Li Hongzhang

| Li Hongzhang 李鴻章 | |

| |

| In office 1871 – 1895 | |

| Preceded by | Zeng Guofan |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Wang Wenzhao |

| In office 1900 – 1901 | |

| Preceded by | Yu Lu |

| Succeeded by | Yuan Shikai |

| Born | February 15 1823 Hefei, Anhui, China |

| Died | November 7 1901 (aged 78) |

| This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

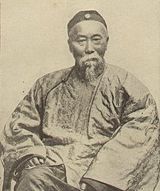

Li Hongzhang or Li Hung-chang (February 15, 1823 – November 7, 1901) was a Chinese general who ended several major rebellions, and a leading statesman of the late Qing Empire. He served in important positions of the Imperial Court, once holding the office of the Viceroy of Zhili.

He was best known in the west for his diplomatic negotiation skills. Since 1894 First Sino-Japanese War, Li had become a literary symbol for China's embarrassments in the late Qing Dynasty. His image in China remains largely controversial, with most criticizing his lack of political insight and his failure to win a single external military campaign against foreign powers, but praising his role as a pioneer of industry modernization in Late Qing, his diplomatic skills and his internal military campaigns against Taiping Rebellion.

Life

Li Hongzhang (李鴻章) was born in the village of Qunzhi (群治村) in Modian township (磨店鄉), 14 kilometers (9 miles) northeast of downtown Hefei, Anhui. From very early in life, he showed remarkable ability, and he became a shengyuan in the imperial examination system. In 1847, he obtained jinshi degree, the highest level in the Imperial examination system. Two years later gained admittance into the Hanlin Academy (翰林院). Shortly after this the central provinces of the empire were invaded by the Taiping rebels, and in defence of his native district he raised a regiment of militia. His service to the imperial cause attracted the attention of Zeng Guofan, the generalissimo in command.

In 1859, Li Hongzhang was transferred to the province of Fujian, where he was given the rank of taotai, or intendant of circuit. But at Zeng's request, Li was recalled to take part against the rebels. He found his cause supported by the "Ever Victorious Army," which, having been raised by an American named Frederick Townsend Ward, was placed under the command of Charles George Gordon. With this support Li gained numerous victories leading to the surrender of Suzhou and the capture of Nanjing. For these exploits, he was made governor of Jiangsu, was decorated with an imperial yellow jacket, and was enfeoffed as an earl.

An incident connected with the surrender of Suzhou, however, soured Li's relationship with Gordon. By an arrangement with Gordon, the rebel princes yielded Nanjing on condition that their lives should be spared. In spite of the agreement, Li ordered their instant execution. This breach of faith so infuriated Gordon that he seized a rifle, intending to shoot the falsifier of his word, and would have done so had Li not fled. On the suppression of the rebellion (1864), Li took up his duties as governor, but was not long allowed to remain in civil life. On the outbreak of the Nian Rebellion in Henan and Shandong (1866), he was ordered again to take to the field, and after some misadventures, he succeeded in suppressing the movement. A year later, he was appointed viceroy of Huguang, where he remained until 1870, when the Tianjin Massacre necessitated his transfer to the scene of the outrage. He was, as a natural consequence, appointed to the viceroyalty of the metropolitan province of Zhili, and justified his appointment by the energy with which he suppressed all attempts to keep alive the anti-foreign sentiment among the people. For his services, he was made imperial tutor and member of the grand council of the empire, and was decorated with many-eyed peacocks' feathers.

To his duties as viceroy were added those of the superintendent of trade, and from that time until his death, with a few intervals of retirement, he practically conducted the foreign policy of China. He concluded the Chefoo convention with Sir Thomas Wade (1876), and thus ended the difficulty caused by the murder of Mr. Margary in Yunnan; he arranged treaties with Peru and Japan, and he actively directed the Chinese policy in Korea.

| Li Hongzhang | |

| Names (details) | |

|---|---|

| Known in English as: | Li Hongzhang |

| Traditional Chinese: | 李鴻章 |

| Simplified Chinese: | 李鸿章 |

| Pinyin: | Lǐ Hóngzhāng |

| Wade-Giles: | Li Hung-chang |

| Courtesy names (字): | Jiànfǔ (漸甫) Zǐfù (子黻) |

| Pseudonyms (號): (Yisou and Shengxin used in his old age) |

Shǎoquán (少荃) Yísǒu (儀叟) Shěngxīn (省心) |

| Nickname: | Mr. Li the Second (李二先生) (i.e. 2nd son of his father) |

| Posthumous name: | Wénzhōng (文忠) (Refined and Loyal) |

On the death of the Tongzhi Emperor, in 1875, he, by suddenly introducing, a large armed force into the capital, effected a coup d'etat by which the Guangxu Emperor was put on the throne under the tutelage, of the two dowager empresses; and, in 1886, on the conclusion of the Franco-Chinese War, he arranged a treaty with France. Li was always strongly impressed with the necessity of strengthening the empire, and when viceroy of Zhili he raised a large well-drilled and well-armed force, and spent vast sums both in fortifying Port Arthur and the Taku forts and in increasing the navy. For years, he had watched the successful reforms effected in Japan and had a well-founded dread of coming into conflict with that empire.

Because of his prominent role in Chinese diplomacy in Korea and of his strong political connections in Manchuria, Li Hongzhang found himself leading Chinese forces during the disastrous Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). In fact, it was mostly the armies that he established and controlled that did the fighting, whereas other Chinese troops led by his rivals and political enemies did not come to their aid. The fact that some of his men were extremely corrupt further disadvantaged China from the beginning of the war. For instance, one official used ammunition funds for personal use. As a result, shells ran out for the some of the battleships during battle such that one navy commander, Deng Shichang, resorted to ramming the enemies' ship. The defeat of his relatively modernized troops and a small naval force at the hands of the Japanese greatly undermined his political standing, as well as the wider cause of the Self-Strengthening Movement.

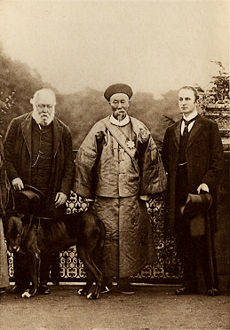

In 1896, he toured Europe and the United States of America, where he advocated reform of the American immigration policies that had greatly restricted Chinese immigration after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (renewed in 1892). (He also witnessed the 1896 Royal Naval Fleet Review at Spithead.) It was during his visit to Britain in 1896 that Queen Victoria made him a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order.[1]

Li Hongzhang played a major role in ending the Boxer Rebellion. In 1901, he was the principal Chinese negotiator with the foreign powers who had captured Beijing, and, on September 7, 1901, he signed the treaty (Boxer Protocol) ending the Boxer crisis, obtaining the departure of the foreign armies at the price of huge indemnities for China. Exhausted, he died two months later in Beijing.

Opinions and legacy

Since the First Sino-Japanese War (1894), Li Hongzhang has been generally a target of criticism and was portrayed in many ways as a traitor to the Chinese people, an infamous name that lives in history. Well-known negative comments from common Chinese people, such as "Actor Yang the Third is dead; Mr. Li the Second is the traitor" (杨三已死無蘇丑,李二先生是漢奸), have made the name Li Hongzhang a notorious trademark for traitors. Such a message is also echoed through textbooks and other forms of documents.

As early as 1885, General Tso, an equally famous but much more respected Chinese military leader, accused Li Hongzhang as a traitor. Although Chinese navy was eliminated in August 1884 at the Battle of Foochow, Chinese army won a decisive battle in March 1885, which brought about the fall of the Jules Ferry government in France. In July 1885, Li signed the Sino-French treaty to confirm the Treaty of Hué as if the time was still in the year 1884. General Tso could not understand Li's behavior. He predicted that Li would be notorious in the Chinese history records (“李鴻章誤盡蒼生,將落個千古罵名”).

According to Prince Esper Esperevich Ouchtomsky (1861-1921), the learned Russian orientalist and the Chief Executive of Russo Chinese Bank, Li Hongzhong accepted bribery of 3,000,000 Russian rubles (about US$1,900,000 at the time) at the time of signing the "Mutual Defense Treaty between China and Russia" on June 3, 1896. In his memoir "Strategic Victory over the Qing Dynasty," Prince Ouchtomsky wrote: "The day after the signing of the Mutual Defense Treaty between China and Russia, Romanov, the director of the general office of the Department of Treasury of the Russian Empire, chief officer Qitai Luo and I signed an agreement document to pay Li Hongzhang. The document stipulates that the first 1,000,000 rubles will be paid at the time when the Emperor of the Qing Dynasty announces the approval of constructing the Chinese Eastern Railway; the second 1,000,000 rubles will be paid at the time of signing the contract to build the railway and deciding the route of the railway; the last 1,000,000 rubles will be paid at the time when the construction of the railway is finished. The document was not given to Li Hongzhang, but kept in a top secret folder in the Department of Treasury of Russia." The 3,000,000 rubles were deposited into a dedicated fund of the Russo Chinese Bank. According to the recently exposed records of the Department of Treasury of the Russian Empire, Li Hongzhong eventually received 1,702,500 rubles of the three million, with receipts available at the Russian Winter Palace archive.

Public comments about Li were oriented towards negativee until CCTV production Towards the Republic was released in 2003. In this controversial TV series produced by mainland China's Central Television station, Li became a heroic image for the first time in mainland China. The series was later banned (mostly due to its extensive coverage on Dr.Sun Yat-sen's ideas and principles, which are advocated by Chinese nationalists in Taiwan, but not Chinese communists in mainland China).

Nevertheless, many historians and scholars consider Li a sophisticated politician, an adept diplomat and an industry pioneer in the later Qing Dynasty era of Chinese history. Though many of Li's signed treaties were considered unequal and humilating for China and he was for some decades named a traitor, more and more historical documents are being found showing some of Li's heroic episodes in his encounters with foreigners[citation needed].

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Zeng Guofan |

Acting Viceroy of Liangjiang 1865–1866 |

Succeeded by: Zeng Guofan |

| Preceded by: Guan Wen |

Viceroy of Huguang 1867–1870 |

Succeeded by: Li Hanzhang |

| Preceded by: Zeng Guofan |

Viceroy of Zhili and Minister of Beiyang (1st time) 1871—1895 |

Succeeded by: Wang Wenzhao |

| Preceded by: Tan Zhonglin |

Viceroy of Liangguang 1899─1900 |

Succeeded by: Tao Mo |

| Preceded by: Yu Lu |

Viceroy of Zhili and Minister of Beiyang (2nd time) 1900—1901 |

Succeeded by: Yuan Shikai |

See also

- Self-Strengthening Movement

- Military history of China

- Beiyang Army

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hummel, Arthur William, ed. Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (1644-1912). 2 vols. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1943.

- Liu, Kwang-ching. "The Confucian as Patriot and Pragmatist: Li Hung-Chang's Formative Years, 1823-1866." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 30 (1970): 5-45.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Antony Best, "Race, Monarchy, and the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902–1922," Social Science Japan Journal 2006 9(2):171-186