Baba Yaga

Baba Yaga (Russian: Ба́ба-Яга́), is, in Slavic folklore, the wild old woman; the witch; and mistress of magic. She is also seen as a forest spirit, leading hosts of spirits. Stories about Baba Yaga have been used as a mediums in teaching to children the importance of reverance for the delicacy of nature and the spirit world. They were also used by worried parents in an attempt to frighten children from wondering far from home. Baba Yaga's legacy is derived from several Eastern European cultural groups and her character differs depending on who tells it but the outcome of the story usually emphasizes a purity of spirit and polite manners. [1]

Etymology

The name differs within the various Slavic languages. "Baba Yaga" is spelled "Baba Jaga" in Polish and as "Ježibaba" in [[Czech language|Czech] and Slovak. In Slovene, the words are reversed, producing Jaga Baba. The Russian is Бáба-Ягá; Bulgarian uses Баба Яга and Ukrainian, Баба Яґа; all of the last three are transliterated as Baba Yaga.

In South Slavic languages and traditions, there is a similar old witch: Baba Roga (Croatian and Bosnian), cyrillic equivalent Баба Рога (Macedonian and Serbian). The word Roga implies that she has horns.

The name of Baba Yaga is composed of two elements. Baba (originally a child's word) means an older or married woman of lower social class or simply grandmother in most Slavic languages. Yaga is a diminutive form of the Slavic name Jadwiga: (Jaga/Jagusia/Jadzia, etc.), although some etymologists conjecture other roots for the word. For example, Vasmer mentions the Proto-Slavic ęgа.

Folklore

In Russian tales, Baba Yaga is portrayed as a hag who flies through the air in a mortar, using the pestle as a rudder and sweeping away the tracks behind her with a broom made out of silver birch. She lives in a log cabin that moves around on a pair of dancing chicken legs. The keyhole to her front door is a mouth filled with sharp teeth; the fence outside is made with human bones with skulls on top — often with one pole lacking its skull, so there is space for the hero or heroes. In another legend, the house does not reveal the door until it is told a magical phrase: Turn your back to the forest, your front to me.[2]

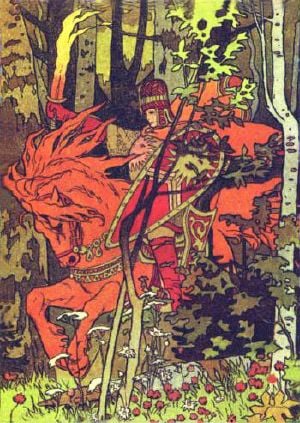

In some tales, her house is connected with three riders: one in white, riding a white horse with white harness, who is Day; a red rider, who is the Sun; and one in black, who is Night. She is served by invisible servants inside the house. She will explain about the riders if asked, but may kill a visitor who inquires about the servants. Baba Yaga is sometimes shown as an antagonist, and sometimes as a source of guidance; there are stories where she helps people with their quests, and stories in which she kidnaps children and threatens to eat them. Seeking out her aid is usually portrayed as a dangerous act. An emphasis is placed on the need for proper preparation and purity of spirit, as well as basic politeness.

In the folk tale Vasilissa the Beautiful, the young girl of the title is sent to visit Baba Yaga on an errand and is enslaved by her, but the hag's servants — a cat, a dog, a gate and a tree — help Vasilissa to escape because she has been kind to them. In the end, Baba Yaga is turned into a crow. Similarly, Prince Ivan in The Death of Koschei the Deathless is aided against her by animals whom he has spared.

In another version of the Vasilissa story recorded by Alexander Afanasyev (Narodnye russkie skazki, vol 4, 1862), Vasilissa is given three impossible tasks that she solves using a magic doll given to her by her mother.[1] Baba Yaga in Polish folklore differs in details. For example, the Polish Baba Jaga's house has only one chicken leg. Bad witches living in gingerbread houses are also commonly named Baba Jaga.

In some fairy tales, such as The Feather of Finist the Falcon, the hero meets not with one but three Baba Yagas. Such figures are usually benevolent, giving the hero advice or magical presents or both. [3]

Cabin on chicken legs

A "cabin on chicken legs with no windows and no doors" in which Baba Yaga dwells sounds like pure fantasy. In fact, this is an interpretation of an ordinary construction popular among hunter-nomadic peoples of Siberia of Uralic (Finno-Ugric) and Tungusic families, invented to preserve supplies against animals during long periods of absence. A doorless and windowless log cabin is built upon supports made from the stumps of two or three closely grown trees cut at the height of eight to ten feet. The stumps, with their spreading roots, give a good impression of "chicken legs." The only access into the cabin is via a trapdoor in the middle of the floor.

A similar but smaller construction was used by Siberian pagans to hold figurines of their gods. Recalling the late matriarchy among Siberian peoples, a common picture of a bone-carved doll in rags in a small cabin on top of a tree stump fits a common description of Baba Yaga, who barely fits her cabin with legs in one corner, head in another one, her nose grown into the ceiling. There are indications that ancient Slavs had a funeral tradition of cremation in huts of this type. In 1948 Russian archaeologists Yefimenko and Tretyakov discovered small huts of the described type with traces of corpse cremation and circular fences around them. . . [4]

Baba Yaga in Popular Culture

Film

Baba Yaga is a favorite subject of Russian films and cartoons. The animated film Bartok the Magnificent features Baba Yaga as a main character, but is not the antagonist. Indeed, the film Vasilissa the Beautiful by Aleksandr Rou, featuring Baba Yaga, was the first feature with fantasy elements in the Soviet Union, and the figure appeared often during the Soviet era.[5] In the Soviet era, she was interpreted as an exploiter of her animal servants.[6]

Literature

Baba Yaga is the primary antagonist in the fantasy novel Enchantment by Orson Scott Card, appears in the short story Joseph & Koza by Nobel Prize-winning writer Isaac Bashevis Singer and is regularly featured in stories in Jack and Jill, a popular children's magazine.[7]

Roleplaying games

Baba Yaga has made several appearances in the Dungeons & Dragons fantasy roleplaying game. Baba Yaga's hut is mentioned as an artifact in the first edition Dungeon Master's Guide (1979), by Gary Gygax.

Notes

- ↑ Ralston, W. Songs of the Russian People: Storyland Beings http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/srp. Retrieved September 15, 2007.

- ↑ Ralston, W.

- ↑ Ralston, W.

- ↑ Ефименко П. П., Третьяков П. Н. Курганный могильник у с. Боршева. МИА, № 8. М.; Л., 1948, рис. 37-42.)

- ↑ Graham, J., Baba Yaga in Film Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- ↑ Carter, A., 1990. The Old Wives' Fairy Tale Book, NY:Pantheon Books, p 239. ISBN 0-679-74037-6

- ↑ Jack and Jill Magazines Retrieved August 9, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Davidson, H. 2003. A Companion to the Fairy Tale. NY: D.S.Brewer. ISBN 0859917843.

Frierson, C. 1993. Peasant Icons: Representatives of Rural People in Late Nineteenth Century Russia. NY:Oxford Press. ISBN 0195872944.

Mamonova,T. 1989. Russian Women's Studies: Essays on Sexism in Soviet Culture. Oxford: Perganon Press. ISBN 080364829.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.