Difference between revisions of "Codex" - New World Encyclopedia

(article ready) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (60 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

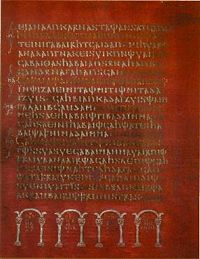

| − | {{ | + | [[Image:Codex Argenteus.jpg|thumb|200px|right|First page of the [[Codex Argenteus]]]] |

| + | A '''codex''' ([[Latin]] for ''block of wood,'' ''[[book]];'' plural ''codices'') is a book in the format used for modern books, with separate pages normally bound together and given a cover. Although the modern book is technically a codex, the term is used only for [[manuscripts]]. The codex was a Roman invention that replaced the [[scroll]], which was the first book form in all [[Eurasian]] cultures. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | While non-Christian traditions such as [[Judaism]] used scrolls, early [[Christianity|Christians]] used codices before it became popular. Christian scholars seemed to have used codices in order to distinguish their writings from Jewish scholarly works due to controversy and dispute particularly regarding the [[Old Testament]] and other [[theology|theological]] writings. By the fifth century, the codex became the primary writing medium for a general use. While the practical advantages of the codex format contributed to its increasing use, the rise of Christianity in the [[Roman Empire]] may have helped spread its popularity. | ||

| − | [[ | + | ==Overview== |

| − | + | Although technically any modern [[paperback]] is a codex, the term is used only for [[manuscript]] (hand-written) books, produced from [[Late Antiquity]] through the [[Middle Ages]]. The scholarly study of manuscripts from the point of view of the [[bookmaking]] craft is called [[codicology]]. The study of ancient documents in general is called [[paleography]]. | |

| − | + | Codicology (from [[Latin]] {{lang|la|''cōdex''}}, [[genitive]] {{lang|la|''cōdicis''}}, "notebook, book;" | |

| + | and [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] {{lang|grc|-λογία}}, ''[[-logy|-logia]]'') is the study of books as physical objects, especially [[manuscript]]s written on parchment in [[codex]] form. It is often referred to as 'the archaeology of the book', concerning itself with the materials ([[parchment]], sometimes referred to as membrane or [[vellum]], [[paper]], pigments, inks and so on), and techniques used to make books, including their binding. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Palaeography, palæography ([[British English|British]]), or '''paleography''' ([[American English|American]]) (from the [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] {{lang|grc|παλαιός}} ''palaiós,'' "old" and {{lang|grc|γράφειν}} ''graphein,'' "to write") is the study of ancient [[handwriting]], and the practice of deciphering and reading historical manuscripts.<ref>"Palaeography," ''Oxford English Dictionary.''</ref> |

| − | The codex was an improvement upon the scroll, which it gradually replaced, first in the West, and much later in Asia. | + | [[New World]] codices were written as late as the 16th century (see [[Maya codices]] and [[Aztec codices]]). Those written before the Spanish conquests seem all to have been single long sheets folded [[concertina]]-style, sometimes written on both sides of the local [[amatl]] paper. So, strictly speaking they are not in codex format, but they more consistently have "Codex" in their usual names than do other types of manuscript. |

| + | |||

| + | The codex was an improvement upon the [[scroll]], which it gradually replaced, first in the West, and much later in Asia. The codex in turn became the [[printing|printed]] [[book]], for which the term is not used. In [[China]], books were already printed but only on one side of the paper, and there were [[woodblock printing|intermediate]] stages, such as scrolls folded [[concertina]]-style and pasted together at the back.<ref>Colin Chinnery. [http://idp.bl.uk/education/bookbinding/bookbinding.a4d International Dunhuang Project--Several intermediate Chinese bookbinding forms from the C10th.] Retrieved October 8, 2008.</ref> | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

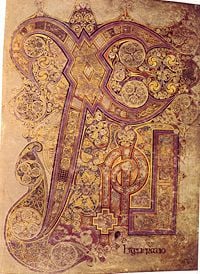

| − | The Romans used similar precursors made of reusable wax-covered tablets of wood for taking notes and other informal writings. The first recorded use of the codex for literary works dates from the late | + | [[Image:KellsFol034rChiRhoMonogram.jpg|right|200px|thumb|The [[Labarum|Chi Rho]] Monogram from the [[Book of Kells]]]] |

| + | [[Image:Codex Tro-Cortesianus.jpg|thumb|240px|Pages from Codex Tro-Cortesianus (Madrid) Maya Codex]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Florentine Codex IX Aztec Warriors.jpg||240px|thumb|left|Aztec warriors as shown in the [[Florentine Codex]].]] | ||

| + | The basic form of the codex was invented in [[Pergamon]] in the third century B.C.E. Rivalry between the Pergamene and [[Alexandrian library|Alexandrian libraries]] had resulted in the suspension of [[papyrus]] exports from [[Egypt]]. In response the Pergamenes developed [[parchment]] from [[sheepskin]]; because of the much greater expense it was necessary to write on both sides of the page. The [[Romans]] used similar precursors made of reusable wax-covered tablets of wood for taking notes and other informal writings. The first recorded Roman use of the codex for literary works dates from the late first century C.E., when [[Martial]] experimented with the format. At that time the [[scroll]] was the dominant medium for literary works and would remain dominant for secular works until the fourth century. [[Julius Caesar]], traveling in Gaul, found it useful to fold his scrolls [[concertina]]-style for quicker reference, as the [[Chinese]] also later did. As far back as the early second century, there is evidence that the codex—usually of papyrus—was the preferred format among [[Christianity|Christians]]: In the library of the [[Villa of the Papyri]], [[Herculaneum]] (buried in 79 C.E.), all the texts (Greek literature) are scrolls; in the [[Nag Hammadi]] "library," secreted about 390 C.E., all the texts (Gnostic Christian) are codices. The earliest surviving fragments from codices come from Egypt and are variously dated (always tentatively) towards the end of the first century or in the first half of the second. This group includes the [[Rylands Library Papyrus P52]], containing part of [[St John's Gospel]], and perhaps dating from between 125 and 160.<ref>Turner, ''The Typology of the Early Codex'' (University of Pennsylvania, 1977).</ref> | ||

| − | In [[Western culture#Foundations|Western culture]] the codex gradually replaced the scroll. | + | In [[Western culture#Foundations|Western culture]], the codex gradually replaced the scroll. From the fourth century, when the codex gained wide acceptance, to the [[Carolingian Renaissance]] in the eighth century, many works that were not converted from scroll to codex were lost. The codex was an improvement over the scroll in several ways. It could be opened flat at any page, allowing easier reading; the pages could be written on both [[recto]] and [[verso]]; and the codex, protected within its durable covers, was more compact and easier to transport. |

| − | + | The codex also made it easier to organize documents in a [[library]] because it had a stable spine on which the title of the book could be written. The spine could be used for the [[incipit]], before the concept of a proper title was developed, during medieval times. | |

| − | The codex also made it easier to organize documents in a [[library]] because it had a stable spine on which the title of the book could be written. | ||

Although most early codices were made of [[papyrus]], papyrus was fragile and supplies from Egypt, the only place where papyrus grew, became scanty; the more durable [[parchment]] and [[vellum]] gained favor, despite the cost. | Although most early codices were made of [[papyrus]], papyrus was fragile and supplies from Egypt, the only place where papyrus grew, became scanty; the more durable [[parchment]] and [[vellum]] gained favor, despite the cost. | ||

| Line 24: | Line 32: | ||

In Asia, the scroll remained standard for far longer than in the West. The [[Jewish]] religion still retains the [[Torah]] scroll, at least for ceremonial use. | In Asia, the scroll remained standard for far longer than in the West. The [[Jewish]] religion still retains the [[Torah]] scroll, at least for ceremonial use. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

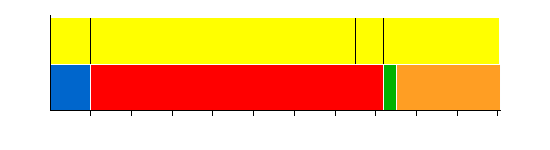

| − | + | <timeline> | |

| − | + | # définition de la taille de la frise | |

| − | + | ImageSize = width:550 height:150 # taille totale de l'image : largeur, hauteur | |

| − | + | PlotArea = width:450 height:95 left:50 bottom:40 # taille réelle de la frise au sein de l'image | |

| − | + | DateFormat = yyyy # format des dates utilisées | |

| − | + | Period = from:-200 till:2010 # laps de temps (de ... à ...) | |

| − | + | TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal # orientation de la frise (verticale ou horizontale) | |

| − | + | ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:200 start:0 # incrément temporel (majeur) | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | # définition des données de la frise | |

| − | + | PlotData= | |

| + | # définition de la première barre: 45 pixels de large, etc. | ||

| + | bar:Book color:yellow width:45 mark:(line,white) align:left fontsize:M | ||

| + | from: start till:2007 shift:(-15,30) | ||

| + | at:0 mark:(line, black) shift:(0,30) textcolor:black fontsize:8 text:[[Parchment]] | ||

| + | at:1300 mark:(line, black) shift:(-15,30) textcolor:black fontsize:8 text:[[Paper]] | ||

| + | at:1440 mark:(line, black) shift:(20,30) textcolor:black fontsize:8 text:[[Typography]] | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color: blue width:45 mark:(line,white) align:left fontsize:M | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color:blue from: start till: 0 shift:(-20,-60) textcolor:black text:[[Papyrus]] | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color:red from: 0 till: 1440 shift:(-15,-60) textcolor:black text:[[Codex]] | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color:green from: 1440 till: 1500 shift:(-65,-60) textcolor:black text:[[Incunabulum]] | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color:orange from: 1500 till: 2010 shift:(-20,-60)text:Modern book | ||

| + | </timeline> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Socio-historical contexts of codex in early [[Christianity]]== | ||

| + | [[Scroll]]s were the dominant form of a [[book]] before codices became popular. One of practical advantages of codex is easy access to the page one wants to see. Because multiple sheets are bound together at one end like today's books, users can open and go to the desired page without going through pages preceding it. In scroll, however, users have to go through all the way in order to get to the desired page. This difference between scrolls and codices is, in today's information environment, analogous to that of [[analog]] storage device such as [[audio tape]] and [[microfilm]] and [[digital]] storage devise such as [[CD]]s, [[DVD]]s, and [[computer]] [[hard drive]]. While, in analog devise, users have to go through other parts in order to get to the desired point, users can directly get to the point where information is stored in a digital devise. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Practical advantage of codex is one of the reasons whey the codex replaced the scroll. By the fifth century, codex became dominant and replaced scroll. Early [[Christianity|Christians]], however, embraced codex much earlier. While majority of non-Christian sources before 300 C.E. were all stored in scrolls, almost all Christian sources before 300 C.E. were stored in codices.<ref>Larry Hurtado, The coming of the codex, Centre for the History of the Book, CHB Newsletter, 2002.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the reasons why Christians used codex in sharp contrast to the use of scroll in [[Judaism]]. Some scholars such as Larry Hurtado argues that Christians used codex in order to clearly indicate the provenance of their writings in order to distinguish those by Jewish scholars: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>Among the Christian writings intentionally copied on fresh scrolls are [[theology|theological]] tractates, [[liturgy|liturgical]] texts, and [[magic]]al writings. Christian copies of [[Old Testament]] writings, on the other hand, and copies of those texts that came to form part of the [[New Testament]], are written almost entirely as codices…. One reason for this may have been to indicate that a given copy of a scriptural writing came from Christian hands. Theological arguments between Christians and Jews often focused on the text of Old Testament writings, each accusing the other of interfering with the text to remove offending material or insert passages in order to legitimize their respective beliefs. Before printing presses and publishers' imprints, it is possible that the codex served to indicate to Christian readers that a particular copy had a sound [[provenance]].<ref>Ibid.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | While the practical advantages of the codex format contributed to its increasing use, the rise of Christianity in the [[Roman Empire]] may have helped spread its popularity. | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

*[[Aztec codices]] | *[[Aztec codices]] | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Book]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[[Maya codices]] | *[[Maya codices]] | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Paper]] |

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Parchment]] |

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Scroll]] |

| + | *[[Vellum]] | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 132: | Line 82: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Hanson, K.C. [http://www.kchanson.com/papyri.html | + | *Hanson, K.C. [http://www.kchanson.com/papyri.html ''Catalogue of New Testament Papyri & Codices 2nd-10th Centuries.''] Retrieved November 7, 2008. |

| + | *Diringer, David. ''The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental.'' New York: Dover Publications, 1982. ISBN 0486242439. | ||

| + | *Hurtado, Larry. [http://www.hss.ed.ac.uk/chb/chbn2002_4.htm ''The coming of the codex.''] Center for the History of the Book, CHB Newsletter—2002. Retrieved October 8, 2008. | ||

| + | *Hurtado, Larry W. ''The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins.'' Grand Rapids, Mich: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co, 2006. ISBN 9780802828958. | ||

| + | *Roberts, Colin H., and Theodore C. Skeat. ''The Birth of the Codex.'' London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1989. ISBN 9780197260616. | ||

| + | *Turner, E.G. ''The Typology of the Early Codex''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1977. ISBN 9780812276961. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | All links | + | All links retrieved January 7, 2024. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [ | + | *[http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/gopher/other/journals/kraftpub/Christianity/Canon The Codex and Canon Consciousness - Draft paper by Robert Kraft on the change from scroll to codex] |

| − | [ | + | *[http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/scroll/scrollcodex.html Encyclopaedia Romana: "Scroll and codex"] |

| − | {{credits| | + | [[Category:library and information science]] |

| + | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

| + | {{credits|Codex|240708365|Codicology|241574512|Palaeography|238603460}} | ||

Latest revision as of 22:22, 7 January 2024

A codex (Latin for block of wood, book; plural codices) is a book in the format used for modern books, with separate pages normally bound together and given a cover. Although the modern book is technically a codex, the term is used only for manuscripts. The codex was a Roman invention that replaced the scroll, which was the first book form in all Eurasian cultures.

While non-Christian traditions such as Judaism used scrolls, early Christians used codices before it became popular. Christian scholars seemed to have used codices in order to distinguish their writings from Jewish scholarly works due to controversy and dispute particularly regarding the Old Testament and other theological writings. By the fifth century, the codex became the primary writing medium for a general use. While the practical advantages of the codex format contributed to its increasing use, the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire may have helped spread its popularity.

Overview

Although technically any modern paperback is a codex, the term is used only for manuscript (hand-written) books, produced from Late Antiquity through the Middle Ages. The scholarly study of manuscripts from the point of view of the bookmaking craft is called codicology. The study of ancient documents in general is called paleography.

Codicology (from Latin cōdex, genitive cōdicis, "notebook, book;" and Greek -λογία, -logia) is the study of books as physical objects, especially manuscripts written on parchment in codex form. It is often referred to as 'the archaeology of the book', concerning itself with the materials (parchment, sometimes referred to as membrane or vellum, paper, pigments, inks and so on), and techniques used to make books, including their binding.

Palaeography, palæography (British), or paleography (American) (from the Greek παλαιός palaiós, "old" and γράφειν graphein, "to write") is the study of ancient handwriting, and the practice of deciphering and reading historical manuscripts.[1]

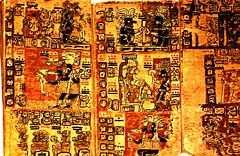

New World codices were written as late as the 16th century (see Maya codices and Aztec codices). Those written before the Spanish conquests seem all to have been single long sheets folded concertina-style, sometimes written on both sides of the local amatl paper. So, strictly speaking they are not in codex format, but they more consistently have "Codex" in their usual names than do other types of manuscript.

The codex was an improvement upon the scroll, which it gradually replaced, first in the West, and much later in Asia. The codex in turn became the printed book, for which the term is not used. In China, books were already printed but only on one side of the paper, and there were intermediate stages, such as scrolls folded concertina-style and pasted together at the back.[2]

History

The basic form of the codex was invented in Pergamon in the third century B.C.E. Rivalry between the Pergamene and Alexandrian libraries had resulted in the suspension of papyrus exports from Egypt. In response the Pergamenes developed parchment from sheepskin; because of the much greater expense it was necessary to write on both sides of the page. The Romans used similar precursors made of reusable wax-covered tablets of wood for taking notes and other informal writings. The first recorded Roman use of the codex for literary works dates from the late first century C.E., when Martial experimented with the format. At that time the scroll was the dominant medium for literary works and would remain dominant for secular works until the fourth century. Julius Caesar, traveling in Gaul, found it useful to fold his scrolls concertina-style for quicker reference, as the Chinese also later did. As far back as the early second century, there is evidence that the codex—usually of papyrus—was the preferred format among Christians: In the library of the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum (buried in 79 C.E.), all the texts (Greek literature) are scrolls; in the Nag Hammadi "library," secreted about 390 C.E., all the texts (Gnostic Christian) are codices. The earliest surviving fragments from codices come from Egypt and are variously dated (always tentatively) towards the end of the first century or in the first half of the second. This group includes the Rylands Library Papyrus P52, containing part of St John's Gospel, and perhaps dating from between 125 and 160.[3]

In Western culture, the codex gradually replaced the scroll. From the fourth century, when the codex gained wide acceptance, to the Carolingian Renaissance in the eighth century, many works that were not converted from scroll to codex were lost. The codex was an improvement over the scroll in several ways. It could be opened flat at any page, allowing easier reading; the pages could be written on both recto and verso; and the codex, protected within its durable covers, was more compact and easier to transport.

The codex also made it easier to organize documents in a library because it had a stable spine on which the title of the book could be written. The spine could be used for the incipit, before the concept of a proper title was developed, during medieval times.

Although most early codices were made of papyrus, papyrus was fragile and supplies from Egypt, the only place where papyrus grew, became scanty; the more durable parchment and vellum gained favor, despite the cost.

The codices of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica had the same form as the European codex, but were instead made with long folded strips of either fig bark (amatl) or plant fibers, often with a layer of whitewash applied before writing.

In Asia, the scroll remained standard for far longer than in the West. The Jewish religion still retains the Torah scroll, at least for ceremonial use.

Socio-historical contexts of codex in early Christianity

Scrolls were the dominant form of a book before codices became popular. One of practical advantages of codex is easy access to the page one wants to see. Because multiple sheets are bound together at one end like today's books, users can open and go to the desired page without going through pages preceding it. In scroll, however, users have to go through all the way in order to get to the desired page. This difference between scrolls and codices is, in today's information environment, analogous to that of analog storage device such as audio tape and microfilm and digital storage devise such as CDs, DVDs, and computer hard drive. While, in analog devise, users have to go through other parts in order to get to the desired point, users can directly get to the point where information is stored in a digital devise.

Practical advantage of codex is one of the reasons whey the codex replaced the scroll. By the fifth century, codex became dominant and replaced scroll. Early Christians, however, embraced codex much earlier. While majority of non-Christian sources before 300 C.E. were all stored in scrolls, almost all Christian sources before 300 C.E. were stored in codices.[4]

One of the reasons why Christians used codex in sharp contrast to the use of scroll in Judaism. Some scholars such as Larry Hurtado argues that Christians used codex in order to clearly indicate the provenance of their writings in order to distinguish those by Jewish scholars:

Among the Christian writings intentionally copied on fresh scrolls are theological tractates, liturgical texts, and magical writings. Christian copies of Old Testament writings, on the other hand, and copies of those texts that came to form part of the New Testament, are written almost entirely as codices…. One reason for this may have been to indicate that a given copy of a scriptural writing came from Christian hands. Theological arguments between Christians and Jews often focused on the text of Old Testament writings, each accusing the other of interfering with the text to remove offending material or insert passages in order to legitimize their respective beliefs. Before printing presses and publishers' imprints, it is possible that the codex served to indicate to Christian readers that a particular copy had a sound provenance.[5]

While the practical advantages of the codex format contributed to its increasing use, the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire may have helped spread its popularity.

See also

- Aztec codices

- Book

- Maya codices

- Paper

- Parchment

- Scroll

- Vellum

Notes

- ↑ "Palaeography," Oxford English Dictionary.

- ↑ Colin Chinnery. International Dunhuang Project—Several intermediate Chinese bookbinding forms from the C10th. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ↑ Turner, The Typology of the Early Codex (University of Pennsylvania, 1977).

- ↑ Larry Hurtado, The coming of the codex, Centre for the History of the Book, CHB Newsletter, 2002.

- ↑ Ibid.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hanson, K.C. Catalogue of New Testament Papyri & Codices 2nd-10th Centuries. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- Diringer, David. The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental. New York: Dover Publications, 1982. ISBN 0486242439.

- Hurtado, Larry. The coming of the codex. Center for the History of the Book, CHB Newsletter—2002. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- Hurtado, Larry W. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Grand Rapids, Mich: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co, 2006. ISBN 9780802828958.

- Roberts, Colin H., and Theodore C. Skeat. The Birth of the Codex. London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1989. ISBN 9780197260616.

- Turner, E.G. The Typology of the Early Codex. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1977. ISBN 9780812276961.

External links

All links retrieved January 7, 2024.

- The Codex and Canon Consciousness - Draft paper by Robert Kraft on the change from scroll to codex

- Encyclopaedia Romana: "Scroll and codex"

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.