Ethology

Ethology (Aethology) (from Greek: ήθος, ethos, "custom"; and λόγος, logos, "knowledge") is the scientific study of animal behavior, and a branch of zoology. A scientist who practices ethology is called an ethologist.

The desire to understand the animal world has made ethology a rapidly growing field, and even since the turn of the 21st century, many prior understandings related to diverse fields such as animal communication, personal symbolic name use, animal emotions, animal culture and learning, and even sexual conduct, long thought to be well understood, have been revolutionized, as have new fields such as neuroethology.

The term "ethology" is derived from the Greek word "ethos" (ήθος), meaning "custom." Other words derived from the Greek word "ethos" include "ethics" and "ethical." The term was first popularized in English by the American myrmecologist William Morton Wheeler in 1902. An earlier, slightly different sense of the term was proposed by John Stuart Mill in his 1843 System of Logic. He recommended the development of a new science, "ethology," whose purpose would be the explanation of individual and national differences in character, on the basis of associationistic psychology. This use of the word for this purpose was never adopted.

Relation to comparative psychology

Comparative psychology also studies animal behaviour, but, as opposed to ethology, construes its study as a branch of psychology rather than as one of biology. Thus, where comparative psychology sees the study of animal behaviour in the context of what is known about human psychology, ethology sees the study of animal behaviour in the context of what is known about animal anatomy, physiology, neurobiology, and phylogenetic history. Furthermore, early comparative psychologists concentrated on the study of learning and tended to look at behaviour in artificial situations, whereas early ethologists concentrated on behaviour in natural situations, tending to describe it as instinctive. The two approaches are complementary rather than competitive, but they do lead to different perspectives and sometimes to conflicts of opinion about matters of substance. In addition, for most of the twentieth century, comparative psychology developed most strongly in North America, while ethology was stronger in Europe, and this led to different emphases as well as somewhat differing philosophical underpinnings in the two disciplines. A practical difference is that early comparative psychologists concentrated on gaining extensive knowledge of the behaviour of very few species, while ethologists were more interested in gaining knowledge of behaviour in a wide range of species in order to be able to make principled comparisons across taxonomic groups. Ethologists have made much more use of a truly comparative method than comparative psychologists ever have. Despite the historical divergence, most ethologists (as opposed to behavioural ecologists), at least in North America, teach in psychology departments.

The influence of Darwinism

Because ethology is understood as a branch of biology, ethologists have been particularly concerned with the evolution of behaviour and the understanding of behaviour in terms of the theory of natural selection. In one sense, the first modern ethologist was Charles Darwin, whose book, The expression of the emotions in animals and men, has influenced many ethologists. He pursued his interest in behaviour by encouraging his protégé George Romanes, who investigated animal learning and intelligence using an anthropomorphic method, anecdotal cognitivism, that did not gain scientific support (one of the founders of comparative psychology, positing a similarity of cog processes and mechanisms between animals and humans.

Key principles

Other early ethologists, such as Oskar Heinroth and Julian Huxley, instead concentrated on behaviours that can be called instinctive, or natural, in that they occur in all members of a species under specified circumstances. Their first step in studying the behaviour of a new species was to construct an ethogram (a description of the main types of natural behaviour with their frequencies of occurrence). This approach provided an objective, cumulative base of data about behaviour, which subsequent researchers could check and build on.

Methodology

Neuroethology is a branch of neuroscience that emphasizes the study of neural mechanisms of natural behavior. This is in contrast to other approaches to neuroscience that study the nervous system in isolation, or in the context of artificial conditions. The term itself is a combination of the words neurophysiology and ethology (Pfluger 1999).

As an example, consider the study of hearing in an echolocating bat. A species of bat may use frequency chirps to probe the environment while in flight. A traditional neuroscience study of the auditory system of the bat would involve anesthetizing it, performing a craniotomy to insert recording electrodes in its brain, and then recording neural responses to pure tone stimuli played from loudspeakers. In contrast, an ideal neuroethological study would attempt to replicate the natural conditions of the animal as closely as possible. It would involve recording from the animals brain while it is awake, producing its natural calls while performing some natural behavior such as insect capture.

The fixed action pattern and animal communication

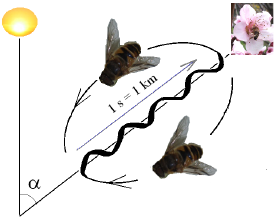

An important step, associated with the name of Konrad Lorenz though probably due more to his teacher, Oskar Heinroth, was the identification of fixed action patterns (FAPs). Lorenz popularized FAPs as instinctive responses that would occur reliably in the presence of identifiable stimuli (called sign stimuli or releasing stimuli). These FAPs could then be compared across species, and the similarities and differences between behaviour could be easily compared with the similarities and differences in morphology. An important and much quoted study of the Anatidae (ducks and geese) by Heinroth used this technique. The ethologists noted that the stimuli that released FAPs were commonly features of the appearance or behaviour of other members of their own species, and they were able to show how important forms of animal communication could be mediated by a few simple FAPs. The most sophisticated investigation of this kind was the study by Karl von Frisch of the so-called "dance language" underlying bee communication. Lorenz developed an interesting theory of the evolution of animal communication based on his observations of the nature of fixed action patterns and the circumstances in which animals emit them.

Waggle dance is a term used in beekeeping and ethology for a particular figure-eight dance of the honeybee. By performing this dance, successful foragers can share with their hive mates information about the direction and distance to patches of flowers yielding nectar or pollen, or both, and to water sources. Thus the waggle dance is a mechanism whereby successful foragers can recruit other bees in their colony to good locations for collecting various resources. It used to be thought that bees have two distinct recruitment dances—round dances and waggle dances—the former for indicating nearby targets and the latter for indicating distant target, but it is now known that a round dance is simply a waggle dance with a very short waggle run (see below). Austrian ethologist Karl von Frisch was one of the first who translated the meaning of the waggle dance.

In ethology, a fixed action pattern (FAP) is an instinctive behavioral sequence that is indivisible and runs to completion. Fixed action patterns are invariant and are produced by a neural network known as the innate releasing mechanism in response to an external sensory stimulus known as a sign stimulus or releaser (a signal from one individual to another).

Examples

A mating dance may be used as an example. Many species of birds engage in a specific series of elaborate movements, usually by a brightly colored male. How well they perform the "dance" is then used by females of the species to judge their fitness as a potential mate. The key stimulus is typically the presence of the female.

Another example of a FAP is the red-bellied stickleback (fish). The male turns a bright red/blue colour during the breeding season. This colour change is the fixed action pattern in response to an increasing day length which is the sign stimulus. During this time they are also naturally aggressive towards other red-bellied sticklebacks, another FAP. However anything that is red will bring about this FAP. The proximate response to this is that due to the stimuli, a nerve sends a signal to attack that red item. The ultimate cause of this behavior stems from the fact that the stickleback needs the area in which it is living for either habitat, food, mating with other sticklebacks, or other purposes. This interaction was studied by Niko Tinbergen.

Another well known case is the classic experiments by Tinbergen and Lorenz on the Graylag Goose. Like similar waterfowl, it will roll a displaced egg near its nest back to the others with its beak. The sight of the displaced egg triggers this mechanism. If the egg is taken away, the animal continues with the behavior, pulling its head back as if an imaginary egg is still being maneuvered by the underside of its beak. However, it will also attempt to move other egg shaped objects, such as a golf ball, door knob, or even an egg too large to have possibly been laid by the goose itself (a supernormal stimulus).[1]

Although fixed action patterns are most common in animals with simpler cognitive capabilities, humans also demonstrate fixed action patterns. For example, infants grasp strongly with their hands as a response to tactile stimulus. This is thought to be a vestigial mechanism where when threatened by a predator a young primate would grab on to a parent's fur so the parent could climb to safety without having to hold its child[citation needed] (see also reflex action). Another FAP shared by some animals, including humans, is yawning, which often triggers yawning in other individuals. Yawns last around 6 seconds and are difficult to stop once initiated. Yawning, whether seen, heard or both, then serves as a releaser in nearby animals.[2]

Imprinting

A second important finding of Lorenz concerned the early learning of young nidifugous birds, a process he called imprinting. Lorenz observed that the young of birds such as geese and chickens spontaneously followed their mothers from almost the first day after they were hatched, and he discovered that this response could be imitated by an arbitrary stimulus if the eggs were incubated artificially and the stimulus was presented during a critical period (a less temporally constrained period is called a sensitive period) that continued for a few days after hatching.

Imprinting' is the term used in psychology and ethology to describe any kind of phase-sensitive learning (learning occurring at a particular age or a particular life stage) that is rapid and apparently independent of the consequences of behavior. It was first used to describe situations in which an animal or person learns the characteristics of some stimulus, which is therefore said to be "imprinted" onto the subject.

The best known form of imprinting is filial imprinting, in which a young animal learns the characteristics of its parent. It is most obvious in nidifugous birds, who imprint on their parents and then follow them around. It was first reported in domestic chickens, by the 19th century amateur biologist Douglas Spalding. It was rediscovered by the early ethologist Oskar Heinroth, and studied extensively and popularised by his disciple Konrad Lorenz working with greylag geese. Lorenz demonstrated how incubator-hatched geese would imprint on the first suitable moving stimulus they saw within what he called a "critical period" of about 36 hours shortly after hatching. Most famously, the goslings would imprint on Lorenz himself (more specifically, on his wading boots), and he is often depicted being followed by a gaggle of geese who had imprinted on him. Filial imprinting is not restricted to animals that are able to follow their parents, however; in child development the term is used to refer to the process by which a baby learns who its mother and father are. The process is recognised as beginning in the womb, when the unborn baby starts to recognise its parents' voices (Kissilevsky et al, 2003).

Tinbergen's four questions for ethologists

Lorenz's collaborator, Niko Tinbergen, argued that ethology always needed to pay attention to four kinds of explanation in any instance of behaviour:

- Function: how does the behaviour impact on the animal's chances of survival and reproduction?

- Causation: what are the stimuli that elicit the response, and how has it been modified by recent learning?

- Development: how does the behaviour change with age, and what early experiences are necessary for the behaviour to be shown?

- Evolutionary history: how does the behaviour compare with similar behaviour in related species, and how might it have arisen through the process of phylogeny?

The history of ethology

Lorenz, Tinbergen, and von Frisch were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in 1972 for their work in developing ethology.

Recent developments in the field

In 1970, the English ethologist John H. Crook published an important paper in which he distinguished comparative ethology from social ethology, and argued that much of the ethology that had existed so far was really comparative ethology—looking at animals as individuals—whereas in the future ethologists would need to concentrate on the behaviour of social groups of animals and the social structure within them.

Indeed, E. O. Wilson's book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis appeared in 1975, and since that time the study of behaviour has been much more concerned with social aspects. It has also been driven by the stronger, but more sophisticated, Darwinism associated with Wilson and Richard Dawkins. The related development of behavioural ecology has also helped transform ethology. Furthermore, a substantial rapprochement with comparative psychology has occurred, so the modern scientific study of behaviour offers a more or less seamless spectrum of approaches – from animal cognition to more traditional comparative psychology, ethology, sociobiology and behavioural ecology. Sociobiology has more recently developed into evolutionary psychology.

"Super-real object" is an object that causes an abnormally strong response in an animal. An example of this is the design of dummies that mimic and over-stress the key characteristics of individuals in certain species causing animals to direct behaviour to the super-real object and ignore the real object. A super-real object may cause pathologies and we can see many examples in humans (super-sweet food, super-big female traits, super-relaxing drugs, etc.). See the book, Foundations of Ethology by Konrad Lorenz.

List of ethologists

People who have made notable contributions to the field of ethology (many are comparative psychologists):{| width=100% | valign=top width=33% |

- Robert Ardrey

- George Barlow

- Patrick Bateson

- John Bowlby

- Colleen Cassady St. Clair

- Raymond Coppinger

- John H. Crook

- Marian Stamp Dawkins

- Richard Dawkins

- Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt

- John Fentress

- Dian Fossey

| valign=top width=34% |

- Karl von Frisch

- Jane Goodall

- Oskar Heinroth

- Robert Hinde

- Julian Huxley

- Lynne Isbell

- Julian Jaynes

- Erich Klinghammer

- Peter Klopfer

- Otto Koehler

- Paul Leyhausen

- Konrad Lorenz

| valign=top width=33% |

- Aubrey Manning

- Eugene Marais

- Patricia McConnell

- Desmond Morris

- George Romanes

- B. F. Skinner

- William Homan Thorpe

- Niko Tinbergen

- Jakob von Uexküll

- Frans de Waal

- William Morton Wheeler

- E. O. Wilson

|}

See also

- Altruism in animals

- Animal cognition

- Animal communication

- Anthrozoology

- Cognitive ethology

- Emotion in animals

- Important publications in ethology

- Non-human animal sexuality

- Phylogenetic comparative methods

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barnard, C. 2004. Animal Behaviour: Mechanism, Development, Function and Evolution. Harlow, England: Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-130-89936-4

Further reading

- Klein, Z. (2000). The ethological approach to the study of human behaviour. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 21, 477-481. Full text

External links

- Most popular Internet platform for animal behaviour

- Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognitive Research (KLI)

- Center for the Integrative Study of Animal behaviour (CISAB)

- Introduction to ethology

- Applied Ethology

- The International Society for Human Ethology - aims at promoting ethological perspectives in the scientific study of humans worldwide

Diagrams on Tinbergen's four questions

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Tinbergen, N. (1951) The Study of Instinct. Oxford University Press, New York.

- ↑ Provine, R. R. (1986) Yawning as a stereo-typed action pattern and releasing stimulus. Ethology 72:109-122.