Edward Jenner

Edward B. Jenner (May 17, 1749 – January 26, 1823) was an English physician and scientist who is most recognized for introducing and popularizing an effective and relatively safe means of vaccination against smallpox, a discovery that proved to be one of the most significant medical breakthroughs of all time.

Although inoculations using dried smallpox secretions had been known for centuries in China and had spread to the Ottoman Empire and then England before Jenner’s time, his vaccine utilizing material from a cowpox lesion was safer, more effective, and without the risk of smallpox transmission. Vaccination to prevent smallpox was soon practiced all over the world. Eventually, a disease that had killed many hundreds of millions, and disfigured and blinded countless more, was completely eradicated. It is the only infectious disease in humans that has been completely eradicated.

Jenner also coined the term immunization, which in its original meaning specifically referred to the protection conferred against smallpox using material from cowpox virus. Jenner called the material used for inoculation vaccine, from the root word vacca, which is Latin for cow.

Jenner also was a naturalist, who studied his natural surroundings in Berkeley, Gloucestershire in rural England; was a horticulturist; and discovered the fossils of a plesiosaur. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society based on his study of the nesting habits of the cuckoo.

Although Jenner was not the first to discover the practice of inoculation, and even the use of cowpox vaccine is believed to have been used by a Dorset farmer, Jenner's leadership and intellectual qualities lead to systematically developing, testing, and popularizing this method that saved countless lives. Ironically, the first experiment he performed, on a young boy, would be considered unethical by current standards, but lead to major benefit for humanity.

Early life

Jenner trained in Chipping Sodbury, Gloucestershire as an apprentice to John Ludlow, a surgeon, for eight years from the age of 13. In 1770, Jenner went up to London to study surgery and anatomy under the surgeon John Hunter and others at St George's, University of London. Hunter was the preeminent medical teacher in Britain (Last 2002), a noted experimentalist, and later a fellow of the Royal Society.

William Osler records that Jenner was a student to whom Hunter repeated William Harvey's advice, very famous in medical circles (and characteristically Enlightenment), "Don't think, try." Jenner, therefore, was noticed early by men famous for advancing the practice and institutions of medicine. Hunter remained in correspondence with him over natural history and proposed him for the Royal Society. Returning to his native countryside by 1773, he became a successful general practitioner and surgeon, practicing in purpose-built premises at Berkeley.

Jenner and others formed a medical society in Rodborough, Gloucestershire, meeting to read papers on medical subjects and dine together. Jenner contributed papers on angina pectoris, ophthalmia, and valvular disease of the heart and commented on cowpox. He also belonged to a similar society which met in Alveston, near Bristol (RCP).

He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1788, following a careful study combining observation, experiment, and dissection into a description of the previously misunderstood life of the cuckoo in the nest.

Jenner's description of the newly-hatched cuckoo pushing it's host's eggs and fledglings from the nest was confirmed in the 20th century (JM) when photography became feasible. Having observed the behavior, he demonstrated an anatomical adaptation for it—the baby cuckoo has a depression in its back that is not present after 12 days of life, in which it cups eggs and other chicks to push them out of the nest. It had been assumed that the adult bird did this but the adult does not remain in the area for sufficiently long. His findings were published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1787.

He married Catherine Kingscote (died 1815 from tuberculosis) in March 1788 having met her when balloons were hot science, and he and other Fellows were experimenting with them. His trial balloon descended into Kingscote Park, owned by Anthony Kingscote, Catherine being one of his three daughters.

Jenner did not take any examinations to receive his medical degree, but purchased a medical degree in 1792 from a Scottish University, the University of St. Andrews, and subsequently would apply for a degree from Oxford University, which he was granted (Last 2002).

Smallpox

Smallpox is a very deadly disease, that is estimated to have killed 400,000 Europeans each year during the 18th century (including five reigning monarchs), and was responsible for a third of all blindness (Behbehani 1983). Between 20 to 60 percent of all those infected—and over 80% of infected children—died from the disease (Riedel 2005). During the 20th century, it is estimated that smallpox was responsible for 300–500 million deaths (Koplow 2003).

Although innoculations against smallpox have been known from around 1000 C.E. in China, and was known in the Ottoman Emp;ire in Jenner's time, Jenner's work using cowpox lead to widespread innoculaitons against the dreaded disease of smallpox.

one of the most important medical discoveries of all time..

process of conferring increased resistance to an infectious disease by a means other than experiencing the natural infection. Typically, this involves exposure to an agent (antigen or immunogen) that is designed to fortify the person's immune system against that agent or similar infectious agents (active immunization). Immunization also can include providing the subject with protective antibodies developed by someone else or another organism (passive immunization).

When the human immune system is exposed to a disease once, it can develop the ability to quickly respond to a subsequent infection. Therefore, by exposing an individual to an immunogen in a controlled way, the person's body will then be able to protect itself from infection later on in life.

Recognizing that an infectious disease, once overcome, did not normally reappear, people have tried to prevent getting a disease by purposely inoculating themselves with infected material. This is first known with smallpox (NMAH 2007) before 200 B.C.E. (NMAH 2007). National Museum of American History (NMAH). 2007. History of vaccines. Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Retrieved September 18, 2007.

conferred against smallpox by material taken from cow infected with Cowpox virus, which is related to the vaccinia virus (Blakemore and Jennett 2001).

In 1718, Lady Mary Wortley Montague reported that the Turks have a habit of deliberately inoculating themselves with fluid taken from mild cases of smallpox and she inoculated her own children (Behbehani 1983).

While vaccination is used today in the same sense as immunization, in a strict sense the term refers to its original meaning, which is protection conferred against smallpox by material taken from cow infected with Cowpox virus, which is related to the vaccinia virus (Blakemore and Jennett 2001).

Smallpox is believed to have emerged in human populations about 10,000 B.C.E.[2] The disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans each year during the 18th century (including five reigning monarchs), and was responsible for a third of all blindness.[3] Between 20 and 60% of all those infected—and over 80% of infected children—died from the disease

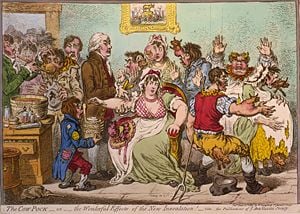

Around this time smallpox was greatly feared, as one in three of those who contracted the disease died, and those who survived were often badly disfigured. Voltaire, a few years later, recorded that 60.243% of people caught smallpox, with 20% of the population dying of it. In the years following 1770 there were at least six people in England and Germany (Sevel, Jensen, Jesty 1774, Rendall, Plett 1791) who had successfully tested the possibility of using the cowpox vaccine as an immunisation for smallpox in humans. [1] For example, Dorset farmer, Benjamin Jesty, had successfully induced immunity in his wife and two children with cowpox during a smallpox epidemic in 1774, but it was not until Jenner's work some twenty years later that the procedure became widely understood. Indeed it is generally believed that Jenner was unaware of Jesty's success and arrived at his conclusions independently.[citation needed]

In 1796, Edward Jenner (1749-1823) inoculated against smallpox using cowpox (a mild relative of the deadly smallpox virus). While Edward Jenner has been recognized as the first doctor to give sophisticated immunization, it was British dairy farmer Benjamin Jestey who noticed that "milkmaids" did not become infected with smallpox, or displayed a milder form. Jestey took the pus from an infected cow's udder and inoculated his wife and children with cowpox, in order to artificially induce immunity to smallpox during the epidemic of 1774, thereby making them immune to smallpox. Twenty-two years later, by injecting a human with the cowpox virus (which was harmless to humans), Jenner swiftly found that the immunized human was then also immune to smallpox. The process spread quickly, and the use of cowpox immunization and later the vaccinia virus (of the same family as the cowpox virus and the smallpox virus or Variola) led to the almost total eradication of smallpox in modern human society. After successful vaccination campaigns throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the World Health Organization (WHO) certified the eradication of smallpox in 1979.

Vaccination to prevent smallpox was soon practiced all over the world. During the 19th century, the cowpox virus used for smallpox vaccination was replaced by vaccinia virus. Vaccinia is in the same family as cowpox and variola but is genetically distinct from both.

| Jenner's Initial Theory |

| In fact he thought the initial source of infection was a disease of horses, called "the grease", and that this was transferred to cows by farmworkers, transformed, and then manifested as cowpox. From that point on he was correct, the complication probably arose from coincidence. |

Noting the common observation that milkmaids did not generally get smallpox, Jenner theorized that the pus in the blisters which milkmaids received from cowpox (a disease similar to smallpox, but much less virulent) protected the milkmaids from smallpox. He may have had the advantage of hearing stories of Benjamin Jesty and perhaps others deliberately arranging cowpox infection of their families and of a reduced risk in those families.

On 14 May 1796, Jenner tested his theory by inoculating James Phipps, a young boy of 8 years old, with material from the cowpox blisters of the hand of Sarah Nelmes, a milkmaid who had caught cowpox from a cow called Blossom[2], whose hide hangs on the wall of the library at St George's medical school (now in Tooting), in commemoration of one of the school's most renowned alumni. Phipps was the 17th case described in Jenner's first paper on vaccination.

Jenner inoculated Phipps with cowpox pus in both arms on one day, by scraping the pus from Nelmes' blisters onto a piece of wood then transferring this to Phipps' arms. This produced a fever and some uneasiness but no great illness. Later, he injected Phipps with variolous material, which would have been the routine attempt to produce immunity at that time. No disease followed. Jenner reported that later the boy was again challenged with variolacious material and again showed no sign of infection.

|

Known: that smallpox was more dangerous than variolation and cowpox less dangerous than variolation. |

| The hypothesis tested: That infection with cowpox would give immunity to smallpox. |

|

The test: If variolation failed to produce an infection, Phipps was shown to be immune to smallpox. |

|

The consequence: Immunity to smallpox could be induced much more safely. |

He continued his research and reported it to the Royal Society, who did not publish the initial report. After improvement and further work, he published a report of twenty-three cases. Some of his conclusions were correct, and some erroneous—modern microbiological and microscopic methods would make this easier to repeat. The medical establishment, as cautious then as now, considered his findings for some time before accepting them. Eventually vaccination was accepted, and in 1840 the British government banned variolation and provided vaccination free of charge. (See Vaccination acts)

Jenner's continuing work on vaccination prevented his continuing his ordinary medical practice. He was supported by his colleagues and the King in petitioning Parliament and was granted £10,000 for his work on vaccination. In 1806 he was granted another £20,000 for his continuing work.

In 1803 in London he became involved with the Jennerian Institution, a society concerned with promoting vaccination to eradicate smallpox. In 1808, with government aid, this society became the National Vaccine Establishment. Jenner became a member of the Medical and Chirurgical Society on its foundation in 1805, and subsequently presented to them a number of papers. This is now the Royal Society of Medicine.

Returning to London in 1811 he observed a significant number of cases of smallpox after vaccination occurring. He found that in these cases the severity of the illness was notably diminished by the previous vaccination. In 1821 he was appointed Physician Extraordinary to King George IV, a considerable national honour, and was made Mayor of Berkeley and Justice of the Peace. He continued his interests in natural history. In 1823, the last year of his life, he presented his Observations on the Migration of Birds to the Royal Society.

He was found in a state of apoplexy on 25 January 1823, with his right side paralysed. He never rallied, and died of what was apparently a stroke (he had suffered a previous stroke) on 26 January 1823, aged 73. He was survived by one son and one daughter, his elder son having died of tuberculosis at the age of 21.

Legacy

In 1980, the World Health Organization declared smallpox an eradicated disease. This was the result of coordinated public health efforts by many people, but vaccination was an essential component. Although it was declared eradicated, some samples still remain in laboratories in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia in the United States, and State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR in Koltsovo, Novosibirsk Oblast, Russia.

Monuments

- Jenner's house is now a small museum housing among other things the horns of the cow, Blossom. It lies in the Gloucestershire village of Berkeley.

- The word vaccination comes from the Latin vaccinia, cowpox, from vacca, cow.

- Jenner was buried in the chancel of the parish church of Berkeley.

- A statue, by Robert William Sievier, was erected in the nave of Gloucester Cathedral.

- A statue was erected in Trafalgar Square, later moved to Kensington Gardens.[3]

- Near the small Gloucestershire village of Uley, Downham Hill is locally known as 'Smallpox Hill', with a possible connection to Jenner's local work with the disease.[citation needed]

- St George's, University of London has a wing named after him as well as a bust of him.[4]

- A small grouping of villages in Somerset County, Pennsylvania, United States, were named in honour of Jenner by early 19th century English settlers, including what are now the towns of Jenners, Jenner Township, Jenner Crossroads and Jennerstown, Pennsylvania.

Publications

- 1798 An Inquiry Into the Causes and Effects of the Variolæ Vaccinæ

- 1799 Further Observations on the Variolœ Vaccinœ

- 1800 A Continuation of Facts and Observations relative to the Variolœ Vaccinœ 40pgs

- 1801 The Origin of the Vaccine Inoculation 12pgs

See also

- Vaccine

- Vaccination

- Inoculation

- History of science

Footnotes

- ↑ Plett PC (2006)."[Peter Plett and other discoverers of cowpox vaccination before Edward Jenner]" (in German). Sudhoffs Arch 90 (2): 219–32.

- ↑ , http://www.jennermuseum.com/sv/smallpox2.shtml Edward Jenner Museum]

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJennerArchivesRCP - ↑ St George's, University of London. Our History.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Behbehani, A. M. 1983. The smallpox story: Life and death of an old disease. Microbiol Rev 47(4): 455-509. PMID 6319980.

- Blakemore, C., and S. Jennett. 2001. The Oxford Companion to the Body. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019852403X.

- Hinman, A. R.. 2002. Immunization. In L Breslow, Encyclopedia of Public Health. New York: Macmillan Reference USA/Gale Group Thomson Learning. ISBN 0028658884.

n.d. [1]

Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

- Papers at the Royal College of Physicians

- Baron, John M.D. F.R.S., "The Life of Edward Jenner MD LLD FRS", Henry Colburn, London, 1827.

- Edward Jenner, the man and his work. BMJ 1949 E Ashworth Underwood

- Cartwright, Keith (2005), "From Jenner to modern smallpox vaccines.", Occupational medicine (Oxford, England) 55 (7): 563, PMID:16251374

- Riedel, Stefan (2005), "Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination.", Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) 18 (1): 21-5, PMID:16200144

- Tan, S Y (2004), "Edward Jenner (1749-1823): conqueror of smallpox.", Singapore medical journal 45 (11): 507-8, PMID:15510320

- van Oss, C J (2000), "Inoculation against smallpox as the precursor to vaccination.", Immunol. Invest. 29 (4): 443-6, PMID:11130785

- Gross, C P & K A Sepkowitz, "The myth of the medical breakthrough: smallpox, vaccination, and Jenner reconsidered.", Int. J. Infect. Dis. 3 (1): 54-60, PMID:9831677

- Willis, N J (1997), "Edward Jenner and the eradication of smallpox.", Scottish medical journal 42 (4): 118-21, PMID:9507590

- Theves, G (1997), "[Smallpox: an historical review]", Bulletin de la Société des sciences médicales du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg 134 (1): 31-51, PMID:9303824

- Kempa, M E (1996), "[Edward Jenner (1749-1823)—benefactor to mankind (100th anniversary of the first vaccination against smallpox)]", Pol. Merkur. Lekarski 1 (6): 433-4, PMID:9273243

- Baxby, D (1996), "The Jenner bicentenary: the introduction and early distribution of smallpox vaccine.", FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 16 (1): 1-10, PMID:8954347

- Larner, A J (1996), "Smallpox.", N. Engl. J. Med. 335 (12): 901; author reply 902, PMID:8778627

- Aly, A & S Aly (1996), "Smallpox.", N. Engl. J. Med. 335 (12): 900-1; author reply 902, PMID:8778626

- Magner, J (1996), "Smallpox.", N. Engl. J. Med. 335 (12): 900, PMID:8778624

- Kumate-Rodríguez, J, "[Bicentennial of smallpox vaccine: experiences and lessons]", Salud pública de México 38 (5): 379-85, PMID:9092091

- Budai, J (1996), "[200th anniversary of the Jenner smallpox vaccine]", Orvosi hetilap 137 (34): 1875-7, PMID:8927342

- Rathbone, J (1996), "Lady Mary Wortley Montague's contribution to the eradication of smallpox.", Lancet 347 (9014): 1566, PMID:8684145

- Baxby, D (1996), "The Jenner bicentenary; still uses for smallpox vaccine.", Epidemiol. Infect. 116 (3): 231-4, PMID:8666065

- Cook, G C (1996), "Dr William Woodville (1752-1805) and the St Pancras Smallpox Hospital.", Journal of medical biography 4 (2): 71-8, PMID:11616267

- Baxby, D, "Jenner and the control of smallpox.", Transactions of the Medical Society of London 113: 18-22, PMID:10326082

- Dunn, P M (1996), "Dr Edward Jenner (1749-1823) of Berkeley, and vaccination against smallpox.", Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 74 (1): F77-8, PMID:8653442

- Meynell, E (1995), "French reactions to Jenner's discovery of smallpox vaccination: the primary sources.", Social history of medicine : the journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine / SSHM 8 (2): 285-303, PMID:11639810

- Bloch, H (1993), "Edward Jenner (1749-1823). The history and effects of smallpox, inoculation, and vaccination.", Am. J. Dis. Child. 147 (7): 772-4, PMID:8322750

- Roses, D F (1992), "From Hunter and the Great Pox to Jenner and smallpox.", Surgery, gynecology & obstetrics 175 (4): 365-72, PMID:1411896

- Turk, J L & E Allen (1990), "The influence of John Hunter's inoculation practice on Edward Jenner's discovery of vaccination against smallpox.", Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 83 (4): 266-7, PMID:2187990

- Poliakov, V E (1985), "[Edward Jenner and vaccination against smallpox]", Meditsinskaia sestra 44 (12): 49-51, PMID:3912642

- Hammarsten, J F; W Tattersall & J E Hammarsten (1979), "Who discovered smallpox vaccination? Edward Jenner or Benjamin Jesty?", Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 90: 44-55, PMID:390826

- Rodrigues, B A (1975), "Smallpox eradication in the Americas.", Bulletin of the Pan American Health Organization 9 (1): 53-68, PMID:167890

- Wynder, E L (1974), "A corner of history: Jenner and his smallpox vaccine.", Preventive medicine 3 (1): 173-5, PMID:4592685

- Andreae, H (1973), "[Edward Jenner, initiator of cowpox vaccination against human smallpox, died 150 years ago]", Das Offentliche Gesundheitswesen 35 (6): 366-7, PMID:4269783

- Friedrich, I (1973), "[A cure for smallpox. On the 150th anniversary of Edward Jenner's death]", Orvosi hetilap 114 (6): 336-8, PMID:4567814

- MacNalty, A S (1968), "The prevention of smallpox: from Edward Jenner to Monckton Copeman.", Medical history 12 (1): 1-18, PMID:4867646

- Udovitskaia, E F (1966), "[Edward Jenner and the history of his scientific achievement. (On the 170th anniversary of the discovery of smallpox vaccination)]", Vrachebnoe delo 11: 111-5, PMID:4885910

- VOIGT, K (1964), "[THE PHARMACY DISPLAY WINDOW. EDWARD JENNER DISCOVERED SMALLPOX VACCINATION.]", Pharmazeutische Praxis 106: 88-9, PMID:14237138

External links

- "EDWARD JENNER." LoveToKnow 1911 Online Encyclopedia. © 2003, 2004 LoveToKnow.

- Jenner's papers on vaccination: http://www.bartleby.com/38/4/

- A digitized copy of An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolµ vaccinµ (1798), from the Posner Memorial Collection at Carnegie Mellon

- The Jenner Museum: http://www.dursley-cotswolds-uk.com/Jenner%20museum.html

- The Jenner Museum: http://www.jennermuseum.com

- The Evolution of Modern Medicine. Osler, W

- "The First Vaccination" Painting by Georges Gaston Melingue

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Jenner, Edward |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | English doctor, introduced and studied the smallpox vaccine |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 17 May 17 1749 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Gloucestershire |

| DATE OF DEATH | 26 January 1823 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ The Jenner Museum. Edward Jenner and the Cuckoo.

- ↑ Riedel S (2005). Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 18 (1): 21–5.