Babi Yar

| The Holocaust |

|---|

| Early elements |

| Racial policy · Nazi eugenics · Nuremberg Laws · Forced euthanasia · Concentration camps (list) |

| Jews |

| Jews in Nazi Germany, 1933 to 1939 |

|

Pogroms: Kristallnacht ¬∑ Bucharest ¬∑ Dorohoi ¬∑ IaŇüi ¬∑ Kaunas ¬∑ Jedwabne ¬∑ Lw√≥w |

|

Ghettos: Warsaw ¬∑ ŇĀ√≥dŇļ ¬∑ Lw√≥w ¬∑ Krak√≥w ¬∑ Theresienstadt ¬∑ Kovno ¬∑ Wilno |

|

Einsatzgruppen: Babi Yar · Rumbula · Ponary · Odessa |

|

Final Solution: Wannsee · Aktion Reinhard |

|

Extermination camps: Auschwitz ¬∑ Belzec ¬∑ CheŇāmno ¬∑ Majdanek ¬∑ Sobib√≥r ¬∑ Treblinka |

|

Resistance: Jewish partisans · Ghetto uprisings (Warsaw) |

|

End of World War II: Death marches · Berihah · Displaced persons |

| Other victims |

|

East Slavs · Poles · Roma · Homosexuals |

| Responsible parties |

|

Nazi Germany: Hitler · Eichmann · Heydrich · Himmler · SS · Gestapo · SA Aftermath: Nuremberg Trials · Denazification |

| Lists |

| Survivors · Victims · Rescuers |

| Resources |

| The Destruction of the European Jews Phases of the Holocaust Functionalism vs. intentionalism |

Babi Yar (Ukrainian: –Ď–į–Ī–ł–Ĺ —Ź—Ä, Babyn yar; Russian: –Ď–į–Ī–ł–Ļ —Ź—Ä, Babiy yar) is a ravine in Kiev, the capital of Ukraine, located between the Frunze and Melnykov streets and between the Saint Cyril's Monastery and Olena Teliha Street.

The ravine was first noted in historical records during the early fifteenth century, but is remembered today as the site where more than 100,000 Soviet civilians, of whom a significant number were Jews, were executed by the Nazis during the Second World War.

On September 29-30, 1941 at least 33,771 Jewish civilians were murdered. This two-day massacre of was one of the largest single mass killings of the Holocaust.[1][2], second only to the Romanian extermination of more than 40,000 Jews in Bogdanovka in 1941. In the months that followed, many more thousands of Jews were seized, taken to Babi Yar, and shot.[3]

Historical background

The Babi Yar ravine was first mentioned in 1401, in connection with its sale by "baba" (a woman), the cantiniere, to the Dominican Monastery.[4] In the course of several centuries the site had been used for different purposes including military camps and at least two cemeteries, among them a New Jewish Cemetery that had been closed by 1937.

World War II

After the 45-day battle for the city of Kiev, Nazi forces finally entered the city on September 19, 1941. The first executions took place on September 27, 1941, when 700 patients were removed from the local psychiatric hospital and executed.

The massacres of September 29-30, 1941

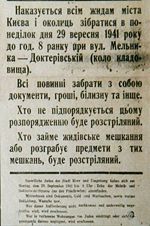

On September 28, notices were posted in Kiev which stated:

"It is ordered that all Jews living in the city of Kiev and its environs are to report on the morning of Monday, September 29, 1941, by eight o'clock to the corner of Melnyk (sic) and Dokterivsky Streets (near the cemetery). They are to take with them documents, money, underwear, etc. All who do not heed these instruction will be shot. Anyone entering apartments evacuated by Jews and stealing property from those apartments will be shot."

The Jews of Kiev gathered by the cemetery, expecting to be loaded onto trains. The crowd was large enough that most of the men, women, and children could not have known what was happening until it was too late: by the time they heard the machine-gun fire, there was no chance to escape. All were driven down a corridor of soldiers, in groups of ten, and then shot. Anatoly Kuznetsov described the massacre:

"There was no question of being able to dodge or get away. Brutal blows, immediately drawing blood, descended on their heads, backs and shoulders from left and right. The soldiers kept shouting: "Schnell, schnell!" laughing happily, as if they were watching a circus act; they even found ways of delivering harder blows in the more vulnerable places, the ribs, the stomach and the groin."

The Jews were then ordered to undress, beaten if they resisted, and then shot at the edge of the Babi Yar gorge. According to the Einsatzgruppen Operational Situation Report No. 101,[5] 33,771 Jews from Kiev and its suburbs were systematically shot dead by machine-gun fire at Babi Yar on September 29 and September 30, 1941.

A unit of Einsatzgruppe C, Police Battalion 45 commanded by a Major Besser, carried out the massacre, supported by members of a Waffen-SS battalion. Units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police, under the general command of Friedrich Jeckeln were used to round up and direct the Jews to the location.

Further executions

Further executions took place on October 1, 2, 8, and 11, 1941. During this time another 17,000 more Jews were executed. Mass executions in the ravine continued up until Germans withdrew from the city in 1943.

Estimates of the total number of dead at Babi Yar during the Nazi occupation vary. The Soviet estimation stated that there were approximately 100,000 corpses lying in Babi Yar.[2] Some put the number as low as 70,000; others as high as 200,000. According to testimonies of Jewish workers forced to burn the bodies, the numbers range from 70,000 to 120,000.

Later in Babi Yar, the Syretsk Concentration Camp was set up, where interned communists, Soviet POWs, and captured resistance fighters were executed. On February 18, 1943 three Dynamo Kyiv players, who took part in the Match of Death with German Luftwaffe team were executed in the camp. It is estimated that around 25,000 people died in the camp.

Cover-up attempts

With the Nazi retreat from Kiev, attempts were made to cover up the atrocities committed at Babi Yar and the surrounding areas. From August to September of 1943, the Syretsk camp was partially destroyed and some of the corpses were exhumed and burned; their ashes were scattered in the vicinity. During the night of September 29, 1943, as the camp was being dismantled, an inmate revolt broke out, and 15 people escaped. Once control was re-established in the camp, the remaining 311 inmates were executed.

Remembrance

When the Red Army took control of the city on November 6, 1943, the Syretsk Concentration Camp was converted into a Soviet internment camp for German POWs and operated until 1946. The camp was subsequently demolished and in the 1950s and 1960s urban development began in the area that included an apartment complex and a park. The construction of a dam nearby also saw the ravine filled with industrial pulp. (The dam collapsed in 1961, leading to a mudslide with numerous fatalities.)

Soviet leadership minimized the emphasis on the Jewish aspect of this tragedy; instead, they sought to present these events as crimes committed against the entire Soviet people and the inhabitants of Kiev. This not only served Soviet propaganda purposed, but may have also revealed the Soviet state's own anti-semitic tendencies. Several attempts were made to build a memorial at Babi Yar to commemorate the fate of the Jewish victims, but all attempts were overruled. An official memorial for the Soviet citizens shot at Babi Yar was erected in 1976. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 a memorial for the Jewish victims was finally placed at Babi Yar.

Artistic Commemorations of Babi Yar

The massacre of Jews at Babi Yar has inspired a number of different artistic representations. A poem by the same name was written by the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko; his poem was originally circulated in samizdat. It could not be published in the Soviet press until 1984. It was enthusiastically set to music by Dmitri Shostakovich in his Symphony No. 13. An oratorio was composed by the Ukrainian composer Yevhen Stankovych to the text of Dmytro Pavlychko (2006). A number of films and television productions were made to mark the tragic events at Babi Yar.

Concerning Babi Yar, Elie Wiesel stated: "Eyewitnesses say that for months after the killings the ground continued to spurt geysers of blood." [6]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Holocaust Encyclopedia. Kiev and Babi Yar

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 Israel Gutman, editor-in-chief, Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust, Babi Yar, New York: Macmillan, 1990. 4 volumes. ISBN 0028960904.

- ‚ÜĎ Babi Yar. Extracts from the Article by Shmuel Spector, Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Israel Gutman, editor in Chief, Yad Vashem, Sifriat Hapoalim, MacMillan Publishing Company, 1990.

- ‚ÜĎ Anatoliy Kudrytsky, editor-in-chiev, "Vulytsi Kyjeva" (The Streets of Kiev), Ukrainska Entsyklopediya (1995), ISBN 5885000700

- ‚ÜĎ "Operational Situation Report No. 101" The Einsatzgruppen. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Boston University Chancellor Responds to Holocaust Deniers' Ads in Campus Papers Open letter from Dr. John Silber to Colleges and Universities. March 2000. (Jewish Virtual Library)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gutman, Israel, editor-in-chief, Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust, Babi Yar, New York: Macmillan, 1990. 4 volumes. ISBN 0028960904

- Kuznetsov, Anatoli A., Babi Yar, Translated by David Floyd, Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1970. ISBN 0671451359

- Encyclopedia of Kyiv](in Ukrainian)

External links

All links retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Babi Yar: Mass Murder (history1900s.about.com)

- The Massacre at Babi Yar Near Kyiv (historyplace.com)

- Babi Yar: Killing Ravine of Kiev Jewry ‚Äď WWII (zchor.org)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.