Kon-Tiki

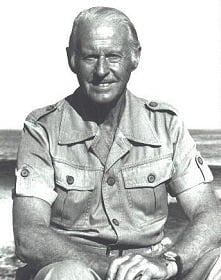

Kon-Tiki was the raft used by Norwegian explorer and writer Thor Heyerdahl in his 1947 expedition from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands. It was named after the Inca sun god, Viracocha, for whom "Kon-Tiki" was said to be an old name. Kon-Tiki is also the name of the popular book that Heyerdahl wrote about his adventures.

Heyerdahl believed that people from South America could have settled Polynesia in the South Pacific in Pre-Columbian times. His aim in mounting the Kon-Tiki expedition was to show, by using only the materials and technologies available to these people at the time, that there were no technical reasons to prevent them from having done so.

Heyerdahl and a small team went to Peru, where they constucted a balsa-wood raft out of balsa logs and other native materials in an indigenous style, as recorded in illustrations by Spanish conquistadores. This trip began on April 28, 1947. Accompanied by five companions, Heyerdahl sailed it for 101 days over 4,300 miles across the Pacific Ocean before smashing into the reef at Raroia in the Tuamotu Islands on August 7, 1947. The only modern equipment they had was a radio.

The book Kon-Tiki was a best-seller, and a documentary motion picture of the expedition won an Academy Award in 1951. The original Kon-Tiki raft is now on display in a museum by the same name in Oslo, Norway.

Construction

The main body of the raft was composed of nine balsa tree trunks up to 45 feet long, two feet in diameter, lashed together with one and a quarter inch of hemp ropes. Cross-pieces of balsa logs 18 feet long and one foot in diameter were lashed across the logs at three feet intervals to give lateral support. Pine splashboards clad the bow, and lengths of pine one inch thick and two feet long were wedged between the balsa logs and used as centerboards.

The main mast was made of lengths of mangrove wood lashed together to form a A-frame 29 feet high. Behind the main-mast was a cabin of plaited bamboo 14 feet long and eight feet wide was built about four to five feet high, and roofed with banana leaf thatch. At the stern was a 19-foot long steering oar of mangrove wood, with a blade of fir. The main sail was 15 by 18 feet on a yard of bamboo stems lashed together. Photographs also show a top-sail above the main sail, and also a mizzen-sail, mounted at the stern.

The raft was partially decked in split bamboo. No metal was used in the construction.

The Voyage

The Kon-Tiki left Callao, Peru, on the afternoon of April 28, 1947. It was initially towed 50 miles out to open water by the Fleet Tug Guardian Rios of the Peruvian Navy. She then sailed roughly west carried along on the Humboldt Current. Their first sight of land was the atoll of Puka-Puka on July 30. They made brief contact with the inhabitants of Angatau Island on August 4, but were unable to land safely. Three days later, on August 7, the raft struck a reef and was eventually beached on an uninhabited islet off Raroia Island in the Tuamotu group. They had travelled a distance of around 3,770 nautical miles in 101 days, at an average speed of 1.5 knots.

Stores

The Kon-Tiki carried 66 gallons of water in bamboo tubes. For food they took 200 coconuts, sweet potatoes, bottle gourds, and other assorted fruit and roots. The U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps of the US Army provided field rations, tinned food, and survival equipment. In return, the Kon-Tiki explorers reported on the quality, and utility of the provisions. They also caught plentiful numbers of fish, particularly flying fish, [[mahi-mahi], yellowfin tuna, and shark.

Crew

The Kon-Tiki was crewed by six men, all Norwegian except for Bengt Danielsson, who was from Sweden:

- Thor Heyerdahl was expedition leader.

- Erik Hesselberg was the navigator and artist. He painted the large Kon-Tiki figure on the raft's sail.

- Bengt Danielsson took on the role of steward, in charge of supplies and daily rations. Danielsson was a sociologist interested in human migration theory. He also served as translator, as he was the only member of the crew who spoke Spanish.

- Knut Haugland was a radio expert, decorated by the British in World War II for actions in the Norwegian, heavy-water sabotage that stalled Germany's plans to develop an atomic bomb.

- Torstein Raaby was also in charge of radio transmissions. He gained radio experience while hiding behind German lines during WWII, spying on the German battleship Tirpitz. His secret, radio transmissions eventually helped guide in Allied bombers to sink the ship.

- Herman Watzinger was an engineer whose area of expertise was in technical measurements. He recorded meteorological and hydrographical data while underway.

Communications

- Call Sign: LI2B

- Receiver: National NC-173

- Transmitter: unknown

- As an emergency backup they also carried a British Mark II transceiver originally produced by the SOE in 1942.

Marine life enountered

The Kon-Tiki explorers discovered the legendary snake mackerel (latin name Gempylus) and had a rare sighting of the whale shark. Heyerdahl had two experiences with the Gempylus. The first was at night, when the snake mackerel was washed into Torstein Raaby's sleeping bag; the second was also at night, when the Gempylus tried to attack the lantern. The whale shark, huge in size, hence its name, was so big that as it swam under the raft the explorers could see its huge, flat head on one side and its tail on the other. After about an hour of the whale shark circling the raft, a crew member rammed a harpoon into its skull. The whale shark simply broke the harpoon and swam away.

Anthropology

The Kon-Tiki adventure is often cited as a classic of "pseudoarchaeology," although its daring and inventive nature is still widely acclaimed. While the voyage was successfully demonstrated the seaworthiness of Heyerdahl's intentionally primitive raft, his theory that Polynesia was settled from South America did not gain acceptance by anthropologists. Physical and cultural evidence had long suggested that Polynesia was settled from west to east; migration having begun from the Asian mainland, not South America.

In the late 1990s, genetic testing found that the mitochondrial DNA of the Polynesians is more similar to people from southeast Asia than to people from South America, showing that their ancestors most likely came from Asia. It should be noted, however, that Heyerdahl claimed the people that settled Polynesia from South America were of a white race that was distinct from the South Americans and had been driven from their shores. Therefore, it would be expected that the DNA of the Polynesians would be dissimilar to that of South Americans.

According to Heyerdahl, some Polynesian legends say that Polynesia was originally inhabited by two peoples, the so-called long-eared and the short-eared. In a bloody war, all the long-eared peoples were eliminated and the short-eared people assumed sole control of Polynesia. Heyerdahl asserted that these extinct people were the ones who could have settled Polynesia from the Americas, not the current, short-eared inhabitants. However one of the problems with this argument is that traditions involving long-ears and short-ears are found only at Easter Island, and are unknown in the rest of Polynesia.

Heyerdahl further argues in his book American Indians in the Pacific that the current inhabitants of Polynesia did indeed migrate from an Asian source, but via an alternate route. He proposes that Polynesians travelled with the wind along the North Pacific current. These migrants then arrived in British Columbia. Heyerdahl points to the contemporary tribes of British Columbia, such as the Tlingit and Haida, as the descendants of these migrants. Again Heyerdahl notes the cultural and physical similarities between these British Columbian tribes, Polynesians, and the Old World source. Heyerdahl notes how simple it would have been for the British Columbians to travel to Hawaii and even onward to the greater Polynesia from their New World stepping-stone by way of wind and current patterns.

Heyerdahl's claims aside, there is no evidence that the Tlingit, Haida, or other British Columbian tribes have any special affinity with Polynesians. Linguistically, their morphologically complex languages are about as far from Austronesian and Polynesian languages as it is possible to be, and their cultures evince their undeniable links to the rest of the peoples of North America.

Anthropologist Robert C. Suggs included a chapter on "The Kon-Tiki Myth" in his book on Polynesia. He concludes:

- "The Kon-Tiki theory is about as plausible as the tales of Atlantis, Mu, and "Children of the Sun." Like most such theories it makes exciting light reading, but as an example of scientific method it fares quite poorly.[1]

Notes

- ↑ Robert C. Suggs, The Island Civilizations of Polynesia, New York: New American Library, p.224.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific in a Raft, Ballantine Books, 2000. ISBN 978-0345236234

- Kon-Tiki (DVD), Image Entertainment, 1951. ASIN B000055XNX

- Kon-Tiki Interactive (CD-Rom), Votager, 2006. ASIN B000KAL3XS

- Heyerdahl, Thor, & Lyon, F.H. Kon-Tiki, Rand McNally & Company, 1950. ASIN B000E3WM54

External links

- Kon-Tiki Museum

- National NC-173 receiver

- Quick Facts: Comparing the Two Rafts: Kon-Tiki and Tangaroa Azerbaijan International, Vol 14:4 (Winter 2006)

- Testing Heyerdahl's Theories about Kon-Tiki 60 Years Later: Tangaroa Pacific Voyage (Summer 2006) Azerbaijan International, Vol 14:4 (Winter 2006)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.