Difference between revisions of "Giant star" - New World Encyclopedia

(→External links: Checked link and added Retrieved date.) |

(Checked spelling and applied Ready tag.) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Ready}} | ||

{{star nav}} | {{star nav}} | ||

| − | A '''giant star''' is a [[star]] with substantially larger [[radius]] and [[luminosity]] than a [[main sequence]] star of the same [[effective temperature|surface temperature]].<ref name="oxford">Moore, Patrick. 2002. "Giant star", in ''Astronomy Encyclopedia''. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195218337.</ref> Typically, giant stars have radii between 10 and 100 [[solar radii]] and luminosities between 10 and 1,000 times that of the [[Sun]]. Stars still more luminous than giants are referred to as [[supergiants]] and [[hypergiants]].<ref name="darlingsg">Darling, David. [http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/S/supergiant.html Supergiant]. The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Retrieved December 14, 2008.</ref><ref>Darling, David. [http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/H/hypergiant.html Hypergiant]. The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Retrieved December 14, 2008.</ref> | + | A '''giant star''' is a [[star]] with substantially larger [[radius]] and [[luminosity]] than a [[main sequence]] star of the same [[effective temperature|surface temperature]].<ref name="oxford">Moore, Patrick. 2002. "Giant star", in ''Astronomy Encyclopedia''. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195218337.</ref> Typically, giant stars have radii between 10 and 100 [[solar radii]] and luminosities between 10 and 1,000 times that of the [[Sun]]. Stars still more luminous than giants are referred to as [[supergiants]] and [[hypergiants]].<ref name="darlingsg">Darling, David. [http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/S/supergiant.html Supergiant]. The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Retrieved December 14, 2008.</ref><ref>Darling, David. [http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/H/hypergiant.html Hypergiant]. The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Retrieved December 14, 2008.</ref> A hot, luminous main sequence star may also be referred to as a giant.<ref name="cambridge">Mitton, Jacqueline. 2001. "Giant star", in ''Cambridge Dictionary of Astronomy''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521800455.</ref> Apart from this, because of their large radii and luminosities, giant stars lie above the main sequence (luminosity class '''V''' in the [[Spectral classification#Yerkes spectral classification|Yerkes spectral classification]]) on the [[Hertzsprung-Russell diagram]] and correspond to luminosity classes '''II''' or '''III'''.<ref name="fof">Daintith, John, and William Gould eds. 2006. "Giant", in ''The Facts on File Dictionary of Astronomy'', 5th ed. New York, NY: Facts On File, Inc. ISBN 0816059985.</ref> |

==Formation== | ==Formation== | ||

| − | A star becomes a giant star after all the [[hydrogen]] available for [[nuclear fusion|fusion]] at its core has been depleted and, as a result, it has left the [[main sequence]].<ref name="fof" /> | + | A star becomes a giant star after all the [[hydrogen]] available for [[nuclear fusion|fusion]] at its core has been depleted and, as a result, it has left the [[main sequence]].<ref name="fof" /> A star whose initial mass is less than approximately 0.4 [[solar mass]]es will not become a giant star. This is because such stars have their interior thoroughly mixed by [[convection]] and therefore continue fusing hydrogen until it is exhausted throughout the star, at which point they become [[white dwarf]]s, composed chiefly of [[helium]]. This exhaustion, however, is predicted to take significantly longer than the lifetime of the [[Universe]] up to now.<ref name="rln">Richmond, Michael. [http://spiff.rit.edu/classes/phys230/lectures/planneb/planneb.html Late stages of evolution for low-mass stars]lecture notes, Physics 230. [[Rochester Institute of Technology]]. Retrieved December 14, 2008.</ref> |

[[Image:Solar-type Red Giant structure.jpg|right|thumb|400px|Internal structure of a Sun-like star and a red giant. ''[[European Southern Observatory|ESO]] image.'']] | [[Image:Solar-type Red Giant structure.jpg|right|thumb|400px|Internal structure of a Sun-like star and a red giant. ''[[European Southern Observatory|ESO]] image.'']] | ||

| − | If a star is more massive than this lower limit, then when it consumes all of the [[hydrogen]] in its core | + | If a star is more massive than this lower limit, then when it consumes all of the [[hydrogen]] in its core available for [[nuclear fusion|fusion]], the core will begin to contract. Hydrogen now fuses to [[helium]] in a shell around the helium-rich core, and the portion of the star outside the shell expands and cools. During this portion of its [[stellar evolution|evolution]], labeled the [[subgiant]] branch on the [[Hertzsprung-Russell diagram]], the [[luminosity]] of the star remains approximately constant and its [[effective temperature|surface temperature]] decreases. Eventually the star will start to ascend the [[red giant branch]] on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. At this point the surface temperature of the star, now typically a [[red giant]], will remain approximately constant as its luminosity and radius increase drastically. The core will continue to contract, raising its temperature.<ref name="evo">Salaris, Maurizio, and Santi Cassisi. 2005. ''Evolution of Stars and Stellar Populations''. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 047009219X.</ref><sup>, § 5.9.</sup> |

| − | If the star's mass, when on the main sequence, was below approximately 0.5 [[solar mass]]es, it is thought that it will never attain the central temperatures necessary to fuse [[helium]].<ref>Kepler, S.O., and P.A. Bradley. 1995. [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995BaltA...4..166K Structure and Evolution of White Dwarfs]. ''Baltic Astronomy''. 4:166–220. Retrieved December 14, 2008.</ref><sup>, p. 169.</sup> | + | If the star's mass, when on the main sequence, was below approximately 0.5 [[solar mass]]es, it is thought that it will never attain the central temperatures necessary to fuse [[helium]].<ref>Kepler, S.O., and P.A. Bradley. 1995. [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995BaltA...4..166K Structure and Evolution of White Dwarfs]. ''Baltic Astronomy''. 4:166–220. Retrieved December 14, 2008.</ref><sup>, p. 169.</sup> It will therefore remain a hydrogen-fusing red giant until it eventually becomes a helium white dwarf.<ref name="evo" /><sup>, § 4.1, 6.1.</sup> Otherwise, when the core temperature reaches approximately 10<sup>8</sup> K, helium will begin to fuse to [[carbon]] and [[oxygen]] in the core by the [[triple-alpha process]].<ref name="evo" /><sup>,§ 5.9, chapter 6.</sup> The energy generated by helium fusion causes the core to expand. This causes the pressure in the surrounding hydrogen-burning shell to decrease, which reduces its energy-generation rate. The luminosity of the star decreases, its outer envelope contracts again, and the star leaves the [[red giant branch]].<ref name="psu">Ciardullo, Robin. [http://www.astro.psu.edu/users/rbc/a534/lec23.pdf Giants and Post-Giants]. class notes, Astronomy 534. [[Penn State University]]. Retrieved December 14, 2008.</ref> Its subsequent evolution will depend on its mass. If not very massive, it may be found in the [[horizontal branch]] on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, or its position in the diagram may move in loops.<ref name="evo" /><sup>, chapter 6.</sup> If the star is not heavier than approximately 8 solar masses, it will eventually exhaust the helium at its core and begin to fuse helium in a shell around the core. It will then increase in luminosity again as, now an [[AGB star]], it ascends the [[asymptotic giant branch]] of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. After the star sheds most of its mass, its core will remain as a carbon-oxygen [[white dwarf]].<ref name="evo" /><sup>, § 7.1–7.4.</sup> |

| − | For main-sequence stars with masses great enough to eventually fuse [[carbon]] (approximately 8 [[solar mass]]es)<ref name="evo" /><sup>, p. 189</sup>, this picture must be modified in many ways. These stars do not increase greatly in luminosity after leaving the main sequence, but they will become redder. They may become [[red supergiant]]s, or [[Stellar mass loss|mass loss]] may cause them to become [[blue supergiant]]s.<ref>Hartquist, T.W., J.E. Dyson, and D. P. Ruffle. 2004. ''Blowing Bubbles in the Cosmos: Astronomical Winds, Jets, and Explosions''. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195130545.</ref><sup>, pp. 33–35; </sup><ref name="darlingsg" /> | + | For main-sequence stars with masses great enough to eventually fuse [[carbon]] (approximately 8 [[solar mass]]es)<ref name="evo" /><sup>, p. 189</sup>, this picture must be modified in many ways. These stars do not increase greatly in luminosity after leaving the main sequence, but they will become redder. They may become [[red supergiant]]s, or [[Stellar mass loss|mass loss]] may cause them to become [[blue supergiant]]s.<ref>Hartquist, T.W., J.E. Dyson, and D. P. Ruffle. 2004. ''Blowing Bubbles in the Cosmos: Astronomical Winds, Jets, and Explosions''. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195130545.</ref><sup>, pp. 33–35; </sup><ref name="darlingsg" /> Eventually, they will become [[white dwarf]]s composed of [[oxygen]] and [[neon]], or will undergo a [[core-collapse supernova]] to form [[neutron star]]s, or [[black hole]]s.<ref name="evo" /><sup>, § 7.4.4–7.8.</sup> |

==Examples== | ==Examples== | ||

Revision as of 06:06, 14 December 2008

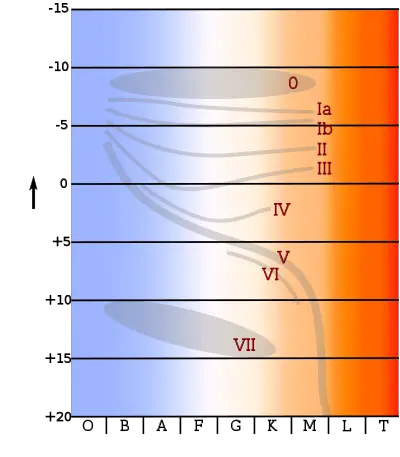

A giant star is a star with substantially larger radius and luminosity than a main sequence star of the same surface temperature.[1] Typically, giant stars have radii between 10 and 100 solar radii and luminosities between 10 and 1,000 times that of the Sun. Stars still more luminous than giants are referred to as supergiants and hypergiants.[2][3] A hot, luminous main sequence star may also be referred to as a giant.[4] Apart from this, because of their large radii and luminosities, giant stars lie above the main sequence (luminosity class V in the Yerkes spectral classification) on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram and correspond to luminosity classes II or III.[5]

Formation

A star becomes a giant star after all the hydrogen available for fusion at its core has been depleted and, as a result, it has left the main sequence.[5] A star whose initial mass is less than approximately 0.4 solar masses will not become a giant star. This is because such stars have their interior thoroughly mixed by convection and therefore continue fusing hydrogen until it is exhausted throughout the star, at which point they become white dwarfs, composed chiefly of helium. This exhaustion, however, is predicted to take significantly longer than the lifetime of the Universe up to now.[6]

If a star is more massive than this lower limit, then when it consumes all of the hydrogen in its core available for fusion, the core will begin to contract. Hydrogen now fuses to helium in a shell around the helium-rich core, and the portion of the star outside the shell expands and cools. During this portion of its evolution, labeled the subgiant branch on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, the luminosity of the star remains approximately constant and its surface temperature decreases. Eventually the star will start to ascend the red giant branch on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. At this point the surface temperature of the star, now typically a red giant, will remain approximately constant as its luminosity and radius increase drastically. The core will continue to contract, raising its temperature.[7], § 5.9.

If the star's mass, when on the main sequence, was below approximately 0.5 solar masses, it is thought that it will never attain the central temperatures necessary to fuse helium.[8], p. 169. It will therefore remain a hydrogen-fusing red giant until it eventually becomes a helium white dwarf.[7], § 4.1, 6.1. Otherwise, when the core temperature reaches approximately 108 K, helium will begin to fuse to carbon and oxygen in the core by the triple-alpha process.[7],§ 5.9, chapter 6. The energy generated by helium fusion causes the core to expand. This causes the pressure in the surrounding hydrogen-burning shell to decrease, which reduces its energy-generation rate. The luminosity of the star decreases, its outer envelope contracts again, and the star leaves the red giant branch.[9] Its subsequent evolution will depend on its mass. If not very massive, it may be found in the horizontal branch on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, or its position in the diagram may move in loops.[7], chapter 6. If the star is not heavier than approximately 8 solar masses, it will eventually exhaust the helium at its core and begin to fuse helium in a shell around the core. It will then increase in luminosity again as, now an AGB star, it ascends the asymptotic giant branch of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. After the star sheds most of its mass, its core will remain as a carbon-oxygen white dwarf.[7], § 7.1–7.4.

For main-sequence stars with masses great enough to eventually fuse carbon (approximately 8 solar masses)[7], p. 189, this picture must be modified in many ways. These stars do not increase greatly in luminosity after leaving the main sequence, but they will become redder. They may become red supergiants, or mass loss may cause them to become blue supergiants.[10], pp. 33–35; [2] Eventually, they will become white dwarfs composed of oxygen and neon, or will undergo a core-collapse supernova to form neutron stars, or black holes.[7], § 7.4.4–7.8.

Examples

Well-known giant stars of various colors include

- Alcyone (η Tauri), a blue-white (B-type) giant,[11] the brightest star in the Pleiades.[12]

- Thuban (α Draconis), a white (A-type) giant.[13]

- σ Octantis, a yellow-white (F-type) giant.[14]

- α Aurigae Aa, a yellow (G-type) giant, one of the stars making up Capella.[15]

- Pollux (β Geminorum), an orange (K-type) giant.[16]

- Mira (ο Ceti), a red (M-type) giant.[17]

See also

- Blue giant

- Hypergiant

- Red giant

- Supergiant

Notes

- ↑ Moore, Patrick. 2002. "Giant star", in Astronomy Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195218337.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Darling, David. Supergiant. The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Darling, David. Hypergiant. The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Mitton, Jacqueline. 2001. "Giant star", in Cambridge Dictionary of Astronomy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521800455.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Daintith, John, and William Gould eds. 2006. "Giant", in The Facts on File Dictionary of Astronomy, 5th ed. New York, NY: Facts On File, Inc. ISBN 0816059985.

- ↑ Richmond, Michael. Late stages of evolution for low-mass starslecture notes, Physics 230. Rochester Institute of Technology. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Salaris, Maurizio, and Santi Cassisi. 2005. Evolution of Stars and Stellar Populations. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 047009219X.

- ↑ Kepler, S.O., and P.A. Bradley. 1995. Structure and Evolution of White Dwarfs. Baltic Astronomy. 4:166–220. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Ciardullo, Robin. Giants and Post-Giants. class notes, Astronomy 534. Penn State University. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Hartquist, T.W., J.E. Dyson, and D. P. Ruffle. 2004. Blowing Bubbles in the Cosmos: Astronomical Winds, Jets, and Explosions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195130545.

- ↑ Alcyone. SIMBAD. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Kaler, Jim. Alcyone. STARS. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Thuban. SIMBAD. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Sigma Octantis. SIMBAD. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ α Aurigae Aa. SIMBAD. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Pollux. SIMBAD. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ↑ Mira. SIMBAD. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Daintith, John, and William Gould eds. 2006. The Facts on File Dictionary of Astronomy, 5th ed. New York, NY: Facts On File, Inc. ISBN 0816059985.

- Hartquist, T.W., J.E. Dyson, and D. P. Ruffle. 2004. Blowing Bubbles in the Cosmos: Astronomical Winds, Jets, and Explosions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195130545.

- Mitton, Jacqueline. 2001. Cambridge Dictionary of Astronomy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521800455.

- Moore, Patrick ed. 2002. Astronomy Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195218337.

- Salaris, Maurizio, and Santi Cassisi. 2005. Evolution of Stars and Stellar Populations. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 047009219X.

External links

- Interactive giant star comparison. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.