Ljubljana

| Ljubljana | |

| Triple Bridge above the Ljubljanica River and Prešeren Square | |

| Municipal location in Slovenia | |

| Coordinates: {{#invoke:Coordinates|coord}}{{#coordinates:46|3|5|N|14|30|20|E|type:city | |

|---|---|

| name= }} | |

| Country | Slovenia |

| First mention | 1144 |

| Government | |

| - Mayor and governor | Zoran Janković (Lista Zorana Jankovića) |

| Area | |

| - Total | 275.0 km² (106.2 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 298 m (978 ft) |

| Population (2007)[1] | |

| - Total | 267,920 |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| - Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) |

| Area code(s) | 01 |

| Vehicle Registration | LJ |

| Website: www.ljubljana.si | |

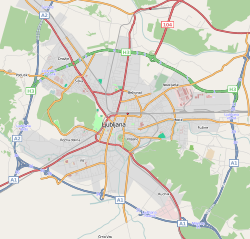

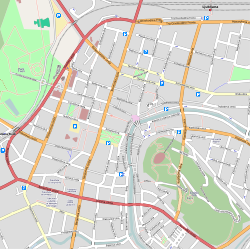

Ljubljana ([ʎub'ʎana] ) is the capital city of Slovenia and its largest town. It is located in the center of the country and is a mid-sized city of some 270,000 inhabitants. Ljubljana is regarded as the cultural, scientific, economic, political and administrative center of Slovenia, independent since 1991. Throughout its history, it has been influenced by its geographic position at the crossroads of Germanic, Latin and Slavic culture.

Its transport connections, concentration of industry, scientific and research institutions and industrial tradition are contributing factors to its leading economic position. Ljubljana is the seat of the central government, administrative bodies and all government ministries of Slovenia. It is also the seat of Parliament and of the Office of the President.

Geography

Historians disagree about the origins of the name Ljubljana. It could derive from the ancient Slavic city called Laburus,[2] or from the Latin Aluviana after a flood in the town, from Laubach ("marsh"), or it could come from the Slavic word Luba, which means "beloved".[2]. The old German name for the city is Laibach.

The city, with an area of 275.0 square kilometers (106.2 sq mi), is situated on an alluvial plain in central Slovenia, near the confluence of the rivers Ljubljanica and Sava, at the foot of Castle Hill, at an altitude of 298 meters (980 ft) in the valley of the river Ljubljanica[3] between the Kras region and the Julian Alps.[4] The castle, which sits atop a hill south of the city centre, is at 366 meters (1,200 ft) altitude while the city's highest point, called Janški Hrib, reaches 794 meters (2,600 ft).[5]

The Ljubljana's climate, and that of eastern Slovenia, is of the continental type.[3] July is the hottest month, with an average daily maximum temperature of 35.6°F (2°C), while January is one of the the coldest, with an average daily maximum temperature of 80.6°F (27°C).[6] Frost is possible from October through May. The driest months are from January to April. Average annual precipitation is 54.4 inches (1383mm).

Size – land area, size comparison

A number of earthquakes have devastated Ljubljana, including in 1511 and 1895.[7] Slovenia is in a rather active seismic zone because of its position to the south of the Eurasian Plate.[8]

Districts

History

Around 2000 B.C.E., the Ljubljana Marshes were settled by people living in wooden structures on pilotis. These people lived through hunting, fishing and primitive agriculture. To get around the marshes, they used dugout canoes made by cutting out the inside of tree trunks. Later, the area remained a transit point for numerous tribes and peoples.[9] The land was first settled by the Veneti, followed by an Illyrian tribe called the Yapodi and then in the 3rd century B.C.E. a Celtic tribe, the Taurisci.[9]

According to legend, Ljubljana was founded by the Greek mythological hero Jason and his companions, the Argonauts, who had stolen the golden fleece from King Aetes and fled from him across the Black Sea and up the Danube, Sava and Ljubljanica rivers. They stopped at a large lake in the marsh near the source of the Ljubljanica, where they disassembled their ship to carry it to the Adriatic Sea, and return to Greece. The lake where they stopped had a monster. Jason fought the monster, and killed it. The monster, is referred to as the Ljubljana Dragon, and is part of the Ljubljana coat of arms.

Around 50 B.C.E., the Romans built a military encampment that later became a permanent settlement called Iulia Aemona (Emona).[10] This entrenched fort was occupied by the Legio XV Apollinaris.[11] The settlement was strategically important, located on the route to Pannonia and commanding the Ljubljana Gap.

In 452, it was destroyed by the Huns under Attila's orders,[10] and later by the Ostrogoths and the Lombards.[12]

Emona housed 5000 to 6000 inhabitants and played an important role during numerous battles. Its plastered brick houses, painted in different colours, were already connected to a drainage system.[10]

In the sixth century, the ancestors of the Slovenes moved in. In the ninth century, the Slovenes fell under Frankish domination, while experiencing frequent Magyar raids.[13]

The name of the city, Luwigana, appears for the first time in a document from 1144.[12] In the 13th century, the town was composed of three zones: the Stari trg ("Old Square"), the Mestni trg ("Town Square") and the Novi trg ("New Square").[13] In 1220, Ljubljana was granted city rights, including the right to coin its own money.[13]

In 1270, Carniola and in particular Ljubljana was conquered by King Ottokar II of Bohemia (1230–1278).[13] When he was in turn defeated by Rudolph of Habsburg (1218–1291),[12] the latter took the town in 1278.[13] Renamed Laibach, it would belong to the House of Habsburg until 1797.[12] The Diocese of Ljubljana was established in 1461 and the Church of St. Nicholas became a cathedral.[13]

In the 15th century Ljubljana became recognized for its art. After an earthquake in 1511, it was rebuilt in Renaissance style and a new wall was built around it.[14] In the 16th century, the population numbered 5000, 70 percent of whom spoke Slovene as their mother tongue, with most of the rest using German.[14] In 1550, the first two books written in Slovene were published there: a catechism and an abecedarium, followed by a Bible translation. By that time, the Protestant reformation had gained ground in the town. Several important Lutheran preachers lived and worked in Ljubljana, including Primož Trubar (1508–1586), Adam Bohorič (1520-1598) and Jurij Dalmatin (1547-1589).

Around the same time, the first secondary school, public library and printing house opened in Ljubljana.[14] Ljubljana thus became the undisputed center of Slovenian culture, a position maintained thereafter. In 1597, the Jesuits arrived in the city and established a new secondary school that later became a college. Baroque architecture appeared at the end of the 17th century as foreign architects and sculptors came in.[14]

The Napoleonic interlude saw Ljubljana become, from 1809 to 1813, the capital of the Illyrian Provinces.[12][15]

In 1815, the city became Austrian again and from 1816 to 1849 was part of the Kingdom of Illyria. In 1821 it hosted the Congress of Laibach, which fixed European political borders for years to come.[7] The first train arrived in 1849 from Vienna and in 1857 the line was extended to Trieste.[15] Public electric lighting appeared in 1898.[15]

In 1895, Ljubljana, then a city of 31,000, suffered a serious earthquake measuring 6.1 on the Richter scale. Some 10 percent of its 1400 buildings were destroyed, although casualties were light. During the reconstruction that followed, a number of quarters were rebuilt in Art Nouveau style.[15]

In 1918, after the end of World War I (1914-1918) and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the region joined the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.[12][16] In 1929, Ljubljana became the capital of Drava Banovina, a Yugoslav province.[17] In 1941, during World War II (1939-1945), Fascist Italy occupied the city, followed by Nazi Germany in 1943.[16] In Ljubljana, the occupying forces established strongholds and command centers of Quisling organisations, the Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia under Italy and the Home Guard under German occupation. The city was surrounded by over 30 kilometers (19 mi) of barbed wire to prevent co-operation between the underground resistance movement (Liberation Front of the Slovenian People) within the city and the Yugoslav Partisans (Partizani) who operated outside the fence. Since 1985, a commemorative path has ringed the city where this iron fence once stood.[18].

After World War II, Ljubljana became the capital of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, part of Communist Yugoslavia, a status it retained until 1991, when Slovenia became independent. Ljubljana remained the capital of Slovenia, which entered the European Union in 2004.[16]

Government

Slovenia is a parliamentary republic in which the president, who is elected by popular vote for a five-year term and is eligible for a second term, is chief of state, and the prime minister, who is the leader of the majority party elected every four years, is head of government.

The bicameral parliament consists of a National Assembly, or Drzavni Zbor, of which 40 members are directly elected and 50 are elected on a proportional basis, and the National Council, or Drzavni Svet, of 40 members indirectly elected by an electoral college to serve five-year terms.

Municipal elections take place every four years. Between 2002 and 2006, Danica Simšič was mayor.[5] Since the municipal elections of 22 October 2006, Zoran Janković, an important businessman in Slovenia, has been the mayor of Ljubljana, having won 62.99% of the votes.[19] The majority on the city council (the mayor's own party) holds 23 of 45 seats.[19] Among other roles, the council drafts the municipal budget, and is assisted by various boards active in the fields of health, sports, finances, education, environmental protection and tourism.[20] The Ljubljana electoral zone is also composed of 17 districts that have local authorities working with the city council to make known citizens' suggestions and prepare activities in their districts.[21]

The jurisdiction of the Ljubljana police (Policija) covers an area of 3,807 square kilometers (1,470 sq mi), which represents 18.8% of the national territory.[22] There are 17 police stations employing 1,380 individuals, of whom 1,191 are police officers and 189 are civilians.[22] With around 45,000 criminal acts in 2007, the Ljubljana police district alone accounts for over 50% of the country's crimes.[23] Slovenia and in particular Ljubljana have a quiet and secure reputation.[24]

Districts

Ljubljana has 17 districts, listed below. It was formerly composed of five municipalities (Bežigrad, Center, Moste-Polje, Šiška and Vič-Rudnik) that still correspond to the main electoral constituencies of the city.

|

|

Economy

Slovenia is a model of economic success and stability for the region [25]. With the highest per capita GDP in Central Europe, Slovenia has excellent infrastructure, a well-educated work force, and a strategic location between the Balkans and Western Europe.

Slovenia's per capita GDP was estimated at $30,800 in 2008. Ljubljana produces about 25% of Slovenia's GDP.[3]

In 2003, the level of active working population in Ljubljana was 62 percent, of which 64 percent worked in the private sector and 36 percent in the public sector.[3] In January 2007, the unemployment rate was 6.5 percent (down from 7.7 percent a year earlier), compared with a national average of 8.7 percent.[26]

The Ljubljana Stock Exchange (Ljubljanska borza), purchased in 2008 by the Vienna Stock Exchange,[27] deals with large Slovenian companies. Some of these have their headquarters in the capital region: for example, the retail chain Mercator, the oil company Petrol d.d. and the telecommunications concern Telekom Slovenije.[28] Over 15,000 enterprises operate in the city, most of them in the service sector]].[29]

Industry remains the city's most important employer, notably in the pharmaceuticals, petrochemicals and food processing.[3] Other fields include banking, finance, transport, construction, skilled trades and services and tourism. The public sector provides jobs in education, culture, health care and local administration.[3]

Ljubljana is at the centre of the Slovenian road network, and is an important centre of rail and road links with Austria, Croatia, Hungary, and Italy.

Ljubljana railway station is part of a railway network that links Germany to Croatia through the Munich-Salzburg-Ljubljana-Zagreb line. A second network is the Vienna-Graz-Maribor-Ljubljana one, which links Austria to Slovenia. A third is the Genoa-Venice-Ljubljana one, linking Ljubljana to Italy. Finally, a line goes to Budapest.[4]

Ljubljana Airport (IATA code LJU), located 26 kilometers (16 mi) north of the city, has flights to numerous European destinations.

The bus network, run by the city-owned Ljubljanski potniški promet, is Ljubljana's only current means of public transportation.

Demographics

Population, population rank Race/ethnicity - historical background of ethnic groups Language Religion Colleges and universities

In 1869, Ljubljana had just under 27,000 inhabitants,[30] a figure that grew to 80,000 by the mid-1930s.[16] Demographic growth remained fairly stable between 1999 and 2007, with a population of about 270,000.[1] Before 1996, the city's population surpassed 320,000 but the drop that year was mainly caused by a territorial reorganisation that saw certain peripheral districts attached to neighbouring municipalities.[5] At the 2002 census, 39.2% of Ljubljana residents were Roman Catholic; 30.4% were believers who did not belong to a religion, unknown or did not reply; 19.2% were atheist; 5.5% were Eastern Orthodox; 5.0% were Muslim; and the remaining 0.7% were Protestant or belonged to other religions.[31]

| 1869 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1931 | 1935 | 1948 | 1953 | 1961 | 1966 | 1970 | 1980 | 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26,879 | 32,265 | 36,878 | 45,017 | 56,844 | 79,391 | 85,000 | 98,914 | 113,666 | 135,806 | 154,690 | 180,714 | 265,000 | 270,032 |

Education

The Academy of the Industrious (Academia operosorum Labacensis) opened in 1693; it closed in 1801 but was a precursor to the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, founded in 1938. Today, students make up one-seventh of Ljubljana's population, giving the city a youthful character.[32] The University of Ljubljana, Slovenia's most important and Ljubljana's only university, was founded in 1919.[16] As of 2008, it has 22 faculties, three academies and a college. These offer Slovenian-language courses in (among other subjects) medicine, applied sciences, arts, law and administration.[33] The university has close to 64,000 students and some 4,000 teaching faculty.

In 2004, the national library and university library had 1,169,090 books in all.[5] In 2006, the 55 primary schools had 20,802 pupils and the 32 secondary schools had 25,797.[5]

Culture

Ljubljana has numerous art galleries and museums. In 2004, there were 15 museums, 41 art galleries, 11 theatres and four professional orchestras.[5] There is for example an architecture museum, a railway museum, a sports museum, a museum of modern art, a brewery museum, the Slovenian Museum of Natural History and the Slovene Ethnographic Museum.[34] The Ljubljana Zoo covers 19.6 hectares (48 acres) and has 152 animal species. An antique flea market takes place every Sunday in the old city.[34] In 2006, the museums received 264,470 visitors, the galleries 403,890 and the theatres 396,440.[5]

Each year over 10,000 cultural events take place in the city; among these are ten international festivals of theatre, music and art generally.[7] Numerous music festivals are held there, chiefly in European classical music and jazz, for instance the Ljubljana Summer Festival (Ljubljanski poletni festival). In the centre of the various Slovenian wine regions, Ljubljana is known for being a "city of wine and vine". Grapevines were already being planted on the slopes leading up to the Castle Hill by the Roman inhabitants of Emona.[7]

In 1701, present-day Slovenia's first philharmonic academy opened in Ljubljana, which spurred the development of musical production in the region.[7] Some of its honorary members would include Joseph Haydn, Ludwig van Beethoven and Johannes Brahms, as well as the violinist Niccolò Paganini.[7] Early in his career, Gustav Mahler served as conductor at the opera house, giving eighty-four complete performances between September 1881 and April 1882.[35]

The National Gallery (Narodna galerija), founded in 1918,[16] and the Museum of Modern Art (Moderna galerija), both in Ljubljana, exhibit the most famous Slovenian artists (among then Franz Caucig, 1755-1828). On Metelkova street there is a social centre dedicated to alternative culture, set up in a renovated former Austro-Hungarian barracks.[36] This lively street has numerous clubs and concert halls that play various types of music, mainly alternative rock.[37] In the 1980s, Ljubljana became the centre of the Neue Slowenische Kunst, which among others included the music group Laibach and the painters of the IRWIN collective; the philosopher Slavoj Žižek was also associated with it.

Architecture

Despite the appearance of large buildings, especially at the city's edge, Ljubljana's historic centre remains intact; there, Baroque and Art Nouveau styles mix. The city is strongly influenced by the Austrian fashion in the style of Graz and Salzburg.

The old city is made up of two districts: one includes Ljubljana town hall and the principal architectural works; the other, the neighbourhood of the Chevaliers de la Croix, features the Ursuline church, the philharmonic society building (1702) and the Cankar house.

After the 1511 earthquake, Ljubljana was rebuilt in a Baroque style following the model of a Renaissance town; after the 1895 quake, which severely damaged the city, it was once again rebuilt, this time in an Art Nouveau style.[7][15] The city's architecture is thus a mix of styles. The large sectors built after the Second World War often include a personal touch by the Slovene architect Jože Plečnik.

Ljubljana Castle dominates the hill over the river Ljubljanica. Built in the 12th century, the castle was the residence of the Margraves, later the Dukes of Carinthia. Aside from the castle, the city's main architectural works are St. Nicholas Cathedral, St. Peter's Church, the Franciscan Church of the Annunciation, the Triple Bridge and the Dragon Bridge.

Near town hall, on the Mestni Trg square, is Robba's fountain, in Baroque style. Resembling the fountain on Rome's Piazza Navona, it is decorated with an obelisk at the foot of which are three figures in white marble symbolising the three chief rivers of Carniola. It is the work of Francesco Robba, who designed numerous other Baroque statues in the city. Ljubljana's churches are equally marked by this style that gained currency following the 1511 earthquake.[38]

For its part, Art Nouveau features prominently on Prešeren Square and on the Dragon Bridge.[39] Among the important influences on the city was the architect Jože Plečnik, who designed several bridges, including the Triple Bridge, as well as the National Library.[40] Nebotičnik is a notable high-rise.

- TownHall-Ljubljana.JPG

Ljubljana town hall

- SLO-Ljubljana20.JPG

Mestni Trg square with Robba's fountain and St. Nicholas Cathedral in the background

- LjubljanaFrančiškanska072008.JPG

The Franciscan Church of the Annunciation with the monument to France Prešeren at right and the Triple Bridge in the foreground

- StPeter-Ljubljana.JPG

St. Peter's Church

- UrbancevaHisa-Ljubljana.JPG

The Art Nouveau Urbanc House on Prešeren Square

- Neboticnik-Ljubljana.JPG

Nebotičnik

Ljubljana Castle

Ljubljana Castle (Ljubljanski grad) is a mediaeval castle located at the summit of the hill that dominates the city centre. The area surrounding today's castle has been continuously inhabited since 1200 B.C.E.[41] The hill summit probably became a Roman army stronghold after fortifications were built in Illyrian and Celtic times.[41]

The castle is first mentioned in 1144 as the seat of the Duchy of Carinthia. The fortress was destroyed when the duchy became part of the Habsburg domains in 1335.[42] Between 1485 and 1495, the present castle was built and furnished with towers. Its purpose was to defend the empire against Ottoman invasion as well as peasant revolt.[42] In the 17th and 18th centuries, the castle became an arsenal and a military hospital. It was damaged during the Napoleonic period and, once back in the Austrian Empire, became a prison, which it remained until 1905, resuming that function during World War II.[42][41] The castle's Outlook Tower dates to 1848; this was inhabited by a guard whose duty it was to fire cannons warning the city in case of fire or announcing important visitors or events.[41]

In 1905, the city of Ljubljana purchased the castle, which underwent a renovation in the 1960s. Today, it is a tourist attraction; cultural events also take place there.[43] Since 2007, a funicular has linked the city centre to the castle atop the hill.[42].

St. Nicholas Cathedral

St. Nicholas Cathedral of Ljubljana (Stolnica svetega Nikolaja) is the city's only cathedral. Easily identifiable due to its green dome and twin towers, it is located on Vodnik square near the Triple Bridge.[44]

Originally, the site was occupied by a three-nave Romanesque church first mentioned in 1262.[44] After a fire in 1361 it was re-vaulted in Gothic style. The Diocese of Ljubljana was set up in 1461 and eight years later, a new fire presumably set by the Ottomans once again burnt down the building.[44]

Between 1701 and 1706, the Jesuit architect Andrea Pozzo designed a new Baroque church with two side chapels shaped in the form of a Latin cross.[44] The dome was built in the centre in 1841.[44]The interior is decorated with Baroque frescos painted by Giulio Quaglio between 1703-1706 and 1721-1723.[44]

Dragon Bridge

The Dragon Bridge (Zmajski most) was built between 1900 and 1901, when the city was part of Austria-Hungary. Designed by a Dalmatian architect who studied in Vienna and built by an Austrian engineer, the bridge is considered one of the finest works in the Vienna Secession Art Nouveau style.[45][46] Some residents nicknamed the bridge "mother-in-law" in reference to the fearsome dragons on its four corners.[47]

Sports

Ljubljana's ice hockey clubs are HD HS Olimpija, ŠD Alfa, HK Slavija and HDD Olimpija Ljubljana. They all compete in the Slovenian Hockey League; HDD Olimpija Ljubljana also takes part in the Austrian Hockey League.[48] The basketball teams are KD Slovan, ŽKD Ježica Ljubljana and KK Union Olimpija. The latter, which has a green dragon as its mascot, hosts its matches in the 6,000-seat Tivoli Arena (Dvorana Tivoli),[49] also the home rink of HDD Olimpija Ljubljana.

The city's football team which plays in the Slovenian PrvaLiga is Interblock Ljubljana.[50] NK Olimpija Ljubljana play in the Slovenian Second League.

Each year since 1957, on 8-10 May, the traditional recreational March along the Path around Ljubljana has taken place to mark the liberation of Ljubljana on 9 May 1945.[51] The last Sunday in October, the Ljubljana Marathon is run on the city's streets. It attracts several thousand runners each year.[52]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Population by age groups and sex, municipalities, Slovenia. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Where Did Ljubljana Get Its Name From?. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Location and General Data. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Ljubljana in Numbers. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Average Conditions: Ljubljana, Slovenia. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Location and General Data. Retrieved 2008-07-30. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "InfoIntro" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Seismology. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 The First Settlers of Ljubljana. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 The Times of the Roman Emona. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ (French) Hildegard Temporini and Wolfgang Haase, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. de Gruyter, 1988. ISBN 3-110-11893-9. Google Books, p.343

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedArtis - ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Ljubljana in the Middle Ages. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Reformation and Counter-reformation; Renaissance and Baroque. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Ljubljana in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 The Turbulent 20th Century. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Dans la Yougoslavie des Karageorgévitch (in French). Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Template:Sl icon/(English) The Path of Remembrance and Comradeship. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 The Mayor of the City of Ljubljana. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Boards of the City Council. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ District authorities. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Police directorate Ljubljana. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Annual Report on the Work of the Police 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Precautions to take (in French). Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ World Fact Book 2009 Slovenia Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ↑ Registered unemployment rates (%) by regional offices in 2006 and 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Austrians Buy Ljubljana Stock Exchange. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Ljubljanska borza d.d.. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Ljubljana: economic center of Slovenia. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Krajevni leksikon Slovenije (Ljubljana: DZS, 1995), p.297

- ↑ Population by religion, municipalities, Slovenia, Census 2002. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ UL history. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Statutes of UL. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Museums. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Raymond Holden (2005). The Virtuoso Conductors. New Haven: Yale University Press, 65. ISBN 0300093268.

- ↑ Metelkova mesto alternative culture centre. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ AKC Metelkova mesto. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Baroque Ljubljana. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Art Nouveau in Ljubljana. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Jože Plečnik and His Work. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Ljubljanski grad / Ljubljana Castle. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 City castle in Ljubljana. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Festival Ljubljana. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 Stolnica (Cerkev sv. Nikolaja) / The Cathedral (Church of St. Nicholas). Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ C. Abdunur (2001). ARCH'01: Troisième conférence internationale sur les ponts en arc (in French). Presses des Ponts, 124. ISBN 2859783474.

- ↑ Zmajski most / Dragon Bridge. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ↑ Robin McKelvie, Jenny McKelvie (2005). Slovenia: The Bradt Travel Guide. Robin McKelvie, 84. ISBN 1841621196.

- ↑ Hokejske Selekcije Olimpija (in Slovenian). Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Union Olimpija (in Slovenian). Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ NK Interblock. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Thousands Join Ljubljana Hike (in English). Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ 13th Ljubljana marathon – record participation! (in English). Retrieved 2008-11-01.

Further reading

- Arnez, John A. 1958. Slovenia in European affairs, reflections on Slovenian political history. New York: League of CSA.

- Curtis, Glenn E. 1992. Yugoslavia: a country study. Area handbook series, 550-99. Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0844407356

- Davenport, Fionn. 2006. Best of Ljubljana. Footscray, Vic: Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781741048247

- Dežman, Jože. 2006. The Making of Slovenia. Ljubljana: National Museum of Contemporary History. ISBN 9789619104026

- Fink Hafner, Danica, and John R. Robbins. 1997. Making a new nation: the formation of Slovenia. Aldershot, England: Dartmouth. ISBN 1855216566

- Kemperl, Metoda, Matej Klemenčič, and Igor Weigl. 2007. Baroque Ljubljana. Cultural and natural monuments of Slovenia, 210. Ljubljana: Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia. OCLC 255128131

- Ljubljana: the Bradt city guide. 2005. Chalfont St. Peter, Bucks, England: Bradt Travel Guides. OCLC 61751944

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.