Boxer Rebellion

| Boxer Rebellion | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

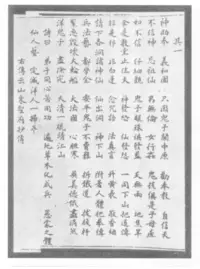

Boxer forces (1900 photograph). | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||

| Eight-Nation Alliance | Righteous Harmony Society | ||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Edward Seymour Alfred Gaselee |

Ci Xi | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 20,000 | Over 100,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||

| 230 foreigners, thousands of civilians | Unknown | ||||||||

- This article is about The Boxer Rebellion Uprising. For the Boxer society, see Righteous Harmony Society. For the band, see The Boxer Rebellion (band).

The Boxer Uprising (Traditional Chinese: 義和團起義; Simplified Chinese: 义和团起义; pinyin: Yìhétuán Qǐyì; literally "The Righteous and Harmonious Fists") or Boxer Rebellion (義和團之亂 or 義和團匪亂) was a Chinese rebellion against foreign influence in areas such as trade, politics, religion and technology that occurred in China during the final years of the Qing Dynasty from November 1899 to September 7, 1901[1]. By August 1900, over 230 foreigners, tens of thousands of Chinese Christians, an unknown number of rebels, their sympathizers and other innocent bystanders were killed in the ensuing chaos. The brutal uprising crumbled on August 4, 1900 when 20,000 foreign troops entered the Chinese capital, Peking (Beijing).(pg 232. The search for Modern China, Spence)

Anti-Foreign movement

In 1839, the First Opium War broke out, and China was defeated by Britain. In view of the weakness of the Qing government, Britain and other nations such as France, Russia and Japan started to exert influence over China. Due to their inferior army and navy, the Qing Dynasty was forced to sign many agreements which became known as the "Unequal Treaties". These include the Treaty of Nanking (1842), the Treaty of Aigun (1858), the Treaty of Tientsin (1858), the Convention of Peking (1860), the Treaty of Shimonoseki (1895), and the Second Convention of Peking (1898).

Such treaties were regarded as grossly unfair by many Chinese. They had always considered themselves to be superior to foreigners, but their prestige was sorely damaged by the treaties, as foreigners were perceived to receive special treatment compared to Chinese. Rumours circulated of foreigners committing crimes as a result of agreements between foreign and the Chinese governments over how foreigners in China should be prosecuted. In Guizhou, local officials were reportedly shocked to see a cardinal using a sedan chair decorated in the same manner as one reserved for the governor. The Catholic Church's prohibition on some Chinese rituals and traditions were another issue of contention. Thus in the late 19th century such feelings increasingly resulted in civil disobedience and violence towards both foreigners and Chinese Christians.

The rebellion was initiated by a society known as the Righteous Harmony Society (義和拳) or in contemporary English parlance, "Boxers", a group which initially opposed, but later reconciled itself, to China's ruling Manchu Qing Dynasty. The Boxer rebellion was concentrated in northern China where the European powers had begun to demand territorial, rail and mining concessions. Imperial Germany responded to the killing of two missionaries in Shandong province in November 1897 by seizing the port of Qingdao. A month later, a Russian naval squadron took possession of Lushun, in southern Liaoning. Britain and France followed, taking possession of Weihai and Zhanjiang respectively.

The Rebellion

Boxer activity developed in Shandong province in March 1898, in response to both foreign influence in the region and the failure of the Imperial court's "self-strengthening" strategy of officially-directed development, whose shortcomings had been shown graphically by China's defeat in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). One of the first signs of unrest appeared in a small village in Shandong province, where there had been a long dispute over the property rights of a temple between locals and the Catholic authorities. The Catholics claimed that the temple was originally a church abandoned decades previously after the Kangxi Emperor banned Christianity in China. The local court ruled in a favor of the Church, angering the villagers who claimed they needed the temple for various rituals and had traditionally used it to practice martial arts. After the local authorities seized the temple and gave it to the Catholics, villagers attacked the church under the leadership of the Boxers.

The early months of the movement's growth coincided with the Hundred Days' Reform (June 11–September 21, 1898), during which the Guangxu Emperor of China sought to improve the central administration, before the process was reversed at the behest of his powerful aunt, the Empress Dowager Cixi. After a mauling at the hands of loyal Imperial troops in October 1898, the Boxers dropped their anti-government slogans, turning their attention to foreign missionaries (such as Hudson Taylor) and their converts, whom they saw as agents of foreign imperialist influence. The Empress Dowager Cixi, who credited the Boxers' claim of magical imperviousness to both blade and bullet, decided to use the Boxers to remove the foreign powers from China. The Imperial Court, now under Cixi's firm control, issued edicts in defence of the Boxers, drawing heated complaints from foreign diplomats in January, 1900.

The conflict came to a head in June, 1900, when the Boxers, now joined by elements of the Imperial army, attacked foreign compounds within the cities of Tianjin and Peking. The legations of the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, Russia and Japan were all located on the same city block close to the Forbidden City, built there so that Chinese officials could keep an eye on the ministers - the legations themselves were strong structures surrounded by walls. The legations were hurriedly linked into a fortified compound and became a refuge for foreign citizens in Peking. However the Spanish, Belgian, and German legations were not in the same compound. Although the Spanish and Belgian legations were only a few streets away and their staff were able to arrive safely at the compound, the German legation was on the other side of the city and was stormed before the staff could escape. When the Envoy for the German Empire, Klemens Freiherr von Ketteler, was kidnapped and killed on June 20, the foreign powers declared open war against China. The Chinese Court in turn proclaimed hostilities against those nations, who began to prepare military forces to relieve the besieged embassies. In Peking, the fortified legation compound remained under siege from Boxer forces from June 20 to August 14. Under the command of the British minister to China, Claude Maxwell MacDonald, the legation staff and security personnel defended the compound with one old muzzle-loaded cannon (it was nicknamed the "International Gun" because the barrel was British, the carriage was Italian, the shells were Russian, and the crew was American) and small arms.

Stories appeared in the foreign media describing the fighting going on in Peking. Some were mere rumour or exaggerated the nature of the conflict, but others more accurately described the torture and murder of captured foreigners. Chinese Christians suffered even more greatly, as there were more of them and most were not able to seek refuge in the legations, having to seek shelter elsewhere. Those that were caught were raped as well as tortured and murdered. As a result of these reports, a great deal of anti-Chinese sentiment was generated in Europe, America, and Japan.

Despite their efforts, the Boxer rebels were unable to break into the compound, which was relieved by the international army of the Eight-Nation Alliance in July.

Eight-Nation Alliance

First intervention

Foreign navies started to build up their presence along the northern China coast from the end of April 1900. Upon the request of foreign embassies in Beijing 750 troops, from five countries, were dispatched to the capital on May 31.

As the situation worsened, a second International force of 2,000 marines under the command of the British Vice Admiral Edward Seymour, the largest contingent being British, was dispatched from Tianjin to Beijing on June 10th. They met however with stiff resistance from Chinese governmental troops. They were finally rescued by allied troops from Tianjin, where they retreated back on June 26, with the loss of 350 men.

Second intervention

Template:Boxer Rebellion With a difficult military situation in Tianjin, and a total breakdown of communications between Tianjin and Beijing, the allied nations took steps to reinforce their military presence dramatically. On June 17th, they took the Taku Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and from there brought more and more troops on shore.

The international force, with British Lt-General Alfred Gaselee acting as the commanding officer, called the Eight-Nation Alliance, eventually numbered 54,000, with the main contingent being composed of Japanese soldiers: Japanese (20,840), Russian (13,150), British (12,020), French (3,520), American (3,420), German (900), Italian (80), Austro-Hungarian (75), and anti-Boxer Chinese troops.

The international force finally captured Tianjin on July 14 under the command of the Japanese colonel Kuriya, after one day of fighting.

Notable exploits during the campaign were the seizure of the Taku Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and the boarding and capture of four Chinese destroyers by Roger Keyes.

In general, the march, about 120 km, from Tianjin to Beijing by the allies, on August 4, was not particularly harsh despite approximately 70,000 Imperial troops and anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 Boxers along the way. They only encountered minor resistance and a battle was engaged in Yangcun, about 30 km outside Tianjin, where the 14th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. and British troops led the assault. However, the weather was a major obstacle, extremely humid with temperatures sometimes reaching 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 Celsius).

The International force reached and occupied Beijing on August 14.

The United States was able to play a secondary, but significant, role in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion because of the large number of American ships and troops deployed in the Philippines as a result of the U.S. conquest of the islands during the Spanish American War (1898) and the subsequent Philippine-American War. In the United States military, the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion was known as the China Relief Expedition.

Aftermath

Troops from most nations (bar American and Japanese troops) engaged in plunder, looting and rape. German troops in particular were criticized for their enthusiasm in carrying out Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany's July 27 order to "make the name German remembered in China for a thousand years so that no Chinaman will ever again dare to even squint at a German". This speech, in which Wilhelm invoked the memory of the 5th century Huns, gave rise to the British derogatory name "Hun" for their German enemy during World War I.

On September 7, 1901, the Qing court was compelled to sign the "Boxer Protocol", also known as Peace Agreement between the Eight-Nation Alliance and China, undertaking to execute ten officials linked to the outbreak and to pay war reparations of $333 million. Much of it was later earmarked by both Britain and the U.S. for the education of Chinese students at overseas institutions, subsequently forming the basis of Tsinghua University. The British signatory of the Protocol was Sir Ernest Satow.

The court's humiliating failure to defend China against the foreign powers contributed to the growth of republican feeling, which was to culminate a decade later in the dynasty's overthrow and the establishment of the Republic of China.

The foreign privileges which had angered Chinese people were largely cancelled in the 1930s and 1940s.

Russia had meanwhile been busy (October 1900) with occupying much of the north-eastern province of Manchuria, a move which threatened Anglo-American hopes of maintaining what remained of China's territorial integrity and openness to commerce (the "Open Door Policy") to all comers, but paid the concept only lip service. This behavior led ultimately to a disastrous Russian defeat (conflict) at the hands of an increasingly confident Japan (1904-1905), as they maintained garrisons and improved fortifications between Port Arthur and Harbin along the southern spur line of the Manchurian Railway constructed on their leased lands.

Results

During the incident, 48 Catholic missionaries and 18,000 members were killed, along with 182 Protestant missionaries and 500 Chinese Christians.

The effect on China was a weakening of the dynasty, although it was temporarily sustained by the Europeans who were under the impression that the Boxer Rebellion was anti-Qing. China was also forced to pay almost $333 million in reparations. China's defenses were weakened, and the aunt (Dowager Cixi) of the reigning Guangxu Emperor, who was the actual person in command of the country at that time, realized that in order to survive, China would have to reform, despite her previous opposition. Among the Imperial powers, Japan gained prestige due to its military aid in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion and was first seen as a power. Its clash with Russia over the Liaodong and other provinces in eastern Manchurian, long considered by the Japanese as part of their sphere of influence led to the Russo-Japanese War when two years of negotiations broke down in February 1904. Germany, as mentioned above, earned itself the nickname "Hun" and occupied Qingdao bay, consequently fortifying to serve as Germany's primary naval base in East Asia. The Russian Lease of the Liaodong (1898) was confirmed. The American U.S. 9th Infantry Regiment earned the nickname "Manchus" for its actions during this campaign. Current members of the regiment (stationed in Camp Casey, South Korea) still do a commemorative 25-mile (40 km) footmarch every quarter in remembrance of the brutal fighting. Soldiers who complete this march are authorized to wear a special belt buckle that features a Chinese imperial dragon on their uniforms.

Controversy in modern China

Though the reaction of the Boxers against foreign imperialism in China is regarded by some as patriotic, the violence that they caused in committing acts of murder, robbery, vandalism and arson cannot be considered much different from the events of other rebellions in China, if not worse. Some people in China consider this movement as a rebellion (亂; disorder; Mandarin Pinyin: luàn), a negative term in Chinese language, when described by commentators during the years of the Qing dynasty and Republic of China. However, Chinese Communists have shifted the perception of the rebellion by referring to it as an uprising (起義; being upright; qǐyì), a more positive term in the Chinese language. It is frequently referred to as a "patriotic movement" in the People's Republic of China by Communist politicians.

In January 2006, Freezing Point, a weekly supplement to the China Youth Daily newspaper, was closed partly due to its running of an essay by Yuan Weishi (History professor at Zhongshan University) that criticised the way in which the Boxer Rebellion and 19th century history about foreign interaction with China was portrayed in Chinese textbooks and taught at school. [1]

Nevertheless, Chinese people used to be very sensitive towards the history of foreign imperialism in the late 19th and the early 20th century. The kind of anti-foreignism still persists under the surface. It may be due to this, together with the view imposed by the Chinese Government, that many Chinese people do not regard this as a rebellion.

In fiction

The events were made into the 1963 film, 55 Days at Peking. The film, which was shot in Spain, needed thousands of Chinese extras, and the company sent scouts throughout Spain to hire as many as they could find. The result was that many Chinese restaurants in Spain closed for the duration of the filming because the restaurant staff—often the restaurant's owners—were hired away by the film company. The company hired so many that for several months there was scarcely a Chinese restaurant to be found open in the entire country.[2]

In 1975, Hong Kong's Shaw Brothers studio made a movie, titled Pa kuo lien chun, of the events, giving director Chang Cheh one of the highest budgets up to that time to tell a sweeping story of disillusionment and revenge. [2] It depicts followers of the Boxer clan being duped into believing they were impervious to attacks by firearms. The fight sequences were choreographed by Liu Chia-Liang (Lau Kar Leung) and it starred Alexander Fu Sheng as well as Wang Lung-Wei.

In the 1995 postcyberpunk novel, The Diamond Age, by Neal Stephenson, the Boxer Rebellion is vaguely retold in a 2100s Shanghai setting.

In the television series, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, it was during the Boxer rebellion that the vampire Spike killed his first slayer - a young Chinese woman named Xin Rong.

The popular film series, Once Upon a Time in China, starring Jet Li as the legendary martial artist/Chinese doctor Wong Fei Hung, conveys the ambiance and tumult of this time period with many historic events woven into the plotlines.

In the movie, Shanghai Knights, the Boxers, led by Wu Chow and backed by British Lord Nelson Rathbone, killed Chon Wang and Chon Lin's father, attempt to assassinate Queen Victoria, unite the Emperor's enemies and storm the Forbidden City in order for their leaders to become King of the United Kingdom and Emperor of China, but they fail.

The novel, Moment In Peking, by Lin Yutang, opens during the Boxer Rebellion, and provides a child's-eye view of the turmoil through the eyes of the protagonist.

The novel, Los Impostores (The Impostors), by Colombian fiction author Santiago Gamboa, deals with a modern day Boxer sect and its members' efforts to recover a sacred Boxer text held by Catholic priests in China.

See also

- Nieh Shih-ch'eng

- Opium Wars

- Shiba Goro

- Auguste Chapdelaine

- Great Wall of China hoax

External links

- 55 Days at Peking at the Internet Movie Database

- Pa kuo lien chun at the Internet Movie Database

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Boxer Rebellion (Third China War) 1900

- ↑ 55 Days at Peking at the Internet Movie Database

- The Boxer Rebellion by Diana Preston, Berkley Books, New York, 2000 ISBN 0-425-18084-0

- Dragon Lady: The Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China by Sterling Seagrave, Vintage Books, New York, 1992 ISBN 0-679-73369-8 This book challenges the notion that the Empress-Dowager used the Boxers. She is portrayed sympathetically.

- The dragon empress : life and times of Tz'u-hsi 1835-1908 : empress dowager of China by Marina Warner, Vintage, UK, US 1993, ISBN 0099165910

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.