Dao

| 60px |

| Composition 1: 道 (dào) is 首 (shǒu) 'head' and 辶 (辵 chuò) 'go' (Source: Wenlin) |

| Pinyin: Dào |

| Wade-Giles: Tao |

| Japanese: Dō, (tō), michi |

| Korean: 도 (To) |

| Vietnamese: Đạo |

Tao or Dao (道, Pinyin: Dào, Cantonese: Dou) is a Chinese character often translated as ‘Way’ or 'Path'. Though often seen as a linguistic monad (especially by Westerners), the character dao was often modified by other nouns, each of which represented a subset of the terms multifarious meanings. Three such compounds gained special currency in classical Chinese philosophy: 天道 Tian dao (sky or natural dao—usually translated religiously as "heaven's Dao") 大道 Da Dao (Great dao—the actual course of all history—everything that has happened or will happen) and 人道 Ren dao (human dao, the normative orders constructed by human (social) practices). The natural dao corresponds roughly to the order expressed in the totality of natural (physical) laws. The relationship between these three was one of the central subjects of the discourses of Laozi, Zhuangzi, and many other Chinese philosophers.

From the earliest recorded religio-philosophical texts onward, Tian Dao is explained using the concepts of yin and yang. The resulting cosmology became a distinctive feature of Chinese philosophy, one which was particularly expounded upon by members of the Daoist school. The early thinkers, Laozi and Zhuangzi, expressed the view that human dao was embedded in natural dao. If human lives are lived in accord with the natural order of reality, then human beings can truly fulfill their innate potentialities.

Etymology

The composition of 道 (dào) is 首 (shǒu) meaning "head" and 辶 (辵 chuò) "go." The decomposition etymology for the character 首 is distinguished by the tufts at the top, representing the distinctive hairstyle of the warrior class (a "bun"). The character 首 itself is used to refer to concepts related to the head, such as leadership and rulership. The character 辶 (辵 chuò) 'go' in its reduced form, 廴 resembles a foot, and is meant to be evocative of its meaning "to walk," and "to go," as well as the generic radix for "the way of." This reduced radical 廴 is a component in other radicals and characters. As such, the combined characters signify directed, forward movement (and perhaps even "process" in a Whiteheadian sense).[1]

Dao in an Early Chinese Context

- See: Confucius, Confucianism

Though the concept of Dao is most often understood in light of its Daoist exponents, the term was actually an important element of Chinese religio-philosophical discourse since time immemorial. However, these thinkers almost exclusively utilized in the human context (ren dao (人道)) rather than the cosmological notion that came to dominate later usage. The clearest example of this early understanding can be seen in the Analects of Confucius.

In this formative text, the Master Kong uses dao to describe the optimal, praxis-based path for individual aspirants and the verbal act of following that path (a distinction that relies on the grammatical ambiguity of classical Chinese). This path is open to all people, but is dependent upon heartfelt study of the Five Classics and internalization of the rules of ritual propriety (li). As described in Ames and Rosemont's masterful introduction to the Analects, "to realize the dao is to experience, to interpret, and to influence the world in such a way as to reinforce and extend the way of life inherited from one's cultural predecessors. This way of living in the world then provides a road map and direction for one's cultural successors."[2] Inherent in this notion is the view that following (or embodying) the dao is a difficult process requiring constant study and effort:

- Ranyou said, "It is not that I do not rejoice in the way (dao) of the Master, but that I do not have the strength to walk it."

- The Master said, "Those who do not have the strength for it collapse somewhere along the way. But with you, you have drawn your own line before you start" (6.12).

Another distinctive element of the Confucian Dao is that it is particularistic: different disciples are given specific instruction based upon their innate qualities and characteristics:

- Gongxi Hua said, "When Zilu asked the question, you observed that his father and elder brothers are still alive, but when Ranyou asked the same question, you told him to act on what he learns. I am confused—could you explain this to me?"

- The Master replied, "Ranyou is diffident, and so I urged him on. But Zilu has the energy of two, and so I sought to rein him in" (11.22).

In this way, while the dao is interpreted as a single path (that one is either walking or has strayed from), it is still adapted to each individual's aptitudes. In this context, harmonious behavior results from the optimizing one's tendencies and attitudes through the emulation of classical models: a moral vision that is most clearly described in the Zhong Yong (Doctrine of the Mean).

A. C. Graham's Disputers of the Tao elegantly summarizes the Confucian dao: "the Way is mentioned explicitly only as the proper course of human conduct and government. Indeed he think of it as itself widened by the broadening of human culture: 'Man is able to enlarge the Way [dao], it is not that the Way enlarges man' (15.29)."[3] This humanistic understanding was prevalent in the pre-Daoist period.

This being said, the fact that most key terms (i.e. dao, de, tian, wu-wei) were shared throughout the religious and philosophical corpora meant that later developments and modifications had considerable significance, even outside their tradition of origin. For instance, Neo-Confucian thought expanded the classical understanding of dao by including Daoist-inspired cosmological notions (as discussed below).

Dao in the Daoist Context

- See also: Laozi, Dao De Jing, Zhuangzi, wu-wei, Liezi

Unlike other early Chinese thinkers, the philosophers who came to be retroactively identified as Daoists stressed the self-ordering simplicity of the natural world as a logical corrective for the problems plaguing human life. This naturalistic connection was commented on at length by both Laozi and Zhuangzi, as well as later philosophers such as Liezi, Ge Hong and Wang Bi.

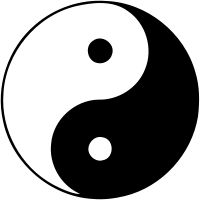

The concept of Dao is based upon the understanding that the only constant in the universe is change (see I Jing, the "Book of Changes") and that we must understand and attempt to harmonize ourselves with this change. Change is characterized as a constant progression from non-being into being, potential into actual, yin into yang, female into male. This understanding is first suggested in the Yi Jing, which states that "one (phase of) Yin, one (phase of) Yang, is what is called the Dao." Being thus placed at the conjunction of the alternation of yin and yang, the Dao can be understood as the continuity principle that underlies the constant evolution of the world. For this reason, the Dao is often symbolized by the Taijitu (yin-yang), which represents the yin (darkness) and yang (brightness) mutually generating and interpenetrating in an endless cycle.

The Dao is the main theme discussed in the Dao De Jing, an ancient Chinese scripture attributed to Laozi. This book does not specifically define what the Dao is; it affirms that in the first sentence, "The Dao that can be told of is not an Unvarying Dao" (tr. Waley, modified). Instead, it points to some characteristics of what could be understood as being the Dao. Below are some excerpts from the book.

- All things arise from Dao. They are nourished by Virtue. They are formed from matter. They are shaped by environment. Thus the ten thousand things all respect Dao and honor Virtue. Respect of Dao and honor of Virtue are not demanded. But they are in the nature of things. Therefore all things arise from Dao. By Virtue they are nourished, developed, cared for, sheltered, comforted, grown and protected. Creating without claiming; doing without taking credit; guiding without interfering - this is Primal Virtue. (verse 51. tr. ibid )

- The great Dao flows everywhere, both to the left and to the right. The ten thousand things depend upon it; it holds nothing back. It fulfills its purpose silently and makes no claim. It nourishes the ten thousand things. And yet is not their lord. It has no aim; it is very small. The ten thousand things return to it, yet it is not their lord. It is very great. It does not show its greatness, And is therefore truly great. (verse 34. tr. ibid)

- Yield and overcome; bend and be straight; empty and be full; wear out and be new; have little and gain; have much and be confused. Therefore wise men embrace the one and set an example to all. Not putting on a display, they shine forth. Not justifying themselves, they are distinguished. Not boasting, they receive recognition. Not bragging, they never falter. They do not quarrel so no one quarrels with them. Therefore the ancients say, “Yield and overcome.” Is that an empty saying? Be really whole and all things will come to you. (verse 22. tr. Gia Fu Feng)

- Dao as the origin of things: "Dao begets one; One begets two; Two begets three; Three begets the myriad creatures." (TTC 42, tr. Lau, modified)

- Dao as an inexhaustible nothingness: "The Way is like an empty vessel / That yet may be drawn from / Without ever needing to be filled." (TTC 4, tr. Waley)

- Dao is omnipotent and infallible: "What Dao plants cannot be plucked, what Dao clasps, cannot slip." (TTC 54, tr. Waley)

A common theme in Daoist literature is that fulfilment in life cannot be attained by forcing one's own destiny; instead, one must be receptive to the path laid for them by nature and circumstance, which will themselves provide what is necessary. Laozi taught that the wisest approach was a way of ‘non-action’ ("wu-wei") – not inaction but rather a harmonization of one’s personal will with the natural harmony and justice of Nature. ‘The World is ruled by letting things take their natural course. It cannot be ruled by going against nature or arrogance.’ (Dao De Jing; Verse 48). It also means that the individual should do things natural to him and appropriate to do in his circumstances, thus serving as an instrument of the Law rather than doing the things as individuals. That is why no one should take any credit for things done. Nature is stabilized by order, and humans along with all other natural phenomena exist within nature. Attempting to force one's own path is arrogant, futile and self-destructive.

It should be noted that in Daoism the complementary part of "non-action" (wu-wei) is that nothing necessary is left undone ("wu bu wei"). Thus, Daoism should be viewed as advocating the harmonization of "passivity" and "activity/creativity" instead of just being passive. In other words through stillness and receptivity natural intuition guides us in knowing when to act and when not to act.

Laozi contrasts the Great Way of the Dao with the way of human beings:

- The Dao of heaven is to take from those who have too much and give to those who do not have enough. Man’s way is different. He takes from those who do not have enough to give to those who already have too much. (verse 77. Tr. Gia Fu Feng)

Laozi characterizes the Way of Man as one in which force is applied without the attainment of desired results:

- Whenever you advise a ruler in the way of Dao, counsel him not to use force to conquer the universe. For this would only cause resistance. Thorn bushes spring up wherever the army has passed. Lean years follow in the wake of war. Just do what needs to be done. Never take advantage of power…Force is followed by loss of strength. This is not the way of Dao. That which goes against the Dao comes to an early end. (verse 30. tr. Gia Fu Feng)

All mankind’s troubles on the Earth are caused by his having forgotten the Great Way. Remembering the Great Way is a spiritual awareness of one’s deep connection with the entirety of creation. This involves the adoption of a mode of ‘non-action’ that is not inaction but rather a harmonization of one’s personal will – otherwise tending towards egotism – with the natural harmony and justice of Dao.

- Dao abides in non-action yet nothing is left undone. If kings and lords observed this, the ten thousand things would develop naturally. If they still desired to act they would return to the simplicity of formless substance. Without form there is no desire. Without desire there is tranquility. And in this way all things would be at peace. (verse 37. tr. Gia Fu Feng)

- The greatest virtue is to follow Dao and Dao alone. The Dao is elusive and intangible. Oh, it is intangible and elusive, and yet within is image. Oh, it is elusive and intangible, and yet within is form. Oh, it is dim and dark, and yet within is essence. This essence is very real, and therein lies faith. From the very beginning til now its name has never been forgotten. Thus I perceive the creation. How do I know the ways of creation? Because of this. (verse 21. tr. Gia Fu Feng)

Dao in Later Thought

Today, scientists call the creative principle at work in the universe the ‘principle of self-organization’ from the observed fact that naturally occurring phenomena organize themselves into complex interdependent systems each system a ‘whole’ in itself.[4]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- The Analects of Confucius. Translated and with an introduction by Roger T. Ames and Henry Rosemont, Jr. New York: Ballantine Books, 1998. ISBN 0345434072.

- Capra, Fritjof. The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism. Boston: Shambhala, 2000. ISBN 1570625190.

- Chang, Dr. Stephen T. The Great Tao. Tao Publishing, imprint of Tao Longevity LLC. 1985. ISBN 0-942196-01-5.

- Graham, A.C. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1993. ISBN 0-8126-9087-7.

- Lao Tsu/Tao Te Ching. Translated by Gia-Fu Feng & Jane English. New York: Vintage Books, 1972. ISBN 0679776192.

- Lao Tzu; Lau, D.C. (translator); Sarah Allan (editor). Tao Te Ching: Translation of the Ma Wang Tui Manuscripts, Everyman's Library, 1994. ISBN 0679433163.

- Lao Tzu; Chuang Tzu; Legge, James (translator), The Sacred Books of China: The Texts of Taoism, Dover Publications, Inc., 1962.

- Quong, Rose Chinese Characters: Their Wit and Wisdom. With Illustrations by Dr. Kinn Wei Shaw. Ram Press, 1944.

- Wei Wu Wei, "Why Lazarus Laughed: The Essential Doctrine Zen-Advaita-Tantra". London: Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., 1960. ISBN 1591810116.

External links

All web sources accessed August 24, 2007

- [http://www.tao-te-king.org/index.html Dao De Jing translations (Dr.Hilmar KLAUS)

- alt.philosophy.taoism FAQ, original Taoism Internet FAQ

- Taoism Directory, directory of sites with content related to Taoism and Taoist issues.

- About the Tao, Taoism Texts, explanations, software, images and video

- Center for Daoist Studies, web-based resource for the study and practice of Daoism

- The Way and Its Power, English, French, and German translations of the Dao De Jing

- Taoism Info Philosophical Taoism

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ See Wenlin, 1997-2007; Ames and Rosemont, 45. See also: "Dao" at [zhongwen.com zhongwen.com], which lists the etymology as a combination of "movement" and "ahead."

- ↑ Ames and Rosemont, 45.

- ↑ Graham, 18. However, he also notes a single passage in the Analects that could presuppose a Daoist understanding of the cosmos (17.19), stating that it "implies a fundamental unity of Heaven and man. [As such,] it suggests that with the perfect ritualisation of life we would understand our place in community and cosmos without the need of words" (ibid).

- ↑ See Capra (2000).