Ethology

Ethology is a branch of zoology concerned with the study of animal behavior. Ethologists take a comparative approach, observing one behavior across a variety of species; studies may include topics such as sexual selection, social behavior, kinship, reciprocity and cooperation, parental investment, conflict and aggression.

Methodologically, ethologists engage in hypothesis-driven experimental investigation, often in the field. This combination of lab work with field study reflects an important conceptual underpinning of the discipline: behavior is assumed to be adaptive; i.e., to have evolved in response to the species’ natural environment.

Ethology emerged as a discrete discipline in the 1920s, through the efforts of Konrad Lorenz, Karl von Frisch, and Niko Tinbergen, who were jointly awarded the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their contributions to the study of behavior. Lorenz, von Frisch, and Tinbergen were in turn influenced by the foundational earlier work of, among others, ornithologists Oskar Heinroth and Julian Huxley and the American myrmecologist William Morton Wheeler, who popularized the term ethology (derived from the Greek word for custom) in a seminal 1902 paper.

- One of the key ideas of classical ethology is the concept of fixed action patterns (FAPs). FAPs are instinctive behaviors that will occur reliably in a member of a species in response to an identifiable stimulus from the environment. For example, at the sight of a displaced egg near the next, the greylag goose (Anser anser) will roll the egg back to the others with its beak. If the egg is removed, the animal continues to engage in egg-rolling behavior, pulling its head back as if an imaginary egg is still being maneuvered by the underside of its beak. It will also attempt to move other egg-shaped objects, such as a golf ball, doorknob, or even an egg too large to have been laid by the goose itself (Tinbergen, 1991).

- Another important concept is filial imprinting, a form of learning that occurs in young animals, usually during a critical, sensitive period of their lives. During imprinting, a young animal learns to direct some of its social responses to a particular object, usually a parent.

Despite its valuable contributions to the study of animal behavior, classical ethology also spawned problematic general theories about internal control mechanisms and the extent to which they were genetically hardwired (i.e., innate or instinctive). Models of behavior and motivation have since been revised to account for a more flexible (software?) interaction of environment and genetics.

Although ethology as a disciplinary label has largely faded from use, the desire to understand the animal world has made ethology's intellectual inheritors – such as behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology – rapidly growing fields. Today, students of animal behavior tend to place greater emphasis on social relationships (rather than the animal as individual); however, these studies retain ethology’s tradition of fieldwork and its grounding in evolutionary theory.

Methodology

Tinbergen's four questions for ethologists

The practice of ethological investigation is grounded in the scientific method of hypothesis-driven experimentation. Lorenz's collaborator, Niko Tinbergen, argued that ethologists should consider the following four categories when attempting to formulate a hypothesis that explains any instance of behavior:

- Function: how does the behavior impact the animal's chance of survival and reproduction?

- Mechanism: what are the stimuli that elicit the response? How has the response been modified by recent learning?

- Development: how does the behavior change with age? What early experiences are necessary for the behavior to be demonstrated?

- Evolutionary history: how does the behavior compare with similar behavior in related species? How might the behavior have arisen through the process of phylogeny (the development of the species, genus, or group)?

Using fieldwork to test hypotheses

As an example of how an ethologist might approach a question about animal behavior, consider the study of hearing in an echolocating bat. A species of bat may use frequency chirps to probe the environment while in flight. A traditional neuroscientific study of the auditory system of the bat would involve anesthetizing it, performing a craniotomy to insert recording electrodes in its brain, and then recording neural responses to pure tone stimuli played from loudspeakers. In contrast, an ideal ethological study would attempt to replicate the natural conditions of the animal as closely as possible. It would involve recording from the animal’s brain while it is awake, producing its natural calls while performing a behavior such as insect capture.

Key principles and concepts

Behaviors are adaptive responses to natural selection

Because ethology is understood as a branch of biology, ethologists have been particularly concerned with the evolution of behavior and the understanding of behavior in terms of the theory of natural selection. In one sense, the first modern ethologist was Charles Darwin, whose book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) has influenced many ethologists. (Darwin’s protégé George Romanes became one of the founders of comparative psychology, positing a similarity of cognitive processes and mechanisms between animals and humans.)

Animals use fixed action patterns in communication

As mentioned above, a fixed action pattern (FAP) is an instinctive behavioral sequence produced by a neural network known as the innate releasing mechanism in response to an external sensory stimulus called the sign stimulus or releaser. Once identified by ethologists, FAPs can be compared across species, contrasting similarities and differences in behavior to similarities and differences in form (morphology).

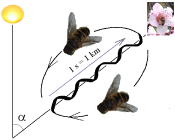

An example of how FAPs work in animal communication is the classic investigation by Austrian ethologist Karl von Frisch of the so-called "dance language" underlying bee communication. The dance is a mechanism for successful foragers to recruit members of the colony to new sources of nectar or pollen.

Imprinting is a behavior involved in learning

Imprinting describes any kind of phase-sensitive learning (i.e., learning occurring at a particular age or life stage) that is rapid and apparently independent of the consequences of behavior. It was first used to describe situations in which an animal or person learns the characteristics of some stimulus, which is therefore said to be "imprinted" onto the subject.

The best known form of imprinting is filial imprinting, in which a young animal learns the characteristics of its parent. Lorenz observed that the young of birds such as geese and chickens spontaneously followed their mothers from almost the first day after they were hatched. Lorenz demonstrated how incubator-hatched geese would imprint on the first suitable moving stimulus they saw within what he called a "critical period" of about 36 hours shortly after hatching. Most famously, the goslings would imprint on Lorenz himself (more specifically, on his wading boots).

Sexual imprinting, which occurs at a later stage of development, is the process by which a young animal learns the characteristics of a desirable mate. For example, male zebra finches appear to prefer mates with the appearance of the female bird that rears them, rather than mates of their own type (Immelmann, 1972).Reverse sexual imprinting is also seen: when two individuals live in close domestic proximity during their early years, both are desensitized to later close sexual attraction and capture-bonding. This phenomenon, known as the Westermarck effect, has probably evolved to suppress inbreeding.

Relation to comparative psychology

In order to summarize the concepts and methods that underlie ethological study, it might be helpful to compare classical ethology to early work in comparative psychology, an alternative approach to the study of animal behavior that also emerged in the early 20th century. The rivalry between these two fields stemmed in part from the disciplinary politcs of academia: ethology, which had developed in Europe, failed to gain a strong foothold in North America, where comparative psychology was dominant.

Broadly speaking, comparative psychology studies general processes, while ethology focuses on adaptive specialization. The two approaches are complementary rather than competitive, but they do lead to different perspectives and sometimes to conflicts of opinion about matters of substance:

- Comparative psychology construes its study as a branch of psychology rather than as an outgrowth of biology. Thus, where comparative psychology sees the study of animal behavior in the context of what is known about human psychology, ethology situates animal behavior in the context of what is known about animal anatomy, physiology, neurobiology, and phylogenetic history.

- Comparative psychologists are interested more in similarities than differences in behavior; they are seeking general laws of behavior, especially relating to development, which could be applied to all animal species, including humans. Hence, early comparative psychologists concentrated on gaining extensive knowledge of the behavior of a handful of species, while ethologists were more interested in gaining knowledge of behavior in a wide range of species in order to be able to make principled comparisons across taxonomic groups.

- Ethologists focus primarily on lab experiments involving a handful of species, mainly rats and pigeons, whereas ethologists concentrated on behavior in natural situations.

Since the 1970s, however, animal behavior has become an integrated discipline, with comparative psychologists and ethological animal behaviorists working on similar problems and publishing side by side in the same journals.

Recent developments in the field

In 1970, the English ethologist John H. Crook published an important paper in which he distinguished comparative ethology from social ethology. He argued that the ethological studies published to date had focused on the former approach—looking at animals as individuals—whereas in the future ethologists would need to concentrate on the social behavior of animal groups.

Since the appearance of E. O. Wilson's seminal book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis in1975, ethology has indeed been much more concerned with the social aspects of behavior, such as phenotypic altruism and cooperation. Research has also been driven by a more sophisticated version of evolutionary theory associated with Wilson and Richard Dawkins.

Furthermore, a substantial rapprochement with comparative psychology has occurred, so the modern scientific study of behavior offers a more or less seamless spectrum of approaches – from animal cognition to more traditional comparative psychology, ethology, and behavioral ecology. Evolutionary psychology, an extension of behavioral ecology, looks at commonalities of cognitive processes in humans and other animals as we might expect natural selection to have shaped them. Another promising subfield is neuroethology, concerned with how the structure and functioning of the brain controls behavior and makes learning possible.

List of influential ethologists

The following list represents a survey of scientists who have made notable contributions to the field of ethology (many are comparative psychologists):

|

|

|

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barnard, C. 2004. Animal Behaviour: Mechanism, Development, Function and Evolution. Harlow, England: Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-130-89936-4

- Tinbergen, N. 1991. The Study of Instinct. Reprint ed. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-198-57722-2

Further reading

- Klein, Z. 2000. The ethological approach to the study of human behaviour. Neuroendocrinology Letters 21:477-81.

External links

- Most popular Internet platform for animal behaviour

- Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognitive Research (KLI)

- Center for the Integrative Study of Animal behaviour (CISAB)

- Introduction to ethology

- Applied Ethology

- The International Society for Human Ethology - aims at promoting ethological perspectives in the scientific study of humans worldwide

- The Four Areas of Biology

- The Four Areas of Biology AND levels of inquiry

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.