Difference between revisions of "Bullet" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Design) |

m (→Materials) |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

==Materials== | ==Materials== | ||

| + | [[Image:Bullet.jpg|thumb|430px|left]] | ||

Bullets for blackpowder, or muzzleloading firearms, were classically molded from pure lead. This worked well for low speed bullets, fired at velocities of less than 300 m/s (1000 ft/s). For slightly higher speed bullets fired in modern firearms, a harder [[alloy]] of lead and tin or [[typesetter]]'s lead (used to mould [[Linotype]]) works very well. For even higher speed bullet use, jacketed coated lead bullets are used. The common element in all of these, lead, is widely used because it is highly dense, thereby providing a high amount of mass—and thus, [[kinetic energy]]—for a given volume. Lead is also relatively cheap, easy to obtain, and melts at a low temperature, making it easy to use in fabricating bullets. | Bullets for blackpowder, or muzzleloading firearms, were classically molded from pure lead. This worked well for low speed bullets, fired at velocities of less than 300 m/s (1000 ft/s). For slightly higher speed bullets fired in modern firearms, a harder [[alloy]] of lead and tin or [[typesetter]]'s lead (used to mould [[Linotype]]) works very well. For even higher speed bullet use, jacketed coated lead bullets are used. The common element in all of these, lead, is widely used because it is highly dense, thereby providing a high amount of mass—and thus, [[kinetic energy]]—for a given volume. Lead is also relatively cheap, easy to obtain, and melts at a low temperature, making it easy to use in fabricating bullets. | ||

| Line 70: | Line 71: | ||

*A variation of the jacketed lead bullet is the H-type. Here the jacket has a two cavities, a front one and a rear one. The forward part covers the front of the bullet and behaves as a conventional exposed-lead softpoint. The rear part is filled with lead and behaves like a full metal cased bullet. On impact, such a bullet mushrooms at the front, but the mushrooming cannot go beyond the middle part of the bullet, so the bullet can be counted upon to retain a substantial amount of its weight and to penetrate deeply. The German H-Mantel, the Nosler Partition, and the Swift A-Frame are examples of this design. | *A variation of the jacketed lead bullet is the H-type. Here the jacket has a two cavities, a front one and a rear one. The forward part covers the front of the bullet and behaves as a conventional exposed-lead softpoint. The rear part is filled with lead and behaves like a full metal cased bullet. On impact, such a bullet mushrooms at the front, but the mushrooming cannot go beyond the middle part of the bullet, so the bullet can be counted upon to retain a substantial amount of its weight and to penetrate deeply. The German H-Mantel, the Nosler Partition, and the Swift A-Frame are examples of this design. | ||

| − | * [[armor piercing bullet|Armor Piercing]]: Jacketed designs where the core material is a very hard, high-density metal such as [[tungsten]], [[tungsten carbide]], [[depleted uranium]], or [[steel]]. A pointed tip is often used, but a flat tip on the penetrator portion is generally more effective.<ref> | + | * [[armor piercing bullet|Armor Piercing]]: Jacketed designs where the core material is a very hard, high-density metal such as [[tungsten]], [[tungsten carbide]], [[depleted uranium]], or [[steel]]. A pointed tip is often used, but a flat tip on the penetrator portion is generally more effective. <ref> Hughes, David R.</ref> |

* [[Tracer ammunition|Tracer]]: These have a hollow back, filled with a flare material. Usually this is a mixture of [[magnesium]] perchlorate, and [[strontium]] salts to yield a bright red color, although other materials providing other colors have also sometimes been used. Tracer material burns out after a certain amount of time. Such ammunition is useful to the shooter as a means of verifying how close the point of aim is to the actual point of impact, and for learning how to point shoot moving targets with rifles. The flight characteristics of tracer rounds differ from normal bullets, decreasing in altitude sooner than other bullets, as their mass decreases over time due to the burning of the flare material. | * [[Tracer ammunition|Tracer]]: These have a hollow back, filled with a flare material. Usually this is a mixture of [[magnesium]] perchlorate, and [[strontium]] salts to yield a bright red color, although other materials providing other colors have also sometimes been used. Tracer material burns out after a certain amount of time. Such ammunition is useful to the shooter as a means of verifying how close the point of aim is to the actual point of impact, and for learning how to point shoot moving targets with rifles. The flight characteristics of tracer rounds differ from normal bullets, decreasing in altitude sooner than other bullets, as their mass decreases over time due to the burning of the flare material. | ||

| Line 215: | Line 216: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | + | ||

==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

| − | *Barnes, Frank, ''Cartridges of the World''. Iola, WI: Gun Digest Books, c/o F&W Publications, Inc., 2006. ISBN 0896892972 | + | * Barnes, Frank, ''Cartridges of the World''. Iola, WI: Gun Digest Books, c/o F&W Publications, Inc., 2006. ISBN 0896892972 |

| − | *Johnson, Steve, ed. | + | * Johnson, Steve, ed.''Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading: Seventh Edition'', Grand Island, Nebraska: Hornady Manufacturing Company, Inc., 2006. |

| − | *''Lapua Shooting And Reloading Manual 2nd Edition''. Lapua, Finland: Lapua, 2000 | + | * ''Lapua Shooting And Reloading Manual 2nd Edition''. Lapua, Finland: Lapua, 2000 |

| − | *''Lyman 48th Edition Reloading Handbook''. Middletown, CT: Lyman Products Corp., 2003 | + | * ''Lyman 48th Edition Reloading Handbook''. Middletown, CT: Lyman Products Corp., 2003 |

| − | *''Nosler Reloading Guide, Fifth Edition.'' Bend, Oregon: Nosler, Inc., 2002. | + | * ''Nosler Reloading Guide, Fifth Edition.'' Bend, Oregon: Nosler, Inc., 2002. |

| − | *Ramage, Ken, ed., ''Handloader's Digest, 18th Edition''. Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2002. ISBN 087349475X | + | * Ramage, Ken, ed., ''Handloader's Digest, 18th Edition''. Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2002. ISBN 087349475X |

| − | *''Speer Reloading Manual, Number 14''. Lewiston, Idaho: Speer, Inc., 2007. | + | * ''Speer Reloading Manual, Number 14''. Lewiston, Idaho: Speer, Inc., 2007. |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 21:51, 9 August 2007

- For other uses, see Bullet (disambiguation).

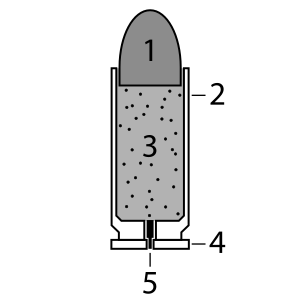

A bullet is a solid projectile propelled by a firearm or air gun and is normally made from metal (usually lead). A bullet (in contrast to a shell) does not contain explosives, and damages the intended target solely by imparting kinetic energy upon impact.

The word "bullet" is sometimes used incorrectly to refer to the loaded combination of bullet, cartridge case, gunpowder, and primer (also sometimes called a percussion cap), but this is more properly known as a cartridge or round. The Oxford English Dictionary definition of a bullet is "a projectile of lead ... for firing from a rifle, revolver etc,"[1], but nowadays bullets are sometimes made of materials other than lead. All-copper bullets are now available and are sometimes used in high powered rifles for hunting, especially of large animals. Plastic or rubber bullets are used for crowd control or other purposes. Bullets of iron, steel, bismuth, depleted uranium, or other metals have also sometimes been made and used.

What all bullets have in common is that they are single projectiles—as opposed to birdshot or buckshot, multiple small balls fired together as a shot charge—designed to be fired from a firearm, usually a rifle or pistol, but also a small caliber machine gun. The large projectiles fired from military weapons, such as tanks, cannons, or naval guns, are not usually called bullets.

History

The first bullets

The history of bullets parallels the history of firearms. Advances in one either resulted from or precipitated advances in the other. Originally, bullets were round metallic or stone balls placed in front of an explosive charge of gunpowder at the end of a closed tube. As firearms became more technologically advanced, from 1500 to 1800, bullets changed very little. They remained simple round lead balls, called rounds, differing only in their diameter.

"Bullet" is derived from the French word boulette which roughly means "little ball." The original musket bullet was a spherical lead ball wrapped in a loosely-fitted paper patch which served to hold the bullet in the barrel firmly upon the powder. The muzzle-loading rifle, needed a closely fitting ball to take its barrel's rifling grooves. This made loading difficult, particularly when the bore of the barrel was dirty from previous firings. For this reason, early rifles were not generally used for military purposes.

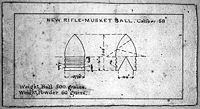

Shaped bullets

The first half of the nineteenth century saw a distinct change in the shape and function of the bullet. One of the first pointed or "bullet-shaped" bullets was designed by Captain John Norton of the British Army in 1823. Norton's bullet had a hollow base which expanded under pressure to catch the rifling grooves at the moment of being fired. However, because spherical bullets had been in use for the last 300 years, the British Board of Ordnance rejected it.

Renowned English gunsmith William Greener invented the Greener bullet in 1836. It was very similar to Norton's bullet except that the hollow base of the bullet was fitted with a wooden plug which more reliably forced the base of the bullet to expand and catch the rifling. Tests proved that Greener's bullet was extremely effective. However, it too was rejected for military use because, being two parts, it was judged as being too complicated to produce.

The soft lead bullet that came to be known as the Minié ball, (or minnie ball) was first introduced in 1847 by Claude Étienne Minié (1814? - 1879), a captain in the French Army. It was nearly identical to the Greener bullet. This bullet was conical in shape with a hollow cavity in the rear, which was fitted with a small iron cap instead of a wooden plug. When fired, the iron cap would force itself into the hollow cavity at the rear of the bullet, thereby expanding the sides of the bullet to grip and engage the barrel's rifling. In 1855, the British adopted the Minié ball for their Enfield rifles.

The Minié ball first saw widespread use in the American Civil War. Roughly 90 percent of the battlefield casualties in this war were caused by Minié balls fired from rifles.

Between 1854 and 1857, Sir Joseph Whitworth conducted a long series of rifle experiments, and proved the advantages of a smaller bore and, in particular, of an elongated bullet. The Whitworth bullet was made to fit the grooves of the rifle mechanically. The Whitworth rifle was never adopted by the government, although it was used extensively for match purposes and target practice between 1857 and 1866.

About 1862, W. E. Metford carried out an exhaustive series of experiments on bullets and rifling and soon invented a system of light rifling with increasing spiral, together with a hardened bullet. The combined result of these inventions was that in December 1888 the Lee Metford small-bore (".303") rifle, Mark I, was adopted for the British army.

The modern bullet

The next important change in the history of the rifle bullet occurred in 1883, when Major Rubin, director of the Swiss Laboratory at Thun, invented the copper-jacketed bullet; an elongated bullet with a lead core in a copper envelope or jacket.

For relatively low muzzle velocities—around 800 feet per second up to 1300 feet per second—a bullet of pure lead will work, although lead deposits will tend to build up inside the barrel. As the velocity increases, the problem of barrel "leading" increases, as does the melting of the lead bullet from the heat of firing and the friction of moving through the barrel. One way to solve that problem is to add some other metal—typically tin or antimony—to the lead, making an alloy that is harder and has a higher melting temperature than pure lead. This works for velocities up to about 2700 feet per second. However, the copper-jacketed bullet allows much higher muzzle velocities than lead alone. Today, except for low powered ammunition, nearly all commercially made rounds for rifles and handguns—especially ammunition intended for use in hunting or target shooting—has jacketed bullets.

A spitzer is a German name for a tapered, aerodynamic bullet design used in most intermediate and high-powered rifle cartridges.

Advances in aerodynamics led to the pointed or spitzer bullet. By the beginning of the twentieth century, most world armies had begun to transition to spitzer bullets. These bullets flew for greater distances, carried more energy because they had less air resistance, and were more accurate that their predecessors. Spitzer bullets, especially combined with machine guns, increased the lethality of the battlefield exponentially.

The final advancement in bullet shape occurred with the development of the boat tail, which is a streamlined base for bullets. A vacuum is created when air strata moving at high speed passes over the end of a bullet. The streamlined boat tail design aims to eliminate this drag-inducing vacuum by allowing the air to flow alongside the surface of the tapering end, thus eliminating the need for air to turn around the 90-degree angle normally formed by the end of shaped bullets. The resulting aerodynamic advantage is currently seen as the optimum shape for bullet technology.

Today some bullets for high powered rifles are given a thin film or coating of some material—usually molybdenum disulfide, usually known as moly—over their copper jackets to further ease their travel down the rifle barrel and decrease the build-up of copper fouling in the bore.

Design

1. the bullet itself, which serves as the projectile;

2. the casing, which holds all parts together;

3. the propellant, for example gunpowder or cordite;

4. the rim, part of the casing used for loading;

5. the primer, which ignites the propellant.

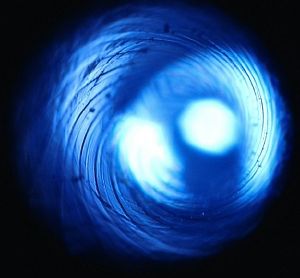

Bullet designs have to solve two primary problems. They must first form a seal with the gun's bore. The worse the seal, the more gas generated by the rapid combustion of the propellant charge that leaks past the bullet reducing the efficiency. The bullet must also engage the rifling without damaging the gun's bore. Bullets must have a surface which will form this seal without causing excessive friction. What happens to a bullet inside the bore is termed internal ballistics. A bullet must also be consistent with the next bullet so that shots may be fired accurately.

Once it leaves the barrel, it is governed by external ballistics. Here, the bullet's shape is important for aerodynamics, as is the rotation imparted by the rifling. Rotational forces stabilize the bullet gyroscopically as well as aerodynamically. Any asymmetry in the bullet is largely canceled as it spins. With smooth-bore firearms, a spherical shape was optimum because no matter how it was oriented, it presented a uniform front. These unstable bullets tumbled erratically, but the aerodynamic shape changed little giving moderate accuracy. Generally, bullet shapes are a compromise between aerodynamics, interior ballistics necessities, and terminal ballistics requirements. Another method of stabilization is for the center of mass of the bullet to be as far forward as practical as in the minnie ball or the shuttlecock. This allows the bullet to fly front-forward by means of aerodynamics.

What happens to the bullet on impact is dictated partly by the design of the bullet and partly by what it hits and how it hitsit. Bullets are generally designed to penetrate, deform, and/or break apart. For a given material and bullet, which of these happens is determined partly by the strike velocity.

Actual bullet shapes are many and varied, and an array of them can be found in most reloading manuals. RCBS, Lyman, Lee, Saeco and other makers offer bullet molds in many calibers and shapes to create many different molded lead or lead alloy bullet designs, starting with the basic round ball. Also, by using a bullet mold, bullets can be made at home for reloading one's own ammunition, where local laws allow. Hand-casting, however, is only time and cost effective for solid lead or lead alloy bullets. Cast and jacketed bullets are also commercially available from numerous manufacturers for hand loading and are much more convenient than casting bullets from bulk lead.

In practice, most handloaders for rifles and handguns buy bullets supplied by one of many manufacturers, including Barnes, Berger, Hornady, Nosler, Remington, Sierra, Speer, and others in the U.S., Woodleigh in Australia, Lapua or Norma in Europe, or various other European orSouth African manufacturers. Bullets are made in numerous other countries also, including China and Russia, but are generally available only in loaded ammunition—sometimes only to military users—and are not sold for handloading use.

Materials

Bullets for blackpowder, or muzzleloading firearms, were classically molded from pure lead. This worked well for low speed bullets, fired at velocities of less than 300 m/s (1000 ft/s). For slightly higher speed bullets fired in modern firearms, a harder alloy of lead and tin or typesetter's lead (used to mould Linotype) works very well. For even higher speed bullet use, jacketed coated lead bullets are used. The common element in all of these, lead, is widely used because it is highly dense, thereby providing a high amount of mass—and thus, kinetic energy—for a given volume. Lead is also relatively cheap, easy to obtain, and melts at a low temperature, making it easy to use in fabricating bullets.

- Lead: Simple cast, extruded, swaged, or otherwise fabricated lead slugs are the simplest form of bullets. At speeds of greater than 300 m/s (1000 ft/s) common in most handguns, lead is deposited in rifled bores at an ever-increasing rate. Alloying the lead with a small percentage of tin and/or antimony serves to reduce this effect, but grows less effective as velocities are increased. A cup made of harder metal, such as copper, placed at the base of the bullet and called a gas check, is often used to decrease lead deposits by protecting the rear of the bullet against melting when fired at higher pressures, but this too does not solve the problem at higher velocities.

- Jacketed Lead: Bullets intended for even higher-velocity applications generally have a lead core that is jacketed or plated with cupro-nickel, copper alloys, or steel; the thin layer of harder copper protects the softer lead core when the bullet is passing through the barrel and during flight, which allows delivering the bullet intact to the target. There, the heavy lead core delivers its kinetic energy to the target. Full Metal Jacket bullets have the front and sides of the bullet completely encased in the harder metal jacket. Some bullet jackets do not extend to the front of the bullet to aid in expansion and increase lethality. These are called soft points or, if there is a cavity in the front of the projectile, hollow point bullets. More recent examples of jacketed bullets may have a metal or a polycarbonate plastic insert at the tip that serves to protects the tip from deformation and act as an expansion-starter on bullet impact. Still another variation is the bonded bullet, in which thre is a strong chemical bond between the copper jacket and the lead core of the bullet so that the bullet does not come apart or disintegrate on impact. (Nosler Accubond and Hornady Interbond bullets are examples of bonded bullets.) Steel bullets are often plated with copper or other metals for additional corrosion resistance during long periods of storage. Synthetic jacket materials such as nylon and teflon have been used with some success.

- A variation of the jacketed lead bullet is the H-type. Here the jacket has a two cavities, a front one and a rear one. The forward part covers the front of the bullet and behaves as a conventional exposed-lead softpoint. The rear part is filled with lead and behaves like a full metal cased bullet. On impact, such a bullet mushrooms at the front, but the mushrooming cannot go beyond the middle part of the bullet, so the bullet can be counted upon to retain a substantial amount of its weight and to penetrate deeply. The German H-Mantel, the Nosler Partition, and the Swift A-Frame are examples of this design.

- Armor Piercing: Jacketed designs where the core material is a very hard, high-density metal such as tungsten, tungsten carbide, depleted uranium, or steel. A pointed tip is often used, but a flat tip on the penetrator portion is generally more effective. [2]

- Tracer: These have a hollow back, filled with a flare material. Usually this is a mixture of magnesium perchlorate, and strontium salts to yield a bright red color, although other materials providing other colors have also sometimes been used. Tracer material burns out after a certain amount of time. Such ammunition is useful to the shooter as a means of verifying how close the point of aim is to the actual point of impact, and for learning how to point shoot moving targets with rifles. The flight characteristics of tracer rounds differ from normal bullets, decreasing in altitude sooner than other bullets, as their mass decreases over time due to the burning of the flare material.

- Incendiary: These bullets are made with an explosive or flammable mixture in the tip that is designed to ignite on contact with a target. The intent is to ignite fuel or munitions in the target area, thereby adding to the destructive power of the bullet itself.

- Frangible: Designed to disintegrate into tiny particles upon impact to minimize their penetration for reasons of range safety, to limit environmental impact, or to limit the shoot-through danger behind the intended target. An example is the Glaser Safety Slug.

- Non Toxic: Bismuth, tungsten, steel, and other exotic bullet alloys prevent release of toxic lead into the environment. Regulations in several countries mandate the use of non-toxic projectiles especially when hunting waterfowl. It has been found that birds swallow small lead shot for their gizzards to grind food (as they would swallow pebbles of similar size), and the effects of lead poisoning by constant grinding of lead pellets against food means lead poisoning effects are magnified. Such concerns apply primarily to shotguns, firing shells and not bullets, but reduction of hazardous substances (RoHS) legislation has also been applied to bullets on occasion to reduce the impact of lead on the environment at shooting ranges.

- Practice: Made from lightweight materials like rubber, Wax, wood, plastic, or lightweight metal, practice bullets are intended for short-range target work, only. Because of their weight and low velocity, they have limited range.

- Less Lethal, or Less than Lethal: Rubber bullets, plastic bullets, and beanbags are designed to be non-lethal, for example for use in riot control. They are generally low velocity and are fired from shotguns, grenade launchers, paintball guns, or specially-designed firearms and air gun devices.

- Blanks: Wax, paper, plastic, and other materials are used to simulate live gunfire and are intended only to hold the powder in a blank cartridge and to produce noise. The 'bullet' may be captured in a purpose-designed device or it may be allowed to expend what little energy it has in the air. Some blank cartridges are crimped or closed at the end and do not contain any bullet.

Measurements for Bullets

Specifications for a bullet are usually given in three dimensions: (1) Weight of the bullet. In the U.S. and some parts of the former British Commonwealth, this is usually given in grains (one avoirdupois pound = 7000 grains), but elsewhere in the world it is given in grams (one gram = 15.43 grains). (2) Diameter of the bullet. In the US and parts of the British Commonwealth this is usually expressed in thousandths of an inch, but elsewhere in the world in millimeters (one inch = 25.4 mm). (3) Type and shape of the bullet, such as "lead round nose," or "jacketed round nose," or "jacketed spitzer hollow point," or "full metal jacket round nose" or whatever other designation may be pertinent for a particular bullet.

There are two other numerical parameters that are important for bullets: the sectional density and the ballistic coefficient. The sectional density of a bullet is the ratio of the weight of the bullet compared to its cross section. Thus regardless of the differing shape, two bullets of the same weight and diameter (caliber) will have the same sectional density even though one is a round nose and the other is a spitzer boattail. All other things being equal, a higher sectional density leads to greater penetration for a bullet.

The ballistic coefficient of a bullet is an expression of its ability to overcome air resistance in flight. In prctice, the ballistic coefficient will be a number greater than 0 and less than 1. The larger the number, the less the bullet will be slowed down by air resistance in flight. This means that for long range shooting it is useful to have bullets of high ballistic coefficient as they will retain their velocity better as they move through the air (i.e. they will shed velocity in flight at a lower rate than will bullets with a lower ballistic coefficient).

When a bullet is fired in a rifle or pistol, the lands of the barrel (the raised spiral ribs in the barrel that impart spin to the bullet when it is fired through that barrel) impart grooves in the jacket or the outside of the bullet, and if the bullet is recovered sufficiently intact, those grooves will be visible on it.

The diameter (caliber) of a bullet is especially important, as a bullet of a given caliber must be used in a rifle or pistol that has a barrel of that given caliber. A common caliber for small arms throughout the world, for example, is .30 caliber (7.62 mm). This means that the barrel has a hole of .300 inches in diameter before the rifling is cut or made into it. After the rifling (spiral grooves) is cut or impressed into the barrel, the diameter measured from the bottom of the grooves is generally .308 inches. This means that bullets for .30 caliber rifles actually measure .308 inches in diameter. Generally bullets for a given caliber are .007 or .008 inches larger than the bore diameter for that caliber. Bullets for a .270 rifle, for example, measure .277 inches in diameter. Bullets for a 7mm rifle measure .284 inches in diameter. Bullets for the .303 British service caliber measure .311 inches in diameter. Bullets for a .25 caliber rifle measure .257 inches in diameter.

There are, for example, many different .30 caliber rifles: the .30 carbine, the .30-30 Winchester, the .30-40 Krag, the .300 Savage, the .30-06 Springfield, the .308 Winchester (also known as the 7.62 NATO), the 7.62 X 39 (the original caliber of the AK 47 assault rifle), the 7.62 x 54R Russian (used in WWI and WWII vintage Russian military weapons), the .300 Holland & Holland magnum, the .308 Norma magnum, the .300 Winchester magnum, the .300 Weatherby Magnum, the 7.5 mm Schmidt Rubin (7.5 mm Swiss), and numerous others. These rifles differ greatly in power and thus in the velocity (and consequent power) that they impart to bullets, but they are alike in that they all use bullets that measure .308 in diameter.

Some caliber designations use the actual bullet diameter. Examples are the .308 Winchester, .338 Winchester Magnum, and the .375 Holland & Holland Magnum.

In the case of some calibers and cartridges, the designations are very confusing. In handguns, the 9mm (also known as 9mm Luger or 9mm Parabellum), .38 Special, .38 ACP, .38 Super, and .357 Magnum, for example, all use bullets that measure .357 in diameter.

With the German 8 x 57 mm (8 mm Mauser) military rifle, there were actually two different calibers: an earlier one using a bullet that measures .318 inches in diameter, and a later one using a .323 inch diameter bullet. The first is usually designated 8 x 57 J and the latter (the .323 one) is usually designated 8 x 57 S or 8 x 57 JS. Most of the service weapons of WWII were the S-type (.323 diameter).

In the case of .45 caliber pistol and revolver ammunition—.45 ACP, .45 Auto Rim, .45 Colt—the bullets measure .451 inches in diameter.

There are many more examples of even more confusing caliber and cartridge designations. An especially egregious one is the rifle known as the .404 Jeffery, a large caliber rifle suitable for elephant and other large animals; it actually uses a bullet that measures .423 inches in diameter!

Bullets for Hunting

Choosing a bullet for hunting requires consideration of numerous variables. The first is the caliber of the rifle: a bullet of the diameter to fit the given rifle caliber must be used.

The second is the size and type of animal to be hunted. Small light weight animals, such as deer of up to perhaps 200 pounds, can be killed quickly with bullets that open up or mushroom (their front peels back and the bullet resembles a mushroom stem and head) quickly; such animals do not need bullets that penetrate a great distance. Large animals such as moose or elk, weighing possibly 1000 pounds, are best taken with bullets that hold together and penetrate deeply before mushrooming. The largest game animals—such as elephant, Cape buffalo, and rhino—are often shot using full metal jacketed bullets because such animals are very tough and require bullets that do not deform at all in order that the bullet can penetrate to vital organs of the animal.

The third is the likely distance at which the animal will be shot. If the distance is short—100 yards or less—a round nose bullet may be the best choice. If the distance is long—200yards or more—a spitzer bullet is generally a better choice because such bullets retain their velocity better. At very long distances—300yards or more—a boattail bullet may be a good choice.

A fourth choice is bullet weight. In .30 caliber, for instance, bullets are available that weigh from 110 grains or less to 220 grains or more. Roughly speaking, the lighter weight bullets are best for smaller animals and the heavier ones for larger animals. Also, for any rifle or pistol, it can impart a higher muzzle velocity to a lighter bullet than a heavier one, but heavier bullets, all other things being equal, have a higher ballistic coefficient than lighter ones. Thus, at longer ranges, the retaining velocity of the heavier bullet may be greater than that of a corresponding lighter bullet.

If a shooter handloads (i.e. loads his or her own ammunition) he has the ability to choose any bullet of the appropriate caliber for whatever caliber rifle or pistol for which he is loading, and he can load it to a range of velocities, depending on the type and amount of gunpowder used in the load. If he does not handload—handloading is very popular in the United States and Canada, but less so in Europe and is actually forbidden in some countries of the world—he is restricted to whatever factory loaded ammunition he or she can find for his or her rifle or handgun.

Bullets for Target Shooting

Target shooters have a different set of requirements. They do not care about the penetration or performance of the bullet upon impact, but only on its accuracy. Thus they choose bullets that give them the best accuracy (i.e. that result in putting a series of shots as close together as possible) in their given rifle or handgun. In practice, most target bullets for high powered rifles are of hollow point boattail design. such bullets made specifically for target shooting perform well at both short and very long distances for target shooting purposes, but they are not recommended for hunting.

Some handgun shooters use what are called wad cutter bullets. Those have a front that is almost flat to the edge, and they perfom like a paper punch, making very distinct round holes in the target. Wad cutter bullets have very poor ballistic coefficients, but pistol shooters do not care about that as the distances at which pistol shooting occurs is usually short, about 25 yards or less.

Treaties

The Geneva Accords on Humane Weaponry and the Hague Convention prohibit certain kinds of ammunition for use by uniformed military personnel against those uniformed military personnel of opposing forces. These include projectiles which explode within an individual, poisoned and expanding bullets. Nothing in these treaties prohibits incendiary bullets (tracers) or the use of prohibited bullets on military equipment.

These treaties apply even to .22 LR bullets used in pistols. Hence, the High Standard HDM pistol, a .22 LR silenced pistol, had special bullets developed for it during World War II that were full metal jacketed, in place of the unjacketed simple lead bullets that are more commonly used in .22 LR pistols.

Bullet acronyms

- AP — Armor Piercing (has a steel or other hard metal core)

- ACC — Accelerator

- BBWC — Bevel Base Wadcutter

- BEB — Brass Enclosed Base

- BT — Boat-Tail

- BTHP — Boat Tail Hollow Point

- CB — Cast Bullet

- CL — Core-Lokt

- DEWC — Double Ended Wadcutter

- FMJ — Full Metal Jacket

- FN — Flat Nose

- FP — Flat Point

- FST — Fail Safe Talon

- GD — Gold Dot

- GDHP — Gold Dot Hollow Point

- GS — Golden Saber

- HBWC — Hollow Base Wadcutter

- HC — Hard Cast

- HP — Hollow Point

- HPJ — High Performance Jacketed

- HS — Hydra Shok

- J — Jacketed

- JFP — Jacketed Flat Point

- JHC — Jacketed Hollow Cavity

- JHP — Jacketed Hollow Point

- JSP — Jacketed Soft Point

- L — Lead

- L-T — Lead Combat

- L-T — Lead Target

- LFN — Long Flat Nose

- LFP — Lead Flat Point

- LHP — Lead Hollow Point

- LRN — Lead Round Nose

- LSWC — Lead Semi-Wadcutter

- LSWC-GC — Lead Semi-Wadcutter Gas Checked

- LWC — Lead WadCutter

- LTC — Lead Truncated Cone

- MC — Metal Cased

- MRWC — Mid-Range Wadcutter

- +P — Plus P (10-15% overpressure)

- +P+ — Plus P Plus (20-25% overpressure)

- PB — Lead Bullet

- PB — Parabellum

- PL — Power-Lokt

- PSP — Plated Soft Point

- PSP — Pointed Soft Point

- RN — Round Nose

- RNFP — Round Nose Flat Point

- RNL — Round Nosed Lead

- SJ — Semi Jacketed

- SJHP — Semi Jacketed Hollow Point

- SJSP — Semi-Jacketed Soft Point

- SP — Soft Point

- SP — Spire Point

- SPTZ — Spitzer

- ST — Silver Tip

- STHP — Silver Tip Hollow Point

- SWC — Semi Wadcutter

- SX — Super Explosive

- SXT — Supreme Expansion Talon

- TC — Truncated Cone

- TMJ — Total Metal Jacket

- VLD — Very Low Drag

- WC — Wadcutter

- WLN — Wide Long Nose

- WSM — Winchester Short Magnum

- WSSM — Winchester Super Short Magnum

- XTP — Extreme Terminal Performance

Figurative uses

The word for the bullet, usually because of its speed, is sometimes used figuratively, e.g.:-

- The Japanese Bullet Trains.

- Expressions such as "the brown bullet from Trinidad" for a very fast human runner athlete.

- The expression "bullet-headed" for a dolichocephalic shape of the human head.

- The term silver bullet, an extremely effective solution to a problem, comes from the modern addition to werewolf folklore that the monster is highly vulnerable to firearms using silver ammunition.

- The phrase "biting the bullet," meaning (usually mental) preparation for an unpleasant task or experience, refers to a patient doing precisely that to brace him- or herself for a painful medical procedure (such as the removal of another bullet or amputation of a limb) before the advent of anesthesia. This was frequently done on or behind a battlefield, where bullets would be readily available.

- The phrase "bullet" is used, particularly in the United Kingdom as a form of insult, if someone answers a question slowly, or is last to realize something considered obvious.[citation needed]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/bullet

- ↑ Hughes, David R.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Frank, Cartridges of the World. Iola, WI: Gun Digest Books, c/o F&W Publications, Inc., 2006. ISBN 0896892972

- Johnson, Steve, ed.Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading: Seventh Edition, Grand Island, Nebraska: Hornady Manufacturing Company, Inc., 2006.

- Lapua Shooting And Reloading Manual 2nd Edition. Lapua, Finland: Lapua, 2000

- Lyman 48th Edition Reloading Handbook. Middletown, CT: Lyman Products Corp., 2003

- Nosler Reloading Guide, Fifth Edition. Bend, Oregon: Nosler, Inc., 2002.

- Ramage, Ken, ed., Handloader's Digest, 18th Edition. Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2002. ISBN 087349475X

- Speer Reloading Manual, Number 14. Lewiston, Idaho: Speer, Inc., 2007.

See also

- Category:Ammunition

- List of rifle cartridges

- List of handgun cartridges

- Table of pistol and rifle cartridges by year

- List of Shotgun cartridges

- Firearm

- Cartridge

- Percussion cap

- Weapon

- Ammunition

- Terminal ballistics, External ballistics

- Casting

- Sabot

- Tracer ammunition

- Bullet bow shockwave

- Bullet Physics Engine

- Meplat

External links

- European Ammunition Box Translations

- Dangerous Game Bullets.

- Bullet acronyms and abbreviations with illustrations

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.