Measures of national income and output

Measures of national income and output are used in economics to estimate the welfare of an economy by totaling the value of goods and services produced in an economy. National economies have been using systems of national accounting first developed by Simon Kuznets in the 1940s and 1960s. Some of the more common measures are Gross National Product (GNP), Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Net National Product (NNP), and Net National Income (NNI).

Overview

There are several different ways of calculating the measures of national income and output.

- The expenditure approach determines aggregate demand, or Gross National Expenditure, by summing consumption, investment, government expenditure, and net exports.

- On the other hand, the income approach and the closely related output approach, can been seen as the summation of consumption, savings, and taxation.

The three methods must yield the same results because the total expenditures on goods and services (GNE) must by definition be equal to the value of the goods and services produced (GNP) which must be equal to the total income paid to the factors that produced these goods and services (GNI).

Thus, GNP = GNI = GNE by definition.

However, in practice minor differences are obtained from the various methods due to changes in inventory levels. This is because goods in inventory have been produced (therefore included in GNP), but not yet sold (therefore not yet included in GNE). Similar timing issues can also cause a slight discrepancy between the value of goods produced (GNP) and the payments to the factors that produced the goods, particularly if inputs are purchased on credit, and also because wages are collected often after a period of production.

In the following calculations, "Gross" means that depreciation of capital stock is not subtracted from the total value. If net investment (which is gross investment minus depreciation) is substituted for gross investment in equations below, then the formula for net domestic product is obtained. Consumption and investment in this equation are expenditure on final goods and services. The exports-minus-imports part of the equation (often called "net exports") adjusts this by subtracting the part of this expenditure not produced domestically (the imports), and adding back in domestic area (the exports).

Gross National Product

Gross National Product (GNP) is the total value of final goods and services produced in a year by domestically owned factors of production. Final goods are goods that are ultimately consumed rather than used in the production of another good.

EXAMPLE: A car sold to a consumer is a final good; the components such as tires sold to the car manufacturer are not; they are intermediate goods used to make the final good. The same tires, if sold to a consumer, would be a final good. Only final goods are included when measuring national income. If intermediate goods were included too, this would lead to double counting; for example, the value of the tires would be counted once when they are sold to the car manufacturer, and again when the car is sold to the consumer.

NOTE: Only newly produced goods are counted. Transactions in existing goods, such as second-hand cars, are not included, as these do not involve the production of new goods.

Income is counted as part of GNP according to who owns the factors of production rather than where the production takes place.

EXAMPLE : In the case of a German-owned car factory operating in the US, the profits from the factory would be counted as part of German GNP rather than US GNP because the capital used in production (the factory, machinery, etc.) is German owned. The wages of the American workers would be part of US GNP, while wages of any German workers on the site would be part of German GNP.

Real and nominal values

Nominal GNP measures the value of output during a given year using the prices prevailing during that year. Over time, the general level of prices rise due to inflation, leading to an increase in nominal GNP even if the volume of goods and services produced is unchanged.

Real GNP measures the value of output in two or more different years by valuing the goods and services produced at the same prices. For example, GNP might be calculated for 2000, 2001 and 2002 using the prices prevailing in 2002 for all of the calculations. This gives a measure of national income which is not distorted by inflation.

Depreciation and Net National Product

Not all GNP data show the production of final goods and services—part represents output that is set aside to maintain the nation's productive capacity. Capital goods, such as buildings and machinery, lose value over time due to wear and tear and obsolescence.

Depreciation (also known as consumption of fixed capital) measures the amount of GNP that must be spent on new capital goods to maintain the existing physical capital stock.

NOTE: Depreciation measures the amount of GNP that must be spent on new capital goods to offset this effect.

Net National Product (NNP) is the total market value of all final goods and services produced by citizens of an economy during a given period of time (Gross National Product or GNP) minus depreciation. Net National Product can be similarly applied at a country's domestic output level.

NNP is the amount of goods in a given year which can be consumed without reducing the amount which can be consumed in the future. Setting part of NNP aside for investment permits the growth of the capital stock and the consumption of more goods in the future.

NNP can also be expressed as total compensation of employees + net indirect tax paid on current production + operating surplus.

Hence, through the income approach we define:

- Net National Product (NNP) is GNP minus depreciation.

- Net National Income (NNI) is NNP minus indirect taxes.

- Personal Income (PI) is NNI minus retained earnings, corporate taxes, transfer payments, and interest on the public debt.

- Personal Disposable Income (PDI) is PI minus personal taxes, plus transfer payments.

Then, in summary, we have:

- Personal savings (S) plus personal consumption (C) = personal disposable income (PDI).

- PDI plus personal taxes paid minus transfer payments received = personal income (PI).

- PI plus retained earnings plus corporate taxes plus transfer payments plus interest on the public debt = net national income (NNI).

- NNI plus indirect taxes = net national product (NNP).

- NNP plus depreciation = gross national product (GNP).

Gross Domestic Product

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the total value of final goods and services produced within a country's borders in a year. GDP counts income according to where it is earned rather than who owns the factors of production.

EXAMPLE: In the above case of a German-owned car factory operating in the US, all of the income from the car factory would be counted as US GDP rather than German GDP.

Measuring GDP

There are two ways to measure GDP. The most common approach to measuring and understanding GDP is the expenditure method. The other is the income method.

- Expenditure method

Measured according to the expenditure method, GDP is equal to consumption + investment + government expenditures + exports - imports, which can be written as

- GDP = C + I + G + NX

where:

- C = Consumption

- I = Investments

- G = Government spending

- NX = net exports (exports minus imports)

Example 1: If you spend money to renovate your hotel so that occupancy rates increase, that is private investment, but if you buy shares in a consortium to do the same thing it is saving. The former is included when measuring GDP (in I), the latter is not. However, when the consortium conducted its own expenditure on renovation, that expenditure would be included in GDP.

Example 2: If a hotel is a private home then renovation spending would be measured as Consumption, but if a government agency is converting the hotel into an office for civil servants the renovation spending would be measured as part of public sector spending (G).

Example 3: If the renovation involves the purchase of a chandelier from abroad, that spending would also be counted as an increase in imports, so that NX would fall and the total GDP is affected by the purchase. (This highlights the fact that GDP is intended to measure domestic production rather than total consumption or spending. Spending is really a convenient means of estimating production.)

Example 4: If a domestic producer is paid to make the chandelier for a foreign hotel, the situation would be reversed, and the payment would be counted in NX (positively, as an export). Again, GDP is attempting to measure production through the means of expenditure; if the chandelier produced had been bought domestically it would have been included in the GDP figures (in C or I) when purchased by a consumer or a business, but because it was exported it is necessary to "correct" the amount consumed domestically to give the amount produced domestically.

- Income method

The income approach focuses on finding the total output of a nation by finding the total income of a nation. This is acceptable, because all money spent on the production of a good—the total value of the good—is paid to workers as income.

The main types of income that are included in this measurement are rent (the money paid to owners of land), salaries and wages (the money paid to workers who are involved in the production process, and those who provide the natural resources), interest (the money paid for the use of man-made resources, such as machines used in production), and profit (the money gained by the entrepreneur—the businessman who combines these resources to produce a good or service).

In this income approach, GDP(I) is equal to Net Domestic Income (NDI at factor cost) + indirect taxes + depreciation – subsidy, where Net Domestic Income (NDI) is the sum of returns of factors of production in the society. Thus,

- Net Domestic Income (NDI) = compensation of employees + net interest (credit – debit) + corporate profits (distributed + undistributed) + proprietor’s income (self-employed + small business) + rental income.

The difference between basic prices and final prices (those used in the expenditure calculation) is the total taxes and subsidies that the Government has levied or paid on that production. So adding taxes less subsidies on production and imports converts GDP at factor cost to GDP(I) in the above equation.

Doublecounting in GDP

EXAMPLE: The intermediate goods selling prices for a book (sold in a bookstore) are as follows: A tree company sells to a paper mill wood for $1; the paper mill sells paper to a textbook publisher for $3; the publisher sells the textbook to a bookstore for $7 and the bookstore sells the textbook for $75. Although the sum of all intermediate prices plus the selling price of the book comes to $86, we add to GDP only the final selling price $75. The price of the "tree," "paper," and book is included in the final selling price of the book by the bookstore. To include these amounts in GDP calculation would be to "double count."

Net Domestic Product

Net Domestic Product (NDP) is the equivalent application of NNP. Thus, NDP is equal to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) minus depreciation: Net domestic product (NDP) equals the gross domestic product (GDP) minus depreciation on a country's capital goods.

- NDP = GDP – Depreciation

NDP is an estimate of how much the country has to spend to maintain the current GDP. If the country is not able to replace the capital stock lost through depreciation, then GDP will fall. In addition, a growing gap between GDP and NDP indicates increasing obsolescence of capital goods, while a narrowing gap would mean that the condition of capital stock in the country is improving.

Gross National Income

Gross national income (GNI) is GDP less net taxes on production and imports, less compensation of employees and property income payable to the rest of the world plus the corresponding items receivable from the rest of the world. It includes wages, rents, interest, and profits, not only in the form of cash payments, but as income from contributions made by employers to pension funds, income of the self-employed, and undistributed business profits.

In other words, Gross national income (GNI) is GDP less primary incomes payable to non-resident units plus primary incomes receivable from non-resident units. From this point of view, GNP is the better indicator of a country’s economic trend.

However, calculating the real GDP growth allows economists to determine if production increased or decreased, regardless of changes in the purchasing power of the currency.

An alternative approach to measuring GNI at market prices is as the aggregate value of the balances of gross primary incomes for all sectors.

NOTE: GNI is identical to gross national product (GNP) as, generally, used previously in national accounts and we may formulate basic principle of fundamental national accounting:

- The value of total output equals the value of total income

This makes another very important point:

Real income cannot be increased without producing more, redistributing income does nothing to increase the amount of wealth available at any point in time (Mings and Marlin 2000).

Net National Income

Net National Income (NNI) can be defined as the Net National Product (NNP) minus indirect taxes. Net National Income encompasses the income of households, businesses, and the government. It can be expressed as:

- NNI = C + I + G + (NX) + net foreign factor income - indirect taxes - depreciation

Where again:

- C = Consumption

- I = Investments

- G = Government spending

- NX = net exports (exports minus imports)

GDP vs. GNP

To convert from GDP to GNP you must add factor input payments to foreigners that correspond to goods and services produced in the domestic country using the factor inputs supplied by foreigners.

To convert from GNP to GDP you must subtract factor income receipts from foreigners that correspond to goods and services produced abroad using factor inputs supplied by domestic sources.

NOTE: GDP is a better measure of the state of production in the short term. GNP is a better when analysing sources and uses of income on a longer term basis.

Relationship to welfare

GNP

GNP per person is often used as a measure of people's welfare. Countries with higher GNP often score highly on other measures of welfare, such as life expectancy. However, there are serious limitations to the usefulness of GNP as a measure of welfare:

- Measures of GNP typically exclude unpaid economic activity, most importantly domestic work such as childcare. This can lead to distortions; for example, a paid childminder's income will contribute to GNP, whereas an unpaid mother's time spent caring for her children will not, even though they are both carrying out the same activity.

- GNP takes no account of the inputs used to produce the output. For example, if everyone worked for twice the number of hours, then GNP might roughly double, but this does not necessarily mean that workers are better off as they would have less leisure time. Similarly, the impact of economic activity on the environment is not directly taken into account in calculating GNP.

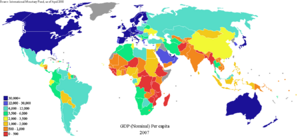

- Comparison of GNP from one country to another may be distorted by movements in exchange rates. Measuring national income at purchasing power parity (PPP) can help to overcome this problem. The PPP theory uses the long-term equilibrium exchange rate of two currencies to equalize their purchasing power. Developed by Gustav Cassel in 1920, it is based on the law of one price which states that, in an ideally efficient market, identical goods should have only one price.

GDP

Simon Kuznets, the inventor of the GDP, had this to say in his very first report to the US Congress in 1934:

...the welfare of a nation [can] scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income...(Kuznets 1934)

In 1962, Kuznets stated:

Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between costs and returns, and between the short and long run. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what and for what (Kuznets 1962).

Kuznets’ own uncertainty about GDP being a good measure of national welfare is well founded.The standard of living is a measure of economic welfare. It generally refers to the availability of scarce goods and services, usually measured by per capita income or per capita consumption, calculated in constant dollars, to satisfy wants rather than needs.

Because the well-being that living standards are supposed to measure is an individual matter, per capita availability of goods and services in a country is a measure of general welfare only if the goods and services are distributed fairly evenly among people. Besides, just as Kuznets hinted, improvement in standard of living can result from improvements in economic factors such as productivity or per capita real economic growth, income distribution and availability of public services, and non-economic factors, such as protection against unsafe working conditions, clean environment, low crime rate, and so forth.

Advantage

All these items notwithstanding, GDP per capita is often used as an indicator of standard of living in an economy, the rationale being that all citizens benefit from their country's increased economic production.

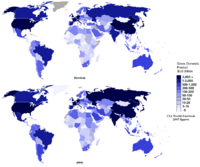

The major advantages to using GDP per capita as an indicator of standard of living are that it is measured frequently, widely, and consistently; frequently in that most countries provide information on GDP on a quarterly basis (which allows trends to be spotted quickly), widely in that some measure of GDP is available for practically every country in the world (allowing crude comparisons between the standard of living in different countries), and consistently in that the technical definitions used within GDP are relatively consistent between countries (so there can be confidence that the same thing is being measured in each country).

Disadvantage

The major disadvantage of using GDP as an indicator of standard of living is that it is not, strictly speaking, a measure of standard of living, which can be generally defined as "the quality and quantity of goods and services available to people, and the way these goods and services are distributed within a population."

GDP does not distinguish between consumer and capital goods; it does not take income distribution into account; it does not take account of differences in the economic goods and services that are not measured in GDP at all; it is subject to the vagaries of translating income measures into a common currency and it fails to take into account differences of tastes among nations.

Critique by Austrian economists

Austrian economists are critical of the basic idea of attempting to quantify national output. Frank Shostak (2001) quotes Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises:

The attempt to determine in money the wealth of a nation or the whole mankind are as childish as the mystic efforts to solve the riddles of the universe by worrying about the dimension of the pyramid of Cheops.

Shostak elaborated in his own criticism:

The GDP framework cannot tell us whether final goods and services that were produced during a particular period of time are a reflection of real wealth expansion, or a reflection of capital consumption. ... For instance, if a government embarks on the building of a pyramid, which adds absolutely nothing to the well-being of individuals, the GDP framework will regard this as economic growth. In reality, however, the building of the pyramid will divert real funding from wealth-generating activities, thereby stifling the production of wealth (Shostak 2001).

Conclusion

Various national accounting formulas for GDP, GNP, and GNI may now be summarized here:

- GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

- GNP = C + I + G + (X - M) + NR

- GNI = C + I + G + (X - M) + NR - CC – IBT.

where C = Personal consumption expenditures;

- I = Gross private domestic investment;

- G = Government consumption expenditures;

- X = Net exports of goods and services;

- M = Net imports of goods and services;

- NR = Net income from assets abroad;

- CC = Consumption of fixed capital;

- IBT = Indirect business taxes

However, as soon as these strictly economic statistics (GNP, GDP) start aspiring to capture the well-being or standard of living trends and their mapping in any particular country, those claims will be absolutely false.

There are two reasons why these economic statistics cannot tell anything at all about the well-being of the society even if taken onto per capita basis. True, we can infer that if GDP (or GNP) per capita series in constant dollars grows within the short period of years, the living standard may increase as well; but that is all we can say. As the Austrian economist Frank Shostak stated, mentioned above, if any government starts building pyramids, GDP will be growing, yet—as the pyramids have no use for anybody—the standard of living will not (Shostak 2001). (Shostak 2001)

The other reason is that we cannot compare with or statistically infer anything from the two or more environments that are absolutely independent on each other. One is the economy and the other is sociology combined with psychology.

Example 1: Imagine an oil-rich developing country where all the monetary growth (mapped by GDP, GNP per capita, and so forth) goes to a ruling clique and virtually nothing to the rest of the society. There, unless the income distribution (from the oil) is just, the weighted average (median as opposed to mean) of GDP/per capita will at the best be constant, most of the society’s expectations, dreams of a better life are shattered and the coefficient of “well-being” (which is based on “feeling good”) will actually be decreasing.

Example 2: In Eastern Europe under the Communist regimes everybody, with the exception of a few elites, was equally poor (no matter what job they did), yet the mood, and to large extent even their expression of being content with the situation, and morality (though not necessarily ethics) were quite high. However, once the “democratic” turnaround, propelled by the old Communist constitution, gave rise to the new class of nouveau riche (namely old Communist apparatchiks who simply stole the state property, because there was nothing in the constitution to prevent them) the rest of society, still poor as before, experienced a drastic downturn of “mood” and thus, sense of “well-being,” even though the GDP and such measures kept rising. This can be explained by the fact that the income distribution (mapped by the Ginni Index) showed incredibly high social stratification which, in Europe, historically has led to society's doldrums (Karasek 2005).

Nevertheless, even in the strictly economic sphere, these measures of national income and output can serve their purpose—comparing economic trends within its own country’s history, or with other countries’ trends; provide short-term forecasting, and so forth—only under specific conditions. These conditions require the following:

- Keep the definition of each of the statistical characteristics (measures) constant over a long period of time (ideal would be not to change it at all throughout the society’s history). With regards to comparison with other countries, the problem of considerably different basic definitions, due to political or other “societal” considerations, should be looked for. Hence:

Using Marxist principles, those countries sometime exclude from aggregate output the value of wide ranges of services, such as government administration and transportation. Attention is instead concentrated on output of goods. The exclusion understate GNP and influence planning, which tend to neglect transport, distribution and services. Aggregate growth rates are overstated since productivity increases more rapidly in the (counter) goods-producing sectors than in neglected service sectors (Herick-Kindleberger 1983).

- In analysis of historical trends, comparisons with other country’s trends and, above all, modeling and forecasts, work only with constant data series. That means to leave inflation or deflation out of all the data-series (Karasek 1988: 36, 73-74, 82).

- Still a significant problem remains as the question of comparison of the standards of living among several countries comes up. Even though we have the above defined characteristics, such as Personal Disposable Income (PDI) computed for an individual country’s currency, the current official exchange rates are not a good “equalizer.” We have to go through the “typical consumers’ baskets” of the needs of an individual (or a household) that have to be bought in a certain period (week or month). These “baskets” represent the cost of living and have to be compared with personal (or household) income for the same period. Then and only then we can have a more precise international comparison of living standards for the given countries.

- When using various quantitative data-series (monetary, physical, and so forth) for statistical “massaging” and modeling, the “technique of transformation of absolute values into growth rates” has proved to yield the best and most statistically credible result (Karasek 1988: 33, 73-75).

To conclude the almost impossible task of international comparisons of income and output statistics, we should heed the advice of Oskar Morgenstern:

- 10% to 30% error can be expected in any real numerical (economic) datum (Morgenstern 1963: Ch. 6, fn. 14 ).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Herick, B., and C. P. Kindleberger. 1983. Economic Development. McGraw-Hill Book Co.

- Karasek, Mirek, Waddah K. Alem, and Wasfy B. Iskander. 1988. Socio-Economic Modelling & Forecasting in Lesser Developed Countries. London: The Book Guild Ltd. ISBN 0863322204

- Karasek, Mirek. 2005. Institutional and Political Challenges and Opportunities for Integration in Central Asia. CAG Portal Forum 2005. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- Kuznets, Simon. 1934. National Income, 1929-1932 73rd US Congress, 2d session, Senate document no. 124, 7. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- Kuznets, Simon. 1948. Discussion of the new Department of Commerce Income Series; National Income: a new version. The Review of Economics and Statistics XXX(3): 151-179.

- Kuznets, Simon. 1956. Quantitative Aspects of the Economic Growth of Nations. I. Levels and Variability of Rates of Growth. Economic Development and Cultural Change 5: 1-94.

- Kuznets, Simon. How To Judge Quality. The New Republic, October 20, 1962

- Kuznets, Simon. 1966. Modern Economic Growth, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Kuznets, Simon. 1971. Economic Growth of Nations: Total Output and Production Structure, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mings, Turley, and Matthew Marlin. 2000. The Study of Economics: Principles, Concepts, and Applications, 6th ed. Dushkin/McGraw-Hill.

- Morgenstern, O. 1963. On the Accuracy of Economic Observations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Shostak, Frank. 2001. What is up with the GDP? Von Mises Institute Papers, 23/8/2001

- Cobb, Clifford, Ted Halstead, and Jonathan Rowe. 1995. If the GDP is up, why is America down? The Atlantic Monthly 276(4): 59-78. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

External links

- Historicalstatistics.org: Links to historical national accounts and statistics for different countries and regions

- World Bank's Development and Education Program Website

Global

- Australian Bureau of Statistics Manual on GDP measurement

- GDP-indexed bonds

- GDP scaled maps

- Euro area GDP growth rate (since 1996) as compared to the Bank Rate (since 2000)

- World Development Indicators (WDI)

- Economist Country Briefings

- UN Statistical Databases

- GDP Animated Cartogram.

Data

- Bureau of Economic Analysis: Official United States GDP data

- Historicalstatistics.org: Links to historical statistics on GDP for different countries and regions

- Complete listing of countries by GDP: Current Exchange Rate Method Purchasing Power Parity Method

- Historical US GDP (1790 to 2005)

Articles and books

- What's wrong with the GDP?

- Limitations of GDP Statistics by Schenk, Robert.

- whether output and CPI inflation are mismeasured, by Nouriel Roubini and David Backus, in Lectures in Macroeconomics

- "Measurement of the Aggregate Economy", chapter 22 of Dr. Roger A. McCain's Essential Principles of Economics: A Hypermedia Text

- Growth, Accumulation, Crisis: With New Macroeconomic Data for Sweden 1800-2000 by Rodney Edvinsson

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Measures_of_national_income_and_output history

- Gross_domestic_product history

- Gross_National_Income history

- Net_National_Product history

- Net_National_Income history

- Net_domestic_product history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.