Difference between revisions of "Baryon" - New World Encyclopedia

| (27 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{copyedited}} | ||

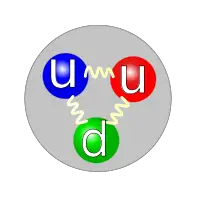

[[Image:Quark structure proton.svg|thumb|200px|A [[proton]] is an example of a baryon. It is composed of 2 up quarks (u) and 1 down quark (d).]] | [[Image:Quark structure proton.svg|thumb|200px|A [[proton]] is an example of a baryon. It is composed of 2 up quarks (u) and 1 down quark (d).]] | ||

| − | The term '''baryon''' usually refers to a [[subatomic particle]] composed of three [[quark]]s.<ref>[http://www.particleadventure.org/frameless/hadrons.html Hadrons: Baryons and Mesons] | + | The term '''baryon''' usually refers to a [[subatomic particle]] composed of three [[quark]]s.<ref>The Particle Adventure, [http://www.particleadventure.org/frameless/hadrons.html Hadrons: Baryons and Mesons.] Retrieved September 10, 2008.</ref> A more technical (and broader) definition is that it is a subatomic particle with a [[baryon number]] of 1. Baryons are a subset of [[hadron]]s, (which are particles made of quarks), and they participate in the [[strong interaction]]. They are also a subset of [[fermion]]s. Well-known examples of baryons are [[proton]]s and [[neutron]]s, which make up [[atomic nucleus|atomic nuclei]], but many unstable baryons have been found as well. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | Some "exotic" baryons, known as [[pentaquark]]s, are thought to be composed of four quarks and one antiquark, but their existence is not generally accepted. Each baryon has a corresponding antiparticle, called an '''anti-baryon''' | + | Some "exotic" baryons, known as [[pentaquark]]s, are thought to be composed of four quarks and one antiquark, but their existence is not generally accepted. Each baryon has a corresponding antiparticle, called an '''anti-baryon,''' in which quarks are replaced by their corresponding antiquarks. |

== Etymology == | == Etymology == | ||

| − | + | The term ''baryon'' is derived from the [[Greek language|Greek]] word ''{{polytonic|βαρύς}}'' ''(barys)'', meaning "heavy," because at the time of their naming it was believed that baryons were characterized by having greater mass than other particles. | |

| − | The term ''baryon'' is derived from the [[Greek language|Greek]] word ''{{polytonic|βαρύς}}'' | ||

==Basic properties== | ==Basic properties== | ||

| − | |||

Each baryon has an odd half-integer spin (such as {{frac|1|2}} or {{frac|3|2}}), where "spin" refers to the angular momentum quantum number. Baryons are therefore classified as ''[[fermion]]s''. They experience the [[strong nuclear force]] and are described by [[Fermi-Dirac statistics]], which apply to all particles obeying the [[Pauli exclusion principle]]. This stands in contrast to [[boson]]s, which do not obey the exclusion principle. | Each baryon has an odd half-integer spin (such as {{frac|1|2}} or {{frac|3|2}}), where "spin" refers to the angular momentum quantum number. Baryons are therefore classified as ''[[fermion]]s''. They experience the [[strong nuclear force]] and are described by [[Fermi-Dirac statistics]], which apply to all particles obeying the [[Pauli exclusion principle]]. This stands in contrast to [[boson]]s, which do not obey the exclusion principle. | ||

| − | Baryons, along with [[meson]]s, are [[hadron]]s, meaning they are particles composed of [[quark]]s. | + | Baryons, along with [[meson]]s, are [[hadron]]s, meaning they are particles composed of [[quark]]s. Each quark has a [[baryon number]] of B = {{frac|1|3}}, and each antiquark has a baryon number of B = −{{frac|1|3|}}. |

The term ''baryon number'' is defined as: | The term ''baryon number'' is defined as: | ||

| Line 21: | Line 20: | ||

: <math>N_{\overline{q}}</math> is the number of antiquarks. | : <math>N_{\overline{q}}</math> is the number of antiquarks. | ||

| − | The term "baryon" is usually used for ''triquarks'' | + | The term "baryon" is usually used for ''triquarks,'' that is, baryons made of three quarks. Thus, each baryon has a baryon number of 1 (B = {{frac|1|3}} + {{frac|1|3}} + {{frac|1|3}} = 1). |

| + | |||

| + | Some have suggested the existence of other, "exotic" baryons, such as pentaquarks—baryons made of four quarks and one antiquark (B = {{frac|1|3}} + {{frac|1|3}} + {{frac|1|3}} + {{frac|1|3}} − {{frac|1|3}} = 1)—but their existence is not generally accepted. Theoretically, heptaquarks (5 quarks, 2 antiquarks), nonaquarks (6 quarks, 3 antiquarks), and so forth could also exist. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Besides being associated with a spin number and a baryon number, each baryon has a quantum number known as ''strangeness''. This quantity is equal to -1 times the number of strange quarks present in the baryon.<ref>Hyper Physics, [http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/Hbase/particles/hadron.html Baryons.] Retrieved September 10, 2008.</ref> | ||

==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

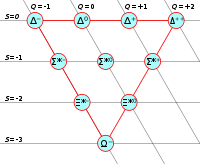

| − | [[Image:Baryon decuplet.svg|thumb|Combinations of three u, d or s-quarks with a total spin of 3/2 form the so-called '''baryon decuplet''' | + | [[Image:Baryon decuplet.svg|thumb|200px|Combinations of three u, d or s-quarks with a total spin of 3/2 form the so-called '''baryon decuplet.''']] |

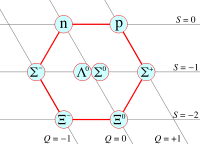

| − | [[Image:Baryon octet.svg|thumb|right|The '''octet''' of light spin-1/2 baryons.]] | + | [[Image:Baryon octet.svg|thumb|right|200px|The '''octet''' of light spin-1/2 baryons.]] |

Baryons are classified into groups according to their [[isospin]] values and [[quark]] content. There are six groups of triquarks: | Baryons are classified into groups according to their [[isospin]] values and [[quark]] content. There are six groups of triquarks: | ||

| Line 35: | Line 38: | ||

* [[Omega baryon|Omega]] ({{SubatomicParticle|Omega}}) | * [[Omega baryon|Omega]] ({{SubatomicParticle|Omega}}) | ||

| − | The rules for classification are defined by the [[Particle Data Group]]. The rules cover all the particles that can be made from three of each of the six quarks ([[up quark|up]], [[down quark|down]], [[strange quark|strange]], [[charm quark|charm]], [[bottom quark|bottom]], [[top quark|top]]), although baryons made of top quarks are not expected to exist because of the top quark's short lifetime. (The rules do not cover pentaquarks.)<ref name=PDGBaryonsymbols>M. Roos and C.G. Wohl | + | The rules for classification are defined by the [[Particle Data Group]]. The rules cover all the particles that can be made from three of each of the six quarks ([[up quark|up]], [[down quark|down]], [[strange quark|strange]], [[charm quark|charm]], [[bottom quark|bottom]], [[top quark|top]]), although baryons made of top quarks are not expected to exist because of the top quark's short lifetime. (The rules do not cover pentaquarks.)<ref name=PDGBaryonsymbols>M. Roos and C.G. Wohl, [http://pdg.lbl.gov/2007/reviews/namingrpp.pdf Naming Scheme for Hadrons,] ''J. Phys'' G 33:1. Retrieved September 10, 2008.</ref> According to these rules, the {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Up quark}}, {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Down quark}}, and {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Strange quark}} quarks are considered ''light,'' and the {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Charm quark}}, {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Bottom quark}}, and {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Top quark}} quarks are considered ''heavy''. |

Based on the rules, the following classification system has been set up: | Based on the rules, the following classification system has been set up: | ||

| − | * Baryons with three {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Up quark}} and/or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Down quark}} quarks are {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Nucleon}} | + | * Baryons with three {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Up quark}} and/or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Down quark}} quarks are grouped as {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Nucleon}} ([[isospin]] {{frac|1|2}}) or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Delta}} (isospin {{frac|3|2}}). |

| − | * Baryons with two {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Up quark}} and/or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Down quark}} quarks are {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Lambda}} | + | * Baryons with two {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Up quark}} and/or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Down quark}} quarks are grouped as {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Lambda}} (isospin 0) or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Sigma}} (isospin 1). If the third quark is heavy, its identity is given by a subscript. |

| − | * Baryons with one {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Up quark}} or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Down quark}} quark are {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Xi}} | + | * Baryons with one {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Up quark}} or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Down quark}} quark are placed in the group {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Xi}} (isospin {{frac|1|2}}). One or two subscripts are used if one or both of the remaining quarks are heavy. |

| − | * Baryons with no {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Up quark}} or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Down quark}} quarks are {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Omega}} | + | * Baryons with no {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Up quark}} or {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Down quark}} quarks are placed in the group {{SubatomicParticle|link=yes|Omega}} (isospin 0), and subscripts indicate any heavy quark content. |

| − | * | + | * Some baryons decay strongly, in which case their masses are shown as part of their names. For example, Sigmas ({{SubatomicParticle|Sigma}}) and Omegas ({{SubatomicParticle|Omega}}) do not decay strongly, but Deltas ({{nowrap|{{SubatomicParticle|Delta}}(1232)}}), and charmed Xis ({{nowrap|{{SubatomicParticle|Charmed Xi+}}(2645)}}) do. |

| + | |||

| + | Given that quarks carry charge, knowledge of the charge of a particle indirectly gives the quark content. For example, the rules say that the {{SubatomicParticle|Bottom sigma}} contains a bottom and some combination of two up and/or down quarks. A {{SubatomicParticle|Bottom sigma0}} must be one up quark (Q={{frac|2|3}}), one down quark (Q=−{{frac|1|3}}), and one bottom quark (Q=−{{frac|1|3}}) to have the correct charge (Q=0). | ||

| − | + | The number of baryons within one group (excluding resonances) is given by the number of isospin projections possible (2 × isospin + 1). For example, there are four {{SubatomicParticle|Delta}}'s, corresponding to the four isospin projections of the isospin value I = {{frac|3|2}}: {{SubatomicParticle|Delta++}} (I<sub>z</sub> = {{frac|3|2}}), {{SubatomicParticle|Delta+}}(I<sub>z</sub> = {{frac|1|2}}), {{SubatomicParticle|Delta0}}(I<sub>z</sub> = −{{frac|1|2}}), and {{SubatomicParticle|Delta-}}(I<sub>z</sub> = −{{frac|3|2}}). Another example would be the three {{SubatomicParticle|Bottom sigma}}'s, corresponding to the three isospin projections of the isospin value I = 1: {{SubatomicParticle|Bottom sigma+}} (I<sub>z</sub> = 1), {{SubatomicParticle|Bottom sigma0}}(I<sub>z</sub> = 0), and {{SubatomicParticle|Bottom sigma-}}(I<sub>z</sub> = −1). | |

| − | + | === Charmed baryons === | |

| + | Baryons that are composed of at least one charm quark are known as ''charmed baryons''. | ||

==Baryonic matter== | ==Baryonic matter== | ||

| − | '''Baryonic [[matter]]''' is matter composed mostly of baryons (by mass) | + | '''Baryonic [[matter]]''' is matter composed mostly of baryons (by mass). It includes [[atom]]s of all types, and thus includes nearly all types of matter that we may encounter or [[experience]] in everyday life, including the matter that constitutes human bodies. '''Non-baryonic matter,''' as implied by the name, is any sort of matter that is not primarily composed of baryons. It may include such ordinary matter as [[neutrino]]s or free [[electron]]s, but it may also include exotic species of non-baryonic [[dark matter]], such as [[supersymmetry|supersymmetric particles]], [[axion]]s, or [[black hole]]s. |

| + | |||

| + | The distinction between baryonic and non-baryonic matter is important in [[physical cosmology|cosmology]], because [[Big Bang nucleosynthesis]] models set tight constraints on the amount of baryonic matter present in the early [[universe]]. | ||

The very existence of baryons is also a significant issue in cosmology because current theory assumes that the Big Bang produced a state with equal amounts of baryons and anti-baryons. The process by which baryons came to outnumber their antiparticles is called ''[[baryogenesis]]''. (This is distinct from a process by which [[lepton]]s account for the predominance of matter over antimatter, known as ''[[leptogenesis (physics)|leptogenesis]]''.) | The very existence of baryons is also a significant issue in cosmology because current theory assumes that the Big Bang produced a state with equal amounts of baryons and anti-baryons. The process by which baryons came to outnumber their antiparticles is called ''[[baryogenesis]]''. (This is distinct from a process by which [[lepton]]s account for the predominance of matter over antimatter, known as ''[[leptogenesis (physics)|leptogenesis]]''.) | ||

==Baryogenesis== | ==Baryogenesis== | ||

| − | Experiments are consistent with the number of quarks in the universe being a constant and, more specifically, | + | Experiments are consistent with the number of quarks in the universe being a constant and, more specifically, the number of [[baryon]]s being a constant; in technical language, the total [[baryon number]] appears to be ''[[conservation law|conserved]].'' Within the prevailing [[Standard Model]] of particle physics, the number of baryons may change in multiples of three due to the action of [[sphaleron]]s, although this is rare and has not been observed experimentally. Some [[grand unified theory|grand unified theories]] of particle physics also predict that a single [[proton]] can decay, changing the baryon number by one; however, this has not yet been observed experimentally. The [[baryogenesis|excess of baryons over antibaryons]] in the present universe is thought to be due to non-conservation of baryon number in the very early universe, though this is not well understood. |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | |||

* [[Antimatter]] | * [[Antimatter]] | ||

* [[Atom]] | * [[Atom]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [[Dark matter]] | * [[Dark matter]] | ||

* [[Fermion]] | * [[Fermion]] | ||

| Line 69: | Line 73: | ||

* [[Lepton]] | * [[Lepton]] | ||

* [[Matter]] | * [[Matter]] | ||

| + | * [[Meson]] | ||

* [[Neutron]] | * [[Neutron]] | ||

* [[Particle physics]] | * [[Particle physics]] | ||

* [[Proton]] | * [[Proton]] | ||

* [[Quark]] | * [[Quark]] | ||

| + | * [[Standard Model]] | ||

* [[Subatomic particle]] | * [[Subatomic particle]] | ||

| Line 79: | Line 85: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Cottingham, W.N., and D.A. Greenwood. ''An Introduction to the Standard Model of Particle Physics,'' 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0521852494 | |

| − | * Griffiths, David J | + | * Griffiths, David J. ''Introduction to Elementary Particles''. New York: Wiley, 1987. ISBN 0471603864 |

| − | * Halzen, Francis, and Alan D. Martin | + | * Halzen, Francis, and Alan D. Martin. ''Quarks and Leptons: An Introductory Course in Modern Particle Physics''. New York: Wiley, 1984. ISBN 0471887412 |

| − | * Povh, Bogdan | + | * Martin, B. R. ''Nuclear and Particle Physics: An Introduction''. Chichester: John Wiley, 2006. ISBN 978-0470025321 |

| − | * Veltman, Martinus | + | * Povh, Bogdan. ''Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts''. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1995. ISBN 0387594396 |

| + | * Veltman, Martinus. ''Facts and Mysteries in Elementary Particle Physics.'' River Edge, NJ: World Scientific, 2003. ISBN 981238149X | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| + | All links retrieved September 20, 2023. | ||

| − | * [http:// | + | * [http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/Hbase/particles/hadron.html Baryons]. |

| + | * [http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/particles/baryon.html#c1 Table of Baryons]. | ||

| + | * [http://pdg.lbl.gov/ The Review of Particle Physics]. Particle Data Group. | ||

| − | + | ---- | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{particles}} | {{particles}} | ||

[[Category:Physical sciences]] | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Physics]] | [[Category:Physics]] | ||

| − | |||

[[Category:Particle physics]] | [[Category:Particle physics]] | ||

| − | {{credit|236246949}} | + | {{credit|Baryon|236246949|Baryon_number|230664144|Charmed_baryon|228720132}} |

Latest revision as of 11:02, 20 September 2023

The term baryon usually refers to a subatomic particle composed of three quarks.[1] A more technical (and broader) definition is that it is a subatomic particle with a baryon number of 1. Baryons are a subset of hadrons, (which are particles made of quarks), and they participate in the strong interaction. They are also a subset of fermions. Well-known examples of baryons are protons and neutrons, which make up atomic nuclei, but many unstable baryons have been found as well.

Some "exotic" baryons, known as pentaquarks, are thought to be composed of four quarks and one antiquark, but their existence is not generally accepted. Each baryon has a corresponding antiparticle, called an anti-baryon, in which quarks are replaced by their corresponding antiquarks.

Etymology

The term baryon is derived from the Greek word βαρύς (barys), meaning "heavy," because at the time of their naming it was believed that baryons were characterized by having greater mass than other particles.

Basic properties

Each baryon has an odd half-integer spin (such as 1⁄2 or 3⁄2), where "spin" refers to the angular momentum quantum number. Baryons are therefore classified as fermions. They experience the strong nuclear force and are described by Fermi-Dirac statistics, which apply to all particles obeying the Pauli exclusion principle. This stands in contrast to bosons, which do not obey the exclusion principle.

Baryons, along with mesons, are hadrons, meaning they are particles composed of quarks. Each quark has a baryon number of B = 1⁄3, and each antiquark has a baryon number of B = −1⁄3.

The term baryon number is defined as:

where

- is the number of quarks, and

- is the number of antiquarks.

The term "baryon" is usually used for triquarks, that is, baryons made of three quarks. Thus, each baryon has a baryon number of 1 (B = 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 = 1).

Some have suggested the existence of other, "exotic" baryons, such as pentaquarks—baryons made of four quarks and one antiquark (B = 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 + 1⁄3 − 1⁄3 = 1)—but their existence is not generally accepted. Theoretically, heptaquarks (5 quarks, 2 antiquarks), nonaquarks (6 quarks, 3 antiquarks), and so forth could also exist.

Besides being associated with a spin number and a baryon number, each baryon has a quantum number known as strangeness. This quantity is equal to -1 times the number of strange quarks present in the baryon.[2]

Classification

Baryons are classified into groups according to their isospin values and quark content. There are six groups of triquarks:

- Nucleon (N)

- Delta (Δ)

- Lambda (Λ)

- Sigma (Σ)

- Xi (Ξ)

- Omega (Ω)

The rules for classification are defined by the Particle Data Group. The rules cover all the particles that can be made from three of each of the six quarks (up, down, strange, charm, bottom, top), although baryons made of top quarks are not expected to exist because of the top quark's short lifetime. (The rules do not cover pentaquarks.)[3] According to these rules, the u, d, and s quarks are considered light, and the c, b, and t quarks are considered heavy.

Based on the rules, the following classification system has been set up:

- Baryons with three u and/or d quarks are grouped as N (isospin 1⁄2) or Δ (isospin 3⁄2).

- Baryons with two u and/or d quarks are grouped as Λ (isospin 0) or Σ (isospin 1). If the third quark is heavy, its identity is given by a subscript.

- Baryons with one u or d quark are placed in the group Ξ (isospin 1⁄2). One or two subscripts are used if one or both of the remaining quarks are heavy.

- Baryons with no u or d quarks are placed in the group Ω (isospin 0), and subscripts indicate any heavy quark content.

- Some baryons decay strongly, in which case their masses are shown as part of their names. For example, Sigmas (Σ) and Omegas (Ω) do not decay strongly, but Deltas (Δ(1232)), and charmed Xis (Ξ+c(2645)) do.

Given that quarks carry charge, knowledge of the charge of a particle indirectly gives the quark content. For example, the rules say that the Σb contains a bottom and some combination of two up and/or down quarks. A Σ0b must be one up quark (Q=2⁄3), one down quark (Q=−1⁄3), and one bottom quark (Q=−1⁄3) to have the correct charge (Q=0).

The number of baryons within one group (excluding resonances) is given by the number of isospin projections possible (2 × isospin + 1). For example, there are four Δ's, corresponding to the four isospin projections of the isospin value I = 3⁄2: Δ++ (Iz = 3⁄2), Δ+(Iz = 1⁄2), Δ0(Iz = −1⁄2), and Δ−(Iz = −3⁄2). Another example would be the three Σb's, corresponding to the three isospin projections of the isospin value I = 1: Σ+b (Iz = 1), Σ0b(Iz = 0), and Σ−b(Iz = −1).

Charmed baryons

Baryons that are composed of at least one charm quark are known as charmed baryons.

Baryonic matter

Baryonic matter is matter composed mostly of baryons (by mass). It includes atoms of all types, and thus includes nearly all types of matter that we may encounter or experience in everyday life, including the matter that constitutes human bodies. Non-baryonic matter, as implied by the name, is any sort of matter that is not primarily composed of baryons. It may include such ordinary matter as neutrinos or free electrons, but it may also include exotic species of non-baryonic dark matter, such as supersymmetric particles, axions, or black holes.

The distinction between baryonic and non-baryonic matter is important in cosmology, because Big Bang nucleosynthesis models set tight constraints on the amount of baryonic matter present in the early universe.

The very existence of baryons is also a significant issue in cosmology because current theory assumes that the Big Bang produced a state with equal amounts of baryons and anti-baryons. The process by which baryons came to outnumber their antiparticles is called baryogenesis. (This is distinct from a process by which leptons account for the predominance of matter over antimatter, known as leptogenesis.)

Baryogenesis

Experiments are consistent with the number of quarks in the universe being a constant and, more specifically, the number of baryons being a constant; in technical language, the total baryon number appears to be conserved. Within the prevailing Standard Model of particle physics, the number of baryons may change in multiples of three due to the action of sphalerons, although this is rare and has not been observed experimentally. Some grand unified theories of particle physics also predict that a single proton can decay, changing the baryon number by one; however, this has not yet been observed experimentally. The excess of baryons over antibaryons in the present universe is thought to be due to non-conservation of baryon number in the very early universe, though this is not well understood.

See also

- Antimatter

- Atom

- Dark matter

- Fermion

- Hadron

- Lepton

- Matter

- Meson

- Neutron

- Particle physics

- Proton

- Quark

- Standard Model

- Subatomic particle

Notes

- ↑ The Particle Adventure, Hadrons: Baryons and Mesons. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ↑ Hyper Physics, Baryons. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ↑ M. Roos and C.G. Wohl, Naming Scheme for Hadrons, J. Phys G 33:1. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cottingham, W.N., and D.A. Greenwood. An Introduction to the Standard Model of Particle Physics, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0521852494

- Griffiths, David J. Introduction to Elementary Particles. New York: Wiley, 1987. ISBN 0471603864

- Halzen, Francis, and Alan D. Martin. Quarks and Leptons: An Introductory Course in Modern Particle Physics. New York: Wiley, 1984. ISBN 0471887412

- Martin, B. R. Nuclear and Particle Physics: An Introduction. Chichester: John Wiley, 2006. ISBN 978-0470025321

- Povh, Bogdan. Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1995. ISBN 0387594396

- Veltman, Martinus. Facts and Mysteries in Elementary Particle Physics. River Edge, NJ: World Scientific, 2003. ISBN 981238149X

External links

All links retrieved September 20, 2023.

- Baryons.

- Table of Baryons.

- The Review of Particle Physics. Particle Data Group.

| Particles in physics | |

|---|---|

| elementary particles | Elementary fermions: Quarks: u · d · s · c · b · t • Leptons: e · μ · τ · νe · νμ · ντ Elementary bosons: Gauge bosons: γ · g · W± · Z0 • Ghosts |

| Composite particles | Hadrons: Baryons(list)/Hyperons/Nucleons: p · n · Δ · Λ · Σ · Ξ · Ω · Ξb • Mesons(list)/Quarkonia: π · K · ρ · J/ψ · Υ Other: Atomic nucleus • Atoms • Molecules • Positronium |

| Hypothetical elementary particles | Superpartners: Axino · Dilatino · Chargino · Gluino · Gravitino · Higgsino · Neutralino · Sfermion · Slepton · Squark Other: Axion · Dilaton · Goldstone boson · Graviton · Higgs boson · Tachyon · X · Y · W' · Z' |

| Hypothetical composite particles | Exotic hadrons: Exotic baryons: Pentaquark • Exotic mesons: Glueball · Tetraquark Other: Mesonic molecule |

| Quasiparticles | Davydov soliton · Exciton · Magnon · Phonon · Plasmon · Polariton · Polaron |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.