Gutenberg Bible

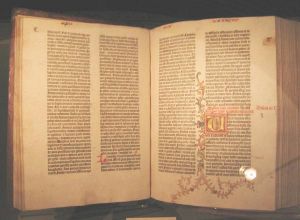

The Gutenberg Bible (also known as the 42-line Bible or the Mazarin Bible) is a printed version of the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible that was printed by Johannes Gutenberg, in Mainz, Germany in the fifteenth century. Although it is not, as often thought, the first book to be printed by Gutenberg's movable type system[1], it is his major work, and has iconic status in the West as the start of the "Gutenberg Revolution" and the "Age of the Printed Book".

The detailed format of the printed bible is a possible imitation of a Mainz illuminated manuscript, the so called Giant Bible of Mainz (Biblia latina), whose 1300 pages were written between 1452 and 1453.

The 42-line Bible

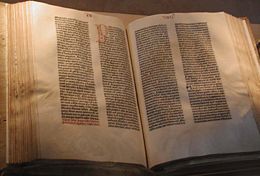

The name "42-line Bible," shortened to B42, refers to the number of lines of print on each page, and is used to differentiate this edition of the Gutenberg Bible from the rarer 36-line Bible, which is also referred to as a Gutenberg Bible. [2] The term "Gutenberg Bible" is most commonly used to refer to the more familiar 42-line edition.

Preparation of the Bible began soon after 1450, and the first finished copies were available in 1454 or 1455, using a printing press and movable type.[3] This Bible is the most famous incunabulum and its production marked the beginning of the mass production of books in the West. It is believed that about 180 copies of the Bible were produced, a number which marks a sharp contrast with the prior technology for European societies which, from time immemorial, had to produce copies of written works laboriously by hand. Gutenberg produced these Bibles (which were printed, then rubricated and illuminated by hand, the work of specialized craftsmen) over a period of a year, the time it would have taken to produce one copy in a Scriptorium. Because of the hand illumination, each copy is unique.

Physical appearance

Volumes

Of the 180 copies of the Bible that were produced, 45 were printed on vellum and 135 on paper. A complete copy comprises 1282 pages, and was bound in two volumes (one known copy is bound in three volumes). At this moment 48 copies are known to exist, not all complete. The locations of these copies are listed below.

Pages

The paper size is 'double folio', with two pages printed on each side (making a total of four pages per single paper). After printing the paper is folded once to the size of a single page . Five of these folded papers (carrying 20 printed pages) were combined to a single physical section, called quinternion, that could then be bound into a book. It is possible that the some sections were printed in a larger number, especially those printed later in the publishing process, and sold unbound. Pagenumbering was not used in the Gutenberg-bible. This whole technique of course was not new, since it was used already to make white-paper books to be written afterwards. New was the necessity to determine beforehand the right place and orientation of each page on the five papers, so as to end up in the right reading sequence. Also, getting the location of the printed area right on the page is a printing technique not in writing. The folio size, 307 x 445 mm, has the ratio of 1.45. The printed area had the same ratio, and was shifted out of the middle to leave a 2:1 white margin, both horizontally and vertically. The scolar Man [4] writes that the ratio is chosen because of being close to the golden ratio of 1.61. To reach this ratio more closely the vertical size should be 338 mm, but there is no reason why Guthenberg would leave this non-trivial difference of 8 mm go by in such a detailed work in other aspects.

Printed area

Although this bible is famously named B42 because having the 42-lines to the page, not all pages have 42 lines by design. Pages 1 to 9 and pages 256 to 265, probably the first printed, count 40 lines. Page 10 has 41, and from there the 42 lines appear. The actual printed area does not change regardless of whether it has 40, 41 or 42 lines, only the interline spacing changes.

Types

B42 is printed in the blackletter type styles that would become known as Textualis (Textura) and Schwabacher. The name texture refers to the texture of the printed page: straight vertical strokes combined with horizontal lines, giving the impression of a woven structure. Gutenberg already used the technique of right-justifying by using bits of extra white space between word, creating a vertical, not indented righthand side of the column. On top of this, he consequently let punctuation marks go beyond that vertical line, thereby using the massive black characters to make this justifying stronger to the eye.

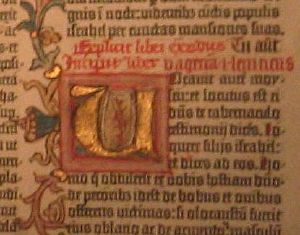

Illustrations

In some copies of the Bible, the headings on a few of the sheets at the top are printed in red; the initial pages were re-composed, and the later copies for those pages are in black only, with the red headers lettered by hand. On all later pages the red headings are added by hand, and a printed list of the text to be added to each page survives. This presumably represents a failed experiment. [5] All the main capitals, called rubrication, were handwritten and illustrated on the places that were intentionally left white. The spacious margin allowed handmade illustrations.

The printing process: 'Das Werk der Bücher'

The idea of using reproducible and reusable types was in itself a valuable invention, and Gutenberg was the first European to do so. But the true achievement of Gutenberg is that he proved that the whole process of printing actually produced books. The process comprised multiple problems to be solved, each problem being a possible showstopper in itself. In a legal paper, written after the production, Gutenberg refers to the printing as 'Das Werk der Bücher' (The work of the books).

Paper and vellum

A single complete copy has 1272 pages. Four pages per folio-sheet requires 318 sheets per copy. The 35 copies on hemp required 11130 sheets. 155 copies on paper required 49290 sheets of paper. The watermarks show that the paper was produced in Italy.

Font

The first part of the Gutenberg idea was using a single, hand-carved character to create identical copies of itself. Cutting a single letter could take a craftsman a day of work, so a less labor intensive method of reproduction was needed. Copies were produced by stamping the original into a iron plate, called a matrix. A rectangular tube was then connected to the matrix, creating a container in which molten lead could be poured. Once cooled, the solid lead form was released from the tube. The end result was a rectangular block of lead with the form of the desired character protruding from the end. This piece of type could be put in a line, facing up, with other pieces of type. These lines were arranged to form blocks of text, which could be inked and pressed against paper, transferring the desired text to the paper.

Each unique character requires a master piece of type in order to be replicated. Given that each letter has uppercase and lowercase forms, and the number of various punctuation marks and ligatures (e.g. the sequence 'fi' combined in one character, commonly used in writing) the Gutenberg Bible needed a set of 290 master characters.

Types

A single page has about 500 words, and 2600 characters. A sheet of paper requires two pages to be available simultaneously, that's 5200 characters at any one moment on the press table. The scholar John Man describes[6] a calculation of the number of types required. Preparation takes another two pages (5200 characters) to be set. Then decomposition after printing two previous pages requires another 5200 characters. At any moment, six pages containing 15600 characters altogether were existing at any one moment. Since it would take a craftsman a whole day to hand-cut type for one character, such a large number was probably produced through the mass-production of copies of one master-type.

The 36-line Bible

In the past, there was no consensus on the order of editions. Some specialists like Richard Schwab and Thomas Cahill argued that the rarer 36-line Bible is actually the older, cruder version, and that the 42-line Bible was a second, more numerous and perfected edition of Gutenberg's Bible.[7]. Others, like Richard W. Clement, argued that the 36-line Bible was printed in 1458, 3 years after the 42-line Bible, but with an older typefont.[8] The dispute, however, has been settled; the line endings on the pages of the 36 line Bible make it evident that the text is based on a copy of the 42-line Bible. (Kapr, "Johannes Gutenberg." Scolar, 1996)

Existing copies of the Gutenberg Bible

As of 2007, there are 48 Gutenberg 42-line Bibles known to exist, of which 21 are perfect. This includes eleven complete copies (four of which are perfect) on vellum, and one copy of the New Testament only on vellum. In addition, there are a substantial number of fragments, some as small as individual leaves—at least one copy is known to have been partially broken up to be sold in parts.

The country with the most copies is Germany, which has twelve, whilst the United States has eleven and the United Kingdom eight. Mainz, Russia and the Vatican City contain two copies, Paris and London have three copies, and New York has four copies. Three identified copies have been lost — two disappeared from Leipzig after the end of the Second World War, and one is known to have been destroyed along with the library of the Catholic University of Leuven in 1914. However, the former two were rediscovered in recent years, both in Moscow, where they had been taken.

A full listing of known copies and brief details on their condition can be found in the British Library's Incunabula Short Title Catalogue, ISTC number ib00526000. The 36-line bible is catalogued as ISTC number ib00527000. Copy numbers are as found in the ISTC, taken from a 1985 survey of existing copies by Ilona Hubay; the two copies in Russia were not known to exist in 1985, and so were not catalogued. A more detailed census, with some notes on provenance, is online at Clausen Books. "Perfect" or "imperfect" refers to completeness—whether a volume still contains all its leaves.

| Country | Holding institution | Hubay-nr | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria (1) | Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna | 27 | Perfect, paper |

| Belgium (1) | Bibliothèque universitaire, Mons | 1 | Imperfect, paper |

| Denmark (1) | Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen | 12 | Vol. II, imperfect, paper |

| France (4) | Bibliothèque nationale, Paris | 15 | Perfect, vellum |

| 17 | Imperfect, paper. Contains note by binder dating it to August 1456 | ||

| Bibliothèque Mazarine, Paris | 16 | Perfect, paper | |

| Bibliothèque Municipale, Saint-Omer | 18 | Imperfect, paper | |

| Germany (12) | Gutenberg Museum, Mainz | 8 | One copy is vol. I, imperfect, paper; the other both vols., imperfect, paper. It is unclear which is which. |

| 9 | |||

| Landesbibliothek, Fulda | 4 | Vol. I, imperfect, vellum | |

| Universitätsbibliothek, Leipzig | 14 | Imperfect, vellum | |

| Niedersächsische Staats-und Universitätsbibliothek, Göttingen | 2 | Perfect, vellum | |

| Staatsbibliothek, Berlin | 3 | Imperfect, vellum | |

| Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich | 5 | Perfect, paper | |

| Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek, Frankfurt-am-Main | 6 | Perfect, paper | |

| Hofbibliothek, Aschaffenburg | 7 | Imperfect, paper | |

| Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart | 10 | Imperfect, paper. Purchased in April 1978 for 2.2 million US dollars. | |

| Stadtbibliothek, Trier | 11 | Vol.I?, imperfect, paper. Possibly sister volume to Hubay 46, in Indiana | |

| Landesbibliothek, Kassel | 12 | Vol. I, imperfect, paper | |

| Japan (1) | Keio University Library, Tokyo | 45 | Vol. I, imperfect, paper. Purchased in October 1987 for either 4.9 or 5.4 million US dollars (sources disagree) |

| Poland (1) | Biblioteka Seminarium Duchownego, Pelpin | 28 | Imperfect, paper |

| Portugal (1) | Portuguese National Library, Lisbon | 29 | Perfect, paper |

| Russia (2) | Russian National Library | - | Imperfect, vellum |

| Lomonosov University Library, Moscow | - | Perfect, paper | |

| Spain (2) | Biblioteca Universitaria y Provincial, Seville | 32 | Vol. II, imperfect, paper |

| Biblioteca Pública Provincial, Burgos | 31 | Perfect, paper | |

| Switzerland (1) | Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, Cologny | 30 | Imperfect, paper |

| United Kingdom (8) | British Library, London | ? | Perfect, vellum |

| ? | Perfect, paper | ||

| National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh | 26 | Perfect, paper | |

| Lambeth Palace Library, London | 20 | Vol. II (New Testament only), imperfect, vellum | |

| Eton College Library, Eton | 23 | Perfect, paper | |

| John Rylands Library, Manchester | 25 | Perfect, paper | |

| Bodleian Library, Oxford | 24 | Perfect, paper | |

| University Library, Cambridge | 22 | Perfect, paper | |

| United States (11) | The Morgan Library & Museum, New York | 37 | Imperfect, vellum |

| 38 | Perfect, paper | ||

| 44 | Imperfect, paper | ||

| Library of Congress, Washington DC | 35 | Perfect, vellum | |

| New York Public Library | 42 | Imperfect, paper | |

| Widener Library, Harvard University | 40 | Perfect, paper | |

| Beinecke Library, Yale University | 41 | Perfect, paper | |

| Scheide Library, Princeton University | 43 | Imperfect, paper | |

| Lilly Library, Indiana University | 46 | Imperfect, paper. Possibly sister volume to Hubay 11, in Trier | |

| Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino | 36 | Imperfect, vellum | |

| University of Texas at Austin | 39 | Perfect, paper. Purchased in 1974 for 2.4 million US dollars. | |

| Vatican City (2) | Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana | 33 | Imperfect, vellum |

| 34 | Vol I, imperfect, paper |

Prices and dealers

- In the 1920s a New York book dealer, Gabriel Wells, bought a damaged paper copy, dismantled the book and sold sections and individual leaves to book collectors and libraries. The leaves were sold in a portfolio case with an essay written by A. Edward Newton. [9] (Also referred to as a "Noble Fragment") These leaves now sell for $20,000–$100,000 depending upon condition and the desirability of the page.

- On 22 October 1987 a Japanese buyer, Eiichi Kobayashi, a director at the Maruzen Company, purchased the Old Testament portion (Hubay 45) for $5.4 million at a Christie's Auction.[10] The last sale of a complete Gutenberg Bible took place nine years before, again at Christie's, for $2.2 million.

Media References

- In the movie The Day After Tomorrow, people burned books to try to stay warm in the New York City Public Library. One character was holding the library's copy of the Gutenberg Bible to protect it from being burned.

- In the game Freedom Force vs The 3rd Reich a villain named Fortissimo tried to burn the Gutenberg Bible but was stopped by the Freedom Force.

- In the movie Futurama: Bender's Big Score, Bender returns to the past and steals the Gutenberg Bible which contains the Colonel's secret recipe: "Chicken, grease, salt".

- In the BBC TV series Doctor Who episode "The City of Death" Count Scarlioni orders the sale of a Gutenberg Bible to fund his experiments with time.

See also

- For other works printed by Gutenberg or from the workshop he founded, See: Johannes Gutenberg.

- Printing press

Notes

- ↑ Man, John [2002]. "6", Gutenberg; How one man remade the world with words. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 312. ISBN 0471218235. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Plantin-Moretus museum

- ↑ University of Texas -The Gutenberg Bible

- ↑ 1996, Johann Gutenberg: The Man and is Invention (3rd ed.), [Solar Press, ISBN 1-85928-114-1

- ↑ Karp, Albert (1996), Johann Gutenberg: The Man and is Invention (3rd ed.), [Solar Press, ISBN 1-85928-114-1

- ↑ Man, John [2002]. Gutenberg; How one man remade the world with words. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 312. ISBN 0471218235. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Time Magazine, March 10, 1986

- ↑ Orb Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ Kenyon College Library http://lbis.kenyon.edu/sca/exhibits/incunabula/z241b58.phtml

- ↑ New York Times

External links

- Treasures in Full: Gutenberg Bible Complete digitized texts of the two Gutenberg bibles in the British Library

- The University of Texas Ransom Center's Gutenberg Bible website including detailed images

- Online digital edition

- Gutenberg site made by the city of Mainz

A complete link list of digitized copies can be found in the German wikipedia.[1]

ar:بيبل غوتنبرغ cs:Gutenbergova bible da:Gutenbergbibelen de:Gutenberg-Bibel es:Biblia de Gutenberg eo:Biblio de Gutenberg fr:Bible de Gutenberg ko:구텐베르크 성서 id:Kitab Gutenberg he:תנ"ך גוטנברג ka:გუტენბერგის ბიბლია mr:गटेनबर्ग बायबल nl:Gutenbergbijbel ja:グーテンベルク聖書 pl:Biblia Gutenberga pt:Bíblia de Gutenberg simple:Gutenberg Bible fi:Gutenbergin Raamattu sv:Gutenbergs Bibel zh:古腾堡圣经

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.