Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Lee Harvey Oswald" - New World

(credit Wiki) |

(cat, claim) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Claimed}} | ||

| + | {{epname}} | ||

{{Infobox Person | {{Infobox Person | ||

| name = Lee Harvey Oswald | | name = Lee Harvey Oswald | ||

| Line 285: | Line 287: | ||

[[tr:Lee Harvey Oswald]] | [[tr:Lee Harvey Oswald]] | ||

[[zh:李·奧斯瓦爾德]] | [[zh:李·奧斯瓦爾德]] | ||

| − | + | [[Category:History and biography]] | |

{{Credit|156934388}} | {{Credit|156934388}} | ||

Revision as of 15:31, 10 September 2007

| Lee Harvey Oswald | |

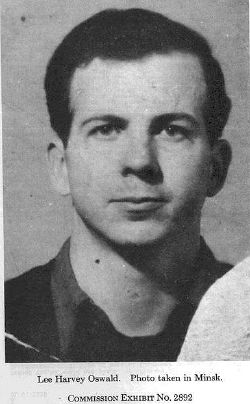

Lee Harvey Oswald during his time living in Minsk

| |

| Born | October 18 1939 New Orleans, Louisiana |

|---|---|

| Died | November 24 1963 (aged 24) Dallas, Texas |

Lee Harvey Oswald (October 18, 1939 – November 24, 1963) was, according to two United States government investigations, the assassin of U.S. President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963 in Dallas, Texas. A former Marine who defected to the Soviet Union and later returned, Oswald was arrested later that day on suspicion of killing the president and Dallas police officer J. D. Tippit. Oswald denied any responsibility for the murders. Two days later, before he could be brought to trial for the crimes, while being transferred under police custody from the police station to jail, Oswald was shot and killed by Jack Ruby on live television.

Although polls suggest most of the people in the United States agree Oswald had some role in the assassination, most believe he was part of a broader conspiracy and 7% believe he was not involved at all.[1]

Early life and Marine Corps service

Lee Harvey Oswald was born in New Orleans, Louisiana.[2] His father, Robert Edward Lee Oswald Sr., died shortly before he was born. His mother, Marguerite Claverie (1907–1981), largely raised Lee alone along with two older siblings: his brother Robert and his half-brother, John Pic, Marguerite's son from a previous marriage. Oswald did have a step-father for several years, and his mother sent him to an orphanage for several years when she was too poor to take care of him and his brothers. The family was Lutheran. His mother is said to have doted on him to excess. She has also been characterized as domineering and emotionally volatile, however. Lee's youth was plagued by extreme mobility; before the age of 18 Oswald had lived in 22 different residences. Because of the short-lived stay in each location, he had attended 12 different schools, mostly around New Orleans and Dallas, but also in New York City.

As a child Oswald was withdrawn and temperamental.[3] After moving in with John Pic (who had joined the US Coast Guard and was stationed in New York City), they were asked to leave due to an incident where Oswald allegedly threatened John Pic's wife with a knife, and struck his mother.[4] [5] Following charges of truancy, he had a three week court-ordered stay for psychiatric observation in a facility called "Youth House". Dr. Renatus Hartogs described Oswald as having a "Vivid fantasy life, turning around the topics of omnipotence and power, through which he tries to compensate for his present shortcomings and frustrations," and diagnosed the fourteen-year-old Oswald as having a "personality pattern disturbance with schizoid features and passive-aggressive tendencies" and recommended continued psychiatric intervention.[6] Oswald's behavior at school appeared to improve in his last months in New York.[7][8] In January 1954, his mother Marguerite decided to return to New Orleans with Lee, which prevented Lee from receiving the care the psychiatrist had recommended.[9] There was still an open question before a New York judge if he would be taken from the care of his mother to finish his schooling.[10]

Oswald left school after the ninth grade and never received a high school diploma. Throughout his life, he had trouble with spelling and writing coherently.[11] His letters, diary and other writings have led some to suggest he was dyslexic. Nonetheless he read voraciously and as a result sometimes asserted he was better educated than those around him. Around the age of fifteen, he became an ardent Marxist solely from reading about the topic. He wrote in his diary, "I was looking for a key to my environment, and then I discovered socialist literature. I had to dig for my books in the back dusty shelves of libraries."[12] At 16 he wrote to the Socialist Party of America, stating that he was a Marxist who had been studying socialist principles for "well over fifteen months," and asked for information about their youth league.[13]

Even as a Marxist, Oswald wished to join the US Marine Corps. He idolized his older brother Robert and wore Robert's US Marine ring. This relationship seems to have transcended any ideological conflict for Oswald, and enlisting in the Marines may have also been a way to escape from his overbearing mother.[14] He enlisted in the USMC in October 1956, a week after his 17th birthday.[15]

While in the Marines, Oswald was trained in the use of the M-1 rifle. Following that training, Oswald was tested in December of 1956, and obtained a score of 212, which was 2 points above the minimum for qualifications as a sharpshooter. In May 1959, on another range, Oswald scored 191, which was 1 point over the minimum for ranking as a marksman.[16]

Oswald was trained as a radar operator and assigned first to Marine Corps Air Station El Toro in Irvine, California,[17] then to Naval Air Facility Atsugi in Japan. Though Atsugi was a base for the U-2 spy planes that flew over the Soviet Union, there is no evidence Oswald was involved in that operation. Oswald's experience after joining with the Marine Corps was by all accounts unpleasant. Small and frail compared to the other Marines, he was nicknamed Ozzie Rabbit after a cartoon character. His shyness and Soviet sympathies alienated him from his fellow Marines. Ostracism only seemed to provoke him into being a more staunch and outspoken communist. For his steadfast beliefs, his nickname ultimately became Oswaldskovich. The Marine had subscribed to The Worker and taught himself rudimentary Russian. Oswald was tried at a court-martial twice: initially because of accidentally shooting himself in the elbow with an unauthorized handgun and again later for starting a fight with a sergeant he thought responsible for the punishment he received from his first court-martial. He was demoted from private first class to private, and briefly served time in the brig. He was not punished for yet another incident; while on sentry duty one night in the Philippines, he inexplicably fired his rifle into the jungle. By the end of his Marine career, Oswald was doing menial labor.

Life in the Soviet Union

In October 1959, Oswald emigrated to the Soviet Union. He was nineteen, and the trip was planned well in advance. Along with having taught himself rudimentary Russian, he had saved $1,500 of his Marine Corps salary,[18] got an early "hardship" discharge by (falsely) claiming he needed to care for his injured mother,[19] got a passport, and submitted several fictional applications to foreign universities in order to obtain a student visa (and possibly help avoid Marine Corps reserve duty).

After spending only three days with his mother in Fort Worth, he departed by ship from New Orleans on September 20, 1959, for the Soviet Union, first arriving in France, then England and eventually Finland as part of a package tour.[20] When he arrived in the Soviet Union and showed up unexpectedly at the US Embassy in Moscow, he said he wanted to renounce his U.S. citizenship.[21][22] When the Navy Department learned of this, it changed Oswald's Marine Corps discharge from "hardship/honorable" to "undesirable."[23]

Oswald told a reporter in Moscow, "For two years I've had it in my mind, don't form any attachments, because I knew I was going away. I was planning to divest myself of everything to do with the United States."[24] To another reporter he said, "I would not consider returning to the United States," and referred to the Soviet government as "my government."[25] His wish to remain in the Soviet Union was initially applauded by the Soviets, but although he had some technical knowledge acquired in the Marines they soon discovered he had little of real value to offer the Soviet Union and his application for Soviet residency was rejected.[26] In response, Oswald made a bloody but minor cut to his left wrist in his hotel room bathtub. After bandaging his superficial injury, the cautious Soviets kept him under psychiatric observation at the Botkin Hospital.[27][28] Although this attempt may have been no more than an attention-getting ruse, the Soviet government feared an international incident if he attempted something similar again.

Against the advice of the KGB, Oswald was allowed to remain in the Soviet Union. Although he had wanted to remain in Moscow and attend Moscow University, he was sent to Minsk, located in modern-day Belarus. He was given a job as a metal lathe operator at the Gorizont (Horizon) Electronics Factory in Minsk, a huge facility that produced radios and televisions along with military and space electronic components. He was given a rent-subsidized, fully furnished studio apartment in a prestigious building under Gorizont's administration and in addition to his factory pay received monetary subsidies from the Russian Red Cross Society (a Soviet organisation entirely separate from the international medical aid organization). This represented an idyllic existence by Soviet-era working-class standards.[29] Oswald was under constant surveillance by the KGB during his thirty-month stay in Minsk.[30] Oswald gradually grew bored with the limited recreation available in Minsk.[31] He wrote in his diary in January 1961: "I am starting to reconsider my desire about staying. The work is drab, the money I get has nowhere to be spent. No nightclubs or bowling alleys, no places of recreation except the trade union dances. I have had enough." Shortly thereafter, Oswald opened negotiations with the U.S. Embassy in Moscow looking toward his return to the United States.

At a dance in early 1961 Oswald met Marina Prusakova, a troubled 19-year-old pharmacology student from a broken family in Leningrad now living with her aunt and uncle in Minsk. While later reports described her uncle as a colonel in the KGB or MVD, he was actually a lumber industry expert in the MVD (Ministry of Interior) with a bureaucratic rank equivalent to colonel. Lee and Marina married on April 30, 1961, less than six weeks after they met. Their first child, June, was born in February 1962.

After nearly a year of paperwork and waiting, on June 1, 1962 the young family left the Soviet Union for the United States. Even before November 22, 1963, Oswald enjoyed a small measure of national notoriety in the U.S. press as an American who had defected to the U.S.S.R. and returned.[32]

Dallas

Back in the United States, the Oswalds settled in the Dallas/Fort Worth area, where his mother and brother lived, and Lee attempted to write his memoir and commentary on Soviet life, a small manuscript called The Collective. He soon gave up the idea but his search for literary feedback put him in touch with the area's close-knit community of anti-Communist Russian émigrés. While merely tolerating the belligerent and arrogant Lee Oswald, they sympathized with Marina, partly because she was in a foreign country with no knowledge of English (which her husband refused to teach her, saying he didn't want to forget Russian) and because Oswald had begun to beat her.[33] [34] Although they eventually abandoned Marina when she made no sign of leaving him,[35] Oswald had found an unlikely friend in the well-educated and worldly petroleum geologist George de Mohrenschildt,[36] who liked playing the provocateur[37] and enjoyed putting people off with his disagreeable and sullen Marxist friend.[38] A native Russian-speaker himself, de Mohrenschildt in the manuscript to his intended memoir (had he not died before its completion) wrote that Oswald spoke Russian "very well, with only a little accent."[39] Marina meanwhile befriended a married couple, Quaker Ruth Paine,[40] who was trying to learn Russian, and her husband Michael.

In Dallas in July 1962, Oswald got a job with the Leslie Welding Company but disliked the work and quit after three months. He then found a position in October 1962 at the graphic arts firm of Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall as a photoprint trainee. The company has been cited as doing classified work for the US government but this was limited to typesetting for maps and produced in a section to which Oswald had no access. He may have used photographic and typesetting equipment in the unsecured area to create falsified identification documents,[41] including some in the name of an alias he created, Alek James Hidell. His co-workers and supervisors eventually grew frustrated with his inefficiency, lack of precision, inattention, and rudeness to others, to the point where fights had threatened to break out.[42] He had also been seen reading a Russian publication, Krokodil (Russian: "Крокодил", "crocodile"), in the cafeteria. (Ironically, this magazine was largely a satire of the performance of the Soviet system, not of the West; by this time Oswald had long become dissatisfied with the U.S.S.R., as noted). On April 1, 1963, after six months of work, Oswald's supervisor terminated Oswald's employment at Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall.[43]

Attempted assassination of General Walker

Ten days after being fired, Oswald attempted to assassinate General Edwin Walker with the rifle shown in his backyard pose photos of March 31.[44]

General Edwin Walker was an outspoken anti-communist, segregationist and member of the John Birch Society who had been commanding officer of the Army's 24th Infantry Division based in West Germany under NATO supreme command until he was relieved of his command in 1961 by JFK for distributing right-wing literature to his troops. Walker resigned from the service and returned to his native Texas.

Walker ran in the six-person Democratic gubernatorial primary in 1962 but lost to John Connally, who went on to win the race. Walker became involved in the resistance to using federal troops to racially integrate the University of Mississippi that led to a riot on October 1, 1962, killing two people. He was arrested for insurrection, seditious conspiracy, and other charges. But a federal grand jury declined to indict Walker, and the charges were dropped on January 21, 1963.

Oswald considered Walker a "fascist" and the leader of a "fascist organization."[45] Five days after the front page news that Walker's charges had been dropped,[46] Oswald ordered a revolver by mail, using the alias "A.J. Hidell,"[47] and began talking about sending Marina and their daughter back to Russia.

In February 1963 the general was making news with an evangelist partner in an anti-Communist tour called Operation Midnight Ride. In a speech Walker made on March 5, reported in the Dallas Times Herald, he called on the United States military to "liquidate the scourge that has descended upon the island of Cuba." Seven days later, Oswald ordered by mail a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, using the alias "A. Hidell."[48]

While Walker was on tour, Oswald surveilled Walker's home on the weekend of March 9–10,[49] taking pictures of the house and nearby railroad tracks[50] which were later found among Oswald's belongings at the Paine home when they were searched after the Kennedy assassination (these photos were later matched to the same camera Marina used to take the backyard poses).[51] Though he did not leave specifics of his plans in writing, Oswald did leave a note in Russian for Marina with instructions for her to follow — should he be jailed in Dallas, or otherwise disappear.[52]

Oswald attempted the assassination on April 10, 1963. Walker was sitting at a desk in his dining room (working on his federal income tax returns) when Oswald fired at him from less than one hundred feet (30 m) away. Walker survived only because the bullet struck the wooden frame of the window, which deflected its path, but was injured in the forearm by bullet fragments.

The Dallas police had no suspects in the Walker shooting.[53] Oswald's involvement was not suspected until the note for Marina and some of the photos of Walker's house were found following the assassination of JFK, after which Marina Oswald told authorities about Oswald's attempt on Walker's life, which she said Oswald had told her about after the fact.[54] The bullet was too badly damaged to run conclusive ballistics studies on it, though neutron activation tests later showed that it was "extremely likely" that the Walker bullet was from the same cartridge manufacturer and for the same rifle make as the two bullets which later struck Kennedy.[55]

New Orleans

Oswald returned to New Orleans, arriving on the morning of April 25, 1963 looking for work. After Oswald got a job as a machinery greaser with the Reily Coffee Company in May, Marina was driven there by family friend Ruth Paine. Oswald was fired for inefficiency and dereliction of duty on July 19.

During this period, Oswald began to consider returning to the Soviet Union or going to Cuba.[56] He had Marina write to the Soviet Embassy in Washington, D.C. about the possibility of their returning to the Soviet Union.[57] His Marxist ideals became focused on Fidel Castro and Cuba and he soon became a vocal pro-Castro advocate. The Fair Play for Cuba Committee was a national organization and Oswald set out on his own initiative as a one-member New Orleans chapter, spending $22.73 on 1,000 flyers, 500 membership applications and 300 membership cards. He told Marina to sign the name "A.J. Hidell" as chapter president on one card.[58]

Most of Oswald's activities consisted of passing out flyers to passers-by on the street. He made a clumsy attempt to infiltrate anti-Castro exile groups and briefly met with a skeptical Carlos Bringuier, New Orleans delegate for the anti-Castro Cuban Student Directorate.[59] Several days later, on August 9, Bringuier and two friends confronted a man passing out pro-Castro handbills and realized that it was Oswald. During an ensuing scuffle all of them were arrested and Oswald spent the night in jail.

The arrest got news media attention and Oswald was interviewed afterwards. He was also filmed passing out flyers in front of the International Trade Mart with two "volunteers" he had hired for $2 at the unemployment office. Oswald's political work in New Orleans came to an end after a WDSU radio debate between Bringuier and Oswald arranged by journalist Bill Stuckey. Instead of discussing Cuba as he had successfully done during a previous radio program, Oswald was publicly confronted with the lies and omissions he had made concerning his life and background and became audibly upset.[60]

Oswald's five months in New Orleans were carefully scrutinized after the JFK assassination, most notably by New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison in his unsuccessful attempt to link Oswald to wealthy local businessman Clay Shaw, a former president of the city's International Trade Mart. Garrison's attempt to establish connections between the two included W. Guy Banister (a retired FBI agent and former New Orleans Police Assistant Superintendent turned private investigator and anti-communist) and Banister's friend David Ferrie, an anti-Castro activist and one-time employee of the attorney for Mafioso Carlos Marcello.

Ferrie and Oswald had been simultaneously members of the Civil Air Patrol in New Orleans in 1955, when Oswald was 15. Numerous witnesses have reported them attending the same CAP meetings,[61]and both appear in a CAP group photo.[62] The HSCA found no evidence they had any significant contact when Oswald was a teenager.[63]

The 1979 HSCA stated in its Report that it found evidence that Oswald, while living in New Orleans in the summer of 1963, had established contact with David Ferrie as well as with other non-Cubans of anti-Castro sentiments. [1] The Committee found "credible and significant" [2] the testimony of six witnesses who placed Oswald and Ferrie together in Clinton, Louisiana in September, 1963, where the Congress of Racial Equality was organizing a voter registration drive for black people in the area. Yet none of the six witnesses had reported this allegation to authorities after the assassination, and their original statements given four years later in 1967 for Jim Garrison's investigation contained numerous contradictions to their testimony at the Clay Shaw trial in 1969, and to their testimony to the Committee in 1978.[64]

Mexico

While Ruth Paine drove Marina back to Dallas in late September 1963, Oswald lingered in New Orleans for two more days waiting to collect a $33 unemployment check. He boarded a bus for Houston but instead of heading north to Dallas he took a bus southwest towards Laredo and the U.S.-Mexico border. Once in Mexico he hoped to continue on to Cuba, a plan he openly shared with other passengers on the bus.[65] Arriving in Mexico City, he completed a transit visa application at the Cuban Embassy,[66] claiming he wanted to visit the country on his way back to the Soviet Union. The Cubans insisted the Soviet Union would have to approve his journey to the USSR before he could get a Cuban visa, but he was unable to get speedy co-operation from the Soviet embassy.

After shuttling back and forth between consulates for five days, getting into a heated argument with the Cuban consul, making impassioned pleas to KGB agents, and coming under at least some CIA interest,[67] the Cuban consul told Oswald that "as far as [he] was concerned [he] would not give him a visa" and that "a person like him [Oswald] in place of aiding the Cuban Revolution, was doing it harm."[68] However, less than three weeks later, on October 18 the Cuban embassy in Mexico City finally approved the visa, and 11 days before the assassination Oswald wrote a letter to the Soviet embassy in Washington DC, which said, "Had I been able to reach the Soviet Embassy in Havana as planned, the embassy there would have had time to complete our business."[69][70]

Return to Dallas

Oswald left Mexico City on October 3, and returned by bus to Dallas, where he looked for employment. Through Ruth Paine he found a job filling book orders at the Texas School Book Depository, where he started work on October 16. During the week, he lived in a rooming house in Dallas, and spent the weekends with his wife at the Paine home in Irving, Texas, about 15 miles (24 km) from downtown Dallas. On October 20, the Oswalds' second daughter was born. During this period, the FBI was aware of Oswald's whereabouts in Texas, and agents from the Dallas office twice visited the Paine home in early November when Oswald was not present, hoping to get more information about Marina Oswald, whom the FBI suspected of being a Soviet agent.[71]

On November 16, a local newspaper reported that President Kennedy's motorcade would be going through downtown Dallas on November 22, "probably on Main Street" one block from the Texas School Book Depository, which it would have to pass to get onto the freeway to the President's luncheon site. This was confirmed by exact descriptions of the motorcade route published on November 19.[72] On Thursday, November 21, Oswald asked a co-worker for a ride to Irving, saying he had to pick up some curtain rods. The next morning, after leaving $170 and his wedding ring,[73] he returned with the co-worker to Dallas, carrying a long paper bag with him.[74]

Oswald was last seen by a co-worker alone on the sixth floor of the Depository about 35 minutes before the assassination.[75]

Assassination of JFK

The 1964 Warren Commission report on the John F. Kennedy assassination concluded that at 12:30 p.m. on November 22, 1963, Oswald shot Kennedy from a window on the sixth floor of the book depository warehouse as the President's motorcade passed through Dallas' Dealey Plaza.

Texas Governor John Connally was also seriously wounded along with assassination witness James Tague who received a minor facial injury. On the evening of November 22, in an impromptu news conference, Oswald denied shooting president Kennedy or officer J. D. Tippit.

Oswald's flight and the murder of Officer J. D. Tippit

According to the Warren Commission report, immediately after he shot President Kennedy, Oswald hid the rifle behind some boxes and descended via the Depository's rear stairwell. On the second floor he encountered Dallas police officer Marion Baker who had driven his motorcycle to the door of the Depository and sprinted up the stairs in search of the shooter. With Baker was Oswald's supervisor Roy Truly, who identified Oswald as an employee, which caused Baker, who had his pistol in hand, to let Oswald pass. Oswald bought a Coke from a vending machine in the second floor lunchroom, crossed the floor to the front staircase, descended and left the building through the front entrance on Elm Street, just before the police sealed the building off. He would be the only employee to leave early that day; his supervisor later noticed only Oswald missing,[76] and reported his name and address to the Dallas police in the building.[77]

At about 12:40 p.m. (CST), Oswald boarded a city bus by pounding on the door in the middle of a block, when heavy traffic had slowed the bus to a halt. On the bus was Oswald's former landlady, who recognized him.[78] About two blocks later, he requested a bus transfer from the driver and exited the bus.[79] He took a taxicab to a few blocks beyond his rooming house at 1026 N. Beckley Ave. He walked back to his rooming house at about 1:00 p.m., went into his room briefly, and came out zipping up a jacket. His housekeeper, Earlene Roberts testified that "he was walking pretty fast — he was all but running."[80] Oswald left the house and was last seen by Roberts standing by a bus stop across the street.[81]

He was next seen walking about eight-tenths of a mile away. Patrolman J. D. Tippit encountered Oswald near the corner of Patton Avenue and 10th Street, and pulled up to talk to him through his patrol car window.[82] Tippit then got out of his car and Oswald fired at the police officer with his .38 caliber revolver. Four of the shots hit Tippit, killing him, in view of two eyewitnesses.[83] Seven other witnesses heard the shots and saw the gunman flee the scene with the revolver in his hand. Three other witnesses identified Oswald as fleeing the scene.[84][85] Four cartridge cases were found at the scene by eyewitnesses. It was the unanimous testimony of expert witnesses before the Warren Commission that these used cartridge cases were fired from the revolver in Oswald's possession to the exclusion of all other weapons.[86]

A few minutes later, Oswald ducked into the entrance alcove of a shoe store to avoid passing police cars, then slipped into the nearby Texas Theater without paying (even though he had $13.87 in his pocket).[87] The shoe store's manager noticed Oswald and followed him into the theater where he alerted the ticket clerk, who phoned the police.

The police quickly arrived en masse and entered the theater as the lights were turned on. Officer M.N. McDonald approached Oswald sitting near the rear and ordered him to stand up. As Oswald said "Well, it is all over now" and appeared to raise his hands in surrender, he struck the officer. A scuffle ensued where McDonald reported that Oswald pulled the trigger on his revolver, but the hammer came down on the web of skin between the thumb and forefinger of the officer's hand, which prevented the revolver from firing.[88] Oswald was eventually subdued. As he was led past an angry group of people who had gathered outside the theater, Oswald shouted that he was a victim of police brutality.

Oswald was held on suspicion first as a suspect in the shooting of Officer Tippit and was questioned by Detective Jim Leavelle. Shortly afterward Oswald was also booked on suspicion of murdering both President Kennedy and Officer Tippit. By the end of the night he had been arraigned for both murders.[89]

While in custody, Oswald had an impromptu, face-to-face brush with reporters and photographers in the hallway of the police station. A reporter asked him, "Did you shoot the President?" and Oswald answered, "I have not been accused of that." The reporters answered that he had been. "In fact, I didn't even know about it until a reporter in the hall asked me that question," Oswald added. Later Oswald said to reporters, "I didn't shoot anyone," and "They're taking me in because of the fact that I lived in the Soviet Union. I'm just a patsy!"

Unedited footage of the impromptu face-to-face also shows Jack Ruby lingering amongst the reporters.[90]

Police interrogation

Oswald was interrogated several times during his two days of detention at Dallas Police Headquarters. He denied killing President Kennedy or Officer Tippit, denied owning a rifle, said two photographs of him holding a rifle and a pistol were fakes, denied knowing anything about the forged Selective Service card with the name "Alek J. Hidell" in his wallet, denied telling his co-worker he wanted a ride to Irving to get curtain rods for his apartment, and denied he had been seen carrying a long heavy package to work the following morning.[91]

Oswald's murder

At 11:21 am CST Sunday, November 24, while he was handcuffed to Detective Leavelle and as he was about to be taken to the Dallas County Jail, Oswald was shot and fatally wounded before live television cameras in the basement of Dallas police headquarters by Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub owner who had been distraught over the assassination.

Unconscious, Oswald was put into an ambulance and rushed to Parkland Memorial Hospital, the same hospital where JFK had died two days earlier. Doctors operated on Oswald, but Ruby's single bullet had severed major abdominal blood vessels, and the doctors were unable to repair the massive trauma. At 48 hours and 7 minutes after the President's death, Oswald was pronounced dead. After a full autopsy, Oswald's body[92] was returned to his family.

Oswald's grave is in Rose Hill Memorial Burial Park in Fort Worth.[93] The inexpensive coffin was provided at the expense of the state. The November 25th burial and funeral were paid for by Oswald's brother Robert. Reporters acted as pallbearers. When his mother died in 1981 she was buried next to Oswald with no headstone. Originally his headstone read Lee Harvey Oswald, but this marker was stolen and replaced with one which only reads Oswald. His wife Marina, who was sequestered by federal agents the day after the assassination and later released, married Kenneth Porter in 1965 and her two daughters June and Rachel took Porter's last name.

Investigations

- The Warren Commission created by President Lyndon B. Johnson on November 29, 1963 to investigate the assassination concluded that Oswald assassinated Kennedy and that he acted alone (also known as the Lone gunman theory). The proceedings of the commission were closed, but not secret, and about 3% of its files have yet to be released to the public, which has continued to provoke speculation among conspiracy theorists.[94]

- In 1968 The Ramsey Clark Panel met in Washington, DC to examine various photographs, X-ray films, documents, and other evidence pertaining to the death of President Kennedy. It concluded that President Kennedy was struck by two bullets fired from above and behind him, one of which traversed the base of the neck on the right side without striking bone and the other of which entered the skull from behind and destroyed its right side.[95]

- In 1979, an investigation by the House Select Committee on Assassinations, concluded that Oswald assassinated President Kennedy "probably...as the result of a conspiracy." The HSCA prepared an initial report concluding that Oswald acted alone until a Dictabelt recording purportedly of the assassination surfaced and the Committee revised their conclusion. This acoustic evidence has itself been called into question and many believe it is not a recording of the assassination at all.[96] The attorney for the House Select Committee on Assassinations, G. Robert Blakey, told ABC News that there were 20 people, at least, who heard a shot from the grassy knoll, and that the conclusion that a conspiracy existed in the assassination was established by both the witness testimony and acoustic evidence. In 2004, he expressed less confidence in the acoustic evidence.[97] Officer McLain, whose motorcycle the Dictabelt evidence comes from, has repeatedly stated that he was not yet in Dealey Plaza at the time of the assassination.[98] The HSCA was unable to identify the other gunman or the extent of the conspiracy. It also had insufficient evidence to identify any group responsible.

In 1982 a group of twelve scientists appointed by the National Academy of Sciences, led by Professor Norman Ramsey of Harvard, concluded that the acoustical evidence and the team behind its submission to the HSCA was 'seriously flawed', and has effectively been debunked.

Possible motives

The Warren Commission could not ascribe any one motive or group of motives to Oswald's actions:

It is apparent, however, that Oswald was moved by an overriding hostility to his environment. He does not appear to have been able to establish meaningful relationships with other people. He was perpetually discontented with the world around him. Long before the assassination he expressed his hatred for American society and acted in protest against it. Oswald's search for what he conceived to be the perfect society was doomed from the start. He sought for himself a place in history — a role as the "great man" who would be recognized as having been in advance of his times. His commitment to Marxism and communism appears to have been another important factor in his motivation. He also had demonstrated a capacity to act decisively and without regard to the consequences when such action would further his aims of the moment. Out of these and the many other factors which may have molded the character of Lee Harvey Oswald there emerged a man capable of assassinating President Kennedy.[99]

1981 exhumation

In October 1981 Oswald's body was exhumed at the behest of British writer Michael Eddowes, with Marina Oswald Porter's support. He sought to prove a thesis developed in a 1975 book, Khrushchev Killed Kennedy (re-published in 1976, in Britain as November 22: How They Killed Kennedy and in America a year later as The Oswald File).

Eddowes' theory was that during Oswald's stay in the Soviet Union he was replaced with a Soviet double named Alek, who was a member of a KGB assassination squad. Eddowes' claim is that it was this look-alike who killed Kennedy, and not Oswald. Eddowes's support for his thesis was a claim that the corpse buried in 1963 in the Shannon Rose Hill Memorial Park cemetery in Fort Worth, Texas did not have a scar that resulted from surgery conducted on Oswald years before.

When Oswald's body was exhumed it was found that the coffin had ruptured and was filled with water; leaving the body in an advanced state of decomposition with partial skeletonization. The examination positively identified Oswald's corpse through dental records, and also detected a mastoid scar from a childhood operation.[100] Contrary to reports, the skull of Oswald had been autopsied and this was confirmed at the exhumation.[101]

Assassination theories

Critics have not accepted the official government conclusions and have proposed a number of alternative theories which assert that Oswald conspired with others or Oswald was not involved at all and was framed. However, many of these theories contradict each other, and no single compelling alternative suspect or conspirator has emerged.

One government investigation, the HSCA, ruled out many of these theories but concluded that, while Oswald was the assassin, that Kennedy was "probably" killed as the result of a conspiracy. However, the HSCA report did not identify any probable co-conspirators and its conclusion has been criticised for its reliance upon acoustic evidence that has been called into question.

Mannlicher-Carcano rifle

'

In March 1963, Oswald used his alias "A. Hidell" (which he would later use for the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, and for which he was carrying an I.D. card when arrested after the Kennedy murder) to purchase the rifle later linked to the November 22, 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. The surplus Italian military rifle was purchased from Klein's Sporting Goods in Chicago, with a coupon taken from an ad in the February issue of American Rifleman. FBI and Treasury Department experts later matched the handwriting on the coupon and the envelope to Oswald. The rifle was purchased under "A. Hidell" but sent to a Dallas post office box rented by Oswald under his own name.

Backyard photos

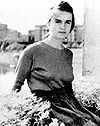

The "backyard photos," which were taken by Marina Oswald, probably around Sunday, March 31, 1963, show Oswald dressed all in black and holding two Marxist newspapers — The Militant and The Worker — in one hand, a rifle in the other, and carrying a pistol in its holster. The backyard photos were shot using a camera belonging to Oswald, an Imperial Reflex Duo-Lens 620. [102] When shown the pictures at Dallas Police headquarters after his arrest, Oswald insisted they were fakes.[103] However, Marina Oswald testified in 1964,[104] 1977,[105] and 1978,[106] and reaffirmed in 2000[107] that she took the photographs at Oswald's request. These photos were labelled CE 133-A and CE 133-B. CE 133-A shows the rifle in Oswald's left hand and newsletters in front of his chest in the other, while rifle is held with the right hand in CE 133-B. Oswald's mother testified that on the day after the assassination she and Marina destroyed another photograph with Oswald holding the rifle with both hands over his head, with "To my daughter June" written on it.[108]

The HSCA obtained another first generation print (from CE 133-A) on April 1, 1977 from the widow of George de Mohrenschildt. The words "Hunter of fascists — ha ha ha!" written in block Russian were on the back. Also in English were added in script: "To my friend George, Lee Oswald, 5/IV/63 [5 April 1963]"[109] Handwriting experts consulted by the HSCA concluded the English inscription and signature were written by Lee Oswald. After two original photos, one negative and one first-generation copy had been found, the Senate Intelligence Committee located (in 1976) a third photograph of Oswald with a backyard pose that was different (CE 133-C, with newspapers held in his right hand away from his body). A test photo by the Dallas Police in the identical pose was released with the Warren Commission evidence in 1964,[110] but it is not known why the photo itself was not publicly acknowledged until a print was found in 1975 amongst the belongings of deceased Dallas police officer Roscoe White.[111]

These photos have been subjected to rigorous analysis.[112] A panel of twenty-two photographic experts consulted by the HSCA examined the photographs and answered twenty-one points of contention raised by critics.[113] The panel concluded the photographs were genuine.[114] Marina Oswald has always maintained she took the photos herself, and the 1963 de Mohrenschildt print with Oswald's own signature clearly indicate they existed before the assassination. However, despite such evidence, some critics continue to contest the authenticity of the photographs, including Jack D. White in his testimony before the HSCA. [115]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Gary Langer, John F. Kennedy’s Assassination Leaves a Legacy of Suspicion (.pdf), ABC News, November 16, 2003

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 23, p. 799, CE 1963, Schedule showing known addresses of Lee Harvey Oswald from the time of his birth.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 7, page 378.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of John Edward Pic.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 22, p. 687, CE 1382, Interview with Mrs. John Edward Pic.

- ↑ Report of Renatus Hartogs, May 1, 1953 at Acorn.net.

- ↑ Carro Exhibit No. 1 Continued at Kennedy Assassination Home Page.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of John Carro.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 25, p. 123, CE 2223, Big Brothers of New York, Inc., Case file of Lee Harvey Oswald.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of Mrs. Marguerite Oswald.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapt. 7, p. 383.

- ↑ Twenty-Four Years, FRONTLINE, December 22, 2003.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, CE 2240, FBI transcript of letter from Lee Oswald to the Socialist Party of America, Oct. 3, 1956.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 7: Lee Harvey Oswald: Background and Possible Motives, Return to New Orleans and Joining the Marine Corps.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Marine Corps enlistment contract of Lee Harvey Oswald.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 4: The Assassin, Oswald's Marine Training.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Marine Corps service record of Lee Harvey Oswald.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, CE 1385, p. 10, Notes of interview of Lee Harvey Oswald conducted by Aline Mosby in Moscow in November 1959. Oswald: "When I was working in the middle of the night on guard duty, I would think how long it would be and how much money I would have to save. It would be like being out of prison. I saved about $1500." During Oswald's 2 years and 10 months of service in the Marine Corps he received $3,452.20, after all taxes, allotments and other deductions. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 26, p. 709, CE 3099, Certified military pay records for Lee Harvey Oswald for the period October 24, 1956, to September 11, 1959.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 19, Folsom Exhibit No. 1, p. 85, Request for Dependency Discharge.

- ↑ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, The Journey From USA to USSR at Russian Books

- ↑ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, Moscow Part 1 at Russian Books

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 18, p. 108, CE 912, Declaration of Lee Harvey Oswald, dated November 3, 1959, requesting that his U.S. citizenship be revoked.

- ↑ Warren Commissin Hearings, CE 780, Documents from Lee Harvey Oswald's Marine Corps file.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Notes of interview of Lee Harvey Oswald conducted by Aline Mosby in Moscow, November 1959.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Priscilla Johnson, "Oswald in Moscow," Harper's Magazine, April 1964, p. 47.

- ↑ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, How Could the KGB Not Be Interested in Oswald? at Russian Books

- ↑ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, Moscow Part 2 at Russian Books

- ↑ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, Moscow Part 3 at Russian Books

- ↑ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, Minsk Part 3 at Russian Books

- ↑ Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia, Minsk Part 2 at Russian Books

- ↑ http://www.archives.gov/research/jfk/warren-commission-report/chapter-7.html#defection

- ↑ "Brother Tries to Telephone, Halt Defector", Oakland Tribune November 2, 1959, p8. "U.S. Boy Prefers Russia", Syracuse Herald-Journal, December 11, 1959, p46. "Third Yank Said Quitting Soviet Union, San Mateo Times, June 8, 1962, p8.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report Chapter 7 — Relationship with Wife

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 11, p. 123, Affidavit of Alexander Kleinlerer: "Anna Meller, Mrs. Hall, George Bouhe, and the deMohrenschildts, and all that group had pity for Marina and her child. None of us cared for Oswald because of his political philosophy, his criticism of the United States, his apparent lack of interest in anyone but himself, and because of his treatment of Marina.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 11, p. 298, Testimony of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 2, p. 307, Testimony of Mrs. Katherine Ford. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 9, p. 252, Testimony of George de Mohrenschildt. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 9, p. 238, Testimony of George de Mohrenschildt. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 9, p. 266, Testiony of George de Mohrenschildt.

- ↑ George de Mohrenschildt, Staff Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations, 1979.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of George de Mohrenschildt:

- Mr. JENNER. Are you interested in debate?

- Mr. De MOHRENSCHILDT. Very much so; yes.

- Mr. JENNER. Are you inclined in order to facilitate debate to take any side of an argument as against somebody who seeks to support—

- Mr. De MOHRENSCHILDT. That is an unfortunate characteristic I have; yes.

- ↑ E.g., pp. 95–96, and 170–171 of De Mohrenschildt's memoir.

- ↑ George DeMorenschildt, "I'm a Patsy".

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 2, p. 435, Testmony of Ruth Hyde Paine.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 19, p. 288, Photograph of the face sides of a Selective Service System Notice of Classification. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 10, p. 201, Testimony of Dennis Hyman Ofstein.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of Dennis Hyman Ofstein: "I would say he didn't get along with people and that several people had words with him at times about the way he barged around the plant, and one of the fellows back in the photosetter department almost got in a fight with him one day, and I believe it was Mr. Graef that stepped in and broke it up before it got started…"

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of John G. Graef.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report p. 184-195

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 1, p. 16, Testimony of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald.

- ↑ "Judge Dismisses Walker Charges," Dallas Morning News, Jan. 22, 1963, sec. 1, p. 1.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 511, CE 135, Mail-order coupon in name of A.J. Hidell.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 17, p. 635, CE 773, Photograph of a mail order for a rifle in the name "A. Hidell," and the envelope in which the order was sent.

- ↑ Construction work seen in one of the photos was determined by the supervisor to have been in that state of completion on March 9–10. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 22, p. 585, CE 1351, FBI Report, Dallas, Tex., dated May 22, 1964, reflecting investigation concerning photographs of the residence of Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 4, CE 2, Group of photographs; Warren Commmission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 7, CE 5, Group of photographs, including a photograph of the home of Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker; Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 6, CE 4, Group of photographs.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 15, p. 692, Testimony of Lyndal L. Shaneyfelt.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 1, CE 1, Unsigned note to Marina Oswald.

- ↑ http://www.history-matters.com/archive/jfk/hsca/report/pdf/HSCA_Report_1A_LHO.pdf

- ↑ Warren Commission Report pp. 185

- ↑ House Select Committee on Assassinations, Testimony of Dr. Vincent P. Guinn:

- Mr. WOLF - In your professional opinion, Dr. Guinn, is the fragment removed from General Walker's house a fragment from a WCC [Western Cartridge Company] Mannlicher-Carcano bullet?

- Dr. GUINN - I would say that it is extremely likely that it is, because there are very few, very few other ammunitions that would be in this range. I don't know of any that are specifically this close as these numbers indicate, but somewhere near them there are a few others, but essentially this is in the range that is rather characteristic of WCC Mannlicher-Carcano bullet lead.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 1, p. 68, Testimony of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 17, p. 666, CE 781, Passport application of Lee Harvey Oswald, dated June 24, 1963. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 30, CE 13, Letter from Lee Harvey Oswald to the Russian Embassy, July 1, 1963. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 1, p. 47, Testimony of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 16, p. 10, CE 7, Translation of letter from Marina Oswald to the Russian Embassy, dated Feb. 17, 1963.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, p. 407.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 10, pp. 34–37, Testimony of Carlos Bringuier.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 21, p. 633, Stuckey Exhibit 3, Literal transcript of an audio-tape recording of a debate among Lee Harvey Oswald, Carlos Bringuier, and Ed Butler on August 21, 1963, Radio station WDSU, New Orleans.

- ↑ Summers, Anthony, The Kennedy Conspiracy 1998, ISBN 0-7515-1840-9

- ↑ More about the Ferrie Photo, FRONTLINE, November 20, 2003

- ↑ House Select Committee on Assassinations, Appendix to Hearings, vol. IX, pp. 103-115, Oswald, David Ferrie and the Civil Air Patrol.

- ↑ The HSCA did not have access to the 1967 statements. David Reitzes, Impeaching Clinton. Posner, pp. 143-147.

- ↑ Warren Commission hearings, volume 11, page 214-5. One theory by Warren Commission counsel David Belin was that Oswald's intention after assassinating President Kennedy was to board a 3:30 pm Greyhound bus to Monterrey, Mexico. He was heading in the direction of the departure point with $13.87 on him, just enough to pay for the ticket.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 25, p. 418, CE 2564, Cuban visa application of Lee Harvey Oswald, September 27, 1963.

- ↑ (undated) Oswald's Foreign Activities (Coleman and Slawson to Rankin) (page 94) at The Assassination Archives and Research Center

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, p. 413

- ↑ Oswald: Myth, Mystery, and Meaning, FRONTLINE, November 20, 2003

- ↑ HSCA Appendix to Hearings, vol. 8, p. 358, Letter from Lee Oswald to Embassy of the U.S.S.R., Washington, D.C., Nov. 9, 1963. CIA Report on Oswald's Stay in Mexico, Dec. 13, 1963. (page 19) at The Assassination Archives and Research Center.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, p. 739.

- ↑ Dallas Morning News, Nov. 19, 1963. Dallas Times Herald, Nov. 19, 1963, p. A-13.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. I, p. 72-73, Testimony of Marina Oswald.

- ↑ Magen Knuth, The Long Brown Bag.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of Charles Givens. An FBI report from Nov. 26, 1963 said that Depository employee Carolyn Arnold, as she exited the building to watch the motorcade, thought she caught a fleeting glimpse of Oswald standing in the first floor hallway of the building, a few minutes before 12:15. In 1978, she told author Anthony Summers that the FBI report misquoted her, and that she "clearly" saw Oswald sitting in the second floor lunchroom at 12:15 or slightly after. In either case, no other Depository employee reported seeing Oswald on the first or second floors between 12 noon and 12:30 p.m. (e.g., Mrs. Pauline Sanders, who left the second floor lunchroom at "approximately 12:20 p.m.," did not see Oswald anytime that day). The two Depository employees with whom Oswald said he ate lunch on the first floor both denied it.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of Roy Sansom Truly.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of J.W. Fritz.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. VI, p. 400, Testimony of Mary E. Bledsoe.

- ↑ Bus transfer (.gif) at Kennedy Assassination Home Page

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of Earlene Roberts.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 4: The Assassin, Oswald's Movements After Leaving Depository Building. Oswald's bus transfer, which he had transferred to the shirt he put on at his rooming house, and was found in his shirt pocket after his arrest, was good at only one stop in the Oak Cliff neighborhood, at Marsalis and Jefferson, three blocks from the Tippit shooting.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 19, p. 113, Barnes Exhibit A, Right side of Tippit squad car, showing open wing vent window.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 4: The Assassin, The Killing of Patrolman J.D. Tippit.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chaper 4: The Assassin, Description of Shooting.

- ↑ By the evening of November 22, five of them (Helen Markham, Barbara Jeanette Davis, Virginia Davis, Ted Callaway, Sam Guinyard) had identified Lee Harvey Oswald in police lineups as the man they saw. A sixth (William Scoggins) did so the next day. Three others (Harold Russell, Pat Patterson, Warren Reynolds) subsequently identified Oswald from a photograph. Two witnesses (Domingo Benavides, William Arthur Smith) testified that Oswald resembled the man they had seen. One witness (L.J. Lewis) felt he was too distant from the gunman to make a positive identification. Warren Commission Hearings, CE 1968, Location of Eyewitnesses to the Movements of Lee Harvey Oswald in the Vicinity of the Tippit Killing.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 3, pp. 466–473, Testimony of Cortlandt Cunningham. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 3, p. 511, Testimony of Jospeh D. Nicol.

- ↑ The films being shown were War Is Hell, narrated by Audie Murphy, and Cry of Battle.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, Testimony of M. N. McDonald.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 5: Detention and Death of Oswald, Chronology. Tippit murder affidavit: text, cover. Kennedy murder affidavit: text, cover.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 5: Detention and Death of Oswald, Activity of the Newsmen.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, pp. 180-182.

- ↑ Oswald's body after death

- ↑ Directions to Lee Harvey Oswald's Grave at Kennedy Assassination Home Page

- ↑ "Two misconceptions about the Warren Commission hearing need to be clarified...hearings were closed to the public unless the witness appearing before the Commission requested an open hearing. No witness except one...requested an open hearing...Second, although the hearings (except one) were conducted in private, they were not secret. In a secret hearing, the witness is instructed not to disclose his testimony to any third party, and the hearing testimony is not published for public consumption. The witnesses who appeared before the Commission were free to repeat what they said to anyone they pleased, and all of their testimony was subsequently published in the first fifteen volumes put out by the Warren Commission." (Bugliosi, p. 332)

- ↑ 1968 Panel Review of Photographs, X-Ray Films, Documents and Other Evidence Pertaining to the Fatal Wounding of President John E Kennedy on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas (.txt) at Kennedy Assassination Home Page

- ↑ Holland, Max. The JFK Lawyers' Conspiracy Published in The Nation on unknown date, reposted by George Mason University's History News Network 2006-02-06.

- ↑ http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/JFKblakey.htm.

- ↑ Greg Jaynes, The Scene of the Crime, Afterward.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 7: Unanswered Questions.

- ↑ W. Tracy Parnell, The Exhumation of Lee Harvey Oswald.

- ↑ W. Tracy Parnell, My Interview With Dr. Vincent J.M. Di Maio.

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 4: The Assassin, Photograph of Oswald With Rifle

- ↑ Warren Commission Report, Chapter 4: The Assassin, Denial of Rifle Ownership.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 1, p. 15, Testimony of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald.

- ↑ House Select Committee on Assassinations, Deposition of Marina Oswald Porter:

- Q. I want to mark these two photographs. On the back of the first one, which I would ask be marked JFK committee exhibit No. 1, it says in the bottom right-hand corner copy from the National Archives, records group No. 272, under that it says CE-133B. I will ask that be marked JFK exhibit No. 1. (The above referred to photograph was marked JFK committee exhibit No. 1 for identification.)

- Q. New, this second picture that I will ask to be marked says copy from the National Archives, record group No. 272, CE-133. I would ask that this be marked JFK committee exhibit No. 2. (The above referred to photograph was marked JFK committee exhibit No. 2 for identification.)

- By Mr. KLEIN:

- Q. I will show you those two photographs which are marked JFK exhibit No. 1 and exhibit No. 2, do you recognize those two photographs?

- A. I sure do. I have seen them many times.

- Q. What are they?

- A. That is the pictures that I took.

- ↑ House Select Committee on Assassinations Hearings, vol. 2, p. 239, Testimony of Marina Oswald Porter:

- Mr. McDONALD. Mrs. Porter, I have got two exhibits to show you, if the clerk would procure them from the representatives of the National Archives. We have two photographs to show you. They are Warren Commission Exhibits C-133-A and B, which have been given JFK Nos. F-378 and F-379. If the clerk would please hand them to you, and also if we could now have for display purposes JFK Exhibit F-179, which is a blowup of the two photographs placed in front of you. Mrs. Porter, do you recognize the photographs placed in front of you?

- Mrs. PORTER. Yes, I do.

- Mr. McDONALD. And how do you recognize them?

- Mrs. PORTER. That is the photograph that I made of Lee on his persistent request of taking a picture of him dressed like that with rifle.

- ↑ Marina Oswald Porter, interview with author Vincent Bugliosi and lawyer Jack Duffy, Dallas, Texas, Nov. 30, 2000, reported in Bugliosi, Reclaiming History, p. 794.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 1, p. 146, Testimony of Mrs. Marguerite Oswald.

- ↑ HSCA Appendix to Hearings, vol. 6, p. 151, Figure IV-21.

- ↑ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 17, p. 497, CE 712, Photographs taken by the Dallas Police Department on November 29, 1963, showing backyard of home on Neely Street in Dallas, where Oswald once lived.

- ↑ House Select Committee on Assassinations, Appendix to Hearings, p. 141, The Oswald Backyard Photographs.

- ↑ HSCA Appendix to Hearings, vol. 6, "The Oswald Backyard Photographs".

- ↑ House Select Committee on Assassinations Report Chapter VI

- ↑ id.

- ↑ House Select Committee on Assassinations, Hearings, Testimony of Jack D. White.

Further reading

- Vincent Bugliosi, Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Norton, 2007, 1632 p. ISBN 0393045250.

- Michael Eddowes, Khrushchev Killed Kennedy, self-published, (1975), paperback (republished as Nov. 22, How They Killed Kennedy, Neville Spearman (1976), hardback, ISBN 0-85978-019-8 and as The Oswald File, Potter (1977), hardcover, ISBN 0-517-53055-4)

- Robert J. Groden, The Search of Lee Harvey Oswald: A Comprehensive Photographic Record, New York: Penguin Studio Books, 1995. ISBN 0-670-85867-6

- Patricia Lambert, False Witness: The Real Story of Jim Garrison's Investigation and Oliver Stone's Film JFK, New York: M. Evans & Company, 1998, ISBN 0-87131-920-9

- David S. Lifton, Best Evidence: Disguise and Deception in the. Assassination of John F. Kennedy, Carroll & Graf Publishers, NYC, 1988, softcover, ISBN 0-88184-438-1

- Norman Mailer, Oswald's Tale: An American Mystery, New York: Ballantine Books, (1995) ISBN 0-345-40437-8

- Jim Marrs, Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy, Carroll & Graf Publishers, NYC, 1990, ISBN 0-88184-648-1

- Priscilla Johnson McMillan, Marina And Lee, New York: Haper & Row, 1977.

- Philip H. Melanson, Spy Saga: Lee Harvey Oswald And U. S. Intelligence, Praeger Publishing, (1990), ISBN 0-275-93571-X

- Dale K. Myers, With Malice: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, Oak Cliff Press, Inc., Milford, MI, 1998, ISBN 0-9662709-7-5

- John Newman, Oswald and the CIA, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers,1995. ISBN 0-7867-0131-5

- Oleg M. Nechiporenko, Passport to Assassination: The Never-Before Told Story of Lee Harvey Oswald by the KGB Colonel Who Knew Him, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1993, ISBN 1-559-72210-X

- Gerald Posner, Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK, Random House (1993), hardcover, ISBN 0-679-41825-3

- Anthony Summers, Conspiracy, Who Killed President Kennedy, Fontana (1980).

- Matthew Smith, JFK: Say Goodbye to America, Mainstream Publishing (2004).

External links

- Frontline: Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald?

- Lee Harvey Oswald's journey from Minsk to the US, travelling through Holland by Perry Vermeulen

- Kennedy Assassination Home Page by John McAdams

- The Unofficial JFK Assassination FAQ #19 by John Locke

- Lee Harvey Oswald: Lone Assassin or Patsy

- Lee Harvey Oswald Chronology

- Crime Library: Lee Harvey Oswald

- JFK Lancer Forum

- The President has been shot Website

- Lee Harvey Oswald In Russia

- Lee Harvey Oswald's Gravesite

- Lee Harvey Oswald's Camera - Imperial Reflex Duo-Lens - 620.

- The Last Words of Lee Harvey Oswald

- Mind Control: The Rosetta Stone of the JFK Assassination; Oswald as "Manchurian Candidate"

- Lee Harvey Oswald - Spartacus Educational website by John Simkin

- Lee Harvey Oswald Assassination Video on YouTube

- "LHO-63". Movie about Lee Harvey Oswald

Template:John F. Kennedy assassination

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Oswald, Lee Harvey |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Alleged assassin of President John F. Kennedy |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 18 1939 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Slidell, Louisiana |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 24 1963 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Dallas, Texas |

ar:لي هارفي اوزوالد

bs:Lee Harvey Oswald

bg:Лий Харви Осуалд

ca:Lee Harvey Oswald

da:Lee Harvey Oswald

de:Lee Harvey Oswald

et:Lee Harvey Oswald

el:Λη Χάρβεϊ Όσβαλντ

es:Lee Harvey Oswald

fr:Lee Harvey Oswald

ko:리 하비 오스월드

hr:Lee Harvey Oswald

id:Lee Harvey Oswald

it:Lee Harvey Oswald

he:לי הארווי אוסוואלד

hu:Lee Harvey Oswald

nl:Lee Harvey Oswald

ja:リー・ハーヴェイ・オズワルド

no:Lee Harvey Oswald

nn:Lee Harvey Oswald

pl:Lee Oswald

pt:Lee Harvey Oswald

ru:Освальд, Ли Харви

sr:Ли Харви Освалд

sh:Lee Harvey Oswald

fi:Lee Harvey Oswald

sv:Lee Harvey Oswald

tr:Lee Harvey Oswald

zh:李·奧斯瓦爾德

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.