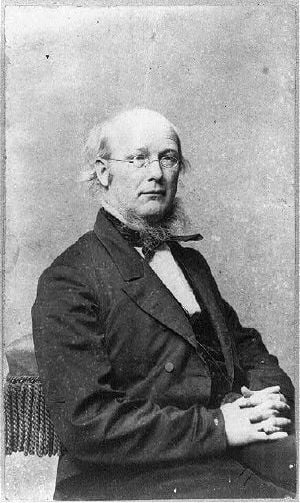

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was a newspaper editor, reformer, and politician. His New York Tribune was one of America's most influential sources of news in the mid-nineteenth century. Greeley used the paper to promote the Whig and Republican parties, as well as abolitionism and other reforms. Greeley had political ambition, and served briefly as a congressman. However he never achieved office despite numerous attempts, even running for president in 1872, to a crushing defeat. Under Greeley's direction, the New York Tribune exemplified high standards in news gathering, writing, and morality. Although criticized for using the paper to support his political aims, Greeley's work was a major influence in raising the standard of journalism away from popular sensationalism to a more educational, values-oriented approach.

Life

Horace Greeley was born on February 3, 1811, in Amherst, New Hampshire, the son of a poor farmer. He declined a scholarship to Phillips Exeter Academy and left school at age 14. He then apprenticed as a printer in Vermont, moving to New York City in 1831, at age 20.[1] Greeley served a stint as editor of the New Yorker in 1834.[2]

In 1836, Greeley married Mary Cheney, a schoolteacher and sometime suffragette. Greeley would sleep in a boarding house when in New York City after working 18 hour days at the newspaper, leaving little time for his family.[3] Of their seven children, only two daughters reached maturity.

In 1841, Greeley founded the New York Tribune, which he edited until his death.

Crusading against the corruption of Ulysses S. Grant's Republican administration, Greeley was the presidential candidate in 1872 of a new Liberal Republican Party, but lost in a landslide despite having the additional support of the Democratic Party.

Not long after the election of 1872, Greeley's wife died. Suffering an emotional breakdown after the death of his wife and the loss of the presidential election, Greeley checked into a private sanitarium. He died a few weeks later, on November 29, 1872. Greeley had requested a simple funeral, but his daughters ignored this request and arranged a grand affair. He was buried in New York's Green-Wood Cemetery.

The New York Tribune

Greeley established the New York Tribune in 1841. It was long considered one of the leading newspapers in the United States. It soon was a success as the leading Whig paper in the metropolis; its weekly edition reached tens of thousands of subscribers across the country. Greeley was editor of the Tribune for the rest of his life, using it as a platform for advocacy of all his causes.

The Tribune was created by Greeley with the hopes of providing a straightforward, trustworthy media source in an era when newspapers such as the New York Sun and New York Herald thrived on sensationalism. Although considered the least partisan of the leading newspapers, the Tribune did reflect some of Horace Greeley's idealist views. As historian Allan Nevins explained:

The Tribune set a new standard in American journalism by its combination of energy in news gathering with good taste, high moral standards, and intellectual appeal. Police reports, scandals, dubious medical advertisements, and flippant personalities were barred from its pages; the editorials were vigorous but usually temperate; the political news was the most exact in the city; book reviews and book-extracts were numerous; and as an inveterate lecturer Greeley gave generous space to lectures. The paper appealed to substantial and thoughtful people. (Nevins in Dictionary of American Biography 1931)

What made the Tribune such a success was that Greeley was an excellent judge of newsworthiness and quality of reporting. It contained extensive news stories, very well written by brilliant reporters, together with feature articles by fine writers.

During the American Civil War (1861–1865) the Tribune was a radical Republican newspaper, which supported abolition and subjection of the Confederacy instead of negotiated peace. During the first few months of the war, the Tribune's "on to Richmond" slogan pressured Union general Irvin McDowell into advancing on Richmond before his army was ready, resulting in the disaster of the First Battle of Manassas on July 21, 1861. After the failure of the Peninsular Campaign in the spring of 1862, the Tribune pressured President Abraham Lincoln into installing John Pope as commander of the Army of Virginia.

Following Greeley's defeat for the presidency of the United States in 1872, Whitelaw Reid, owner of the New York Herald, assumed control of the Tribune. Under Reid's son, Ogden Mills Reid, the paper acquired the New York Herald to form the New York Herald Tribune, which continued to be run by Reid until his death in 1947. Greeley was bitter about the takeover of his Tribune, to the extent of accusing Reid of stealing his newspaper during his final illness.

The New York Tribune building was the first home of Pace University. Today, the site of where the building once stood is now the Pace Plaza complex of Pace University's New York City campus. Dr. Choate’s residence and private sanitarium, where Horace Greeley died, is now part of the campus of Pace University in Pleasantville, New York.

Politics

Whig period

In 1838, leading Whig politicians selected Greeley to edit a major national campaign newspaper, the Jeffersonian, which reached 15,000 circulation. Whig leader William Seward found him, "rather unmindful of social usages, yet singularly clear, original, and decided, in his political views and theories." In 1840, Greeley edited a major campaign newspaper, the Log Cabin which reached 90,000 subscribers nationwide, and helped elect William Henry Harrison president on the Whig ticket. In 1841, he merged his papers into the New York Tribune.

Greeley prided himself in taking radical positions on all sorts of social issues; few readers followed his suggestions. Utopia fascinated him; influenced by Albert Brisbane, he promoted Fourierism. His journal had Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as European correspondents in the early 1850s.[4] He promoted all sorts of agrarian reforms, including homestead laws.

Greeley supported liberal policies towards settlers; he memorably advised the ambitious to "Go West, young man." Although this phrase was originally written by John Soule in the Terre Haute Express in 1851, it is most often attributed to Greeley.[5] A champion of the working man, he attacked monopolies of all sorts and rejected land grants to railroads. Industry would make everyone rich, he insisted, as he promoted high tariffs. He supported vegetarianism, opposed liquor, and paid serious attention to any "ism" anyone proposed.

Republican period

When the new Republican Party was founded in 1854, Greeley made the Tribune its unofficial national organ, and fought slavery extension and the slave power on every page. On the eve of the Civil War circulation nationwide approached 300,000.

His editorials and news reports explaining the policies and candidates of the Whig Party were reprinted and discussed throughout the country. Many small newspapers relied heavily on the reporting and editorials of the Tribune. He served as congressman for three months, in 1848 to 1849, but failed in numerous other attempts to win elective office.

He made the Tribune the leading newspaper opposing "Slave Power." That is, it opposed what he considered the conspiracy by slave owners to seize control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. In the secession crisis of 1861 he took a hard line against the Confederacy. Theoretically, he agreed, the South could declare independence; but in reality he said there was "a violent, unscrupulous, desperate minority, who have conspired to clutch power." Thus, secession was an illegitimate conspiracy that had to be crushed by federal power. He took a Radical Republican position during the war, in opposition to Lincoln’s moderation. His famous editorial demanded a more aggressive attack on the Confederacy and faster emancipation of the slaves. A month later he hailed Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

After 1860, he increasingly lost control of the Tribune’s operations, and wrote fewer editorials. In 1864, he expressed defeatism regarding Lincoln’s chances of reelection, an attitude that was echoed across the country when his editorials were reprinted. Oddly he also pursued a peace policy in 1863-64 that involved discussions with Copperheads, and opened the possibility of a compromise with the Confederacy. Lincoln was aghast, but outsmarted Greeley by appointing him to a peace commission he knew the Confederates would repudiate.

Liberal Republican period

During Reconstruction, Greeley took an erratic course, mostly favoring the Radicals and opposing president Andrew Johnson. His personal guarantee of bail for Jefferson Davis in 1867 stunned many of his long-time readers, half of whom canceled their subscriptions. After supporting Ulysses Grant in the 1868 election, Greeley broke with Grant and joined the Liberal Republican party in 1872. To everyone’s astonishment, they nominated Greeley as their presidential candidate. Even more surprisingly, he won the support of many Democrats, whose party he had excoriated for decades.

As a candidate, Greeley argued that Reconstruction was a success, the war was over, the Confederacy destroyed, and slavery was dead. It was time to pull federal troops out of the South and let the people there run their own affairs. A weak campaigner, he was mercilessly ridiculed as a fool, an extremist, a turncoat, and a crazy man who could not be trusted by the Republicans. The most vicious attacks came in cartoons by Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly. Greeley ultimately won 43 percent of the vote. However, he died before the electoral college met.

This crushing defeat was not Greeley's only misfortune in 1872. Greeley was among several high-profile investors who were defrauded by Philip Arnold in a famous diamond and gemstone hoax.[6] Meanwhile, as Greeley had been pursuing his political career, Whitelaw Reid, owner of the New York Herald, had gained control of the Tribune.

Legacy

Greeley represented the potential influence that journalists have over opinion in the country, as he exercised an activist style of reporting and editorializing. This contrasts with the objective style of reporting ostensibly favored in many later major news media. Although Greeley's Tribune is no longer a leading paper, its success under his leadership helped spur competition among other newspapers leading to higher quality information being delivered to audiences across the country.

The Greeley home in Chappaqua, New York now houses the New Castle Historical Society. The local high school there is named after him, and the name of one of the school newspapers pays homage to the nineteenth-century paper owned by Greeley.

Horace Greeley Square is a small park in the Herald Square area of Manhattan, featuring a statute of Greeley. The park is situated adjacent to the site of the former New York Herald building.

Notes

- ↑ Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, Greeley, Horace. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- ↑ U-S-history.com, Horace Greeley. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- ↑ David H. Fenimore, Horace Greeley (1811-1872), Editor of the New York Tribune. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- ↑ Marxists Internet Archive, Articles by Karl Marx in the New York Tribune. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ↑ Bartleby.com, Go West, Young Man. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ↑ Smithsonian.com, The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872. Retrieved December 2, 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cross, Coy F., II. 1995. Go West Young Man! Horace Greeley's Vision for America. University of Mexico Press. ISBN 0826316050

- Downey, Matthew T. 1967. "Horace Greeley and the Politicians: The Liberal Republican Convention in 1872" in The Journal of American History. Vol. 53, No. 4., pp. 727-750.

- Greeley, Horace. 1868. Recollections of a Busy Life.

- Lunde, Erik S. 1978. "The Ambiguity of the National Idea: the Presidential Campaign of 1872" in Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism. 5(1): 1-23.

- Lunde, Erik S. 1981. Horace Greeley. Twayne. ISBN 0805773436

- Nevins, Allan. 1931. "Horace Greeley" in Dictionary of American Biography.

- Parrington, Vernon L. 1927. Main Currents in American Thought.

- Robbins, Roy M. 1933. "Horace Greeley: Land Reform and Unemployment, 1837-1862" in Agricultural History. VII, 18. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- Rourke, Constance Mayfield. 1927. Trumpets of Jubilee: Henry Ward Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lyman Beecher, Horace Greeley, P.T. Barnum.

- Schulze, Suzanne. 1992. Horace Greeley: A Bio-Bibliography. Greenwood. ISBN 0313267367

- Seitz, Don C. 1970 (original 1926). Horace Greeley: Founder of the New York Tribune. AMS Press Inc. ISBN 0404002102

- Van Deusen, Glyndon G. 2000 (original 1953). Horace Greeley, Nineteenth-Century Crusader. Standard biography. Hill & Wang Pub. ISBN 0809000725

- Weisberger, Bernard A. 1977. "Horace Greeley: Reformer as Republican" in Civil War History. 23(1): 5-25.

- Williams, Robert C. 2006. Horace Greeley: Champion of American Freedom. NYU Press. ISBN 0814794025

External links

All links retrieved January 13, 2018.

- Cartoonist Thomas Nast vs. Candidate Horace Greeley The Election of 1872 in Harper's Weekly.

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

- Biography - US History.

- Horace Greeley, An Overland Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859 (1860). Book advocating a Transcontinental Railroad.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.