had been stored. All we can say for certain is that he came from the Wu family, because the compound of the three-storied cave temples, Nos. 16-18 and 365-6, is known to have been built and kept by the Wu family, of which the mid-ninth century Bishop of Tun-Huan, Hung-pien, was a member.[5]

Wang Yuanlu

In the early 1900s, a Chinese Taoist named Wang Yuanlu appointed himself guardian of some of those temples. Wang discovered a walled up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main cave. Behind the wall stood a small cave stuffed with an enormous hoard of manuscripts dating from 406 to 1002 C.E. Those included old Chinese hemp paper scrolls, old Tibetan scrolls, paintings on hemp, silk or paper, numerous damaged figurines of Buddhas, and other Buddhist paraphernalia.

The subject matter in the scrolls covers diverse material. Along with the expected Buddhist canonical works numbered original commentaries, apocryphal works, workbooks, books of prayers, Confucian works, Taoist works, Nestorian Christian works, works from the Chinese government, administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries, and calligraphic exercises. The majority of which he sold to Aurel Stein for the paltry sum of 220 pounds, a deed which made him notorious to this day in the minds of many Chinese. Rumors of that discovery brought several European expeditions to the area by 1910.

International expeditions

Those included a joint British/Indian group led by Aurel Stein (who took hundreds of copies of the Diamond Sutra because he lacked the ability to read Chinese), a French expedition under Paul Pelliot, a Japanese expedition under Otani Kozui, and a Russian expedition under Sergei F. Oldenburg which found the least. Pelloit displayed interest in the more unusual and exotic of Wang's manuscripts such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the monastery and associated layman's groups. Those manuscripts survived only because they formed a type of palimpsest in which the Buddhist texts (the target of the preservation effort) had been written on the opposite side of the paper.

The Chinese government ordered the remaining Chinese manuscripts sent to Peking (Beijing). The mass of Tibetan manuscripts remained at the sites. Wang embarked on an ambitious refurbishment of the temples, funded in part by solicited donations from neighboring towns and in part by donations from Stein and Pelliot.[4] The image of the Chinese astronomy Dunhuang map is one of the many important artifact found on the scrolls. Today, the site continues the subject of an ongoing archaeological project.[6]

Gallery

A close-up of the fresco describing Emperor Han Wudi (156–87 B.C.E.) worshiping two statues of the Buddha, c. 700 C.E.

See also

- Chinese Buddhism

- Gansu

- Wood Block Printing

- Silk Road

- Han Dynasty

- Buddhist Art

- Tao-te Ching

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 UNESCO, Mogao Caves. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ↑ China Page, Silk Road—DunHuang (Tun-Huang) Grottoes. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ↑ Travel China Guide, Dunhuang—Mogao Caves. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 International Dunhuang Project, Chinese Exploration and Excavations in Chinese Central Asia. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ↑ Leif Littrup, Analecta Hafniensia: 25 years of East Asian studies in Copenhagen (London: Curzon Press, 1998), 112.

- ↑ International Dunhuang Project, Homepage. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Akira, Fujieda, "The Tun-Huan Manuscripts." In Donald Leslie, Colin Mackerras, Gungwu Wang, and C. P. Fitzgerald. 1973. Essays on the Sources for Chinese History. Canberra: Australian National University Press. ISBN 9780708103982.

- Baumer, Christoph. 2006. The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845111151.

- Hopkirk, Peter. 1980. Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. London: Murray. ISBN 9780719537387.

- Littrup, Leif. 1988. Analecta Hafniensia: 25 Years of East Asian Studies in Copenhagen. London: Curzon Press. ISBN 9780700701995.

- Moule, A. C. 1930. Christians in China Before the Year 1550. London: S.P.C.K. OCLC 181797710.

- Mu, Soeng. 2000. Diamond Sutra: Transforming the Way We Perceive the World. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861711604.

- Nhat Hanh, Thich. 1992. The Diamond that Cuts Through Illusion: Commentaries on the Prajñaparamita Diamond Sutra. Berkeley, Calif: Parallax Press. ISBN 9780938077510.

- Palmer, Martin, and Eva Wong. 2001. The Jesus Sutras: Rediscovering the Lost Scrolls of Taoist Christianity. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 9780345434241.

- Riegert, Ray, and Thomas Moore. 2003. The Lost Sutras of Jesus: Unlocking the Ancient Wisdom of the Xian Christian Monks. Berkeley, Calif: Seastone. ISBN 9781569753606.

- Saeki, P. Yoshio. 1951. Nestorian Documents and Relics in China. Tokyo: Maruzen. OCLC 52011545.

- Tang, Li. 2004. A Study of the History of Nestorian Christianity in China and its Literature in Chinese. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631522745.

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- UNESCO Mogao Caves Site.

- International Dunhuang Project.

- Core Teachings of Diamond Sutra with visual art by Fernando Casas.

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.