Difference between revisions of "Maliseet" - New World Encyclopedia

(making page) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) (imported) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

[[Category:Ethnic group]] | [[Category:Ethnic group]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Cleanup|date=March 2007}} | ||

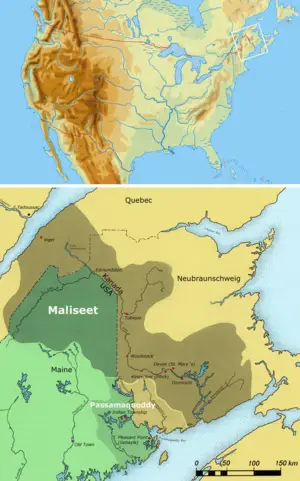

| + | [[Image:Wohngebiet_Maliseet.png|thumb|right|300px|Maliseet Territory]]The '''Maliseet''' (or '''''Wolastoqiyik''''') are a [[Wabanaki]] [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native American]]/[[First Nations]] people who inhabit the [[Saint John River]] valley and its tributaries, between [[New Brunswick]], [[Quebec]], and [[Maine]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Name == | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Maliseet are also known as ''Wolastoqiyik'', ''Malecite'', and in French also as ''Malécites'' or ''Étchemins'' (the latter collectively referring to the Maliseet and [[Passamaquoddy]].) | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Wolastoqiyik''' is the proper name for the people and their language. They named themselves after the '''[[Wolastoq]]''' river, now commonly known as the [[St. John River]], on which their territory and existence were centered. ''Wolastoq'' means "bright river" or "shining river" ("wol-" = good, "-as-" shining, "-toq" = river; "-iyik" = people of, equivalent e.g. of "-ians" or "-ites"). ''Wolastoqiyik'' therefore simply means "People of the Bright River," in their own language.<ref>LeSourd, Philip, ed. 2007. ''Tales from Maliseet Country: the Maliseet texts of Karl V. Teeter''. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska. p. 17, fnote 4</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Maliseet''' is the name by which the [[Mi'kmaq]] described them to early Europeans. "Maliseet" was a Mi'kmaq word meaning "broken talkers" or "lazy speakers";<ref>Erickson, Vincent O. 1978. "Maliseet-Passamaquoddy." In ''Northeast'', ed. Bruce G. Trigger. Vol. 15 of ''Handbook of North American Indians'', ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, pg. 135. Cited in Campbell, Lyle (1997). ''American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pg. 401.</ref> the Wolastoqiyik and Mi'kmaq languages are fairly closely related, but the name reflected what the Mi'kmaq perceived to be a sufficiently different dialect to be a "broken" version of their own language. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==History== | ||

| + | {{Sectstub}} | ||

| + | In the [[Jay Treaty]] of 1794, the Maliseet were granted free travel between the [[United States]] and [[Canada]] because their territory spanned both sides of the border. During the 1800s, intermarriage between the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy and European settlers was not unusual, particularly among the growing community of Scottish Canadian frontiersmen. When the [[Treaty of Ghent]] was signed, ending the [[War of 1812]], a significant portion of the Maliseet/Passamaquoddy territory was ceded from British Canada to the United States, in what is now northern Maine. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Culture== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Maliseet customs and [[Maliseet language|language]] are very similar to those of the neighboring [[Passamaquoddy]] (or ''Peskotomuhkati''), and largely similar to those of the [[Mi'kmaq]] and [[Penobscot]] tribes, although the Maliseet are considered to have pursued a primarily [[Agriculture|agrarian]] economy. They also shared some land with those peoples. The Maliseet and Passamaquoddy languages are similar enough that they are properly considered slightly different dialects of the same language, and are typically not differentiated for study. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several French and English words made their way into Maliseet from the earliest European contact. One Maliseet word also made its way into English: "Mus," or [[Moose]], for the unfamiliar creature the English speakers found in the woods where the Maliseet lived and had no name for in their own language. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Before contact with the Europeans, the traditional culture of both the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy generally involved travelling downstream on their rivers in the spring, and back upstream in the autumn. When they had finished travelling downstream in the spring, they congregated in larger groups near the ocean, and planted crops, largely of corn (maize), beans, squash. In the autumn, after the harvest, they travelled back upstream, taking provisions, and spreading out in smaller groups into the larger countryside to hunt game during the winter. Fishing was also a major source of resources throughout the year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Current Situation== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Today, within New Brunswick, approximately 3,000 Maliseets currently live within the [[Madawaska First Nation|Madawaska]], [[Tobique First Nation|Tobique]], [[Woodstock First Nation|Woodstock]], [[Kingsclear First Nation|Kingsclear]], [[Saint Mary's First Nation|Saint Mary's]] and [[Oromocto First Nation|Oromocto]] [[First Nations]]. There are also 600 in the Houlton Band in Maine and 200 in the [[Viger First Nation]] in Quebec. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are about 650 remaining native speakers of Maliseet and about 1,000 of Passamaquoddy, living on both sides of the border between New Brunswick and Maine; most are older, although some young people have begun studying and retaining the language, and the numbers of speakers is seen to have potentially stabilized. An active program of scholarship on the Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language takes place at the [[Mi'kmaq - Maliseet Institute]] at the [[University of New Brunswick]], in collaboration with the native speakers, particularly [[David Francis Sr.]], a Passamaquoddy elder living in [[Sipayik]], [[Maine]]. The Institute actively aims at helping Native American students master their native languages. Linguist [[Philip LeSourd]] has done extensive research on the language. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Ceremonies and Beliefs== | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Interesting Facts == | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | <references /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | * [http://www.native-languages.org/maliseet.htm Maliseet language and culture links] | ||

| + | * [http://www.schoolnet.ca/aboriginal/audiosam/maliseet/malis-e.html Audio files of samples of Maliseet speech by a native speaker] | ||

| + | * [http://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Test-wp/pqm/ Maliseet Test Wikipedia] | ||

| + | * [http://www.unbf.ca/education/mmi/ Mi'kmaq-Maliseet Institute - University of New Brunswick] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Credits|Maliseet|210849650|}} | ||

Revision as of 23:20, 27 May 2008

Template:Cleanup

The Maliseet (or Wolastoqiyik) are a Wabanaki Native American/First Nations people who inhabit the Saint John River valley and its tributaries, between New Brunswick, Quebec, and Maine.

Name

The Maliseet are also known as Wolastoqiyik, Malecite, and in French also as Malécites or Étchemins (the latter collectively referring to the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy.)

Wolastoqiyik is the proper name for the people and their language. They named themselves after the Wolastoq river, now commonly known as the St. John River, on which their territory and existence were centered. Wolastoq means "bright river" or "shining river" ("wol-" = good, "-as-" shining, "-toq" = river; "-iyik" = people of, equivalent e.g. of "-ians" or "-ites"). Wolastoqiyik therefore simply means "People of the Bright River," in their own language.[1]

Maliseet is the name by which the Mi'kmaq described them to early Europeans. "Maliseet" was a Mi'kmaq word meaning "broken talkers" or "lazy speakers";[2] the Wolastoqiyik and Mi'kmaq languages are fairly closely related, but the name reflected what the Mi'kmaq perceived to be a sufficiently different dialect to be a "broken" version of their own language.

History

In the Jay Treaty of 1794, the Maliseet were granted free travel between the United States and Canada because their territory spanned both sides of the border. During the 1800s, intermarriage between the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy and European settlers was not unusual, particularly among the growing community of Scottish Canadian frontiersmen. When the Treaty of Ghent was signed, ending the War of 1812, a significant portion of the Maliseet/Passamaquoddy territory was ceded from British Canada to the United States, in what is now northern Maine.

Culture

The Maliseet customs and language are very similar to those of the neighboring Passamaquoddy (or Peskotomuhkati), and largely similar to those of the Mi'kmaq and Penobscot tribes, although the Maliseet are considered to have pursued a primarily agrarian economy. They also shared some land with those peoples. The Maliseet and Passamaquoddy languages are similar enough that they are properly considered slightly different dialects of the same language, and are typically not differentiated for study.

Several French and English words made their way into Maliseet from the earliest European contact. One Maliseet word also made its way into English: "Mus," or Moose, for the unfamiliar creature the English speakers found in the woods where the Maliseet lived and had no name for in their own language.

Before contact with the Europeans, the traditional culture of both the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy generally involved travelling downstream on their rivers in the spring, and back upstream in the autumn. When they had finished travelling downstream in the spring, they congregated in larger groups near the ocean, and planted crops, largely of corn (maize), beans, squash. In the autumn, after the harvest, they travelled back upstream, taking provisions, and spreading out in smaller groups into the larger countryside to hunt game during the winter. Fishing was also a major source of resources throughout the year.

Current Situation

Today, within New Brunswick, approximately 3,000 Maliseets currently live within the Madawaska, Tobique, Woodstock, Kingsclear, Saint Mary's and Oromocto First Nations. There are also 600 in the Houlton Band in Maine and 200 in the Viger First Nation in Quebec.

There are about 650 remaining native speakers of Maliseet and about 1,000 of Passamaquoddy, living on both sides of the border between New Brunswick and Maine; most are older, although some young people have begun studying and retaining the language, and the numbers of speakers is seen to have potentially stabilized. An active program of scholarship on the Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language takes place at the Mi'kmaq - Maliseet Institute at the University of New Brunswick, in collaboration with the native speakers, particularly David Francis Sr., a Passamaquoddy elder living in Sipayik, Maine. The Institute actively aims at helping Native American students master their native languages. Linguist Philip LeSourd has done extensive research on the language.

Ceremonies and Beliefs

Interesting Facts

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ LeSourd, Philip, ed. 2007. Tales from Maliseet Country: the Maliseet texts of Karl V. Teeter. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska. p. 17, fnote 4

- ↑ Erickson, Vincent O. 1978. "Maliseet-Passamaquoddy." In Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger. Vol. 15 of Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, pg. 135. Cited in Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pg. 401.

External links

- Maliseet language and culture links

- Audio files of samples of Maliseet speech by a native speaker

- Maliseet Test Wikipedia

- Mi'kmaq-Maliseet Institute - University of New Brunswick

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.