Difference between revisions of "Baltasar Gracian y Morales" - New World Encyclopedia

MaedaMartha (talk | contribs) |

MaedaMartha (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:Baltasar-gracian.gif|right]] | [[Image:Baltasar-gracian.gif|right]] | ||

<!-- Image with questionable fair-use claim removed: [[Image:Gracian.jpg|right|300px]] —> | <!-- Image with questionable fair-use claim removed: [[Image:Gracian.jpg|right|300px]] —> | ||

| − | |||

| − | Gracian wrote a number of literary works, including political commentary, guidance and practical advice for life, and ''Criticón'', an allegorical and pessimistic novel with philosophical overtones, published in three parts in 1651, 1653, and 1657, which contrasted an idyllic primitive life with the evils of civilization. His literary efforts were not consistent with the anonymity of Jesuit life; though he used several pen names, he was chastised and exiled for publishing ''Criticón'' without the permission of his superiors. | + | '''Baltasar Gracián y Morales''' (January 8, 1601 - December 6, 1658) was a [[Spain|Spanish]] [[Jesuit order|Jesuit]] philosopher, prose writer and [[baroque]] moralist. After receiving a Jesuit education which included humanities and [[literature]] as well as [[philosophy]] and [[theology]], he entered the Jesuit order in 1633 and became a teacher and eventually of the Jesuit college of Tarragona. Gracián is the most representative writer of the Spanish baroque literary style known as ''Conceptismo'' (Conceptism), which is characterized by the use of terse and subtle displays of exaggerated wit to illustrate ideas. |

| + | |||

| + | Gracian wrote a number of literary works, including political commentary, guidance and practical advice for life, and ''Criticón'', an allegorical and pessimistic novel with philosophical overtones, published in three parts in 1651, 1653, and 1657, which contrasted an idyllic primitive life with the evils of civilization. His literary efforts were not consistent with the anonymity of Jesuit life; though he used several pen names, he was chastised and exiled for publishing ''Criticón'' without the permission of his superiors. His most famous book outside of Spain is ''Oráculo manual y arte de prudentia'' (1647), a collection of three hundred maxims, translated into German by [[Schopenhauer]], and into English by [[Joseph Jacobs]] in 1892 as ''The Art of Wordly Wisdom. '' | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Life== | ||

| + | '''Baltasar Gracián y Morales''' was born January 8, 1601, at Belmonte, a suburb of Calatayud, in the kingdom of Aragon, [[Spain]], the son of a doctor from a noble family. Baltasar recounts that he was raised in the house of his uncle, the priest Antonio Gracian, at Toledo, indicating that his parents died when he was very young. All three of Gracian’s brothers took religious orders: Felipe, the eldest, joined the order of St. Francis; the next brother, Pedro, became a Trinitarian; and the third, Raymundo, a Carmelite. | ||

| + | Gracian was among the first to be educated according to the new Jesuit ''Ratio Studiorum'' (published 1599), a curriculum which incorporated [[literature]], [[drama]] and the humanities along with [[theology]], [[philosophy]] and the sciences. After studying at a Jesuit school in Zaragoza from 1616 to 1619, Baltasar became a novice in the Company of Jesus. He studied philosophy at the College of Calatayud in 1621 and 1623 and theology in Zaragoza. He was ordained in 1627, assumed the vows of the [[Jesuit Order|Jesuits]] in 1633 or 1635, and dedicated himself to teaching in various Jesuit schools. | ||

| + | His became a close friend of a local scholar, Don Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa, a dilettante who lived at Huesca and collected coins, medals, and other artifacts. Gracian appears to have shared his interests, for Lastanosa mentions him in a description of his own collection cabinet. A correspondence between de Lastanosa and Gracian, which was commented on by Latassa, indicates that Gracian moved frequently, going from [[Madrid]] to Zarogoza, and thence to Tarragona. Lastanoza assisted Gracian in the publication of most of his works. | ||

| − | + | Another source relates that Gracian was often invited to dinner by Philip III. He acquired fame as a preacher, although some of his oratorical displays, such as reading a letter sent from Hell from the pulpit, were frowned upon by his superiors. Eventually he was named Rector of the Jesuit college of Tarragona. He wrote several works proposing models for courtly conduct such as ''El héroe'' (''The Hero'') (1637), ''El político'' (''The Politician''), and ''El discreto'' (''The One''or “The Compleat Gentleman”) (1646). During the Spanish war with Catalonia and [[France]], he was chaplain of the army that liberated Lleida in 1646. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | He acquired fame as a preacher, although some of his oratorical displays, such as reading a letter sent from Hell from the pulpit, were frowned upon by his superiors. Eventually he was named Rector of the Jesuit college of Tarragona. He wrote several works proposing models for courtly conduct such as ''El héroe'' (''The Hero'') (1637), ''El político'' (''The Politician''), and ''El discreto'' (''The One''or “The Compleat Gentleman”) (1646). During the Spanish war with Catalonia and [[France]], he was chaplain of the army that liberated Lleida in 1646. | ||

| − | In 1651, Gracian published the first part of the ''Criticón'' (''Faultfinder'') without the permission of his Jesuit superiors, whom he repeatedly disobeyed. This | + | In 1651, Gracian published the first part of the ''Criticón'' (''Faultfinder'') without the permission of his Jesuit superiors, whom he repeatedly disobeyed. This provoked the displeasure of he Order's authorities. Ignoring their reprimands, he published the third part of ''Criticón'' in 1657, and was sanctioned and exiled to Graus, where he tried unsuccessfully to leave the order. He died in 1658 and is buried in Tarazona near Zaragoza in the province of Aragon. |

==Thought and Works== | ==Thought and Works== | ||

| − | Gracián wrote in a concentrated, terse style and is the most representative writer of the Spanish [[ | + | Gracián wrote in a concentrated, terse style and is the most representative writer of the Spanish [[baroque]] literary style known as ''Conceptismo'' (Conceptism), of which he was the most important theoretician. ''Conceptismo'' is characterized by the use of terse and subtle displays of exaggerated wit to illustrate ideas. Gracian’s ''Agudeza y arte de ingenio'' (''Wit and the Art of Inventiveness'') (1643) was at once a poetic, a rhetoric and an [[anthology]] of the conceptist style. |

| − | Gracian’s earliest works, El héroe (1637) and El político (1640) were treatises on the ideal qualities for political leaders. His most famous book outside of Spain is Oráculo manual y arte de prudentia (1647), a collection of three hundred maxims, translated by Joseph Jacobs in 1892 as The Art of Wordly Wisdom. In contrast to Ignatius Loyola's Exercitia, which was a manual of prayer and devotion, Oráculo offered practical advice for social life. | + | Gracian’s earliest works, ''El héroe'' (1637) and ''El político'' (1640) were treatises on the ideal qualities for political leaders. His most famous book outside of [[Spain]] is ''Oráculo manual y arte de prudentia'' (1647), a collection of three hundred maxims, translated by [[Joseph Jacobs]] in 1892 as ''The Art of Wordly Wisdom''. In contrast to Ignatius Loyola's Exercitia, which was a manual of prayer and devotion, ''Oráculo'' offered practical advice for social life. |

| − | The only one of his works which bears Gracián's name is ''El Comulgatorio'' (1655); his more important books were issued under the pseudonym of Lorenzo Gracián (a brother of the writer) or under the anagram of Gracía de Marlones. In 1657 Gracián was punished by the Jesuit authorities for publishing ''El Criticón'' without his superior's permission, but they did not make any objection to the substance of the book. | + | The only one of his works which bears Gracián's name is ''El Comulgatorio'' (1655), a devotional work; his more important books were issued under the pseudonym of Lorenzo Gracián (a fictional brother of the writer) or under the anagram of Gracía de Marlones. In 1657 Gracián was punished by the Jesuit authorities for publishing ''El Criticón'' without his superior's permission, but they did not make any objection to the substance of the book. |

| + | |||

| + | Gracian influenced [[La Rochefoucauld]], and later [[Voltaire]], [[Nietzsche]], and [[Schopenhauer]], who considered Gracián's ''El criticón'' (3 parts, 1651–57) one of the best books ever written, and translated ''Oráculo manual y arte de prudential'' into German. | ||

| − | |||

==The ''Criticón''== | ==The ''Criticón''== | ||

| − | ''Criticón'', an allegorical and pessimistic novel with philosophical overtones, was published in three parts in 1651, 1653, and 1657. It achieved fame in Europe, especially in the German-speaking countries, and was, without a doubt, the author's masterpiece and one of the great works of the Siglo de Oro. ''Criticón'' contrasted an idyllic primitive life with the evils of civilization. Its many vicissitudes, and the numerous adventures to which the characters are subjected, recalled the Byzantine style of novel; its satirical portrayal of society recalls the [[picaresque novel]]. A long pilgrimage is undertaken by the main characters, Critilo, the "critical man" who personifies disillusionment, and Andrenio, the "natural man" who represents innocence and primitive impulses. The author constantly uses a perspectivist technique to unfold the story according to the criteria or points of view of both characters, but in an antithetical rather than a plural way. | + | ''Criticón'', an allegorical and pessimistic novel with philosophical overtones, was published in three parts in 1651, 1653, and 1657. It achieved fame in Europe, especially in the German-speaking countries, and was, without a doubt, the author's masterpiece and one of the great works of the Siglo de Oro. ''Criticón'' contrasted an idyllic primitive life with the evils of civilization. Its many vicissitudes, and the numerous adventures to which the characters are subjected, recalled the [[Byzantine]] style of novel; its satirical portrayal of society recalls the [[picaresque novel]]. A long pilgrimage is undertaken by the main characters, Critilo, the "critical man" who personifies disillusionment, and Andrenio, the "natural man" who represents innocence and primitive impulses. The author constantly uses a perspectivist technique to unfold the story according to the criteria or points of view of both characters, but in an antithetical rather than a plural way. |

The following is a brief sketch of the Criticón, a complex work that demands detailed study: | The following is a brief sketch of the Criticón, a complex work that demands detailed study: | ||

| − | Critilo, man of the world, is shipwrecked on the coast of the island of Santa Elena, where he meets Andrenio, the natural man, who has grown up completely ignorant of civilization. Together they undertake a long voyage to the Isle of Immortality, travelling the long and prickly road of life. In the first part, "En la primavera de la niñez" ("In the Spring of Youth"), they join the royal court, where they suffer all manner of disappointments; in the second part, "En el otoño de la varonil edad" ("In the Autumn of the Age of Manliness"), they pass through Aragon, where they visit the house of Salastano (an [[anagram]] of the name of Gracián's friend Lastanosa), and travel to France, which the author calls the "wasteland of Hipocrinda," populated entirely by hypocrites and dunces, ending with a visit to a house of lunatics. In the third part, "En el invierno de la vejez" ("In the Winter of Old Age"), they arrive in [[Rome]], where they encounter an academy where they meet the most inventive of men, arriving finally at the Isle of Immortality. | + | Critilo, man of the world, is shipwrecked on the coast of the island of Santa Elena, where he meets Andrenio, the natural man, who has grown up completely ignorant of civilization. Together they undertake a long voyage to the Isle of Immortality, travelling the long and prickly road of life. In the first part, "''En la primavera de la niñez" ("In the Spring of Youth"''), they join the royal court, where they suffer all manner of disappointments; in the second part, ''"En el otoño de la varonil edad" ("In the Autumn of the Age of Manliness"''), they pass through Aragon, where they visit the house of Salastano (an [[anagram]] of the name of Gracián's friend Lastanosa), and travel to France, which the author calls the "wasteland of Hipocrinda," populated entirely by hypocrites and dunces, ending with a visit to a house of lunatics. In the third part, ''"En el invierno de la vejez" ("In the Winter of Old Age")'', they arrive in [[Rome]], where they encounter an academy where they meet the most inventive of men, arriving finally at the Isle of Immortality. |

| − | + | [[Daniel Defoe|Defoe]] is alleged to have found the germ of his story ''[[Robinson Crusoe]]'' in ''El criticón''. | |

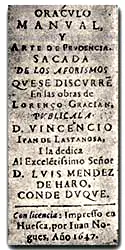

[[Image:Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia.png|left]] | [[Image:Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia.png|left]] | ||

| Line 38: | Line 42: | ||

==The Art of Worldly Wisdom== | ==The Art of Worldly Wisdom== | ||

| − | Gracián's style, generically called conceptism, is characterized by ellipsis (a rhetorical device in which the narrative skips over | + | Gracián's style, generically called "conceptism," is characterized by ellipsis (a rhetorical device in which the narrative skips over scenes) and the concentration of a maximum of meaning in a minimum of form, an approach referred to in Spanish as ''agudeza'' (wit). Gracian brought ''agudeza'' to its extreme in the ''Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia'' (literally ''The Oracle, a Manual of the Art of Discretion'', commonly translated as ''The Art of Worldly Wisdom'') (1637), which is almost entirely comprised of three hundred maxims with commentary. He constantly plays with words: each phrase becomes a puzzle, using the most diverse rhetorical devices. |

:i Everything is already at its highest point (Todo está ya en su punto) | :i Everything is already at its highest point (Todo está ya en su punto) | ||

:iii Keep Matters for a Time in Suspense (Llevar sus cosas con suspencion) | :iii Keep Matters for a Time in Suspense (Llevar sus cosas con suspencion) | ||

| Line 51: | Line 55: | ||

Baltasar Gracián, ''Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia'' | Baltasar Gracián, ''Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia'' | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Works== | ==Works== | ||

* ''El héroe'' (1637, ''The Hero''), a criticism of Niccolò Machiavelli|Machiavelli drawing a portrait of the ideal Christian leader. | * ''El héroe'' (1637, ''The Hero''), a criticism of Niccolò Machiavelli|Machiavelli drawing a portrait of the ideal Christian leader. | ||

| Line 67: | Line 68: | ||

| − | *Foster, Virginia Ramos. 1975. Baltasar Gracián. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN: 080572396X 9780805723960 9780805723960 080572396X | + | *Foster, Virginia Ramos. 1975. ''Baltasar Gracián''. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN: 080572396X 9780805723960 9780805723960 080572396X |

| − | *García Casanova, Juan Francisco, and José María Andreu Celma. 2003. El mundo de Baltasar Gracián: filosofía y literatura en el barroco. Granada [Spain]: Universidad de Granada. ISBN: 843382886X 9788433828866 9788433828866 843382886X | + | *García Casanova, Juan Francisco, and José María Andreu Celma. 2003. ''El mundo de Baltasar Gracián: filosofía y literatura en el barroco.'' Granada [Spain]: Universidad de Granada. ISBN: 843382886X 9788433828866 9788433828866 843382886X |

| − | *Gracian, Baltasar, and Martin Fischer. 1993. The art of worldly wisdom: a collection of aphorisms from the work of Baltasar Gracian. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN: 1566191335 9781566191333 9781566191333 1566191335 | + | *Gracian, Baltasar, and Martin Fischer. 1993. ''The art of worldly wisdom: a collection of aphorisms from the work of Baltasar Gracian''. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN: 1566191335 9781566191333 9781566191333 1566191335 |

| − | *Hafter, Monroe Z. 1966. Gracián and perfection; Spanish moralists of the seventeenth century. Harvard studies in Romance languages, v. 30. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC: 346894 | + | *Hafter, Monroe Z. 1966. ''Gracián and perfection; Spanish moralists of the seventeenth century.'' Harvard studies in Romance languages, v. 30. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC: 346894 |

| − | *Kassier, Theodore L. 1976. The truth disguised: allegorical structure and technique in Gracian's "Criticon". London: Tamesis. ISBN: 0729300064 : 9780729300063 9780729300063 0729300064 | + | *Kassier, Theodore L. 1976. ''The truth disguised: allegorical structure and technique in Gracian's "Criticon".'' London: Tamesis. ISBN: 0729300064 : 9780729300063 9780729300063 0729300064 |

| − | *Sánchez, Francisco J. 2003. An early bourgeois literature in golden age Spain: Lazarillo de Tormes, Guzmán de Alfarache and Baltasar Gracián. North Carolina studies in the Romance languages and literatures. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN: 0807892807 9780807892800 9780807892800 0807892807 | + | *Sánchez, Francisco J. 2003. ''An early bourgeois literature in golden age Spain: Lazarillo de Tormes, Guzmán de Alfarache and Baltasar Gracián.'' North Carolina studies in the Romance languages and literatures. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN: 0807892807 9780807892800 9780807892800 0807892807 |

| − | *Spadaccini, Nicholas, and Jenaro Taléns. 1997. Rhetoric and politics: Baltasar Gracián and the new world order. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN: 0816629102 9780816629107 9780816629107 0816629102 0816629110 9780816629114 9780816629114 0816629110 | + | *Spadaccini, Nicholas, and Jenaro Taléns. 1997. ''Rhetoric and politics: Baltasar Gracián and the new world order.'' Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN: 0816629102 9780816629107 9780816629107 0816629102 0816629110 9780816629114 9780816629114 0816629110 |

*{{1911}} | *{{1911}} | ||

** The 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' in turn gives the following references: See Karl Borinski, ''Baltasar Gracián und die Hoflitteratur in Deutschland'' (Halle, 1894); Benedetto Croce, ''I Trattatisti Italiani del Concettismo e Baltasar Gracián'' (Napoli, 1899); Narciso José Lin y Heredia, ''Baltasar Gracián'' (Madrid, 1902). Schopenhauer and Joseph Jacobs have respectively translated the ''Oráculo manual'' into German and English. | ** The 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' in turn gives the following references: See Karl Borinski, ''Baltasar Gracián und die Hoflitteratur in Deutschland'' (Halle, 1894); Benedetto Croce, ''I Trattatisti Italiani del Concettismo e Baltasar Gracián'' (Napoli, 1899); Narciso José Lin y Heredia, ''Baltasar Gracián'' (Madrid, 1902). Schopenhauer and Joseph Jacobs have respectively translated the ''Oráculo manual'' into German and English. | ||

| Line 96: | Line 97: | ||

{{Link FA|es}} | {{Link FA|es}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit|102611991}} | {{Credit|102611991}} | ||

Revision as of 03:46, 19 March 2007

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (January 8, 1601 - December 6, 1658) was a Spanish Jesuit philosopher, prose writer and baroque moralist. After receiving a Jesuit education which included humanities and literature as well as philosophy and theology, he entered the Jesuit order in 1633 and became a teacher and eventually of the Jesuit college of Tarragona. Gracián is the most representative writer of the Spanish baroque literary style known as Conceptismo (Conceptism), which is characterized by the use of terse and subtle displays of exaggerated wit to illustrate ideas.

Gracian wrote a number of literary works, including political commentary, guidance and practical advice for life, and Criticón, an allegorical and pessimistic novel with philosophical overtones, published in three parts in 1651, 1653, and 1657, which contrasted an idyllic primitive life with the evils of civilization. His literary efforts were not consistent with the anonymity of Jesuit life; though he used several pen names, he was chastised and exiled for publishing Criticón without the permission of his superiors. His most famous book outside of Spain is Oráculo manual y arte de prudentia (1647), a collection of three hundred maxims, translated into German by Schopenhauer, and into English by Joseph Jacobs in 1892 as The Art of Wordly Wisdom.

Life

Baltasar Gracián y Morales was born January 8, 1601, at Belmonte, a suburb of Calatayud, in the kingdom of Aragon, Spain, the son of a doctor from a noble family. Baltasar recounts that he was raised in the house of his uncle, the priest Antonio Gracian, at Toledo, indicating that his parents died when he was very young. All three of Gracian’s brothers took religious orders: Felipe, the eldest, joined the order of St. Francis; the next brother, Pedro, became a Trinitarian; and the third, Raymundo, a Carmelite.

Gracian was among the first to be educated according to the new Jesuit Ratio Studiorum (published 1599), a curriculum which incorporated literature, drama and the humanities along with theology, philosophy and the sciences. After studying at a Jesuit school in Zaragoza from 1616 to 1619, Baltasar became a novice in the Company of Jesus. He studied philosophy at the College of Calatayud in 1621 and 1623 and theology in Zaragoza. He was ordained in 1627, assumed the vows of the Jesuits in 1633 or 1635, and dedicated himself to teaching in various Jesuit schools.

His became a close friend of a local scholar, Don Vincencio Juan de Lastanosa, a dilettante who lived at Huesca and collected coins, medals, and other artifacts. Gracian appears to have shared his interests, for Lastanosa mentions him in a description of his own collection cabinet. A correspondence between de Lastanosa and Gracian, which was commented on by Latassa, indicates that Gracian moved frequently, going from Madrid to Zarogoza, and thence to Tarragona. Lastanoza assisted Gracian in the publication of most of his works.

Another source relates that Gracian was often invited to dinner by Philip III. He acquired fame as a preacher, although some of his oratorical displays, such as reading a letter sent from Hell from the pulpit, were frowned upon by his superiors. Eventually he was named Rector of the Jesuit college of Tarragona. He wrote several works proposing models for courtly conduct such as El héroe (The Hero) (1637), El político (The Politician), and El discreto (The Oneor “The Compleat Gentleman”) (1646). During the Spanish war with Catalonia and France, he was chaplain of the army that liberated Lleida in 1646.

In 1651, Gracian published the first part of the Criticón (Faultfinder) without the permission of his Jesuit superiors, whom he repeatedly disobeyed. This provoked the displeasure of he Order's authorities. Ignoring their reprimands, he published the third part of Criticón in 1657, and was sanctioned and exiled to Graus, where he tried unsuccessfully to leave the order. He died in 1658 and is buried in Tarazona near Zaragoza in the province of Aragon.

Thought and Works

Gracián wrote in a concentrated, terse style and is the most representative writer of the Spanish baroque literary style known as Conceptismo (Conceptism), of which he was the most important theoretician. Conceptismo is characterized by the use of terse and subtle displays of exaggerated wit to illustrate ideas. Gracian’s Agudeza y arte de ingenio (Wit and the Art of Inventiveness) (1643) was at once a poetic, a rhetoric and an anthology of the conceptist style.

Gracian’s earliest works, El héroe (1637) and El político (1640) were treatises on the ideal qualities for political leaders. His most famous book outside of Spain is Oráculo manual y arte de prudentia (1647), a collection of three hundred maxims, translated by Joseph Jacobs in 1892 as The Art of Wordly Wisdom. In contrast to Ignatius Loyola's Exercitia, which was a manual of prayer and devotion, Oráculo offered practical advice for social life.

The only one of his works which bears Gracián's name is El Comulgatorio (1655), a devotional work; his more important books were issued under the pseudonym of Lorenzo Gracián (a fictional brother of the writer) or under the anagram of Gracía de Marlones. In 1657 Gracián was punished by the Jesuit authorities for publishing El Criticón without his superior's permission, but they did not make any objection to the substance of the book.

Gracian influenced La Rochefoucauld, and later Voltaire, Nietzsche, and Schopenhauer, who considered Gracián's El criticón (3 parts, 1651–57) one of the best books ever written, and translated Oráculo manual y arte de prudential into German.

The Criticón

Criticón, an allegorical and pessimistic novel with philosophical overtones, was published in three parts in 1651, 1653, and 1657. It achieved fame in Europe, especially in the German-speaking countries, and was, without a doubt, the author's masterpiece and one of the great works of the Siglo de Oro. Criticón contrasted an idyllic primitive life with the evils of civilization. Its many vicissitudes, and the numerous adventures to which the characters are subjected, recalled the Byzantine style of novel; its satirical portrayal of society recalls the picaresque novel. A long pilgrimage is undertaken by the main characters, Critilo, the "critical man" who personifies disillusionment, and Andrenio, the "natural man" who represents innocence and primitive impulses. The author constantly uses a perspectivist technique to unfold the story according to the criteria or points of view of both characters, but in an antithetical rather than a plural way.

The following is a brief sketch of the Criticón, a complex work that demands detailed study: Critilo, man of the world, is shipwrecked on the coast of the island of Santa Elena, where he meets Andrenio, the natural man, who has grown up completely ignorant of civilization. Together they undertake a long voyage to the Isle of Immortality, travelling the long and prickly road of life. In the first part, "En la primavera de la niñez" ("In the Spring of Youth"), they join the royal court, where they suffer all manner of disappointments; in the second part, "En el otoño de la varonil edad" ("In the Autumn of the Age of Manliness"), they pass through Aragon, where they visit the house of Salastano (an anagram of the name of Gracián's friend Lastanosa), and travel to France, which the author calls the "wasteland of Hipocrinda," populated entirely by hypocrites and dunces, ending with a visit to a house of lunatics. In the third part, "En el invierno de la vejez" ("In the Winter of Old Age"), they arrive in Rome, where they encounter an academy where they meet the most inventive of men, arriving finally at the Isle of Immortality.

Defoe is alleged to have found the germ of his story Robinson Crusoe in El criticón.

The Art of Worldly Wisdom

Gracián's style, generically called "conceptism," is characterized by ellipsis (a rhetorical device in which the narrative skips over scenes) and the concentration of a maximum of meaning in a minimum of form, an approach referred to in Spanish as agudeza (wit). Gracian brought agudeza to its extreme in the Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia (literally The Oracle, a Manual of the Art of Discretion, commonly translated as The Art of Worldly Wisdom) (1637), which is almost entirely comprised of three hundred maxims with commentary. He constantly plays with words: each phrase becomes a puzzle, using the most diverse rhetorical devices.

- i Everything is already at its highest point (Todo está ya en su punto)

- iii Keep Matters for a Time in Suspense (Llevar sus cosas con suspencion)

- iv Knowledge and Courage (El saber y el valor)

- ix Avoid the Faults of your Nation (Desmentir los achaques de su nation)

- xi Cultivate those who can teach you (Tratar con quien se pueda aprender)

- xiii Act sometimes on Second Thoughts, sometimes on First Impulse (Obrar de intencion, ya segunda y ya primera)

- xxxvii Keep a Store of Sarcasms, and know how to use them (Conocer y saber usar de las varrillas)

- xliii Think with the Few and speak with the Many (Sentir con los menos y hablar con los mas)

- xcvii Obtain and preserve a Reputation (Conseguir y conservar la reputation)

- xxxvvv Think most about the things that matter most (Hazer concepto y mas de lo que importa mas)

Baltasar Gracián, Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia

Works

- El héroe (1637, The Hero), a criticism of Niccolò Machiavelli|Machiavelli drawing a portrait of the ideal Christian leader.

- El político Don Fernando el Católico (1640, The Politician King Ferdinand the Catholic), presents his ideal image of the politician.

- Arte de ingenio (1642, revised as Agudeza y arte de ingenio in 1648), an essay on literature and aesthetics.

- El discreto (1646, The Complete Gentleman), described the qualities which make the sophisticated man of the world.

- Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia (1647), translated as The Art of Worldly Wisdom (by Joseph Jacobs, 1892), The Oracle, a Manual of the Art of Discretion (by L.B. Walton), Practical Wisdom for Perilous Times (in selections by J. Leonard Kaye), or The Science of Success and the Art of Prudence, his most famous book, some 300 aphorisms with comments.

- El Criticón (1651-1657), a novel, translated as The Critic by Sir Paul Rycaut in 1681.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Foster, Virginia Ramos. 1975. Baltasar Gracián. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN: 080572396X 9780805723960 9780805723960 080572396X

- García Casanova, Juan Francisco, and José María Andreu Celma. 2003. El mundo de Baltasar Gracián: filosofía y literatura en el barroco. Granada [Spain]: Universidad de Granada. ISBN: 843382886X 9788433828866 9788433828866 843382886X

- Gracian, Baltasar, and Martin Fischer. 1993. The art of worldly wisdom: a collection of aphorisms from the work of Baltasar Gracian. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN: 1566191335 9781566191333 9781566191333 1566191335

- Hafter, Monroe Z. 1966. Gracián and perfection; Spanish moralists of the seventeenth century. Harvard studies in Romance languages, v. 30. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC: 346894

- Kassier, Theodore L. 1976. The truth disguised: allegorical structure and technique in Gracian's "Criticon". London: Tamesis. ISBN: 0729300064 : 9780729300063 9780729300063 0729300064

- Sánchez, Francisco J. 2003. An early bourgeois literature in golden age Spain: Lazarillo de Tormes, Guzmán de Alfarache and Baltasar Gracián. North Carolina studies in the Romance languages and literatures. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN: 0807892807 9780807892800 9780807892800 0807892807

- Spadaccini, Nicholas, and Jenaro Taléns. 1997. Rhetoric and politics: Baltasar Gracián and the new world order. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN: 0816629102 9780816629107 9780816629107 0816629102 0816629110 9780816629114 9780816629114 0816629110

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica in turn gives the following references: See Karl Borinski, Baltasar Gracián und die Hoflitteratur in Deutschland (Halle, 1894); Benedetto Croce, I Trattatisti Italiani del Concettismo e Baltasar Gracián (Napoli, 1899); Narciso José Lin y Heredia, Baltasar Gracián (Madrid, 1902). Schopenhauer and Joseph Jacobs have respectively translated the Oráculo manual into German and English.

External links

- Gracián, Baltasar in The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001.

- Baltasar Gracián biography and bibliography, from Books and Writers.

- "Gracián and the psychoanalysis", features a portrait.

- Translation of El Arte de Prudencia

- Balthasar Gracian's The Art of Worldly Wisdom

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.