Difference between revisions of "Freyja" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

:''For other meanings of Freya, see [[Freya (disambiguation)]].'' | :''For other meanings of Freya, see [[Freya (disambiguation)]].'' | ||

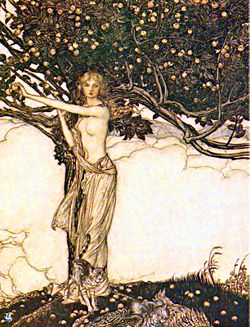

| − | [[Image:Freya.jpg|thumb|250px|Freyja, in an illustration to [[Richard Wagner|Wagner]]'s operas by | + | [[Image:Freya.jpg|thumb|250px|Freyja, in an illustration to [[Richard Wagner|Wagner]]'s operas by Arthur Rackham.]] |

| − | '''Freyja''' (sometimes anglicized as '''Freya''' or '''Freja'''), sister of [[Freyr]] and daughter of [[ | + | '''Freyja''' (sometimes anglicized as '''Freya''' or '''Freja'''), sister of [[Freyr]] and daughter of [[Njord]] (''{{unicode|Njǫrðr}}''), is most typically viewed as a Norse [[fertility goddess]]. This connection to the feminine begins at the etymological level, as her name itself means "lady" in Old Norse (cf. ''fru'' or ''Frau'' in Scandinavian and German). |

| − | + | While there are some sources suggesting that she was called on to bring fruitfulness to fields or wombs, Freyja was more explicitly connected to the ideas of love, beauty, sex, and interpersonal attraction. However, she was also a goddess of war, death, magic, prophecies and wealth. Freya is cited as receiving half of the dead lost in battle in her hall, whereas [[Odin]] would receive the other half. Further, according to Snorri's ''Ynglinga saga'', Freyja was a skilled practitioner of the ''[[Seid|seiðr]]'' form of magic and introduced it amongst the Aesir. | |

| − | + | Given her variegated spheres of influence, it is not surprising that Freyja was one of the most popular goddesses in the [[Norse Mythology|Norse pantheon]]. | |

==Freyja in a Norse Context== | ==Freyja in a Norse Context== | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the [[Aesir]], the [[Vanir]], and the [[Jotun]]. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war, which the Aesir had finally won. In fact, the most significant divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.<ref>More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.</ref> The ''Jotun'', on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir. | Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the [[Aesir]], the [[Vanir]], and the [[Jotun]]. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war, which the Aesir had finally won. In fact, the most significant divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.<ref>More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.</ref> The ''Jotun'', on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir. | ||

| − | + | The primary role of Freyja, who was one of the most exalted of the Vanir, was as a goddess of love and sexual desire. | |

==Attributes== | ==Attributes== | ||

Revision as of 17:56, 15 March 2007

- For other meanings of Freya, see Freya (disambiguation).

Freyja (sometimes anglicized as Freya or Freja), sister of Freyr and daughter of Njord (Njǫrðr), is most typically viewed as a Norse fertility goddess. This connection to the feminine begins at the etymological level, as her name itself means "lady" in Old Norse (cf. fru or Frau in Scandinavian and German).

While there are some sources suggesting that she was called on to bring fruitfulness to fields or wombs, Freyja was more explicitly connected to the ideas of love, beauty, sex, and interpersonal attraction. However, she was also a goddess of war, death, magic, prophecies and wealth. Freya is cited as receiving half of the dead lost in battle in her hall, whereas Odin would receive the other half. Further, according to Snorri's Ynglinga saga, Freyja was a skilled practitioner of the seiðr form of magic and introduced it amongst the Aesir.

Given her variegated spheres of influence, it is not surprising that Freyja was one of the most popular goddesses in the Norse pantheon.

Freyja in a Norse Context

As a Norse deity, Freyja belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E..[1] The tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to exemplify a unified cultural focus on physical prowess and military might.

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war, which the Aesir had finally won. In fact, the most significant divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.[2] The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

The primary role of Freyja, who was one of the most exalted of the Vanir, was as a goddess of love and sexual desire.

Attributes

Mythic Accounts

Prose Edda

In Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda, Freyja is introduced as follows.

|

|

Snorri also mentions that Freyja had a husband named Odr. He often went away on long journeys, and for this reason Freyja cried tears of red gold. The Lay of Hyndla also names a protégé of Freyja, Óttar.

In two stories a giant wants to marry Freyja; the owner of Svaðilfari as related in Gylfaginning and Þrymr as related in Þrymskviða. Both were ultimately deceived and killed by the gods.

Possessions

Surviving tales regarding Freyja often associate Freyja with numerous enchanted possessions.

Cloak

Freya owned a cloak of robin feathers, which gave her the ability to change into any bird. She lends this garment to Loki in Þrymskviða.

Hildisvini

Freyja rides a boar called Hildisvín the Battle-Swine. In the poem Hyndluljóð, we are told that in order to conceal Ottar, Freyja transformed him into the guise of a boar. The boar has special associations within Norse Mythology, both relative to the notion of fertility and also as a protective talisman in war.

Other sources show that Freyja rode a chariot drawn by a pair of cats.

Jewelry

In the Eddas, Freyja is often portrayed as being thought to be the most desirable of all goddesses. When she desired to acquire the famous necklace Brisingamen (Brísingamen) from four dwarves, (Dvalin, Alfrik, Berling, and Grer), they desired a night each with her, a demand which she eventually acceded to.

Later on, Odin made Loki steal the necklace for him, and demanded the same price of Freyja as the dwarves had, though he eventually relented. Freyja loved jewelery so much that she named her daughter "Hnoss", meaning "jewel".

Association with war

The earliest example of Freyja's association with war comes from Sörla þáttr alias The Saga of Hedin and Högni written c. 1400. It is not-so-vague attempt to immortalize the Christian King Olaf Tryggvason in mythic terms. His ascension to rulership and subsequent conversion to Christianity of all Norway became the culmination of prophecy and even the will and direct action of Heathen Gods. Odin himself, in this tale, declared it to be so. Also here, Freyja steps completely out of character and urges a man to commit murder and kidnapping to start a war. She does not step into battle herself, nor does she ever touch a weapon.

This clearly non-original story has had surprising influence over the centuries. It is quite clear that this deliberate work is the origin for most 'Freyja-as-War-Goddess' conceptualizations known today. Without Olaf Tryggvason's conversion at the heart of the story - there is no story. Snorri Sturlusson even writes about the same war and Olaf's victory without making any reference to Freyja or the old gods at all - and his version predates Sörla þáttr.

Receiver of half the slain

Snorri writes in Gylfaginning (24) that "wherever she rides to battle, she gets half the slain" (Faulkes translation); he does not say whether or not Freyja actively participates in the battle in any way. Though Freyja receives some of those warriors slain on the battlefield, there is no record of how that occurs. Does Freyja pick them herself? Or do Odin or the Valkyries decide? There are no answers to these questions.

It is said in Grímnismál:

- The ninth hall is Folkvang, where bright Freyja

- Decides where the warriors shall sit:

- Some of the fallen belong to her,

- And some belong to Odin.

In Egil's saga, Thorgerda (Þorgerðr), threatens to commit suicide in the wake of her brother's death, saying: "I shall not eat until I sup with Freyja". This should be taken to mean that she expected to pass to Freyja's hall upon her death. Any greater associations with Freyja and death are not supported.

19th century accounts

Since rural Scandinavians remained dependent on the forces of nature, it is hardly surprising that fertility gods remained important, and still in rural 19th century Sweden, Freyja retained elements of her role as a fertility goddess.[3] In the province of Småland, there is an account of how she was connected with sheet lightning in this respect[3]:

|

Jag minns en söndag på 1880-talet, det var några gubbar ute och gick bland åkrarna och tittade på rågen som snart var mogen. Då sa Måns i Karryd: "Nu ä Fröa ute å sir ätter om råjen är mogen." [...] När jag som liten pojke satt hos den gamla Stolta-Katrina, var jag som alla dåtida barn mycket rädd för åskan. När kornblixtarna syntes om kvällarna, sade Katrina: "Du sa inte va rädd barn lella, dä ä bara Fröa som ä ute å slår ell med stål å flenta för å si etter om kornet ä moet. Ho ä snäll ve folk å gör dä bare för å hjälpa, ho gör inte som Tor, han slår ihjäl både folk å fä, när han lynna [...] Jag har sedan hört flera gamla tala om samma sak, på ungefär samma sätt.[4] |

I remember a Sunday in the 1880s, when some men were walking in the fields looking at the rye which was about to ripen. Then Måns in Karryd said: "Now Freyja is out watching if the rye is ripe" [...] When as a boy I was visiting the old Proud-Katrina, I was afraid of lightning like all boys in those days. When the sheet lightning flared in the nights, Katrina said: "Don't be afraid little child, it is only Freyja who is out making fire with steel and flintstone to see if the rye is ripe. She is kind to people and she is only doing it to be of service, she is not like Thor, he slays both people and livestock, when he is in the mood" [...] I later heard several old folks talk of the same thing in the same way.[5] |

In Värend, Freyja could also arrive at Christmas night and she used to shake the apple trees for the sake of a good harvest and consequently people left some apples in the trees for her sake.[3] Moreover, it was dangerous to leave the plough outdoors, because if Freyja sat on it, it would no longer be of any use.[3]

Other names

Forms of "Freyja"

- Freja — common Danish and literary Swedish form. as in Freja Andrews of Westport.

- Freia

- Freya

- Froya

- Friia — second Merseburg Charm

- Frija — variant of Friia

- Frøya, Fröa — common Norwegian, and rural Swedish form.

- Reija — Finnish form

Other forms

According to Snorri Sturluson's Gylfaginning (35), Freyja also bore the following names:

- "Vanadis", which means "Dís of the Vanir".

- Mardöll, whose etymology is uncertain, also appears in kennings for gold;

- Hörn, which may be related to the word hörr meaning "flax", "linen" (Hörn is also listed in the þulur as a giantess name);

- Gefn, which means "the giver", is a suitable name for a fertility goddess;

- Sýr, whose translation is "sow", illustrates the association of the Vanir with pigs (cf. Freyr's boar Gullinbursti).

Some of these names (Hörn, Sýr, Gefn, Mardöll) are also listed in a þula which also supplies:

- Þrungva;

- Skjálf, which is also the name of the wife and murderer of king Agni.

Toponyms (and Other Linguistic Traces) of Freyja

Etymology

The Danish verb "fri" means "to propose". In Dutch, the verb "vrijen" is derived from "Freya" and means "to have sex/make love". The (obsolete) German verb "freien" means "looking for a bride". The derived noun "Freier" (suitor) is still used, though more often in its second meaning "client of a prostitute".

In Avestan, an ancient Indo-European language found in the Gathas, "frya" is used to mean "lover","beloved", and "friend". The Sanskrit word Priya- has approximately the same meaning.

Places

Many farms in Norway have Frøy- as the first element in their names, and the most common are the name Frøyland (13 farms). But whether Frøy- in these names are referring to the goddess Freyja (or the god Freyr) is questionable and uncertain. The first element in the name Frøyjuhof, in Udenes parish, are however most probably the genitive case of the name Freyja. (The last element is hof 'temple', and a church was built on the farm in the Middle Ages, which indicates the spot as an old holy place.) The same name, Frøyjuhof, also occur in the parishes Hole and Stjørdal.

In the parish of Seim, in the county of Hordaland, Norway, lies the farm Ryland (Norse Rýgjarland). The first element is the genitive case of rýgr 'lady' (identical with the meaning of the name Freyja, see above). Since the neighbouring farms have the names Hopland (Norse Hofland 'temple land') and Totland (Norse Þórsland 'Thor's land') it is possible that rýgr (lady) here are referring to a goddess. (And in that case most probably Freyja.) A sideform of the word (rýgja) may occur in the name of the Norwegian municipality Rygge.

There´s Horn in Iceland and Hoorn in Holland, various places in the German lands are called Freiburg (burg meaning something like settlement).

Plants

Several plants were named after Freyja, such as Freyja's tears and Freyja's hair (Polygala vulgaris), but after the introduction of Christianity, they were renamed after the Virgin Mary, suggesting her closest homologue in Christianity[6].

Misc

Friday (Freyja Day) is the fifth day of the week in Germanic language speaking countries.

The Orion constellation was called Frigg's distaff or Freyja's distaff[6].

The chemical element vanadium is named after Freyja via her alternative name Vanadis.

Homologues

Freyja might be considered the counterpart of Venus and Aphrodite, although she has a combination of attributes no known goddess possesses in the mythology of any other ancient Indo-European people and might be regarded as closer to the Mesopotamian Ishtar as being involved in both love and war. It is also sometimes thought that she is the most direct mythological descendant from Nerthus.[citation needed]

Britt-Mari Näsström posits in her "Freyja: Great Goddess of the North" that there is a tenable connection from Freyja to other Goddesses worshipped along the migration path of the Indo-Europeans who consistently appeared with either one or two cats/lions as companions, usually in the war Goddess aspect but occasionally also as a love Goddess. These would include: Durga, Ereshkegal, Sekhmet, Menhit, Bast, Anat, Asherah, Nana, Cybele, Rhea, and others. That the name Freyja translates to the deliberately ambiguous title of "Lady" infers that like Odin, She wandered and bore more names than are perhaps remembered in the modern age.

Freyja and Frigg

Given the similarities between Frigg and Freyja, with the former as the highest goddess of the Æsir and the latter as the highest goddess of the Vanir, it is perhaps unsurprising that scholars have debated a possible relationship between them. Specifically, many arguments have been made both for and against the idea that Frigg and Freyja are really the same goddess.[7] Some arguments are based on linguistic analyses, others on the fact that Freyja is only mentioned in Northern German (and later Nordic) accounts, while still others center on specific mythic tales. However, both goddesss sometimes appear at the same time in the same text.[8] This final fact would seem to imply that Frigg and Freyja were similar goddesses from different pantheons who, at initial contact, were syncretically conflated with each other, only to be distinguished again at a later date.

Notes

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Schön, Ebbe. (2004). Asa-Tors hammare, Gudar och jättar i tro och tradition. Fält & Hässler, Värnamo. p. 227-228.

- ↑ The writer Johan Alfred Göth, cited in Schön, Ebbe. (2004). Asa-Tors hammare, Gudar och jättar i tro och tradition. Fält & Hässler, Värnamo. p. 227-228.)

- ↑ Translation provided by Wikipedia editors.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Schön, Ebbe. (2004). Asa-Tors hammare, Gudar och jättar i tro och tradition. Fält & Hässler, Värnamo. p. 228.

- ↑ Davidson, 10; Grundy, Stephen, 56-67; Nasstrom, 68-77.

- ↑ Welsh, 75.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Davidson, Hilda Roderick Ellis. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964. ISBN 0317530267.

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- * Egil's Saga. Translated from the Icelandic by Rev. W. C. Green. London: Elliot Stock, 62, Paternoster Row, E.C., 1893. Accessed online at northvegr.org.

- "Grímnismál" in The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. 84-106. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com.

- Grundy, Stephen. "Freyja and Frigg" in Roles of the Northern Goddess. Hilda Ellis Davidson (editor). London: Routlege, 1998. 56-67. ISBN 0415136113.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- "Lokasenna" in The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. 151-173. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Nasstrom, Brit-Mari. "Freyja, A Goddess with Many Names" in The Concept of the Goddess. Edited by Sandra Billington and Miranda Green. London: Routlege, 1996. 68-77. ISBN 0415197899.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- Schön, Ebbe. Asa-Tors hammare, Gudar och jättar i tro och tradition. Värnamo: Fält & Hässler, 2004. ISBN 9189660412.

- Simek, Rudolf. Dictionary of Northern Mythology, Translated by Angela Hall. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1993. ISBN 0859915131.

- Sturlson, Snorri. The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology. Introduced by Sigurdur Nordal; Selected and translated by Jean I. Young. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1954. ISBN 0-520-01231-3.

- Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916. Available online at http://www.northvegr.org/lore/prose/index.php.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. ISBN 0837174201.

- "Völuspá" in The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com.

- Welsh, Lynda. Goddess of the North. York Beach: Weiser Books, 2001. ISBN 157863170X.

[[Category: Religion

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.