Difference between revisions of "Bohemia" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

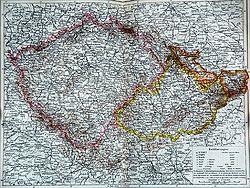

[[Image:Czechoslovakia01.png|thumb|right|250px|Bohemia within Czechoslovakia in 1928]] | [[Image:Czechoslovakia01.png|thumb|right|250px|Bohemia within Czechoslovakia in 1928]] | ||

| − | After [[World War I]], Bohemia became the core of the newly-formed country of [[Czechoslovakia]], which combined Bohemia, | + | After [[World War I]], Bohemia declared independence and on October 28, 1918, became the core of the newly-formed country of [[Czechoslovakia]], which combined Bohemia, Moravia, Austrian [[Silesia]], and Slovakia. Under its first president, [[Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk]], Czechoslovakia became a prosperous liberal democratic republic. |

| − | Following the [[Munich Agreement]] | + | Following the [[Munich Agreement]] of 1938, the Sudetenland, the border regions of Bohemia inhabited predominantly by ethnic Germans, were annexed by Nazi [[Germany]]; this was the first and only time in Bohemia’s history that its territory was divided. The remnants of Bohemia and Moravia were then annexed by Germany in 1939, while the Slovak portion became [[Slovakia]]. Between 1939 and 1945, Bohemia, excluding the Sudetenland, formed, along with Moravia, the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (''Reichsprotektorat Böhmen und Mähren''). After the end of [[World War II]] in 1945, a vast majority of ethnic German population was expelled from the country based on the [[Eduard Beneš]] decrees. This act continues to torment the Czech consciensce and remains subject of endless debates. |

[[Image:CZ-cleneni-Cechy-wl.png|thumb|right|250px|Bohemia within the Czech Republic today ''(in green)'']] | [[Image:CZ-cleneni-Cechy-wl.png|thumb|right|250px|Bohemia within the Czech Republic today ''(in green)'']] | ||

| − | Beginning in 1949, Bohemia ceased to be an administrative unit of Czechoslovakia, | + | On February 25, 1948, [[Communism|Communist]] ideologues won over Czechoslovakia and cast the country into 40 years of dictatorship. Beginning in 1949, the country was divided into districts and Bohemia ceased to be an administrative unit of Czechoslovakia. In 1989, [[Pope John Paul II]] canonized Agnes of Bohemia as the first saint in Central Europe, just before the events of the Velvet Revolution put an end to the one-party system in November of that year. When Czechoslovakia was dissolved amicably in 1993 in the Velvet Divorce, the territory of Bohemia became part of the newly emerged [[Czech Republic]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The Czech constitution from 1992 refers to the "citizens of the Czech Republic in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia" and proclaims continuity with the statehood of the Bohemian Crown. Bohemia is not an administrative unit of the Czech Republic; instead, it is divided into the [[Prague]], Central Bohemian, Plzeň, Karlovy Vary, Ústí nad Labem, Liberec, and Hradec Králové Regions, as well as parts of the Pardubice, Vysočina, South Bohemian, and South Moravian Regions. | ||

==Footnotes== | ==Footnotes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | == | + | ==References and Further Reading== |

| − | * Sayer,Derek , ''The coasts of Bohemia: a Czech history'', Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1998, ISBN 0691057605 - ISBN 9780691057606 | + | * Sayer, Derek , ''The coasts of Bohemia: a Czech history'', Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1998, ISBN 0691057605 - ISBN 9780691057606. |

| − | * Freeling,Nicolas , ''The Seacoast of Bohemia'', New York, Mysterious Press, 1995, ISBN 089296555X - ISBN 9780892965557 OCLC: 31754195 | + | * Freeling, Nicolas , ''The Seacoast of Bohemia'', New York, Mysterious Press, 1995, ISBN 089296555X - ISBN 9780892965557 OCLC: 31754195. |

| − | * Teich, Mikuláš, ''Bohemia in History'', Cambridge, U.K.; New York, NY, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0521431557 OCLC: 37211187 | + | * Teich, Mikuláš, ''Bohemia in History'', Cambridge, U.K.; New York, NY, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0521431557 OCLC: 37211187. |

| − | * Oman, Carola, ''The Winter Queen: Elizabeth of Bohemia'', London; Phoenix, 2000, ISBN 1842120573 OCLC: 43879234 | + | * Oman, Carola, ''The Winter Queen: Elizabeth of Bohemia'', London; Phoenix, 2000, ISBN 1842120573 OCLC: 43879234. |

| + | * Kann, Robert A. ''A History of the Habsburg Empire: 1526–1918''. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1974. ISBN 0-520-02408-7. | ||

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

| − | http://www.vol.cz/RUDOLFII/umelcien.html | + | * [http://www.vol.cz/RUDOLFII/umelcien.html “Rudolf II and his Artists”] |

| − | Jacob | + | * Wisse, Jacob [http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rupr/hd_rupr.htm] |

* [http://www.czech.cz/en/culture/regions-attractivity-and-diversity/bohemia/ Bohemia] | * [http://www.czech.cz/en/culture/regions-attractivity-and-diversity/bohemia/ Bohemia] | ||

| − | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_IV,_Holy_Roman_Emperor | + | * [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_IV,_Holy_Roman_Emperor |

| − | http://www.sweb.cz/royal-history/premysl.html | + | * [http://www.sweb.cz/royal-history/premysl.html |

| − | http://dejepis.info/?t=94 | + | * [http://dejepis.info/?t=94 “Late PremyslidsVrcholní Přemyslovci na českém trůně, královský titul jako dědičný, vrcholné období středověkých českých dějin |

| − | http://www.oa.svitavy.cz/pro/renata/dejiny/z8109/preot.htm | + | * [http://www.oa.svitavy.cz/pro/renata/dejiny/z8109/preot.htm “Premysl I. Otakar”] |

| − | http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=slavnik&dir=premyslovci&menu=premyslovci | + | * [http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=slavnik&dir=premyslovci&menu=premyslovci “Boleslav II and the Slavniks] |

historie ceske republiky | historie ceske republiky | ||

| − | http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=povesti&dir=povesti&menu=povesti | + | * [http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=povesti&dir=povesti&menu=povesti |

| − | http://zivotopisyonline.cz/svaty-vaclav.php | + | * [http://zivotopisyonline.cz/svaty-vaclav.php “St. Wenceslas"Světec a patron českých zemí" |

| − | + | ”] Biographies Online, | |

| − | + | * http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=lucemburk&dir=lucemburk&menu=lucemburk Lucemburkové na českém trůnu | |

| − | "Světec a patron českých zemí" | + | * http://zivotopisyonline.cz/jan-lucembursky-slepy.php Jan Lucemburský Slepý |

| − | http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=lucemburk&dir=lucemburk&menu=lucemburk Lucemburkové na českém trůnu | ||

| − | http://zivotopisyonline.cz/jan-lucembursky-slepy.php Jan Lucemburský Slepý | ||

(10.8.1296 - 26.8. 1346) | (10.8.1296 - 26.8. 1346) | ||

"Otec Karla IV." | "Otec Karla IV." | ||

| − | http://zivotopisyonline.cz/karel-ctvrty-lucembursky.php Karel IV. Lucemburský | + | * http://zivotopisyonline.cz/karel-ctvrty-lucembursky.php Karel IV. Lucemburský |

(14.5.1316-29.11.1378) | (14.5.1316-29.11.1378) | ||

"Otec vlasti" | "Otec vlasti" | ||

| − | http://zivotopisyonline.cz/zikmund-lucembursky.php Zikmund Lucemburský | + | * http://zivotopisyonline.cz/zikmund-lucembursky.php Zikmund Lucemburský |

(14.2.1368-9.12.1437) | (14.2.1368-9.12.1437) | ||

"Liška ryšavá?" | "Liška ryšavá?" | ||

| − | http://www.hotelpraguecity.com/fotky/okoli/zizka2.html Jan Zizka: The Blind General | + | * http://www.hotelpraguecity.com/fotky/okoli/zizka2.html Jan Zizka: The Blind General |

| − | http://www.radio.cz/en/article/37448 Jan Zizka | + | * http://www.radio.cz/en/article/37448 Jan Zizka |

[23-02-2000] By Nick Carey | [23-02-2000] By Nick Carey | ||

| − | http://www.husitstvi.cz/husitske-valecnictvi.php | + | * http://www.husitstvi.cz/husitske-valecnictvi.php |

| − | http://www.husitstvi.cz/ro2.php Jan Žižka z Trocnova (z Kalicha) | + | * http://www.husitstvi.cz/ro2.php Jan Žižka z Trocnova (z Kalicha) |

| − | http://www.answers.com/topic/rudolf-ii-holy-roman-emperor | + | * http://www.answers.com/topic/rudolf-ii-holy-roman-emperor |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 03:17, 23 April 2007

Bohemia (Czech: Čechy; Template:Audio-de) is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western and middle thirds of the Czech Republic. It has an area of 52,750 km² and 6.25 million of the country's 10.3 million inhabitants.

Bohemia is bordered by Germany to the southwest, west, and northwest, Poland to the north-east, the Czech historical region of Moravia to the east, and Austria to the south. Bohemia's borders are marked with mountain ranges such as the Šumava, the Ore Mountains, and the Giant Mountains within the Sudeten mountains.

Note: In the Czech language there is no distinction between adjectives referring to Bohemia and the Czech Republic, i.e. český means both Bohemian and Czech.

pict of zizka, charles IV, Rudolf II, Hussite weaponsj, St. Wenceslas etc.

History

Ancient Bohemia

The first unequivocal reference to Bohemia dates back to the Roman times, with names such as Boiohaemum, Germanic for "the home of the Boii," a Celtic people. Lying on the crossroads of major Germanic and Slavic tribes during the Migration Period, the area was settled from about 100 B.C.E. by Germanic peoples, including the Marcomanni, who then moved southwest and were replaced around 600 C.E. by the Slavic precursors of today's Czechs.

Přemyslid dynasty

After freeing themselves from the rule of the Avars in the 7th century, Bohemia's Slavic inhabitants came in the 9th century under the rule of the Premyslids, the first historically proven dynasty of Bohemian princes, which lasted until 1306. A legend says that the first Premyslid prince was Premysl Orac, who married Libuse, the founder of Prague, but the first historically documented prince was Borivoj I. The first Premyslid to use the title of King of Bohemia was Boleslav I, after 940, but his successors again assumed the title of duke. The title of king was then granted to Premyslid dukes Vratislav II and Vladislav II in the 11th and 12th centuries, respectively, and became hereditary under Ottokar I in 1198.

With Bohemia's conversion to Christianity in the 9th century, close relations were forged with the East Frankish kingdom, then part of the Carolingian empire and later the nucleus of the Holy Roman Empire, of which Bohemia was an autonomous part from the 10th century on. Under Boleslav II “Pious”, the Premyslid dynasty strengthened its position by founding a bishopric in Prague in 973, thus severing the dependence of the Czech Church on the German Church and opening up the territory for German and Jewish merchant settlements.

At the same time, the powerful House of Slavniks were working to establish a separate duchy in the eastern part of Bohemia – backed by an army and fortresses, and they went on to gain control over more than one-third of Bohemia. In 982, Vojtech of the Slavnik dynasty was appointed Prague bishop and sought separation of the Church and state. His brothers maintained ties with the German ruler and minted their own currency. The Czech lands thus saw concurrent development of two independent states – the of the Premyslids and Slavniks. Boleslav II did not tolerate competition for long and in 995 had all Slavniks murdered, an act that marked the unification of Czech lands.

Ottokar I’s assumption of the throne in 1197 marked the culmination of the Premyslid dynasty and the rule of Bohemia by hereditary kings. In 1212, Roman king Friedrich II affirmed the status of Bohemia as kingdom internationally in a document called the Golden Bula of Sicily. This gave the king a privilege to name bishops and extricated the Czech lands from dependence on Roman rulers. Ottokar I’s grandson Ottokar II, who ruled in 1253–1278, founded a short-lived empire that covered modern Austria.

A crucial event in the history of Czech statehood from the second half of the 11th century proved to be the murder of St. Wenceslav (sv. Václav) and his subsequent status as the prince from heaven and protector of the Czech state, whereas Czech rulers were relegated to the status of its temporary representatives. The son of Premyslid duke Vratislav I, he was raised by his grandmother, Ludmila, and after she was murdered shortly after he inherited the rule, he repudiated his mother Drahomira. Wenceslas facilitated the development of the Church and forged ties with Saxony, away from Bavaria, much to the dislike of his political opposition headed by his younger brother Boleslav I “Terrible”. This brotherly conflict ended in murder, when Boleslav I had his brother murdered in 935 on the occasion of the consecration of a church and took over the reign of the Czech lands. Wenceslas was worshipped as a saint from the 10th century, first in the Czech lands and later in neighboring countries. His life and martyrdom were written into numerous legends, including the “First Old Slavonic Legend” that originated in the 10th century.

The mid-13th century saw the beginning of substantial German immigration as the court sought to replace losses from the brief Mongol invasion of Europe in 1241. The Germans settled primarily along the northern, western, and southern borders of Bohemia, although many lived in towns throughout the kingdom.

Luxembourg dynasty

John

The death of the last Premyslid duke, Wenceslas III (Václav III), sent the Czech dukes to a period of hesitation as to the choice of the Czech king, until they selected John of Luxembourg “Blind”, the son of Friedrich VII, the king of Germany and Roman Empire, in 1310, with condititions, including extensive concessions to the Czech dukes. John married the sister of the last Premyslid but the Czech kingdom was an unexplored territory for him; he did not understand the customs or needs of the country. He ruled as the King of Bohemia in 1310-1346 and the King of Poland in 1310-1335. Being a shrewd politician nicknamed “King Diplomat”, John annexed Upper Silesia and most Silesian duchies to Bohemia, and had his sights set at northern Italy as well. In 1335, he gave up all claims to the Polish throne.

Charles IV

In 1334, John appointed his oldest son Charles IV as the de facto administrator of Czech lands, setting off the period of Luxembourg dual reign, and six years later he safeguarded the Czech crown for him as well as Charles’ endeavors to obtain the Roman kingship, in which Charles succeeded in 1346, still during his father’s life. Charles IV was crowned as the King of Bohemia in 1346 and labored to uplift not only Bohemia but also the rest of Europe. As the Holy Roman Emperor and the Czech king, dubbed the “Father of the Country”, he is the most notable European ruler of the late Middle Ages. In line with the Luxembourg tradition, Charles IV was sent at a very young age to the French court, where he received extensive education and acquired mastery of German, French, Latin, and Italian languages. Czech language was the closest to his heart though, and two years into his election as king, he founded central Europe's first university, Charles University in Prague.

In 1355, Charles IV ascended to the Roman throne, and a year later he issued the Golden bula of Charles IV, a set of statutes to be valid in the Holy Roman Empire until 1806. His reign brought Bohemia to its peak both in terms of policy and territory; the Bohemian crown controlled such diverse lands as Moravia, Silesia, Upper Lusatia and Lower Lusatia, Brandenburg, an area around Nuremberg called New Bohemia, Luxembourg, and several small towns scattered around Germany. On the home turf, he triggered an unprecedented economic, cultural and artistic boom in Prague and the rest of Bohemia. On the home turf, he triggered an unprecedented economic, cultural and artistic boom in Bohemia, refusing to move to Rome and instituting Prague as the imperial capital. Construction in Prague was in the full swing, and many sights bear his name. The Prague Castle and much of the Saint Vitus Cathedral were completed under his patronage. The Czech Republic labels him Father of the Country (Pater patriae in Latin), a title first coined at his funeral. His imperial policy was focused on the economic and intellectual development of Bohemia; he corresponded with Petrarch, the initiator of Renaissance Humanism, who hoped in vain that Charles IV would transfer the capital of the Holy Roman Empire from Prague to Rome and renew the glory of the Empire.

Sigismund

Charles IV’s son Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg, the last of the House of Luxembourg on the Czech throne, as well as the King of Hungary and Holy Roman Emperor, has left behind a legacy of contradictions. He lost the Polish crown in 1384 but gained the Hungarian crown in 1387. In an effort to secure the Dalmatian coast under his reign, he organized a crusade but was defeated by the Osman Turks. After internment by the Hungarian nobility in 1401, he refocused his efforts on Bohemia and lent his support to the higher nobility fighting his step-brother, King Wenceslas IV, whom he later took hostage and transferred to Vienna for over a year. As an administrator of the Czech Kingdom appointed by Wenceslas IV, he took over the Czech crown. After the brothers’ reconciliation in 1404, Sigismund returned to Hungary, where he calmed down political turbulences and initiated an economic and cultural boom, granting privileges to cities, which he considered as the cornerstone of his rule. He also considered the Church subordinate to secular rule, and in 1403-1404, after disputes with the pope, he banned monetary appropriations for the Church and manned bishoprics and other religious institutions.

As a Roman king, Sigismund sought to reform the Roman Church and settle the papal schism, a token of which was the convening of the Council of Constance in 1415, the rector of Charles University and a prominent reformer and religious thinker Jan Hus was sentenced to be burned at the stake as a heretic, with the king’s undeniable involvement. Hus was invited to attend the council to defend himself and the Czech positions in the religious court, but with the emperor's approval, he was executed on July 6, 1415. His execution of Hus, as well as a papal crusade against the Hussites and John Wycliffe, outraged the Czechs. Their ensuing rebellion against Romanists became known as the Hussite Wars.

Although a natural successor to Wenceslas IV, as a Czech king, Sigismund, who inherited the Czech throne in 1420, grappled with defiance from the Hussites, whom he unsuccessfully sought to subdue in repeated crusades. Only in 1436, after he agreed to reconciliatory terms between the Hussites and the Catholic Church, was he recognized as the Czech king. One year later he died.

Hussite Bohemia

You who are the warriors of God and His law. Ask God for help and hope in Him that in His name you may gloriously triumph. http://www.husitstvi.cz/archiv/Chor%E1l%20Kto%9E%20js%FA%20bo%9E%ED%20bojovn%EDci%20(sample).mp3

(Hussite battle hymn)

The Hussite Wars, which started in 1419, sent people flocking to Prague plundering monasteries and other symbols of the corrupt Catholic Church, but it was under Zizka, who authored the best defense strategy for the largely peasant Hussites, that the wars against Sigismund’s crusades started to gain momentum. He moved to South Bohemia, where he helped found the stronghold of Tabor. Žižka, born into a family of lower nobility, joined in an armed gang formed by members of his class to rob merchants and took part in minor conflicts among wealthy nobles. After he helped defeat Prussia's Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410 in Poland, he returned to Prague and joined the king's court at the time when Hus preached regularly in Prague’s Bethlehem Chapel, but it was never proved whether he attended any of them. With the outbreak of the Hussite Wars in 1419, an opportunity to hone his tactical genius came knocking.

The Hussite Wars split the general Hussite movement into various groups of moderates and radicals. The moderates, essentially in agreement with the Catholic Church, were called Utraquists and consisted of the lesser nobility and the bourgeoisie. The most radical division was the Taborites, named after their religious center and stronghold at Tabor, which was founded by Zizka. Upholding the doctrines of Wycliffe, this group consisted of peasants.

When the wars started, Zizka was approaching 60 and was blind in one eye. Soon after joining the Taborites, he transformed the town of Tabor into a fortress that was next to impossible to topple. In 1420, he led the Taborite troops in their startling victory over Sigismund, where the king lost despite assistance from Hungarian and German armies. Emboldened by the victory, Zizka’s armies spread over the countryside, storming monasteries and villages and defeating the crusaders although he had become completely blind by 1421.

Since he was commanding a largely peasant formation, Zizka came up with weapons to suit the skills of his warriors, such as iron-tipped flails and armored farm wagons, which were mounted with small howitzer type cannons and broke through enemy lines easily. The wagons were also used to transport the troops, and it can be said that they were the precursors of modern tank warfare. Another of his ingenious tactics was lining the bottom of a pond beside his forces with women's clothes, which resulted in the enemy cavalry’s horses being trapped in the clothes and becoming an easy prey to men. This made it possible for him to defeat the 30,000-strong army of crusaders that arrived in Prague from all over Europe. He even ordered horses shoed the wrong way round, to confuse enemy troops on the direction of his forces.

Another, if not more important, Hussite asset was their conviction that they were fighting for the right cause, and when they sang the battle hymn “You who are God’s Warriors”, the enemy would frequently turn back before the battle started. They followed a strict organization system and discipline, which could not be said of their enemies, comprising mercenaries from all over Europe that were merely after loot.

Nevertheless, his extreme religious views began to clash with those of the Taborites, who were radical in their views, so he left the city to form his own, more moderate, Hussite wing in East Bohemia in 1423 while at the same time retaining a close alliance with the Taborites. The greatest genius of battlefield in Bohemia’s history died suddenly of the plague in 1424, with virtually no possessions of his own, and was succeeded by Prokop the Great, under whose lead the Hussites continued to score victories for another ten years, to the sheer terror of Europe, until they were torn apart by internal rivalries at the Battle of Lipany in 1436. This was a direct consequence of their division into two main factions, the moderate Ultraquists and the radical Taborites and the reunification of the former with the Catholic Church. This prompted Sigismund to declare the famous "only the Bohemians could defeat the Bohemians."

Although the Hussite movement ultimately failed, it was the first attempt to undermine two strongholds of medieval society – feudalism and the Roman Catholic Church. It not only paved the way for the Protestant Reformation and the rise of modern nationalism but also brought about military innovations masterminded by Zizka. Despite the crushing defeat in 1436, the Ultraquists were still in the position to negotiate reconciliation between Catholics and Utraquists and thus safeguard freedom of religion, albeit short-lived, coined in the Basel Compacts the same year.

In 1458, George of Podebrady took over the Bohemian throne and set out to create a pan-European Christian League that would consolidate all of Europe into a Christian entity. He appointed Leo of Rozmital to win support of European courts, but this effort was stalled by his deteriorating relationship and thus the loss of leverage with the Pope.

Habsburg Monarchy

After the death of King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia in the Battle of Mohács in 1526, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria was elected the King of Bohemia, and the country became a constituent state of the Habsburg Monarchy, and between 1436 and 1620 it enjoyed religious freedom as one of the most liberal countries of the Christian world.

Rudolf II

Rudolf II king of Hungary and Bohemia, and Holy Roman Emperor (ruled 1576–1612), left behind a controversial legacy thanks to his political and religious policies, which led to his ouster as ruler by members of his own family and contributed to the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), one of the most destructive wars in European history. Labeled as "the greatest art patron in the world," Rudolf II elevated court patronage in post-Renaissance Europe to a new level. Prague, called Rudolfine Prague during his era, became one of the leading centers of the arts and sciences in Europe. He became a believer in and practitioner of the occult, promoting alchemy and the Kabbala, and invited leading European artists, architects, scientists, philosophers, and humanists to work for him. The astronomers Tycho Brahe, who was made Imperial Mathematician in 1599, and Johannes Kepler established observatories in the city.

The emperor commissioned redesign and expansion of the castle, the construction of a new town hall and archbishop's palace, and several new churches, although his greatest contribution to arts lies in painting, sculpture, and the decorative arts, including those by Paolo Veronese, Correggio, Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Rudolf esteemed foreign artists above all, as they gave international weight to his rule and satisfied his hunger for Italian and Dutch work, in particular. His unbridled passion for collecting is evidenced by one of the greatest art collections among European courts, which reflected the broader scientific and artistic interests of his court. He amassed not only antiques but also recent and contemporary art. His painters also doubled as dealers to purchase works of art from all over Europe. He visited his artists in their workshops and raised the status of the painters' guild to that of a liberal art. However, shortly after his death in 1612, his collections and court entourage were largely dispersed.

However, Rudolf also had a dark side to him, possessing an unstable personality and suffering physical and psychological upheavals, which prompted him to retreat to his castle in Prague and focus on the occult. Partly responsible for his internal torment was the increasingly divisive struggle between Catholics and Protestants and the threat posed by the Ottoman Empire, which made him move the capital of the Habsburg Monarchy from Vienna to Prague.

He was educated at the leading Roman Catholic center of power in Europe, the court of Philip II (ruled 1556–1598) of Spain, but by the time his father, Emperor Maximilian II, died, a majority of Habsburg subjects had converted to various sects of Protestantism, as had the estates in most of the Habsburg lands. He invited the Jesuits into his lands to help him reconvert Protestants, which stirred up resistance from the Protestant estates, and in 1606, the Estates of Hungary, Austria, and Moravia voted to recognize his brother, Matthias (ruled 1612–1619), as ruler. Rudolf responded with a concession – promising in 1609 the Bohemian estates religious toleration if they would retain him as sovereign. This did not satisfy the estates though, instead setting in motion a chain of events that would culminate in the Second Defenestration of Prague in 1618 and the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War during the reign of King Ferdinand II.

Ferdinand II adamantly oppressed Protestant rights in Bohemia; consequently, the Bohemian nobility elected Frederick V, a Protestant, to replace Ferdinand on the Bohemian throne. However, the Protestant intermezzo ended abruptly with Frederick's defeat in the Battle of White Mountain in 1620. Many Protestant noblemen were executed or driven into exile, their lands transferred to Catholic loyalists.

Czech Renaissance Movement

In 1749, Bohemia became more closely connected to the Habsburg Monarchy with an approval by the Bohemian Diet of an administrative reform that included the indivisibility of the Habsburg Empire and the centralization of rule. The Royal Bohemian Chancellery was thus merged with the Austrian Chancellery.

Until 1627, the German language was the second official language in the Czech lands. Both German and Latin were widely spoken among the ruling classes, although German became increasingly dominant, while Czech was spoken in much of the countryside. The development of the Czech language among educated classes was restricted after the Battle of the White Mountain, which improved only marginally during the Enlightement era, when the Czechs caught up with the development by first revising and then rebuilding the language within two generations. The first notable figure of the Czech Slavic renaissance was Josef Dobrovský (1753-1829), a Jesuit priest who authored grammar books and dictionaries and is considered the first Slavist. Josef Jungmann (1773-1847) went further by focusing on the compilation of a Czech-German dictionary and writing a history of Bohemian literature in Czech, efforts that earned the Czechs permission by the authorities to teach Czech in high schools, albeit not as a language of instruction.

Pavel Josef Šafařík, a Slovak by birth, was another outstanding Slavist of the Czech renaissance movement.

At the end of the 18th century, Czech national revivalist movement—Czech renaissance movement—in cooperation with part of the Bohemian aristocracy, launched a campaign for the restoration of the historic rights of the Czech Kingdom, whereby the Czech language was to replace German as the language of administration. The enlightened absolutism of Joseph II and Leopold II, who introduced minor language concessions, showed promise for the Czech movement, but many of these reforms were later rescinded. During the Revolutions of 1848, many Czech nationalists called for autonomy for Bohemia from Habsburg Austria. The Prague Slavic Congress, 1848 was a major event. Delegates from individual Slavic nations met to state their grievances, gain understanding of the issues of their neighbors, and draw up a plan for further action, both on the national and the international levels. Although it was followed by riots and martial law, its accomplishment lies in the drafting of the petition of Slavic demands providing a blueprint for equality among nations. The old Bohemian Diet, one of the last remnants of the independence, was dissolved, although the Czech language experienced rebirth as in the period of Romantic nationalism.

In 1861, a new elected Bohemian Diet was established. The renewal of the old Bohemian Crown (Kingdom of Bohemia, Margraviate of Moravia, and Duchy of Silesia) became the official political program of both Czech liberal politicians and the majority of Bohemian aristocracy ("state rights program"), while parties representing the German minority and a small part of the aristocracy proclaimed loyalty to the centralistic constitution. After the defeat of Austria in the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, Hungarian politicians achieved the Ausgleich (compromise) which created Austria-Hungary in 1867, ostensibly guaranteeing equality between the Austrian and Hungarian portions of the empire. An attempt of the Czechs to create a tripartite monarchy Austria-Hungary-Bohemia failed in 1871, but the "state rights program" remained the official platform of Czech political parties) until 1918.

Dissolution of the Empire

Emperor Karl I of Austria, who ruled from 1916 to 1918, was the last King of Bohemia and the last monarch of the Habsburg Dynasty, which started showing signs of decline already in the 19th century, when Emperor Francis Joseph (1848–1916) lost control of Italy and Prussia.

20th century

After World War I, Bohemia declared independence and on October 28, 1918, became the core of the newly-formed country of Czechoslovakia, which combined Bohemia, Moravia, Austrian Silesia, and Slovakia. Under its first president, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, Czechoslovakia became a prosperous liberal democratic republic.

Following the Munich Agreement of 1938, the Sudetenland, the border regions of Bohemia inhabited predominantly by ethnic Germans, were annexed by Nazi Germany; this was the first and only time in Bohemia’s history that its territory was divided. The remnants of Bohemia and Moravia were then annexed by Germany in 1939, while the Slovak portion became Slovakia. Between 1939 and 1945, Bohemia, excluding the Sudetenland, formed, along with Moravia, the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (Reichsprotektorat Böhmen und Mähren). After the end of World War II in 1945, a vast majority of ethnic German population was expelled from the country based on the Eduard Beneš decrees. This act continues to torment the Czech consciensce and remains subject of endless debates.

On February 25, 1948, Communist ideologues won over Czechoslovakia and cast the country into 40 years of dictatorship. Beginning in 1949, the country was divided into districts and Bohemia ceased to be an administrative unit of Czechoslovakia. In 1989, Pope John Paul II canonized Agnes of Bohemia as the first saint in Central Europe, just before the events of the Velvet Revolution put an end to the one-party system in November of that year. When Czechoslovakia was dissolved amicably in 1993 in the Velvet Divorce, the territory of Bohemia became part of the newly emerged Czech Republic.

The Czech constitution from 1992 refers to the "citizens of the Czech Republic in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia" and proclaims continuity with the statehood of the Bohemian Crown. Bohemia is not an administrative unit of the Czech Republic; instead, it is divided into the Prague, Central Bohemian, Plzeň, Karlovy Vary, Ústí nad Labem, Liberec, and Hradec Králové Regions, as well as parts of the Pardubice, Vysočina, South Bohemian, and South Moravian Regions.

Footnotes

References and Further Reading

- Sayer, Derek , The coasts of Bohemia: a Czech history, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1998, ISBN 0691057605 - ISBN 9780691057606.

- Freeling, Nicolas , The Seacoast of Bohemia, New York, Mysterious Press, 1995, ISBN 089296555X - ISBN 9780892965557 OCLC: 31754195.

- Teich, Mikuláš, Bohemia in History, Cambridge, U.K.; New York, NY, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0521431557 OCLC: 37211187.

- Oman, Carola, The Winter Queen: Elizabeth of Bohemia, London; Phoenix, 2000, ISBN 1842120573 OCLC: 43879234.

- Kann, Robert A. A History of the Habsburg Empire: 1526–1918. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1974. ISBN 0-520-02408-7.

External Links

- “Rudolf II and his Artists”

- Wisse, Jacob [1]

- Bohemia

- [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_IV,_Holy_Roman_Emperor

- [http://www.sweb.cz/royal-history/premysl.html

- [http://dejepis.info/?t=94 “Late PremyslidsVrcholní Přemyslovci na českém trůně, královský titul jako dědičný, vrcholné období středověkých českých dějin

- “Premysl I. Otakar”

- “Boleslav II and the Slavniks

historie ceske republiky

- [http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=povesti&dir=povesti&menu=povesti

- [http://zivotopisyonline.cz/svaty-vaclav.php “St. Wenceslas"Světec a patron českých zemí"

”] Biographies Online,

- http://cr.ic.cz/index.php?clanek=lucemburk&dir=lucemburk&menu=lucemburk Lucemburkové na českém trůnu

- http://zivotopisyonline.cz/jan-lucembursky-slepy.php Jan Lucemburský Slepý

(10.8.1296 - 26.8. 1346) "Otec Karla IV."

- http://zivotopisyonline.cz/karel-ctvrty-lucembursky.php Karel IV. Lucemburský

(14.5.1316-29.11.1378) "Otec vlasti"

- http://zivotopisyonline.cz/zikmund-lucembursky.php Zikmund Lucemburský

(14.2.1368-9.12.1437) "Liška ryšavá?"

- http://www.hotelpraguecity.com/fotky/okoli/zizka2.html Jan Zizka: The Blind General

- http://www.radio.cz/en/article/37448 Jan Zizka

[23-02-2000] By Nick Carey

- http://www.husitstvi.cz/husitske-valecnictvi.php

- http://www.husitstvi.cz/ro2.php Jan Žižka z Trocnova (z Kalicha)

- http://www.answers.com/topic/rudolf-ii-holy-roman-emperor

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.