Bodhidharma

Introduction

Bodhidharma (Sanskrit: बोधिधर्म Chinese 菩提達摩, Japanese ダルマ), was a legendary Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th-6th century C.E. and played a seminal role in the transmission of Zen Buddhism from India to China (where it is known as Chan). He is considered by followers of Zen Buddhism to be the twenty-eighth Patriarch in a lineage that is traced directly back to Gautama Buddha himself. He is also credited with founding the famous Shaolin school of Chinese martial arts and is known as a Tripitaka Dharma Master.

Though the details of his biography are ambigious, his life and teachings continue to be an inspiration to practitioners of Zen Buddhism today. His teachings pointed to a direct experience of Buddha-Nature rather than an intellectual understanding of it, and he is best known for his terse style that infuriated some (such as Emperor Liang), while leading others to enlightenment.

Biography

The major sources providing information about Bodhidharma's life conflict with regard to his origins, the chronology of his journey to China, his death, and other details. One proposed set of birth and death dates is c. 440–528 C.E.; another is c. 470–543 c.e.. The sources for biographical details are Yang Xuanzhi’s, Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang (547 C.E.), a biography written by one of his disciples, Tanlin, which is found in the Long Scroll of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices (6th century C.E.), Daoxuan’s Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks (645 C.E.), and the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (952 C.E.), written by two students of Hsüeh-feng I-ts'un. All accounts of his life are filled with mundane and mythical elements, making an historically accurate biography impossible. What is most significant is the meaning that the stories of his life hold for Zen Buddhists, and how they continue to influence the tradition today.

The most common account of his life begins with his birth in India during the fifth century to an upper-caste family (either a Brahmin or a Kshatrya), and left his high social status to pursue a life of renunciation and religious practice. He became a follower of the Mahayana school of Buddhism under the twenty-seventh Patriarch Prajnatara, from whom he received the mind-to-mind transmission of enlightenment that is a defining feature of the Zen tradition. With this permission to transmit the Dharma to others, he left India to reinvigorate Buddhism in China with his unique message:

“A special transmission, outside of the scriptures,

Not dependent on the written word.

Directly pointing at the mind,

Seeing one’s own true nature, and attaining enlightenment.”

Bodhidharma’s journey to China is said in the Japanese tradition to have taken three years by boat. His most famous encounter in China was with the Emperor Wu of Liang, who was a strong supporter of Buddhism. The Emperor asked him how much merit all of his donations to the building of temples, printing of scriptures, and supporting of the Sangha (Buddhist community) had accumulated for him, to which Bodhidharma replied “no merit at all”. The most common explanation of his answer is that because the Emperor was doing these deeds, not for the good of others, but for his own benefit (i.e. generating good karma), he was acting out of selfishness, and therefore receives no merit. This episode also elucidates perhaps the central theme of Zen practice: the almost exclusive value placed on zazen (sitting meditation) and the resulting self-realization.

The Emperor then asked Bodhidharma “what is the highest meaning of the holy truths?”, to which he replied “empty, without holiness”, a reference to the Mahayana doctrine of emptiness (shunyata). The Emperor, now exasperated, asks Bodhidharma “who are you?”. Bodhidharma enigmatically responds “I don’t know” (Cleary and Cleary, 1992, p. 1).

This confrontation with Emperor Wu is the paradigm of both the style of relationship between master and disciple in Zen, and its distinctive tradition of koans (this episode is the first koan in the Blue Cliff Record). The goal of the Mahayana path is bring about insight in followers of their inherent Buddha-nature. Bodhidharma’s distinctive style of achieving this goal of awakening was not a gentle one with which one could bargain for more time in bed. It was jarring and immediate, like a bucket of cold water.

After this short encounter, he was expelled from the court and traveled further north into China, crossing the Yangtze River on a reed. When he stopped at a Shaolin temple at Mt. Song but was refused entry, he is said to have sat in meditation outside the monastery facing its walls (or in a nearby cave in other accounts) for nine years. A popular legend recounts how during this period he fell asleep, and was so furious that he cut off his eyelids to avoid ever falling asleep again during his practice. He threw them behind him, where they sprouted into tea plants upon hitting the earth. The monks were so impressed with his dedication to his zazen that he was finally granted entry. Once inside, he was dismayed with how weak and tired the Shaolin monks had become from their studying and meditation without any physical labor. To rectify the situation, he is said to have instituted a set of exercises for the monks to promote their physical health. As a result, Bodhidharma is said to have created the foundation of many schools of Chinese martial arts.

During his period of “facing the wall”, Bodhidharma was approached by a man named Huike, who implored the master to take him on as his student. Despite Huike’s numerous requests, Bodhidharma continued to sit without a reply. In desperation, Huike cut off his own arm as a demonstration of his deep sincerity. Bodhidharma finally agreed to take him on as a student, and eventually would pass on the insignia of the Patriarchs to him: the Buddha’s begging bowl, his robes, and a copy of the Lankavatara Sutra.

The cause and age of his death are unclear. One story recounts how two teachers, jealous of his renown, tried to poison him on several occasions. After their sixth attempt, he decided that, having successfully spread his teaching to China, it was time for him to pass into parinirvana. He is said to have died soon after sitting in zazen.

Spiritual Teachings

Bodhidharma was not a prolific writer or philosopher like many founders of other Buddhist schools, so we can only assume from the available material that he held the philosophical views common to other Mahayana sects, particularly the Yogacaran tradition.

The story of Bodhidharma’s life reveals almost all of the central elements of his teachings: the emphasis on zazen, the style of presentation and interaction with students (often referred to as “dharma-dueling” and found in many koans), the lack of emphasis on scholarship and intellectual debate, and the importance of personal realization and mind-to-mind transmission from teacher to disciple. These distinctive features the Bodhidharma brought with him from India to China almost 1500 years ago still define Zen Buddhism today.

Tradition holds that Bodhidharma's principal text was the Lankavatara Sutra, a development of the Yogacara or "Mind-only" school of Buddhism established by the Gandharan half-brothers Asanga and Vasubandhu. He is described as a "master of the Lankavatara Sutra", and an early history of Zen in China is titled "Record of the Masters and Disciples of the Lankavatara Sutra" (Chin. Leng-ch'ieh shih-tzu chi). Some sources go so far as to credit Bodhidharma with being he first to introduce this sutra to China.

Another characteristic feature of Bodhidharma’s presentation of Buddhism was the emphasis he placed on physical well-being. He taught that keeping our bodies healthy increases our mental energy and prepares us for the rigors that serious meditation practice requires. Bodhidharma's mind-and-body approach to spiritual practice ultimately proved highly attractive to the Samurai class in Japan, who incorporated Zen into their way of life, following their encounter with the martial-arts-oriented Zen Rinzai School introduced to Japan by Eisai in the 12th century.

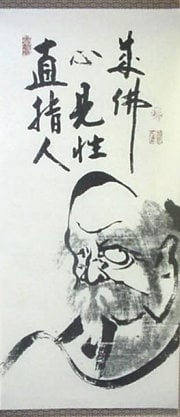

Portrayals of Bodhidharma

Throughout Buddhist art, Bodhidharma is depicted as a rather ill-tempered, profusely bearded and wide-eyed barbarian. He is described as "The Blue-Eyed Barbarian" in Chinese texts.

Chan texts also present Bodhidharma as the 28th Chan Patriarch, in an uninterrupted line starting with the Buddha, through direct and non-verbal transmission.

Legends

Bodhidharma inventing Chinese Martial Arts

Historically, it is unlikely that Bodhidharma invented kung fu. There are martial arts manuals that date back to at least the Han Dynasty (202 B.C.E.–220 C.E.), predating both Bodhidharma and the Shaolin Temple he stayed at. The codification of the martial arts by monks most likely began with military personnel who retired to monasteries or sought sanctuary there.

The Extensive Records of the Taiping Era record that, prior to Bodhidharma's arrival in China, monks practiced wrestling for recreation. Shaolin monastery records state that two of its very first monks, Hui Guang and Seng Chou, were experts in the martial arts, years before the arrival of Bodhidharma. The exercises attributed to Bodhidharma are consistent with Chinese qigong exercises and look little like Indian forms of bodywork like yoga. Scholarship by Chinese martial arts historians has demonstrated that the Yijin jing and Xisuijing are most likely Ming dynasty (1368-1644 C.E.) texts due to the presence of technical terminology from the Daoist "inner alchemy" (neidan) tradition which reached its maturity in the Song. This argument is summarized by modern historian Lin Boyuan in his Zhongguo wushu shi as follows:

As for the “Yi Jin Jing” (Muscle Change Classic), a spurious text attributed to Bodhidharma and included in the legend of his transmitting martial arts at the temple, it was writtin in the Ming dynasty, in 1624 C.E., by the Daoist priest Zining of Mt. Tiantai, and falsely attributed to Bodhidharma. Forged prefaces, attributed to the Tang general Li Jing and the Southern Song general Niu Hao were written. They say that, after Bodhidharma faced the wall for nine years at Shaolin temple, he left behind an iron chest; when the monks opened this chest they found the two books “Xi Sui Jing” (Marrow Washing Classic) and “Yi Jin Jing” within. The first book was taken by his disciple Huike, and disappeared; as for the second, “the monks selfishly coveted it, practicing the skills therein, falling into heterodox ways, and losing the correct purpose of cultivating the Real. The Shaolin monks have made some fame for themselves through their fighting skill; this is all due to having obtained this manuscript.” Based on this, Bodhidharma was claimed to be the ancestor of Shaolin martial arts. This manuscript is full of errors, absurdities and fantastic claims; it cannot be taken as a legitimate source. (Lin Boyuan, Zhongguo wushu shi, Wuzhou chubanshe, p. 183)

Bringing tea to China

Japanese legends hold that Bodhidharma “brought” tea to China when, frustrated with falling asleep during meditation, he cut off his eyelids and threw them behind him. When they hit the ground, tea bushes sprouted from them.

Even if tea plants did sprout from Bodhidharma’s eyelids, they would not have been the first tea plants in China as tea use there predates the arrival of Chan Buddhism. There is an early mention of tea being prepared by servants in a Chinese text of 50 b.c.e.. The first detailed description of tea-drinking is found in an ancient Chinese dictionary, noted by Kuo P'o in 350 C.E., almost two centuries before Bodhidharma came to China.

Daruma dolls

It is also reported that after years of meditation, Bodhidharma lost the usage of his legs. This legend is still alive in Japan, where legless Daruma dolls represent Bodhidharma, and are used to make wishes.

The lineage of Bodhidharma and his disciples

Although Bodhidharma is commonly said to have had two primary disciples (the monks Daoyu and Huike), a common voice in the "Records" of the Long Scroll is that of a Yuan, possibly identified with the nun Dharani who was said to have received Bodhidharma's flesh — his bones having been received by Daoyu, and his marrow received by Huike (see Zen for a detailed lineage of Chinese and Japanese Zen).

Works attributed to Bodhidharma

- The Bloodstream Sermon

- The Breakthrough Sermon

- The Outline of Practice

- Two Entrances

- The Wake-Up Sermon

See also

- Zen Buddhism

- Buddhism in China

- Culture hero

- List of Buddhist topics

External links

- Learn everything about Bodhidharma in the Official English Songshan Shaolinsi Temple Portal

- Zen and the Martial Arts by Ming Zheng Shakya (PDF)

- Bodhidharma

- Bodhidharma Museum Japan Gabi Greve

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Broughton, Jeffrey L. (1999). The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520219724.

- Tom Lowenstein, The Vision of the Buddha. Duncan Baird Publishers, London. ISBN 1903296919

- Red Pine, translator; The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma. North Point Press, New York. (1987)

- Alan Watts, The Way of Zen. ISBN 0375705104

- Paul Williams, Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. ISBN 0415025370

- Andy Ferguson, Zen's Chinese Heritage. ISBN 0861711637 contains a translation of The Outline of Practice

- Donald W. Mitchell, Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist Experience. New York: Oxford Universit Press, 2002. ISBN 0195139518

- Thomas Cleary and J.C. Cleary, The Blue Cliff Record. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1992. ISBN 0877736227

| Preceded by: Prajnatara |

Buddhist Patriach |

Succeeded by: Title Extinct |

| Preceded by: New Creation |

Chinese Ch'an Patriarch |

Succeeded by: Hui Ke |

Template:Buddhism2

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.