Goncharov, Ivan

| (17 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:Ivan Goncharov.jpg|thumb|right| | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}} |

| − | '''Ivan Alexandrovich Goncharov''' (June 18, 1812 – September 27, 1891; June 6 1812 – September 15 1891, O.S.) was a [[Russia]]n novelist best known as the author of ''Oblomov'' (1859). | + | {{epname|Goncharov, Ivan}} |

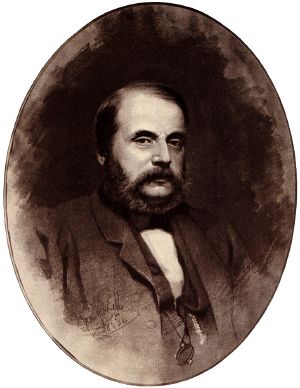

| − | + | [[Image:Ivan Goncharov.jpg|thumb|right|300px|''Ivan Goncharov'' by [[Ivan Kramskoi]]]] | |

| + | '''Ivan Alexandrovich Goncharov''' (June 18, 1812 – September 27, 1891; June 6, 1812 – September 15, 1891, O.S.) was a [[Russia]]n novelist best known as the author of ''Oblomov'' (1859). Oblomov is one of the most famous characters in all of nineteenth-century Russian literature. He is the most extreme representative of a type of character known as the "superfluous man." The superfluous man was informed by the position of the Russian aristocracy. In Western Europe the last vestiges of feudalism had been swept away, and a new era of [[democracy]] had begun. In Russia, the liberals had failed in the [[Decembrist Revolt]] to put any pressure on the government to reform. The revolt had had the opposite effect, feeding the arch-conservatism of [[Tsar Nicholas I]]. This led to a feeling of powerlessness among the intellectuals of the aristocracy, and increasingly to a rise of a more radical [[intelligentsia]], determined not to reform the old system to be replaced by more radical means. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| − | + | Goncharov was born in Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk); his father was a wealthy grain merchant. After graduating from [[Moscow]] University in 1834 Goncharov served for thirty years as a minor government official. | |

| − | In 1847, Goncharov's first novel, ''A Common Story'', was published; it dealt with the conflicts between the decadent Russian nobility and the rising merchant class. It was followed | + | In 1847, Goncharov's first novel, ''A Common Story'', was published; it dealt with the conflicts between the decadent Russian nobility and the rising merchant class. It was followed by ''Ivan Savvich Podzhabrin'' (1848), a naturalist psychological sketch. Between 1852 and 1855 Goncharov voyaged to [[England]], [[Africa]], [[Japan]], and back to Russia via Siberia as the secretary of Admiral Putyatin. His travelogue, a chronicle of the trip, ''The Frigate Pallada'' ''(The Frigate Pallas)'', was published in 1858 ("Pallada" is the Russian spelling of "Pallas"). |

| − | His wildly successful novel ''Oblomov'' was published the following year. The main character was compared to [[William Shakespeare|Shakespeare]]'s [[Hamlet]] who answers 'No!" to the question 'To be or not to be?" | + | His wildly successful novel ''Oblomov'' was published the following year. The main character was compared to [[William Shakespeare|Shakespeare]]'s [[Hamlet]] who answers 'No!" to the question 'To be or not to be?." [[Fyodor Dostoyevsky]], among others, considered Goncharov as a noteworthy author of high stature. |

In 1867 Goncharov retired from his post as a government censor and then published his last novel; ''The Precipice'' (1869) is the story of a rivalry between three men who seek the love of a woman of mystery. Goncharov also wrote short stories, critiques, essays and memoirs that were only published posthumously in 1919. He spent the rest of his days travelling in lonely and bitter recriminations because of the negative criticism some of his work received. Goncharov never married. He died in [[Saint Petersburg|St. Petersburg]]. | In 1867 Goncharov retired from his post as a government censor and then published his last novel; ''The Precipice'' (1869) is the story of a rivalry between three men who seek the love of a woman of mystery. Goncharov also wrote short stories, critiques, essays and memoirs that were only published posthumously in 1919. He spent the rest of his days travelling in lonely and bitter recriminations because of the negative criticism some of his work received. Goncharov never married. He died in [[Saint Petersburg|St. Petersburg]]. | ||

==Oblomov== | ==Oblomov== | ||

| − | + | ''Oblomov'' (first published: 1858) is Goncharov's best known [[novel]]. Oblomov is also the central character of the novel, often seen as the ultimate incarnation of the superfluous man, a stereotypical character in nineteenth-century Russian literature. There are numerous examples, such as [[Alexander Pushkin]]'s Eugene Onegin, [[Mikhail Lermontov]]'s Pechorin, [[Ivan Turgenev]]'s Rudin and [[Fyodor Dostoevsky]]'s Underground Man. The question of the superfluous man in nineteenth-century Russia is based on the persistence of the aristocracy into the modern era. Unlike in Western Europe, in which the last vestiges of [[feudalism]] had been swept away by the [[industrial revolution]] and a series of political revolutions, the aristocratic systems remained in place in Russia until the [[Russian Revolution of 1917]]. The aristocratic class became generally impoverished over the course of the nineteenth century, and were by and large becoming more irrelevant. Except for the civil service, opportunities did not exist for lower ranking men of talent. This type became disaffected. Thus, many talented individuals could not find a meaningful way to contribute to Russia's social development. In the early works, like those of Pushkin and Lermontov, they adopted the [[Lord Byron|Byronic]] pose of boredom. Later characters, like Turgenev's Rudin and Oblomov, seem genuinely paralyzed. In Dostoevsky, the problem becomes pathological. | |

Oblomov is one of the young, generous noblemen who seems incapable of making important decisions or undertaking any significant actions. Throughout the novel he rarely leaves his room or bed and famously fails to leave his bed for the first 150 pages of the novel. The novel was wildly popular when it came out in Russia and a number of its characters and devices have had an imprint on Russian culture and language. ''Oblomov'' has become a Russian word used to describe someone who exhibits the personality traits of sloth or inertia similar to the novel's main character. | Oblomov is one of the young, generous noblemen who seems incapable of making important decisions or undertaking any significant actions. Throughout the novel he rarely leaves his room or bed and famously fails to leave his bed for the first 150 pages of the novel. The novel was wildly popular when it came out in Russia and a number of its characters and devices have had an imprint on Russian culture and language. ''Oblomov'' has become a Russian word used to describe someone who exhibits the personality traits of sloth or inertia similar to the novel's main character. | ||

==Plot== | ==Plot== | ||

| − | <div style="float:right;image-width: | + | <div style="float:right;image-width:250px;margin:0 0 1em 1em;text-align:center;padding-left:24px"> |

| − | |||

{{spoiler}} | {{spoiler}} | ||

| − | The novel focuses on a midlife crisis for the main character, an upper middle class son of a member of Russia's nineteenth century merchant class. Oblomov's most distinguishing characteristic is his slothful attitude towards life. While a common negative characteristic, Oblomov raises this trait to an art form, conducting his little daily business apathetically from his bed. While clearly satirical, the novel also seriously examines many critical issues that faced | + | The novel focuses on a midlife crisis for the main character, an upper middle class son of a member of Russia's nineteenth-century merchant class. Oblomov's most distinguishing characteristic is his slothful attitude towards life. While a common negative characteristic, Oblomov raises this trait to an art form, conducting his little daily business apathetically from his bed. While clearly satirical, the novel also seriously examines many critical issues that faced Russian society in the nineteenth century. Some of these problems included the uselessness of landowners and gentry in a feudal society that did not encourage innovation or reform, the complex relations between members of different classes of society such as Oblomov's relationship with his servant Zakhar, and courtship and matrimony by the elite. |

| − | An excerpt from Oblomov's morning (from the beginning of the novel): | + | An excerpt from Oblomov's indolent morning (from the beginning of the novel): |

:''Therefore he did as he had decided; and when the tea had been consumed he raised himself upon his elbow and arrived within an ace of getting out of bed. In fact, glancing at his slippers, he even began to extend a foot in their direction, but presently withdrew it.'' | :''Therefore he did as he had decided; and when the tea had been consumed he raised himself upon his elbow and arrived within an ace of getting out of bed. In fact, glancing at his slippers, he even began to extend a foot in their direction, but presently withdrew it.'' | ||

| − | :''Half-past ten struck, and Oblomov gave himself a shake. | + | :''Half-past ten struck, and Oblomov gave himself a shake. "What is the matter?," he said vexedly. "In all conscience 'tis time that I were doing something! Would I could make up my mind to—to—" He broke off with a shout of "Zakhar!" whereupon there entered an elderly man in a grey suit and brass buttons—a man who sported beneath a perfectly bald pate a pair of long, bushy, grizzled whiskers that would have sufficed to fit out three ordinary men with beards. His clothes, it is true, were cut according to a country pattern, but he cherished them as a faint reminder of his former livery, as the one surviving token of the dignity of the house of Oblomov. The house of Oblomov was one which had once been wealthy and distinguished, but which, of late years, had undergone impoverishment and diminution, until finally it had become lost among a crowd of noble houses of more recent creation.'' |

:''For a few moments Oblomov remained too plunged in thought to notice Zakhar's presence; but at length the valet coughed.'' | :''For a few moments Oblomov remained too plunged in thought to notice Zakhar's presence; but at length the valet coughed.'' | ||

| Line 36: | Line 37: | ||

:''"You called me just now, barin?"'' | :''"You called me just now, barin?"'' | ||

| − | :''"I called you, you say? | + | :''"I called you, you say? Well, I cannot remember why I did so. Return to your room until I have remembered."'' |

Oblomov spends the first part of the book in bed or lying on his sofa. He receives a letter from the manager of his country estate explaining that the financial situation is deteriorating and that he must visit the estate to make some major decisions, but Oblomov can barely leave his bedroom, much less journey a thousand miles into the country. | Oblomov spends the first part of the book in bed or lying on his sofa. He receives a letter from the manager of his country estate explaining that the financial situation is deteriorating and that he must visit the estate to make some major decisions, but Oblomov can barely leave his bedroom, much less journey a thousand miles into the country. | ||

| − | A flashback reveals a good deal of why Oblomov is so slothful; the reader sees Oblomov's upbringing in the country village of Oblomovka. He is spoiled rotten and never required to work or perform household duties, and he is constantly pulled from school for vacations and trips or for trivial reasons. In contrast, his friend Andrey Stoltz, born to a German father and a Russian mother, is raised in a strict, disciplined environment, reflecting Goncharov's own view of the | + | A flashback reveals a good deal of why Oblomov is so slothful; the reader sees Oblomov's upbringing in the country village of Oblomovka. He is spoiled rotten and never required to work or perform household duties, and he is constantly pulled from school for vacations and trips or for trivial reasons. In contrast, his friend Andrey Stoltz, born to a German father and a Russian mother, is raised in a strict, disciplined environment, reflecting Goncharov's own view of the [[Europe]]an mentality as dedicated and hard-working. |

As the story develops, Stoltz introduces Oblomov to a young woman, Olga, and the two fall in love. However, his apathy and fear of moving forward are too great, and she calls off their engagement when it is clear that he will keep delaying their wedding to avoid having to take basic steps like putting his affairs in order. | As the story develops, Stoltz introduces Oblomov to a young woman, Olga, and the two fall in love. However, his apathy and fear of moving forward are too great, and she calls off their engagement when it is clear that he will keep delaying their wedding to avoid having to take basic steps like putting his affairs in order. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

During this period, Oblomov is swindled repeatedly by his "friend" Taranteyev and his landlord, and Stoltz has to undo the damage each time. The last time, Oblomov ends up living in penury because Taranteyev and the landlord are blackmailing him out of all of his income from the country estate, which lasts for over a year before Stoltz discovers the situation and reports the landlord to his supervisor. | During this period, Oblomov is swindled repeatedly by his "friend" Taranteyev and his landlord, and Stoltz has to undo the damage each time. The last time, Oblomov ends up living in penury because Taranteyev and the landlord are blackmailing him out of all of his income from the country estate, which lasts for over a year before Stoltz discovers the situation and reports the landlord to his supervisor. | ||

| Line 67: | Line 54: | ||

Goncharov's work added new words to the Russian lexicon, including "Oblomovism," a sort of fatalistic laziness that was said to be part of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avos the Russian character]. The novel also uses the term "Oblomovitis" to describe the disease that kills Oblomov. | Goncharov's work added new words to the Russian lexicon, including "Oblomovism," a sort of fatalistic laziness that was said to be part of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avos the Russian character]. The novel also uses the term "Oblomovitis" to describe the disease that kills Oblomov. | ||

| − | The term Oblomovism appeared in a speech given by [[Vladimir | + | The term Oblomovism appeared in a speech given by [[Vladimir Lenin]] in 1922, where he says that |

| − | :''Russia has made three revolutions, and still the Oblomovs have remained ... and he must be washed, cleaned, pulled about, and flogged for a long time before any kind of sense will emerge.'' | + | :''Russia has made three revolutions, and still the Oblomovs have remained...and he must be washed, cleaned, pulled about, and flogged for a long time before any kind of sense will emerge.'' |

==Screen adaptations== | ==Screen adaptations== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ''Oblomov'' was adapted to the cinema screen in the Soviet Union by famed director, Nikita Mikhalkov, in 1981 (145 minutes). The Cast and Crew: Actors—Oleg Tabakov as Oblomov, Andrei Popov as Zakhar, Elena Solovei as Olga and Yuri Bogatyrev as Andrei; cinematography by Pavel Lebechev; screenplay by Mikhailkov and Aleksander Adabashyan; music by Eduard Artemyev; produced by Mosfilm Studio (Moscow). | |

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | *Ehre, Milton. ''Oblomov and his creator; the life and art of Ivan Goncharov''. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1974. ISBN 0691062455 | ||

| + | *Lyngstad, Sverre and Alexandra. ''Ivan Goncharov''. MacMillan Publishing Company, 1984. ISBN 0805723803 | ||

| + | *Setchkarev, Vsevolod. ''Ivan Goncharov; his life and his works''. Würzburg, Jal-Verlag, 1974. ISBN 3777800910 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved March 10, 2018. | ||

| + | |||

* [http://www.oblomovka.com/eldritch/iag/oblomov.htm ''Oblomov''] Public Domain translation from 1915 | * [http://www.oblomovka.com/eldritch/iag/oblomov.htm ''Oblomov''] Public Domain translation from 1915 | ||

* [http://lib.ru/LITRA/GONCHAROW/oblomov.txt ''Oblomov''] The original Russian text | * [http://lib.ru/LITRA/GONCHAROW/oblomov.txt ''Oblomov''] The original Russian text | ||

*[http://ilibrary.ru/text/475/ Full text of ''Oblomov'' in the original Russian] at Alexei Komarov's Internet Library | *[http://ilibrary.ru/text/475/ Full text of ''Oblomov'' in the original Russian] at Alexei Komarov's Internet Library | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | [[ | + | [[Category:Biography]] |

| − | {{credit2| | + | [[Category:Writers and poets]] |

| + | {{credit2|Ivan_Goncharov|53822958|Oblomov|67502745}} | ||

Latest revision as of 06:35, 11 March 2024

Ivan Alexandrovich Goncharov (June 18, 1812 – September 27, 1891; June 6, 1812 – September 15, 1891, O.S.) was a Russian novelist best known as the author of Oblomov (1859). Oblomov is one of the most famous characters in all of nineteenth-century Russian literature. He is the most extreme representative of a type of character known as the "superfluous man." The superfluous man was informed by the position of the Russian aristocracy. In Western Europe the last vestiges of feudalism had been swept away, and a new era of democracy had begun. In Russia, the liberals had failed in the Decembrist Revolt to put any pressure on the government to reform. The revolt had had the opposite effect, feeding the arch-conservatism of Tsar Nicholas I. This led to a feeling of powerlessness among the intellectuals of the aristocracy, and increasingly to a rise of a more radical intelligentsia, determined not to reform the old system to be replaced by more radical means.

Biography

Goncharov was born in Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk); his father was a wealthy grain merchant. After graduating from Moscow University in 1834 Goncharov served for thirty years as a minor government official.

In 1847, Goncharov's first novel, A Common Story, was published; it dealt with the conflicts between the decadent Russian nobility and the rising merchant class. It was followed by Ivan Savvich Podzhabrin (1848), a naturalist psychological sketch. Between 1852 and 1855 Goncharov voyaged to England, Africa, Japan, and back to Russia via Siberia as the secretary of Admiral Putyatin. His travelogue, a chronicle of the trip, The Frigate Pallada (The Frigate Pallas), was published in 1858 ("Pallada" is the Russian spelling of "Pallas").

His wildly successful novel Oblomov was published the following year. The main character was compared to Shakespeare's Hamlet who answers 'No!" to the question 'To be or not to be?." Fyodor Dostoyevsky, among others, considered Goncharov as a noteworthy author of high stature.

In 1867 Goncharov retired from his post as a government censor and then published his last novel; The Precipice (1869) is the story of a rivalry between three men who seek the love of a woman of mystery. Goncharov also wrote short stories, critiques, essays and memoirs that were only published posthumously in 1919. He spent the rest of his days travelling in lonely and bitter recriminations because of the negative criticism some of his work received. Goncharov never married. He died in St. Petersburg.

Oblomov

Oblomov (first published: 1858) is Goncharov's best known novel. Oblomov is also the central character of the novel, often seen as the ultimate incarnation of the superfluous man, a stereotypical character in nineteenth-century Russian literature. There are numerous examples, such as Alexander Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, Mikhail Lermontov's Pechorin, Ivan Turgenev's Rudin and Fyodor Dostoevsky's Underground Man. The question of the superfluous man in nineteenth-century Russia is based on the persistence of the aristocracy into the modern era. Unlike in Western Europe, in which the last vestiges of feudalism had been swept away by the industrial revolution and a series of political revolutions, the aristocratic systems remained in place in Russia until the Russian Revolution of 1917. The aristocratic class became generally impoverished over the course of the nineteenth century, and were by and large becoming more irrelevant. Except for the civil service, opportunities did not exist for lower ranking men of talent. This type became disaffected. Thus, many talented individuals could not find a meaningful way to contribute to Russia's social development. In the early works, like those of Pushkin and Lermontov, they adopted the Byronic pose of boredom. Later characters, like Turgenev's Rudin and Oblomov, seem genuinely paralyzed. In Dostoevsky, the problem becomes pathological.

Oblomov is one of the young, generous noblemen who seems incapable of making important decisions or undertaking any significant actions. Throughout the novel he rarely leaves his room or bed and famously fails to leave his bed for the first 150 pages of the novel. The novel was wildly popular when it came out in Russia and a number of its characters and devices have had an imprint on Russian culture and language. Oblomov has become a Russian word used to describe someone who exhibits the personality traits of sloth or inertia similar to the novel's main character.

Plot

The novel focuses on a midlife crisis for the main character, an upper middle class son of a member of Russia's nineteenth-century merchant class. Oblomov's most distinguishing characteristic is his slothful attitude towards life. While a common negative characteristic, Oblomov raises this trait to an art form, conducting his little daily business apathetically from his bed. While clearly satirical, the novel also seriously examines many critical issues that faced Russian society in the nineteenth century. Some of these problems included the uselessness of landowners and gentry in a feudal society that did not encourage innovation or reform, the complex relations between members of different classes of society such as Oblomov's relationship with his servant Zakhar, and courtship and matrimony by the elite.

An excerpt from Oblomov's indolent morning (from the beginning of the novel):

- Therefore he did as he had decided; and when the tea had been consumed he raised himself upon his elbow and arrived within an ace of getting out of bed. In fact, glancing at his slippers, he even began to extend a foot in their direction, but presently withdrew it.

- Half-past ten struck, and Oblomov gave himself a shake. "What is the matter?," he said vexedly. "In all conscience 'tis time that I were doing something! Would I could make up my mind to—to—" He broke off with a shout of "Zakhar!" whereupon there entered an elderly man in a grey suit and brass buttons—a man who sported beneath a perfectly bald pate a pair of long, bushy, grizzled whiskers that would have sufficed to fit out three ordinary men with beards. His clothes, it is true, were cut according to a country pattern, but he cherished them as a faint reminder of his former livery, as the one surviving token of the dignity of the house of Oblomov. The house of Oblomov was one which had once been wealthy and distinguished, but which, of late years, had undergone impoverishment and diminution, until finally it had become lost among a crowd of noble houses of more recent creation.

- For a few moments Oblomov remained too plunged in thought to notice Zakhar's presence; but at length the valet coughed.

- "What do you want?" Oblomov inquired.

- "You called me just now, barin?"

- "I called you, you say? Well, I cannot remember why I did so. Return to your room until I have remembered."

Oblomov spends the first part of the book in bed or lying on his sofa. He receives a letter from the manager of his country estate explaining that the financial situation is deteriorating and that he must visit the estate to make some major decisions, but Oblomov can barely leave his bedroom, much less journey a thousand miles into the country.

A flashback reveals a good deal of why Oblomov is so slothful; the reader sees Oblomov's upbringing in the country village of Oblomovka. He is spoiled rotten and never required to work or perform household duties, and he is constantly pulled from school for vacations and trips or for trivial reasons. In contrast, his friend Andrey Stoltz, born to a German father and a Russian mother, is raised in a strict, disciplined environment, reflecting Goncharov's own view of the European mentality as dedicated and hard-working.

As the story develops, Stoltz introduces Oblomov to a young woman, Olga, and the two fall in love. However, his apathy and fear of moving forward are too great, and she calls off their engagement when it is clear that he will keep delaying their wedding to avoid having to take basic steps like putting his affairs in order.

During this period, Oblomov is swindled repeatedly by his "friend" Taranteyev and his landlord, and Stoltz has to undo the damage each time. The last time, Oblomov ends up living in penury because Taranteyev and the landlord are blackmailing him out of all of his income from the country estate, which lasts for over a year before Stoltz discovers the situation and reports the landlord to his supervisor.

Olga leaves Russia and visits Paris, where she bumps into Stoltz on the street. The two strike up a romance and end up marrying.

It must be noted, however, that not even Oblomov could go through life without at least one moment of self-possession and purpose. When Taranteyev's behavior at last reaches insufferable lows, Oblomov confronts him, slaps him around a bit and finally kicks him out of the house, in a scene in which all the noble traits that his social class was supposed to symbolize shine through his then worn out being. Oblomov ends up marrying Agafia Pshenitsina, a widow and the sister of Oblomov's crooked landlord. They have a son named Andrey, and when Oblomov dies, his friend Stoltz adopts the boy. Oblomov spends the rest of his life in a second Oblomovka, being taken care of by Agafia Pshenitsina like he used to be as a kid. She can prepare many a succulent meal, and makes sure that Oblomov don't have a single worrisome thought. Sometime before his death he had been visited by Stoltz, who had promised to his wife a last attempt at bringing Oblomov back to the world, but without success. By then Oblomov had already accepted his fate, and during the conversation he mentions "Oblomovitis" as the real cause of his demise. Oblomov's final days are not without melancholy, but then again nobody's final days are supposed to be light affairs. In the end he just slows down as a body and dies sleeping, his old servant then becoming a beggar.

Influence

Goncharov's work added new words to the Russian lexicon, including "Oblomovism," a sort of fatalistic laziness that was said to be part of the Russian character. The novel also uses the term "Oblomovitis" to describe the disease that kills Oblomov.

The term Oblomovism appeared in a speech given by Vladimir Lenin in 1922, where he says that

- Russia has made three revolutions, and still the Oblomovs have remained...and he must be washed, cleaned, pulled about, and flogged for a long time before any kind of sense will emerge.

Screen adaptations

Oblomov was adapted to the cinema screen in the Soviet Union by famed director, Nikita Mikhalkov, in 1981 (145 minutes). The Cast and Crew: Actors—Oleg Tabakov as Oblomov, Andrei Popov as Zakhar, Elena Solovei as Olga and Yuri Bogatyrev as Andrei; cinematography by Pavel Lebechev; screenplay by Mikhailkov and Aleksander Adabashyan; music by Eduard Artemyev; produced by Mosfilm Studio (Moscow).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ehre, Milton. Oblomov and his creator; the life and art of Ivan Goncharov. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1974. ISBN 0691062455

- Lyngstad, Sverre and Alexandra. Ivan Goncharov. MacMillan Publishing Company, 1984. ISBN 0805723803

- Setchkarev, Vsevolod. Ivan Goncharov; his life and his works. Würzburg, Jal-Verlag, 1974. ISBN 3777800910

External links

All links retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Oblomov Public Domain translation from 1915

- Oblomov The original Russian text

- Full text of Oblomov in the original Russian at Alexei Komarov's Internet Library

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.