Microcosm and Macrocosm

Macrocosm/microcosm is a Greek compound of μακρο- "Macro-" and μικρο- "Micro-", which are Greek respectively for "large" and "small", and the word κόσμος kósmos which means "order" as well as "world" or "ordered world".

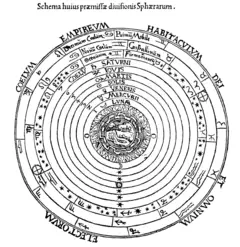

The paired concept of Macrocosm and Microcosm is an idea that there is a corresponding similarity in pattern or nature or structure between human being and the universe. Some recognize active relationships between man and the universe based upon the idea of the similarity. The concept of macrocosm/microcosm views man as a small universe and the universe as anthropomorphic existence. This concept is found from the ancient thought to renaissance as well as in Buddhism and Upanishads, perhaps in other wider religious traditions. Similar concepts were held by hermetic philosophers like Paracelsus, and by Baruch Spinoza, Leibnitz and later by Friedrich Schelling (1775-1854).

This idea, however, generally declined after seventeenth century along with the development of modern science. After modern times, this idea was mainly preserved in the realm of literature such as Novalis (1772 - 1801), a German romanticist poet, and Baudelaire (1821 – 1867), a French poet, as well as by some philosophers above.

Ancient thought

In its most general sense, a cosmos is an orderly or harmonious system. It originates from a Greek term κόσμος meaning "order, orderly arrangement, ornaments," and is the antithetical concept of chaos. Today the word is generally used as synonym of the word 'universe' (considered in its orderly aspect). The word cosmetics originates from the same root.

The idea of the correspondence or some continuity between the cosmos and human being is found in Pythagoras in an incipient form. He, however, did not use the terminology of microcoms/macrocosm and did not have a clear anthropomorphic view of the cosmos.

Pythagoras is said to have been the first philosopher to apply the term "cosmos" to the Universe, perhaps from application to the starry firmament. The term so used is parallel to the Zoroastrian term aša, the concept of a divine order, or divinely ordered creation. Cosmos, thus, means not only the totality of the universe but it implies that the universe is ordered by the principle of harmony and balance. Pythagoras conceived the number or numerical ratio as the universal principle of harmony and understood that human aesthetic experience in music and art is closed tied to the orderly movement of stars. His understanding of the correspondence between the cosmos and man gave a framework of thought within which religious rituals, studies of mathematics and astronomy, and artistic activities are closed tied. Pythagoras and his religious sect offered solutions of mathematical questions to the divine and conceived mathematical exercises as religious practices to purify the soul.

Although Plato did not use the terminology, a clearer concept of macrocosm/microcosm is found in his Timaeus. He wrote on the idea of the soul of cosmos in its anthropomorphic representation:

Therefore, we may consequently state that: this world is indeed a living being endowed with a soul and intelligence ... a single visible living entity containing all other living entities, which by their nature are all related.

Plato, Timaeus, 29/30; 4th century B.C.E.

Neo-Platonism: Plotinus

Neo-Platonist Plotinus developed a clearer concept of "world-soul" ("Anima mundi" in Latin) based upon Plato's ideas in Timaeus. Plato had a concept of "demiurge" (from the Greek δημιουργός dēmiourgós, Latinized demiurgus, meaning "artisan" or "craftsman", literally "worker in the service of the people", from δήμιος "of the people" + ἔργον "work"), a creative deity, who designed and made the cosmos.

designer of the cosmos,

Plotinus offers an alternative to the orthodox Christian notion of creation ex nihilo (out of nothing), which attributes to God the deliberation of mind and action of a will, although Plotinus never mentions Christianity in any of his works. Emanation ex deo (out of God), confirms the absolute transcendence of the One, making the unfolding of the cosmos purely a consequence of its existence; the One is in no way affected or diminished by these emanations. Though the emanations are, since as they become farther away from the source they became diminished. Plotinus uses the analogy of the Sun which emanates light indiscriminately without thereby diminishing itself, or reflection in a mirror which in no way diminishes or otherwise alters the object being reflected.

The first emanation is nous (thought), identified metaphorically with the demiurge in Plato's Timaeus. It is the first will towards Good. From nous proceeds the world soul, which Plotinus subdivides into upper and lower, identifying the lower aspect of Soul with nature. From the world soul proceeds individual human souls, and finally, matter, at the lowest level of being and thus the least perfected level of the cosmos. Despite this relatively pedestrian assessment of the material world, Plotinus asserted the ultimately divine nature of material creation since it ultimately derives from the One, through the mediums of nous and the world soul. It is by the Good or through beauty that we recognize the One, in material things and then in the Forms.[1]

The essentially devotional nature of Plotinus' philosophy may be further illustrated by his concept of attaining ecstatic union with the One (henosis see Iamblichus). Porphyry relates that Plotinus attained such a union four times during the years he knew him. This may be related to enlightenment, liberation, and other concepts of mystical union common to many Eastern and Western traditions. Some have compared Plotinus' teachings to the Hindu school of Advaita Vedanta (advaita "not two", or "non-dual"),[2].

It also permeated the thinking of Hermetic philosophers and alchemists.

Medieval and modern thought

Throughout the Middle Ages the Macrocosmic quaternities of the elements and the seasons were linked to the Microcosmic quaternities of the four humours and ages of Man. The macrocosm/microcosm schema was developed further by the Swiss physician and alchemist Paracelsus, who proposed that within man was an inner heaven with stars. Paracelsus's philosophy of correspondences was based upon the belief that for every ailment and illness in Man (the microcosm) there existed a cure in nature (the macrocosm).

The English physician and alchemist Robert Fludd (1574-1637) expicitly based his work Utriusque Cosmi Historia (The history of the two worlds) upon the macro/micro correspondence; as does Sir Thomas Browne in his binary Discourses of 1658: Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial depicts the small, temporal world of man, whilst The Garden of Cyrus represents the macrocosm, in which the ubiquitous and eternal quincunx pattern is discerned in art, nature and the Cosmos.

The great enigma of alchemy is the mystery between the macrocosm and microcosm. Equally an unsolved enigma of English literature is the relationship between Browne's diptych Discourses: the microcosm world of Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial and the macrocosm world of The Garden of Cyrus.

See Also

- Family as a model for the state

- Golden Mean

- Surat Shabda Yoga

- Rose Cross and Alchemy

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Republic, Plato, trans. By B. Jowett M.A., Vintage Books, NY. § 435, pg 151

Bibliography

- Theories of Macrocosms and Microcosms in the History of Philosophy, G. P. Conger, NY, l922, which includes a survey of critical discussions up to l922.

External Links

de:Mikrokosmos

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Microcosm_and_Macrocosm history

- Cosmos history

- Anima_mundi_(spirit) history

- Plotinus history

- Demiurge history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ I.6.6 and I.6.9

- ↑ This connection is made in the works of Ananda Coomaraswamy[1] and has been elaborated upon in J. F. Staal, Advaita and Neoplatonism: A critical study in comparative philosophy, Madras: University of Madras, 1961. More recently, see Frederick Copleston, Religion and the One: Philosophies East and West (University of Aberdeen Gifford Lectures 1979-1980) and the special section "Fra Oriente e Occidente" in Annuario filosofico No. 6 (1990), including the articles "Plotino e l'India" by Aldo Magris and "L'India e Plotino" by Mario Piantelli. The connection is also mentioned in Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (ed.), History of Philosophy Eastern and Western (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1952), vol. 2, p. 114; in a lecture by Professor Gwen Griffith-Dickson [2]; and in John Y. Fenton, "Mystical Experience as a Bridge for Cross-Cultural Philosophy of Religion: A Critique," Journal of the American Academy of Religion 1981, p. 55. The joint influence of Advaitin and Neoplatonic ideas on Ralph Waldo Emerson is considered in Dale Riepe, "Emerson and Indian Philosophy," Journal of the History of Ideas, 1967.