Difference between revisions of "Dominican Order" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (42 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| + | [[Image:SaintDominic.jpg|right|thumb|200px|[[Saint Dominic]] saw the need for a new type of organization to address the needs of his time.]] | ||

| − | + | The '''Dominican Order''', originally known as the '''Order of Preachers''', is a [[Roman Catholic religious order|Catholic religious order]] created by [[Saint Dominic]] in the early [[thirteenth century]] in [[France]]. Dominic established his religious community in [[Toulouse]] in 1214, officially recognized as an order by [[Pope Honorius III]] in 1216. Founded under the [[Augustinian]] rule, the Dominican Order is one of the great orders of [[mendicant Orders|mendicant friars]] that revolutionized religious life in [[Europe]] during the [[High Middle Ages]]. However, it notably differed from the Franciscan Order in its attitude toward ecclesiastical [[poverty]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Established to preach the [[Gospel]] and to combat [[heresy]], the order is famed for its intellectual tradition, having produced many leading theologians and philosophers. It played a leading role in investigating and prosecuting heresy during the Inquisition. Important [[Dominicans]] include [[Saint Dominic]], St. [[Thomas Aquinas]], [[Albertus Magnus]], St. [[Catherine of Siena]], and [[Girolamo Savonarola]]. Four Dominican [[Cardinal (Catholicism)|cardinal]]s have become popes. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In [[England]] and some other countries the Dominicans are referred to as | + | In [[England]] and some other countries the Dominicans are referred to as [[Blackfriars]] on account of the black ''cappa'' or cloak they wear over their white [[Religious habit|habits]]. In [[France]], the Dominicans are also known as [[Jacobins]], because their first convent in [[Paris]] bore the name "Saint Jacques," or ''Jacobus'' in Latin. They have also been referred to using a Latin pun, as "Domini canes," or "The Hounds of God," a reference to the order's reputation as most obedient servants of the faith, sometimes with a negative connotation or reference to the order's involvement with the [[Inquisition]]. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | The Dominican Order is headed by the [[Master of the Order of Preachers|Master of the Order]], who is currently Brother [[Carlos Azpiroz Costa]]. Members of the order often carry the letters [[O.P.]] after their name. | |

==Foundation of the Order== | ==Foundation of the Order== | ||

| − | + | Dominic saw the need to establish a new kind of order when traveling through the south of [[France]] when that region was the stronghold of heretical [[Albigensian]] thought—also known as [[Cathar]]ism—centered around the town of [[Albi]].<ref>Catharism was a name given to a religious sect with gnostic elements that appeared in the Languedoc region of France in the eleventh century and flourished in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Catharism had its roots in the Paulician movement in Armenia and was also influenced by the Bogomiles with whom the Paulicians eventually merged. They also became influenced by dualist and perhaps Manichaean beliefs.</ref> To combat [[heresy]] and other problems in urban areas, he sought to establish an order that would bring the systematic education of the older monastic orders such as the [[Benedictine]]s to bear on the religious problems of the burgeoning population of cities. His was to be a [[preaching]] order, trained to preach in the [[vernacular]] languages, but with a sound background in academic [[theology]]. Rather than earning their living on vast farms as the monasteries had done, the new friars would survive by persuasive preaching and the alms-giving of those who heard them. They were initially scorned by more traditional orders, who thought these "urban monks" would never survive the temptations of the city. | |

| − | + | The Dominicans were thus set up as the branch of the [[Catholicism|Catholocism]] Church to deal with heresy. The organization of the Order of Preachers was approved in December 1216 by [[Pope Honorius III]]. | |

| − | + | ==History of the Order== | |

| + | ===Middle Ages=== | ||

| + | The thirteenth century is the classic age of the order. It reached all classes of Christian society fighting [[Christian heresy|heresy]], [[Schism (religion)|schism]], and [[paganism]]. Its schools spread throughout the entire Church. Its doctors wrote monumental works in all branches of knowledge and two among them, [[Albertus Magnus]], and especially [[Thomas Aquinas]], founded a school of philosophy and theology which was to rule the ages to come in the life of the Church. | ||

| − | + | An enormous number of its members held offices in both Church and state—as popes, cardinals, bishops, legates, inquisitors, confessors of princes, ambassadors, and ''paciarii'' (enforcers of the peace decreed by popes or councils). A period of relaxation ensued during the [[fourteenth century]] owing to the general decline of Christian society. The weakening of doctrinal activity favored the development of the [[ascetic]] and [[contemplative]] life sprang up, especially in [[Germany]] and [[Italy]], an intense and exuberant mysticism with which the names of [[Meister Eckhart]], [[Heinrich Suso]], [[Johannes Tauler]], and [[Catherine of Siena|St. Catherine of Siena]] are associated, which has also been called "Dominican mysticism." This movement was the prelude to the reforms undertaken at the end of the century, by [[Raimondo delle Vigne|Raymond of Capua]], and continued in the following century. It assumed remarkable proportions in the congregations of [[Lombardy]] and the [[Netherlands]], and in the reforms of [[Girolamo Savonarola]] at [[Florence]]. | |

| − | + | Savonarola, an Italian Dominican priest and leader of Florence from 1494 until his execution in 1498, was known for religious reform, anti-[[Renaissance]] preaching, book burning, and destruction of what he considered immoral [[art]]. He vehemently preached against what he saw as the moral corruption of the clergy, and his main opponent was [[Pope Alexander]] VI. He is sometimes seen as a precursor of [[Martin Luther]] and the [[Protestant Reformation]], though he remained a devout and pious [[Roman Catholic]] during his whole life. | |

| − | + | The Order found itself face to face with the [[Renaissance]]. It struggled against what it believed were the pagan tendencies in [[humanism]], but it also furnished humanism with such advanced writers as [[Francesco Colonna]] and [[Matteo Bandello]]. Its members, in great numbers, took part in the artistic activity of the age, the most prominent being [[Fra Angelico]] and [[Fra Bartolomeo]]. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ====The Inquisition==== |

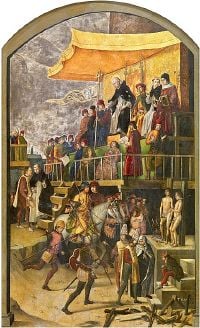

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Pedro Berruguete - Saint Dominic Presiding over an Auto-da-fe (1475).jpg|thumb|200px|Saint Dominic presiding at an inquisition. Although the painting is anachronistic, the Dominicans indeed played a leading role in the Inquisition.]] |

| + | The Dominican Order was instrumental in the [[Inquisition]]. In the twelfth century, to counter the spread of [[Catharism]], prosecution against [[heresy]] became more frequent. As the Dominicans were particularly trained in the necessary skills to identify heretics and deal with them, in the thirteenth century, the [[Pope]] assigned the duty of carrying out inquisitions to the Dominican Order. Dominican inquisitors acted in the name of the Pope and with his full authority. The inquisitor questioned the accused heretic in the presence of at least two witnesses. The accused was given a summary of the charges and had to take an oath to tell the truth. Various means were used to get the cooperation of the accused. Although there was no tradition of [[torture]] in Christian [[canon law]], this method came into use by the middle of the thirteenth century. | ||

| − | The | + | The findings of the Inquisition were read before a large audience; the penitents abjured on their knees with one hand on a [[bible]] held by the inquisitor. Penalties went from visits to churches, [[pilgrimages]], and wearing the cross of infamy to imprisonment (usually for life but the sentences were often commuted) and (if the accused would not abjure) [[death]]. Death was by burning at the stake, and was carried out by the secular authorities. In some serious cases when the accused had died before proceedings could be instituted, his or her remains could be exhumed and burned. Death or [[life imprisonment]] was always accompanied by the confiscation of all the property of the accused. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Dominicans were sent as inquisitors in 1232 to [[Germany]] along the [[Rhine]], to the Diocese of Tarragona in [[Spain]] and to [[Lombardy]]; in 1233 to [[France]], to the territory of Auxerre; the ecclesiastical provinces of [[Bourges]], [[Bordeaux]], [[Narbonne]], and [[Auch]], and to [[Burgundy]]; in 1235 to the ecclesiastical province of [[Sens]]. By 1255, the Inquisition was in full activity in all the countries of Central and Western [[Europe]]—in the county of [[Toulouse]], in [[Sicily]], [[Aragon]], Lombardy, France, Burgundy, [[Brabant]], and Germany. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | The | + | The fifteenth century witnessed Dominican involvement in the [[Spanish Inquisition]]. [[Alonso de Hojeda]], a Dominican from [[Seville]], convinced [[Queen Isabella]] of the existence of [[Crypto-Judaism]] among Andalusian ''conversos'' during her stay in Seville between 1477 and 1478. A report, produced at the request of the monarchs by [[Pedro González de Mendoza]], Archbishop of Seville and by the Segovian Dominican [[Tomás de Torquemada]], corroborated this assertion. The [[monarchs]] decided to introduce the Inquisition to [[Castile]] to uncover and do away with false [[converts]]. The Spanish Inquisition brought the deaths of many Jews found to be insincere in their conversions and resulted in the expulsion of the Jewish from Spain in 1492. |

| − | + | In 1542, [[Pope Paul III]] established a permanent [[congregation]] staffed with cardinals and other officials whose task it was to maintain and defend the integrity of the faith and to examine and proscribe errors and false doctrines. This body, the [[Congregation of the Holy Office]] (now called the [[Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith]]), became the supervisory body of local inquisitions. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | ====Dominicans versus Franciscans==== | |

| + | In the [[Middle Ages]], theological debates took place at the [[University of Paris]] between the Aristotelian Dominicans and the Franciscan Platonists. Many of these encounters lacked what could be called [[Christian]] love in their search for truth. The Franciscans made themselves felt alongside of the Dominicans, and created a rival school of [[theology]] as contrasted with the [[Aristotelianism]] of the Dominican school. | ||

| − | + | As a result, the Paris theology [[faculty]] protested the use of Aristotle's natural philosophy (but not his logic) in the arts preparatory courses, and succeeded in having it banned in 1210. [[Thomas Aquinas]] was one of the Dominicans who articulately defended Greek learning against the objections of the Franciscans. By 1255, however, Aristotle won the day it became apparent that [[students]] would start going elsewhere to study Aristotle if they could not get it in Paris. | |

| − | + | In the Franciscan versus Dominican rivalry, pointed differences also occurred on the [[Mendicant Orders]]: the Dominicans adopted the existing [[monastic rule]], while the Franciscans did not allow personal [[property]]. After the death of the founders, [[St. Dominic]] and [[St. Francis]], re-discussions and reinterpretations of the notion of [[poverty]] continued. The quarrel continued for some 70 years and was at times extremely bitter. | |

| − | + | ===Modern Period=== | |

| + | [[Image:Bartolomedelascasas.jpg|thumb|200px|right|[[Bartolomé de Las Casas]] became famous for his advocacy of the rights of Native Americans, whose cultures, especially in the [[Caribbean]], he describes with care.]] | ||

| − | + | At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the progress of the [[Protestant]] "heresy" in Europe and Britain cost the Order six or seven provinces and several hundreds of [[convent]]s. [[Queen Mary I]] of [[England]] (r. 1553-1558) used the Dominicans in her effort to reverse the [[Protestant Reformation]], an effort which proved futile. | |

| − | + | In spite of these setbacks, the discovery of the [[New World]] opened up a fresh field of missionary activity. One of the most famous Dominicans of this period was [[Bartolomé de Las Casas]], who argued forcefully for the rights of Native Americans in the Caribbean. The order's gains in [[Americas|America]], the [[Indies]] and [[Africa]] during the period of colonial expansion far exceeded the losses of the order in Europe, and the [[seventeenth century]] saw its highest numerical development. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In modern times, the order lost much of its influence on the political powers, which had universally fallen into [[absolutism]] and had little sympathy for the [[democratic]] constitution of the Preachers. The [[House of Bourbon|Bourbon]] courts of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were particularly unfavorable to them until the suppression of the [[Society of Jesus]] (the Jesuits). In the eighteenth century, there were numerous attempts at reform which created, especially in France, geographical confusion in the administration. Also during the eighteenth century, the tyrannical spirit of the European powers and the spirit of the age lessened the number of recruits and the fervor of religious life. The [[French Revolution]] ruined the order in France, and the crises which more or less rapidly followed considerably lessened or wholly destroyed numerous provinces. | |

| − | In | + | ===Recent period=== |

| + | In the beginning of the nineteenth century the number of Preachers reached a low of around 3,500. The French restoration, however, furnished many Preachers to other provinces, to assist in their organization and progress. From it came Père [[Vincent Jandel]] (1850-1872), who remained the longest-serving [[master general]] of the nineteenth century. The province of St. Joseph in the United States was founded in 1805 by Father [[Edward Fenwick]], the first Bishop of [[Cincinnati, Ohio]] (1821-1832). Afterwards, this province developed slowly, but now ranks among the most flourishing and active provinces of the Order. | ||

| − | + | In 1910, the Order had 20 archbishops or bishops, and a total of 4,472 both nominally and actually engaged in the activities of the Order. Since that year, the Order has published an important review in [[Madrid]], ''La Ciencia Tomista.'' | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | [[Image:San Domenico11.jpg|thumb|right|225px|Dominican in habit]] | |

| − | + | French Dominicans founded and ran the French Biblical and Archæological School of Jerusalem, one of the leading international centers for Biblical research of all kinds. It was here that the famed [[Jerusalem Bible]] (both editions) was prepared. Likewise, [[Yves Congar|Yves Cardinal Congar]], O.P., one of the emblematic theologians of the twentieth century, was a product of the French province of the Order of Preachers. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1992, the followers of St. Dominic from 90 countries sent representatives to the General Chapter of 1992 in [[Mexico]]. They were engaged in every imaginable work, from running an ecological farm in [[Benin]] to exploring Coptic verbs in [[Fribourg]], [[Germany]]. Recent General Chapters have tried to help the Order focus its priorities in face of such endless demands and possibilities. In particular, the apostolic commitment aims to achieve four main objectives: intellectual formation, world [[mission]], social [[communication]], and [[justice]]. | |

| − | + | Over the past 20 years, there has been a decline in the number of Preachers throughout the Dominican Order that has been most severely experienced in its emerging churches. Provinces which once sent large numbers of Preachers to evangelize in other countries are no longer able to do so. "This has led to an acute shortage of key personnel in a number of [[mission]] vicariates and provinces," notes the Order website, <ref>[http://www.op.org/international/english/index.html Dominican Order website], ''www.op.org''. Retrieved October 24, 2007.</ref> which adds that, “In certain cases the addition of just two or three would alleviate a critical situation.” | |

| − | : | + | ==The four ideals of the Dominican spirit and heritage== |

| + | The Dominican heritage intertwines a dynamic interrelatedness of four active [[ideals]]: | ||

| − | + | '''Study:''' Dominican [[tradition]] and [[heritage]] of study is [[freedom]] of [[research]]. Dominic set [[study]] in the service of others as his ideal when he made study an integral part of the life of the Order. Study and concern was focused on contemporary social issues, so that one would go from study of the world as it is to a commitment to envision and work for a world as it should be; to try to put right what is wrong in the world. Each person has to determine her/his own area of commitment, and then establish the desire and challenge to make this a better world. Dominic believed that you learn how to do something by doing it, not by formulating [[theories]] beforehand. Experience was the key. | |

| − | : | + | '''Prayer/Contemplation/Reflection:''' For example, love of the [[Gospel of Matthew]]. |

| − | + | '''Community:''' To work for a better, more just and loving world. If we try to do this alone, we can feel overwhelmed. We can help one another—that is the point of [[community]] and [[family]], to enable us to do what we cannot do by ourselves. | |

| − | '' | ||

| − | + | '''Service:''' Compassion was one of Dominic’s outstanding qualities. For example, as a student in Palencia he said, “I refuse to study dead skins while men are dying of hunger.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | These ideals developed as the Order developed under Saint Dominic and his successors. Dominic differed from founders of other religious orders of his time in that he sent his followers to engage in the life of the emerging [[universities]] of the thirteenth century. While they studied, they realized that there must be a spirit of [[prayer]], [[contemplation]], and [[reflection]] that would connect the world of ideas, the life of the mind, and the spirit of [[truth]], to the reality of the goodness of the Creator. This reflection and prayer could not be done in a vacuum, but must be done in and through the sharing of [[communal life]]. Coming full circle, the Dominicans were commissioned to share their knowledge and love of God with the people of the world. Thus, the Order of Preachers continues to share the [[Good News]] of the Gospel through the [[service]] and [[ministry]] they perform. | |

| − | + | ===Mottos=== | |

| + | 1. ''Laudare, Benedicere, Praedicare'' | ||

| + | :To praise, to bless and to preach | ||

| − | + | 2. ''Veritas'' | |

| − | '' | + | :Truth |

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | 3. ''Contemplare et Contemplata Aliis Tradere'' | |

| − | + | :To study (or contemplate) and to hand on the fruits of study | |

| − | As well as the friars, Dominican sisters , also known as the Order of Preachers, live their lives supported by four common values, often referred to as the Four Pillars of Dominican Life, they are: community life, common prayer, study and service. St. Dominic called this fourfold pattern of life the "holy preaching." Henri Matisse was so moved by the care that he received from the Dominican Sisters that he collaborated in the design and interior decoration of their [[Chapelle du Saint-Marie du Rosaire]] in [[Vence]], [[France]]. | + | ===Dominican Sisters=== |

| + | As well as the friars, Dominican sisters, also known as the Order of Preachers, live their lives supported by four common values, often referred to as the Four Pillars of Dominican Life, they are: community life, common prayer, study and service. St. Dominic called this fourfold pattern of life the "holy preaching." Henri Matisse was so moved by the care that he received from the Dominican Sisters that he collaborated in the design and interior decoration of their [[Chapelle du Saint-Marie du Rosaire]] in [[Vence]], [[France]]. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Important Dominicans== |

| − | + | Important Dominicans include: [[Saint Dominic]], St. [[Thomas Aquinas]], [[Albertus Magnus]], St. [[Catherine of Siena]], St. [[Raymond of Peñafort]], St. [[Rose of Lima]], St. [[Martin de Porres]], [[Pope Pius V|Pope Saint Pius V]], Beato [[Jordan of Saxony]], [[Bartolomé de las Casas]], [[Tomás de Torquemada]], and [[Girolamo Savonarola]]. | |

| − | + | Four Dominican [[Cardinal (Catholicism)|cardinal]]s have reached the Papacy: [[Pope Innocent V|Innocent V]], [[Pope Benedict XI|Benedict XI]], [[Pius V]], and [[Pope Benedict XIII|Benedict XIII]]. Currently, in the [[College of Cardinals]] there are two Dominican cardinals: [[Christoph Cardinal Schönborn]], Archbishop of [[Wien|Vienna]]; and [[Georges Marie Martin Cardinal Cottier]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | * Alemany, J.S. ''The Life of St. Dominic and a Sketch of the Dominican Order''. Kessinger Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0548105597 |

| − | * | + | * Hinnebusch, William A. ''The History of the Dominican Order''. Alba House, 1966. ISBN 9780818902666 |

| − | + | * Tugwell, Simon. ''Early Dominicans: Selected Writings''. Paulist Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0809124145 | |

| − | * | + | * Zagano, Phyllis, and Thomas McGonigle. ''The Dominican Tradition''. Liturgical Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0814619117 |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 30, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ===Dominican-founded schools === | + | * [http://www.op.org/ Order of Preachers] - Available in English, French and Spanish. ''www.op.org''. |

| − | * [http://www.aquinas.edu/ Aquinas College, Grand Rapids, MI] | + | * [http://domlife.org/ Dominican Life USA online news magazine] – ''domlife.org''. |

| + | |||

| + | ===Dominican-founded schools=== | ||

| + | * [http://www.aquinas.edu/ Aquinas College, Grand Rapids, MI]. | ||

* [http://www.ai.edu/ Aquinas Institute of Theology, St. Louis, MO] | * [http://www.ai.edu/ Aquinas Institute of Theology, St. Louis, MO] | ||

* [http://www.barry.edu/ Barry University of Miami, FL] | * [http://www.barry.edu/ Barry University of Miami, FL] | ||

* [http://www.dom.edu/ Dominican University, River Forest, IL] | * [http://www.dom.edu/ Dominican University, River Forest, IL] | ||

| − | |||

* [http://www.dhs.edu/ Dominican House of Studies, Washington, DC] | * [http://www.dhs.edu/ Dominican House of Studies, Washington, DC] | ||

* [http://www.dspt.edu/ Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology, Berkeley, CA] | * [http://www.dspt.edu/ Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology, Berkeley, CA] | ||

| − | |||

* [http://www.jordandesajonia.edu.co/ Jordán de Sajonia School, Bogotá, Colombia] | * [http://www.jordandesajonia.edu.co/ Jordán de Sajonia School, Bogotá, Colombia] | ||

| − | |||

* [http://www.providence.edu/ Providence College, Providence RI] | * [http://www.providence.edu/ Providence College, Providence RI] | ||

| − | + | * [http://www.ust.edu.ph/ University of Santo Tomas. Manila, Philippines] | |

| − | * [http://www.ust.edu.ph/ | + | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

{{Credit|154015226}} | {{Credit|154015226}} | ||

Latest revision as of 17:16, 30 January 2024

The Dominican Order, originally known as the Order of Preachers, is a Catholic religious order created by Saint Dominic in the early thirteenth century in France. Dominic established his religious community in Toulouse in 1214, officially recognized as an order by Pope Honorius III in 1216. Founded under the Augustinian rule, the Dominican Order is one of the great orders of mendicant friars that revolutionized religious life in Europe during the High Middle Ages. However, it notably differed from the Franciscan Order in its attitude toward ecclesiastical poverty.

Established to preach the Gospel and to combat heresy, the order is famed for its intellectual tradition, having produced many leading theologians and philosophers. It played a leading role in investigating and prosecuting heresy during the Inquisition. Important Dominicans include Saint Dominic, St. Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, St. Catherine of Siena, and Girolamo Savonarola. Four Dominican cardinals have become popes.

In England and some other countries the Dominicans are referred to as Blackfriars on account of the black cappa or cloak they wear over their white habits. In France, the Dominicans are also known as Jacobins, because their first convent in Paris bore the name "Saint Jacques," or Jacobus in Latin. They have also been referred to using a Latin pun, as "Domini canes," or "The Hounds of God," a reference to the order's reputation as most obedient servants of the faith, sometimes with a negative connotation or reference to the order's involvement with the Inquisition.

The Dominican Order is headed by the Master of the Order, who is currently Brother Carlos Azpiroz Costa. Members of the order often carry the letters O.P. after their name.

Foundation of the Order

Dominic saw the need to establish a new kind of order when traveling through the south of France when that region was the stronghold of heretical Albigensian thought—also known as Catharism—centered around the town of Albi.[1] To combat heresy and other problems in urban areas, he sought to establish an order that would bring the systematic education of the older monastic orders such as the Benedictines to bear on the religious problems of the burgeoning population of cities. His was to be a preaching order, trained to preach in the vernacular languages, but with a sound background in academic theology. Rather than earning their living on vast farms as the monasteries had done, the new friars would survive by persuasive preaching and the alms-giving of those who heard them. They were initially scorned by more traditional orders, who thought these "urban monks" would never survive the temptations of the city.

The Dominicans were thus set up as the branch of the Catholocism Church to deal with heresy. The organization of the Order of Preachers was approved in December 1216 by Pope Honorius III.

History of the Order

Middle Ages

The thirteenth century is the classic age of the order. It reached all classes of Christian society fighting heresy, schism, and paganism. Its schools spread throughout the entire Church. Its doctors wrote monumental works in all branches of knowledge and two among them, Albertus Magnus, and especially Thomas Aquinas, founded a school of philosophy and theology which was to rule the ages to come in the life of the Church.

An enormous number of its members held offices in both Church and state—as popes, cardinals, bishops, legates, inquisitors, confessors of princes, ambassadors, and paciarii (enforcers of the peace decreed by popes or councils). A period of relaxation ensued during the fourteenth century owing to the general decline of Christian society. The weakening of doctrinal activity favored the development of the ascetic and contemplative life sprang up, especially in Germany and Italy, an intense and exuberant mysticism with which the names of Meister Eckhart, Heinrich Suso, Johannes Tauler, and St. Catherine of Siena are associated, which has also been called "Dominican mysticism." This movement was the prelude to the reforms undertaken at the end of the century, by Raymond of Capua, and continued in the following century. It assumed remarkable proportions in the congregations of Lombardy and the Netherlands, and in the reforms of Girolamo Savonarola at Florence.

Savonarola, an Italian Dominican priest and leader of Florence from 1494 until his execution in 1498, was known for religious reform, anti-Renaissance preaching, book burning, and destruction of what he considered immoral art. He vehemently preached against what he saw as the moral corruption of the clergy, and his main opponent was Pope Alexander VI. He is sometimes seen as a precursor of Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation, though he remained a devout and pious Roman Catholic during his whole life.

The Order found itself face to face with the Renaissance. It struggled against what it believed were the pagan tendencies in humanism, but it also furnished humanism with such advanced writers as Francesco Colonna and Matteo Bandello. Its members, in great numbers, took part in the artistic activity of the age, the most prominent being Fra Angelico and Fra Bartolomeo.

The Inquisition

The Dominican Order was instrumental in the Inquisition. In the twelfth century, to counter the spread of Catharism, prosecution against heresy became more frequent. As the Dominicans were particularly trained in the necessary skills to identify heretics and deal with them, in the thirteenth century, the Pope assigned the duty of carrying out inquisitions to the Dominican Order. Dominican inquisitors acted in the name of the Pope and with his full authority. The inquisitor questioned the accused heretic in the presence of at least two witnesses. The accused was given a summary of the charges and had to take an oath to tell the truth. Various means were used to get the cooperation of the accused. Although there was no tradition of torture in Christian canon law, this method came into use by the middle of the thirteenth century.

The findings of the Inquisition were read before a large audience; the penitents abjured on their knees with one hand on a bible held by the inquisitor. Penalties went from visits to churches, pilgrimages, and wearing the cross of infamy to imprisonment (usually for life but the sentences were often commuted) and (if the accused would not abjure) death. Death was by burning at the stake, and was carried out by the secular authorities. In some serious cases when the accused had died before proceedings could be instituted, his or her remains could be exhumed and burned. Death or life imprisonment was always accompanied by the confiscation of all the property of the accused.

The Dominicans were sent as inquisitors in 1232 to Germany along the Rhine, to the Diocese of Tarragona in Spain and to Lombardy; in 1233 to France, to the territory of Auxerre; the ecclesiastical provinces of Bourges, Bordeaux, Narbonne, and Auch, and to Burgundy; in 1235 to the ecclesiastical province of Sens. By 1255, the Inquisition was in full activity in all the countries of Central and Western Europe—in the county of Toulouse, in Sicily, Aragon, Lombardy, France, Burgundy, Brabant, and Germany.

The fifteenth century witnessed Dominican involvement in the Spanish Inquisition. Alonso de Hojeda, a Dominican from Seville, convinced Queen Isabella of the existence of Crypto-Judaism among Andalusian conversos during her stay in Seville between 1477 and 1478. A report, produced at the request of the monarchs by Pedro González de Mendoza, Archbishop of Seville and by the Segovian Dominican Tomás de Torquemada, corroborated this assertion. The monarchs decided to introduce the Inquisition to Castile to uncover and do away with false converts. The Spanish Inquisition brought the deaths of many Jews found to be insincere in their conversions and resulted in the expulsion of the Jewish from Spain in 1492.

In 1542, Pope Paul III established a permanent congregation staffed with cardinals and other officials whose task it was to maintain and defend the integrity of the faith and to examine and proscribe errors and false doctrines. This body, the Congregation of the Holy Office (now called the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith), became the supervisory body of local inquisitions.

Dominicans versus Franciscans

In the Middle Ages, theological debates took place at the University of Paris between the Aristotelian Dominicans and the Franciscan Platonists. Many of these encounters lacked what could be called Christian love in their search for truth. The Franciscans made themselves felt alongside of the Dominicans, and created a rival school of theology as contrasted with the Aristotelianism of the Dominican school.

As a result, the Paris theology faculty protested the use of Aristotle's natural philosophy (but not his logic) in the arts preparatory courses, and succeeded in having it banned in 1210. Thomas Aquinas was one of the Dominicans who articulately defended Greek learning against the objections of the Franciscans. By 1255, however, Aristotle won the day it became apparent that students would start going elsewhere to study Aristotle if they could not get it in Paris.

In the Franciscan versus Dominican rivalry, pointed differences also occurred on the Mendicant Orders: the Dominicans adopted the existing monastic rule, while the Franciscans did not allow personal property. After the death of the founders, St. Dominic and St. Francis, re-discussions and reinterpretations of the notion of poverty continued. The quarrel continued for some 70 years and was at times extremely bitter.

Modern Period

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the progress of the Protestant "heresy" in Europe and Britain cost the Order six or seven provinces and several hundreds of convents. Queen Mary I of England (r. 1553-1558) used the Dominicans in her effort to reverse the Protestant Reformation, an effort which proved futile.

In spite of these setbacks, the discovery of the New World opened up a fresh field of missionary activity. One of the most famous Dominicans of this period was Bartolomé de Las Casas, who argued forcefully for the rights of Native Americans in the Caribbean. The order's gains in America, the Indies and Africa during the period of colonial expansion far exceeded the losses of the order in Europe, and the seventeenth century saw its highest numerical development.

In modern times, the order lost much of its influence on the political powers, which had universally fallen into absolutism and had little sympathy for the democratic constitution of the Preachers. The Bourbon courts of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were particularly unfavorable to them until the suppression of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits). In the eighteenth century, there were numerous attempts at reform which created, especially in France, geographical confusion in the administration. Also during the eighteenth century, the tyrannical spirit of the European powers and the spirit of the age lessened the number of recruits and the fervor of religious life. The French Revolution ruined the order in France, and the crises which more or less rapidly followed considerably lessened or wholly destroyed numerous provinces.

Recent period

In the beginning of the nineteenth century the number of Preachers reached a low of around 3,500. The French restoration, however, furnished many Preachers to other provinces, to assist in their organization and progress. From it came Père Vincent Jandel (1850-1872), who remained the longest-serving master general of the nineteenth century. The province of St. Joseph in the United States was founded in 1805 by Father Edward Fenwick, the first Bishop of Cincinnati, Ohio (1821-1832). Afterwards, this province developed slowly, but now ranks among the most flourishing and active provinces of the Order.

In 1910, the Order had 20 archbishops or bishops, and a total of 4,472 both nominally and actually engaged in the activities of the Order. Since that year, the Order has published an important review in Madrid, La Ciencia Tomista.

French Dominicans founded and ran the French Biblical and Archæological School of Jerusalem, one of the leading international centers for Biblical research of all kinds. It was here that the famed Jerusalem Bible (both editions) was prepared. Likewise, Yves Cardinal Congar, O.P., one of the emblematic theologians of the twentieth century, was a product of the French province of the Order of Preachers.

In 1992, the followers of St. Dominic from 90 countries sent representatives to the General Chapter of 1992 in Mexico. They were engaged in every imaginable work, from running an ecological farm in Benin to exploring Coptic verbs in Fribourg, Germany. Recent General Chapters have tried to help the Order focus its priorities in face of such endless demands and possibilities. In particular, the apostolic commitment aims to achieve four main objectives: intellectual formation, world mission, social communication, and justice.

Over the past 20 years, there has been a decline in the number of Preachers throughout the Dominican Order that has been most severely experienced in its emerging churches. Provinces which once sent large numbers of Preachers to evangelize in other countries are no longer able to do so. "This has led to an acute shortage of key personnel in a number of mission vicariates and provinces," notes the Order website, [2] which adds that, “In certain cases the addition of just two or three would alleviate a critical situation.”

The four ideals of the Dominican spirit and heritage

The Dominican heritage intertwines a dynamic interrelatedness of four active ideals:

Study: Dominican tradition and heritage of study is freedom of research. Dominic set study in the service of others as his ideal when he made study an integral part of the life of the Order. Study and concern was focused on contemporary social issues, so that one would go from study of the world as it is to a commitment to envision and work for a world as it should be; to try to put right what is wrong in the world. Each person has to determine her/his own area of commitment, and then establish the desire and challenge to make this a better world. Dominic believed that you learn how to do something by doing it, not by formulating theories beforehand. Experience was the key.

Prayer/Contemplation/Reflection: For example, love of the Gospel of Matthew.

Community: To work for a better, more just and loving world. If we try to do this alone, we can feel overwhelmed. We can help one another—that is the point of community and family, to enable us to do what we cannot do by ourselves.

Service: Compassion was one of Dominic’s outstanding qualities. For example, as a student in Palencia he said, “I refuse to study dead skins while men are dying of hunger.”

These ideals developed as the Order developed under Saint Dominic and his successors. Dominic differed from founders of other religious orders of his time in that he sent his followers to engage in the life of the emerging universities of the thirteenth century. While they studied, they realized that there must be a spirit of prayer, contemplation, and reflection that would connect the world of ideas, the life of the mind, and the spirit of truth, to the reality of the goodness of the Creator. This reflection and prayer could not be done in a vacuum, but must be done in and through the sharing of communal life. Coming full circle, the Dominicans were commissioned to share their knowledge and love of God with the people of the world. Thus, the Order of Preachers continues to share the Good News of the Gospel through the service and ministry they perform.

Mottos

1. Laudare, Benedicere, Praedicare

- To praise, to bless and to preach

2. Veritas

- Truth

3. Contemplare et Contemplata Aliis Tradere

- To study (or contemplate) and to hand on the fruits of study

Dominican Sisters

As well as the friars, Dominican sisters, also known as the Order of Preachers, live their lives supported by four common values, often referred to as the Four Pillars of Dominican Life, they are: community life, common prayer, study and service. St. Dominic called this fourfold pattern of life the "holy preaching." Henri Matisse was so moved by the care that he received from the Dominican Sisters that he collaborated in the design and interior decoration of their Chapelle du Saint-Marie du Rosaire in Vence, France.

Important Dominicans

Important Dominicans include: Saint Dominic, St. Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, St. Catherine of Siena, St. Raymond of Peñafort, St. Rose of Lima, St. Martin de Porres, Pope Saint Pius V, Beato Jordan of Saxony, Bartolomé de las Casas, Tomás de Torquemada, and Girolamo Savonarola.

Four Dominican cardinals have reached the Papacy: Innocent V, Benedict XI, Pius V, and Benedict XIII. Currently, in the College of Cardinals there are two Dominican cardinals: Christoph Cardinal Schönborn, Archbishop of Vienna; and Georges Marie Martin Cardinal Cottier.

Notes

- ↑ Catharism was a name given to a religious sect with gnostic elements that appeared in the Languedoc region of France in the eleventh century and flourished in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Catharism had its roots in the Paulician movement in Armenia and was also influenced by the Bogomiles with whom the Paulicians eventually merged. They also became influenced by dualist and perhaps Manichaean beliefs.

- ↑ Dominican Order website, www.op.org. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alemany, J.S. The Life of St. Dominic and a Sketch of the Dominican Order. Kessinger Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0548105597

- Hinnebusch, William A. The History of the Dominican Order. Alba House, 1966. ISBN 9780818902666

- Tugwell, Simon. Early Dominicans: Selected Writings. Paulist Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0809124145

- Zagano, Phyllis, and Thomas McGonigle. The Dominican Tradition. Liturgical Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0814619117

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2024.

- Order of Preachers - Available in English, French and Spanish. www.op.org.

- Dominican Life USA online news magazine – domlife.org.

Dominican-founded schools

- Aquinas College, Grand Rapids, MI.

- Aquinas Institute of Theology, St. Louis, MO

- Barry University of Miami, FL

- Dominican University, River Forest, IL

- Dominican House of Studies, Washington, DC

- Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology, Berkeley, CA

- Jordán de Sajonia School, Bogotá, Colombia

- Providence College, Providence RI

- University of Santo Tomas. Manila, Philippines

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.