Difference between revisions of "Innovation" - New World Encyclopedia

MaedaMartha (talk | contribs) (New page: {{otheruses}} {{Nofootnotes|date=November 2007}} right|thumb|250px|A personification of innovation as represented by a [[statue in The American Adventure in t...) |

MaedaMartha (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[Image:Innovation.JPG|right|thumb|250px|A personification of innovation as represented by a [[statue]] in [[The American Adventure]] in the World Showcase pavilion of [[Walt Disney World]]'s [[Epcot]].]] | ||

| + | The term '''innovation''' means “the introduction of something new,” or “a new idea, method or device.” Innovation characteristically involves [[creativity]], but is not synonymous with it. Innovation is distinct from invention and involves the actual implementation of a new idea or process in society. Innovation is an important topic in the study of [[economics]], [[history]], [[business]], [[technology]], [[sociology]], [[policy making]] and [[engineering]]. Historians, sociologists and anthropologists study the events and circumstances leading up to innovations and the changes they bring about in human society. Social and economic innovations often occur spontaneously, as human beings respond in a natural way to new circumstances. Since innovation is believed to drive economic growth, knowledge of the factors that lead to innovation is critical to [[policy]] makers. | ||

| − | + | In organizations and businesses, innovation is linked to performance and growth through improvements in efficiency, [[productivity]], [[quality]], and [[competitive positioning]]. | |

| − | + | Businesses actively seek to innovate in order to increase their market share and ensure their growth. A successful innovation does not always bring about the desired results and may have negative consequences. A number of economic theories, mathematical formulas, management strategies and computer business models are used to forecast the outcome of an innovation. Innovation leading to increased productivity is the fundamental source of increasing wealth in an economy. Various indices, such as expenditure on research, and factors such as availability of capital, human capacity, infrastructure, and technological sophistication are used to measure how conducive a nation is to fostering innovation. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Innovation is an important topic in the study of [[economics]], [[business]], [[technology]], [[sociology]], and [[engineering]]. | + | ==The concept of innovation== |

| + | The term “innovation” dates from the 15th century and means “the introduction of something new,” or “a new idea, method or device.”<ref>[http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/innovation “innovation”] Merriam Webster. Retrieved February 9, 2009.</ref>. In its modern usage, a distinction is typically made between an idea, an invention (an idea made manifest), and innovation (ideas applied successfully). <ref>Max Mckeown, The Truth About Innovation. Pearson / Financial Times. 2008. ISBN 0273719122 </ref>. Innovation is an important topic in the study of [[economics]], [[business]], [[technology]], [[sociology]], [[policy making]] and [[engineering]]. In each of these fields “innovation” connotes something slightly different. | ||

| − | + | Innovation has been studied in a variety of contexts, and scholars have developed a wide range of approaches to defining and measuring innovation. A consistent theme in discussions of innovation is the understanding that it is the successful ''introduction'' of something ''new'' and ''useful'', for example introducing new methods, techniques, or practices or new or altered products and services.<ref name=fag> Jan Fagerberg, "Innovation: A Guide to the Literature" in Fagerberg, Jan, David C. Mowery and Richard R. Nelson. The Oxford Handbook of Innovations. Oxford University Press. 2004. pp. 1–26. ISBN 0–19–926455–4.</ref> Though innovation is frequently associated with improvement and thought of as being positive and beneficial, the successful introduction of a “new” and “useful” method, practice or product may have negative consequences for an organization or society, such as the disruption of traditional social relationships or the obsolescence of certain labor skills. A “useful” new product may have a negative impact on the environment, or may bring about the depletion of natural resources. | |

| − | == | + | ==Innovation, creativity and invention== |

| − | + | [[Invention]], the creation of new forms, compositions of matter, or processes, is often confused with innovation. An invention is the first occurrence of an idea for a new product or process, while innovation involves implementing its use in society. <ref name=fag/>The electric light bulb did not become an innovation until Thomas Edison established power plants to furnish electricity to streetlamps and houses so that the light bulbs could be used. In an organization, an idea, a change or an improvement is only an innovation when it is implemented and effectively causes a social or commercial reorganization. | |

| − | + | Innovation characteristically involves [[creativity]], but is not synonymous with it. A creative idea or insight is only the beginning of innovation; innovation involves acting on the creative idea to bring about some specific and tangible difference. For example, in a business or organization, innovation does not occur until a creative insight or idea results in new or altered business processes within the organization, or changes in the products and services provided. | |

| − | == | + | ==Sociology, history, behavioral sciences== |

| + | Historians, sociologists and anthropologists study the events and circumstances leading up to innovations and the changes they bring about in human society. One of the greatest innovations in human history was the Industrial Revolution, which ended feudalism, led to the establishment of huge urban centers, and put power in the hands of businessmen. The concentration of large numbers of people in cities and towns and the rise of a middle class resulted in innovations in housing, public health, education, and the arts and entertainment. The Industrial Revolution itself was the result of myriads of innovations in technology, social organization, and banking and finance. The establishment of a democratic government in the United States in 1776 was an innovation that had far-reaching consequences for European countries and eventually for the rest of the world. | ||

| − | + | The development of modern forms of transportation, the train, automobile, and airplane, also altered the way in which people live and conduct business. Innovations in weaponry, such as the cannon and musket, and more recently, guided missiles and nuclear bombs, gave the nations who implemented them dominance over other nations. | |

| − | + | During the last decade of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century, technological innovations like the cell phone, internet and wireless technology transformed the way in which people communicate with each other and gain access to information. Cell phones have made it possible for people in developing countries, who previously did not have access to an efficient telephone system, to communicate freely and easily, facilitating business transactions and social relationships. The internet allows people in countries where governmental control or inadequate economic resources limit access to information, to circumvent those restrictions and disseminate knowledge internationally. Individuals now have immediate access to information about the stock market, their bank accounts, current events, the weather, and consumer products. | |

| − | + | ==Policy making== | |

| − | === | + | Social and economic innovations often occur spontaneously, as human beings respond in a natural way to new circumstances. Governments, legislators, urban planners and administrators are concerned with bringing about deliberate innovation through creating and implementing effective public policies to achieve certain goals. The cost of enforcing a new public policy must be weighed against the expected benefits. A policy change may have unforeseen, and sometimes unwanted, consequences. |

| − | + | Examples of public policies that have brought about positive social innovations are the granting of property rights to women, universal suffrage, welfare and unemployment compensation and mandatory education for children. Examples of public policy that resulted in harmful innovation are the Cultural Revolution initiated in 1966 by Mao Zedong, which closed universities and suppressed education for several years in China; the collectivization of agriculture in the U.S.S.R. by Joseph Stalin <ref>Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives. London: HarperCollins, 1991 (hardcover, ISBN 0002154943); New York: Vintage Books, 1993 (paperback, ISBN 0679729941). p. 269</ref> which caused millions to die of starvation during 1931 and 1932; and the efforts of Pol Pot (Saloth Sar) in the 1970s to evacuate all urban dwellers to the countryside and return to an agricultural barter economy, which cost the lives of approximately 26 percent of Cambodia’s population. <ref name = yale>{{cite web|url=http://www.yale.edu/cgp/ |title=The Cambodian Genocide Program |accessdate= Retrieved February 10, 2009|date= 1994-2008 |work= Genocide Studies Program |publisher= [[Yale University]] }}</ref> | |

| − | + | == Organizations == | |

| + | In the context of an organization such as a corporation, local government, hospital, university, or non-profit organization, innovation is linked to performance and growth through improvements in efficiency, [[productivity]], [[quality]], and [[competitive positioning]]. A new management procedure, organizational structure, method of operation, communications device or product may be introduced in an effort to make the organization more efficient and productive. Successful innovation requires the definition of goals, knowledge of the materials and processes involved, financial and human resources, and effective management. A certain amount of experimentation is also necessary to adjust the new processes so that they produce the desired result. | ||

| − | + | Deliberate innovation involves risk. Organizations that do not innovate effectively may be destroyed by those that do. While innovation typically adds value, it may also have a negative or destructive effect as new developments clear away or change old organizational forms and practices. If the changes undermine employee morale, the new system may be less efficient than the old. Innovation can also be costly. The expense of purchasing and installing new equipment, computers and software, or of re-organizing, hiring and training staff is substantial, and may leave an organization without sufficient resources to continue its operations effectively. Organizations attempt to minimize risk by studying and analyzing innovations carried out by other organizations, by employing experts and consultants to carry out the innovation, and by following a number of formulas and management strategies. | |

| − | + | The introduction of computers during the second half of the 20th century necessitated innovation in almost every type of organization. The productivity of individual workers was increased, and many clerical jobs were eliminated. Organizations made large investments in technology and created entire departments to maintain and manage computers and information, giving rise to a number of new professions. Paper documents were translated into electronic data. The workforce acquired new skills, and those who could not adapt dropped behind younger workers who were more familiar with technology and changed the dynamics of the workplace. Networks and internet connections allowed frequent and rapid communication within an organization. The centralization of information such as inventory, financial accounts and medical records made new types of analysis and measurement possible. While organizations benefited in many ways from the new technology, the expense and risk of innovating also increased. | |

| − | + | == Economics and business == | |

| + | The study and understanding of innovation is particularly important in the fields of business and economics because it is believed that innovation directly drives economic growth. The ability to innovate translates into new goods and services and entry into new markets, and results in increased sales. An increase in sales contributes to the prosperity of the workforce and increases its purchasing power, leading to a steady expansion of the economy. | ||

| − | : | + | In 1934, the European economist [[Joseph Schumpeter]] (1883 – 1955) defined economic innovation as: |

| + | #The introduction of a new good — that is one with which consumers are not yet familiar — or of a new quality of a good. | ||

| + | #The introduction of a new method of production, which need by no means be founded upon a discovery scientifically new, and can also exist in a new way of handling a commodity commercially. | ||

| + | #The opening of a new market, that is a market into which the particular branch of manufacture of the country in question has not previously entered, whether or not this market has existed before. | ||

| + | #The conquest of a new source of supply of raw materials or half-manufactured goods, again irrespective of whether this source already exists or whether it has first to be created. | ||

| + | #The carrying out of the new organization of any industry, like the creation of a monopoly position (for example through trustification) or the breaking up of a monopoly position'':.<ref>{{cite book | ||

| + | | last = Schumpeter | ||

| + | | first = Joseph | ||

| + | | authorlink = Joseph Schumpete | ||

| + | | year = 1934 | ||

| + | | title = The Theory of Economic Development | ||

| + | | publisher = Harvard University Press, Boston | ||

| − | + | }}</ref> | |

| − | :'' | + | Businesses recognize that innovation is essential for their survival, and seek to create a business model that fosters innovation while controlling costs<ref> Davila, Tony; Marc J. Epstein and Robert Shelton Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It''. Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing. 2006. ISBN 0–13–149786–3 p. 6</ref>. Managers use mathematical formulas, behavioral studies and forecasting models to create strategies for implementing innovation. Business organizations spend between ½ of a percent (for organizations with a low rate of change) to more than 20 percent of their annual revenue on making changes to their established products, processes and services. The average investment across all types of organizations is four percent, spread across functions including marketing, product design, information systems, manufacturing systems and quality assurance. |

| − | + | Much of the innovation carried out by business organizations is not directed towards development of new products, but towards other goals such as reduction of materials and labor costs, improvement of quality, expansion of existing product lines, creation of new markets, reduction of energy consumption and lessening of environmental impact. | |

| − | + | Many "breakthrough innovations" are the result of formal [[research and development]], but innovations may be developed by less formal on-the-job modifications of practice, or through the exchange and combination of professional experience. | |

| − | + | The traditionally recognized source of innovation is ''manufacturer innovation,'' where a person or business innovates in order to sell the innovation. Another important source of innovation is ''end-user innovation,'' in which a person or company develops an innovation for their own use because existing products do not meet their needs. <ref>{{cite book | |

| + | | last = von Hippel | ||

| + | | first = Eric | ||

| + | | authorlink = Eric von Hippel | ||

| + | | year = 1988 | ||

| + | | title = [http://web.mit.edu/evhippel/www/books/sources/SofI.pdf The Sources of Innovation] Retrieved February 10, 2009 | ||

| + | | publisher = Oxford University Press | ||

| + | | id = ISBN 0–19–509422–0 | ||

| + | }}</ref> User innovators may become [[entrepreneur]]s selling their product, or more commonly, trade their innovation in exchange for other innovations or services. In the case of computer software, they may choose to freely share their innovations, using methods like [[open source]]. In such [[Networks of Innovation|networks of innovation]] the creativity of the users or communities of users can further develop technologies and their use. | ||

| − | + | Analysts debate whether innovation is mainly [[supply-pushed]] (based on new technological possibilities) or [[demand-led]] (based on social needs and market requirements). They also continue to discuss what exactly drives innovation in organizations and economies. Recent studies have revealed that innovation does not just happen within the industrial supply-side, or as a result of the articulation of user demand, but through a complex set of processes that links input from not only developers and users, but a wide variety of intermediary organizations such as consultancies and standards associations. Examination of social networks suggests that much successful innovation occurs at the boundaries of organizations and industries where the problems and needs of users, and the potential of technologies are together in a creative process. | |

| − | + | == Diffusion of innovations == | |

| − | + | [[Image:InnovationLifeCycle.jpg|300px|right]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

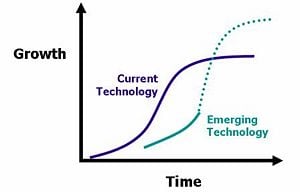

| − | + | Once innovation occurs, innovations may be spread from the innovator to other individuals and groups. In 1962, [[Everett Rogers]] proposed that the life cycle of innovations can be described using the ‘s-curve’ or [[Diffusion of innovations|diffusion curve]]. The s-curve maps growth of revenue or productivity against time. In the early stage of a particular innovation, growth is relatively slow as the new product establishes itself. At some point consumer demand increases and product sales expand more rapidly. New incremental innovations or changes to the product allow growth to continue. Towards the end of its life cycle growth slows and may even begin to decline. In the later stages, no amount of new investment in that product will yield a normal rate of return. | |

| − | |||

| − | '' | + | Innovative companies will typically be constantly working on new innovations that will eventually replace older ones. Successive s-curves will come along to replace older ones and continue to drive growth upwards. In the figure above the first curve shows a current technology. The second shows an [[emerging technologies|emerging technology]] that currently yields lower growth but will eventually overtake the current technology and lead to even greater levels of growth. The length of life will depend on many factors. |

| + | <ref>Rogers, Everett M. (2003).''Diffusion of Innovations'', 5th ed.. New York, NY: Free Press.</ref> | ||

| − | + | [[image:Bass diffusion model.gif|right]] | |

| − | + | The ''Bass diffusion model'' developed by [[Frank Bass]] in 1969 illustrates the process by which a new innovative product is adopted by new users, then is overtaken by products imitating the innovation. The model is widely used in [[forecasting]], especially [[product forecasting]] and [[technology forecasting]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Schumpeter's focus on innovation is reflected in Neo-Schumpeterian economics, developed by such scholars as [[Christopher Freeman]]<ref>{{cite book | Schumpeter's focus on innovation is reflected in Neo-Schumpeterian economics, developed by such scholars as [[Christopher Freeman]]<ref>{{cite book | ||

| Line 106: | Line 110: | ||

''' | ''' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Failure of innovation == | == Failure of innovation == | ||

| − | Research | + | Success in implementing an innovation does not guarantee a beneficial outcome. Research shows that from fifty to ninety percent of innovation projects are judged to have made little or no contribution to the goals of the innovating organization. Innovations that fail are often potentially ‘good’ ideas but do not achieve desired results because of budgetary constraints, lack of skills, poor leadership, lack of knowledge, lack of motivation, or poor fit with current goals. The impact of failure goes beyond the simple loss of investment. Failure can also lead to loss of morale among employees, an increase in cynicism and even higher resistance to change in the future. Most companies allow for the possibility of failure when planning an innovation, and include processes for detecting problems before they consume too many resources and threaten the organization’s future. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Early detection of problems and adjustment of the innovation process contribute to the success of the final outcome. The lessons learned from failure often reside longer in the organizational consciousness than lessons learned from success. | |

== Measures of innovation == | == Measures of innovation == | ||

| − | + | Attempts to measure innovation take place on two levels: the organizational level and the political level. Within an organization, innovation can be evaluated by conducting surveys and workshops, consulting outside experts, or using internal benchmarks. There is no measure of organizational innovation. Corporate measurements generally utilize scorecards which cover several aspects of innovation such as financial data, innovation process efficiency, employees' contribution and motivation, and benefits for customers. The elements selected for these evaluations vary widely from company to company and may include new product revenue, amount spent on research and development, time to market, customer and employee perception and satisfaction, number of patents, and additional sales resulting from past innovations. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The Oslo Manual | + | On a political level, measures of innovation are used to compare one country or region with another. The OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ) Oslo Manual of 1995 suggested standard guidelines for measuring technological product and process innovation. The new Oslo Manual of 2005 added marketing and organizational innovation. The [[Bogota Manual]] was created in 2001 for Latin America and the Caribbean countries. A traditional indicator used to measure innovation is expenditure, for example, investment in R&D (Research and Development) as a percentage of GNP (Gross National Product). |

| − | + | Economists Christopher Freeman''' (born 1921) and Bengt-Åke Lundvall developed the National Innovation System (NIS) to explain the flow of technology and information which is key to the innovative process on the national level. According to [[innovation system|innovation system theory]], [[innovation]] and technology development are results of a complex set of relationships among people, enterprises, universities and government research institutes. | |

| − | + | The 2008-2009 Global Innovation Index created by Soumitra Dutta, a professor at French business school INSEAD, along with New Delhi based non-profit organization The Confederation of Indian Industry <ref>[http://www.fastcompany.com/blog/saabira-chaudhuri/itinerant-mind/united-states-worlds-number-one-innovator United States The World's Number One Innovator?] Saabira Chaudhuri, Fast Company (January 7, 2009) Retrieved February 9, 2009.</ref> ranks nations based on indices such as the number of internet users in a nation, the ease of doing business and the stability of banks. Every factor is then categorized as either an input or an output. Inputs indicate how conducive countries are to fostering innovation, and include institutions and policies, human capacity, infrastructure, technological sophistication, business markets and capital. The outputs indicate how effectively countries translate innovation into benefits such as knowledge, competitiveness and wealth. The top ten countries are listed below: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

{| class="sortable wikitable" | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| Line 274: | Line 151: | ||

| 10 || {{flag|Netherlands}} || [[Europe]] | | 10 || {{flag|Netherlands}} || [[Europe]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 282: | Line 156: | ||

* [[Creative problem solving]] | * [[Creative problem solving]] | ||

* [[Theories of technology]] | * [[Theories of technology]] | ||

| − | |||

* [[Diffusion (anthropology)]] | * [[Diffusion (anthropology)]] | ||

* [[Ecoinnovation]] | * [[Ecoinnovation]] | ||

* [[Emerging technologies]] | * [[Emerging technologies]] | ||

| − | |||

* [[Hype cycle]] | * [[Hype cycle]] | ||

* [[Individual capital]] | * [[Individual capital]] | ||

| − | |||

* [[Information revolution]] | * [[Information revolution]] | ||

* [[Ingenuity]] | * [[Ingenuity]] | ||

* [[Invention]] | * [[Invention]] | ||

| − | |||

* [[Innovation Economics]] | * [[Innovation Economics]] | ||

* [[Open Innovation]] | * [[Open Innovation]] | ||

| Line 300: | Line 170: | ||

* [[Research]] | * [[Research]] | ||

* [[Timeline of invention]] | * [[Timeline of invention]] | ||

| − | |||

* [[User innovation]] | * [[User innovation]] | ||

* [[Value network]] | * [[Value network]] | ||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references /> | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | * | + | *Barras, R. "Towards a theory of innovation in services". Research Policy 15: 161–73. 1984. |

| − | + | *Cabral, Regis. "Development, Science and". in Heilbron, J.. The Oxford Companion to The History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. 2003. pp. 205–207. | |

| − | + | *Chakravorti, Bhaskar. The Slow Pace of Fast Change: Bringing Innovations to Market in a Connected World. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 2003. | |

| − | + | *Byrd, Jacqueline. The Innovation Equation - Building Creativity & Risk Taking in your Organization. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer - Aprint. 2003. ISBN 0-7879-6250-3. | |

| − | + | *Chesbrough, Henry William. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 2003. ISBN 1–57851–837–7. | |

| − | + | *Christensen, Clayton M. . The Innovator's Dilemma. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 1997. ISBN 0–06–052199–6. | |

| − | + | *Davila, Tony; Marc J. Epstein and Robert Shelton. Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It''. Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing. 2006. ISBN 0–13–149786–3. | |

| − | + | *Ettlie, John. Managing Innovation, Second Edition. Butterworth-Heineman, an imprint of Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 0–7506–7895-X. | |

| − | + | *Fagerberg, Jan. "Innovation: A Guide to the Literature". in Fagerberg, Jan, David C. Mowery and Richard R. Nelson. The Oxford Handbook of Innovations. Oxford University Press. 2004. pp. 1–26. ISBN 0–19–926455–4. | |

| − | * | + | *Freeman, Chris. The Economics of Industrial Innovation. Frances Pinter, London. 1982. |

| − | + | *Hesselbein, Frances, Marshall Goldsmith, and Iain Sommerville, ed (2002). Leading for Innovation: And organizing for results. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0–7879–5359–8. | |

| − | + | *Hitcher, Waldo. Innovation Paradigm Replaced. Wiley. 2006. | |

| − | + | *Luecke, Richard; Ralph Katz. Managing Creativity and Innovation. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 2003. ISBN 1–59139–112–1. | |

| − | + | *Mckeown, Max. The Truth About Innovation. Pearson / Financial Times. 2008. ISBN 0273719122. | |

| − | + | *Miles, Ian. "Innovation in Services". in Fagerberg, Jan, David C. Mowery and Richard R. Nelson. The Oxford Handbook of Innovations. Oxford University Press. 2004. pp. 433–458. ISBN 0–19–926455–4. | |

| − | + | *OECD The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities. Proposed Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Technological Innovation Data. Oslo Manual. 2nd edition, DSTI, OECD / European Commission Eurostat, Paris 31 Dec 1995. | |

| − | + | *Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of Innovation. New York, NY: Free Press. 1962. | |

| − | + | *Rosenberg, Nathan Perspectives on Technology. Cambridge, London and N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. 1975. | |

| − | + | *Schumpeter, Joseph. The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1934. | |

| − | + | *Scotchmer, Suzanne. Innovation and Incentives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2004. | |

| − | + | *Stein, Morris. Stimulating creativity. New York: Academic Press. 1974. | |

| − | + | *von Hippel, Eric . Democratizing Innovation. 2005. MIT Press. ISBN 0–262–22074–1. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *OECD | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved February 11, 2009. | |

| − | |||

* Academic article on [http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=964672 Being a Systems Innovator] on SSRN | * Academic article on [http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=964672 Being a Systems Innovator] on SSRN | ||

*[http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/innovation/communication.htm "Communication on Innovation policy: updating the Union’s approach in the context of the Lisbon strategy"] – The [[European Commission]]. | *[http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/innovation/communication.htm "Communication on Innovation policy: updating the Union’s approach in the context of the Lisbon strategy"] – The [[European Commission]]. | ||

| Line 658: | Line 210: | ||

[[Category:Science and technology studies]] | [[Category:Science and technology studies]] | ||

[[Category:Economics]] | [[Category:Economics]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

{{credits|Innovation|269731888|}} | {{credits|Innovation|269731888|}} | ||

Revision as of 19:37, 11 February 2009

The term innovation means “the introduction of something new,” or “a new idea, method or device.” Innovation characteristically involves creativity, but is not synonymous with it. Innovation is distinct from invention and involves the actual implementation of a new idea or process in society. Innovation is an important topic in the study of economics, history, business, technology, sociology, policy making and engineering. Historians, sociologists and anthropologists study the events and circumstances leading up to innovations and the changes they bring about in human society. Social and economic innovations often occur spontaneously, as human beings respond in a natural way to new circumstances. Since innovation is believed to drive economic growth, knowledge of the factors that lead to innovation is critical to policy makers.

In organizations and businesses, innovation is linked to performance and growth through improvements in efficiency, productivity, quality, and competitive positioning. Businesses actively seek to innovate in order to increase their market share and ensure their growth. A successful innovation does not always bring about the desired results and may have negative consequences. A number of economic theories, mathematical formulas, management strategies and computer business models are used to forecast the outcome of an innovation. Innovation leading to increased productivity is the fundamental source of increasing wealth in an economy. Various indices, such as expenditure on research, and factors such as availability of capital, human capacity, infrastructure, and technological sophistication are used to measure how conducive a nation is to fostering innovation.

The concept of innovation

The term “innovation” dates from the 15th century and means “the introduction of something new,” or “a new idea, method or device.”[1]. In its modern usage, a distinction is typically made between an idea, an invention (an idea made manifest), and innovation (ideas applied successfully). [2]. Innovation is an important topic in the study of economics, business, technology, sociology, policy making and engineering. In each of these fields “innovation” connotes something slightly different.

Innovation has been studied in a variety of contexts, and scholars have developed a wide range of approaches to defining and measuring innovation. A consistent theme in discussions of innovation is the understanding that it is the successful introduction of something new and useful, for example introducing new methods, techniques, or practices or new or altered products and services.[3] Though innovation is frequently associated with improvement and thought of as being positive and beneficial, the successful introduction of a “new” and “useful” method, practice or product may have negative consequences for an organization or society, such as the disruption of traditional social relationships or the obsolescence of certain labor skills. A “useful” new product may have a negative impact on the environment, or may bring about the depletion of natural resources.

Innovation, creativity and invention

Invention, the creation of new forms, compositions of matter, or processes, is often confused with innovation. An invention is the first occurrence of an idea for a new product or process, while innovation involves implementing its use in society. [3]The electric light bulb did not become an innovation until Thomas Edison established power plants to furnish electricity to streetlamps and houses so that the light bulbs could be used. In an organization, an idea, a change or an improvement is only an innovation when it is implemented and effectively causes a social or commercial reorganization.

Innovation characteristically involves creativity, but is not synonymous with it. A creative idea or insight is only the beginning of innovation; innovation involves acting on the creative idea to bring about some specific and tangible difference. For example, in a business or organization, innovation does not occur until a creative insight or idea results in new or altered business processes within the organization, or changes in the products and services provided.

Sociology, history, behavioral sciences

Historians, sociologists and anthropologists study the events and circumstances leading up to innovations and the changes they bring about in human society. One of the greatest innovations in human history was the Industrial Revolution, which ended feudalism, led to the establishment of huge urban centers, and put power in the hands of businessmen. The concentration of large numbers of people in cities and towns and the rise of a middle class resulted in innovations in housing, public health, education, and the arts and entertainment. The Industrial Revolution itself was the result of myriads of innovations in technology, social organization, and banking and finance. The establishment of a democratic government in the United States in 1776 was an innovation that had far-reaching consequences for European countries and eventually for the rest of the world.

The development of modern forms of transportation, the train, automobile, and airplane, also altered the way in which people live and conduct business. Innovations in weaponry, such as the cannon and musket, and more recently, guided missiles and nuclear bombs, gave the nations who implemented them dominance over other nations.

During the last decade of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century, technological innovations like the cell phone, internet and wireless technology transformed the way in which people communicate with each other and gain access to information. Cell phones have made it possible for people in developing countries, who previously did not have access to an efficient telephone system, to communicate freely and easily, facilitating business transactions and social relationships. The internet allows people in countries where governmental control or inadequate economic resources limit access to information, to circumvent those restrictions and disseminate knowledge internationally. Individuals now have immediate access to information about the stock market, their bank accounts, current events, the weather, and consumer products.

Policy making

Social and economic innovations often occur spontaneously, as human beings respond in a natural way to new circumstances. Governments, legislators, urban planners and administrators are concerned with bringing about deliberate innovation through creating and implementing effective public policies to achieve certain goals. The cost of enforcing a new public policy must be weighed against the expected benefits. A policy change may have unforeseen, and sometimes unwanted, consequences.

Examples of public policies that have brought about positive social innovations are the granting of property rights to women, universal suffrage, welfare and unemployment compensation and mandatory education for children. Examples of public policy that resulted in harmful innovation are the Cultural Revolution initiated in 1966 by Mao Zedong, which closed universities and suppressed education for several years in China; the collectivization of agriculture in the U.S.S.R. by Joseph Stalin [4] which caused millions to die of starvation during 1931 and 1932; and the efforts of Pol Pot (Saloth Sar) in the 1970s to evacuate all urban dwellers to the countryside and return to an agricultural barter economy, which cost the lives of approximately 26 percent of Cambodia’s population. [5]

Organizations

In the context of an organization such as a corporation, local government, hospital, university, or non-profit organization, innovation is linked to performance and growth through improvements in efficiency, productivity, quality, and competitive positioning. A new management procedure, organizational structure, method of operation, communications device or product may be introduced in an effort to make the organization more efficient and productive. Successful innovation requires the definition of goals, knowledge of the materials and processes involved, financial and human resources, and effective management. A certain amount of experimentation is also necessary to adjust the new processes so that they produce the desired result.

Deliberate innovation involves risk. Organizations that do not innovate effectively may be destroyed by those that do. While innovation typically adds value, it may also have a negative or destructive effect as new developments clear away or change old organizational forms and practices. If the changes undermine employee morale, the new system may be less efficient than the old. Innovation can also be costly. The expense of purchasing and installing new equipment, computers and software, or of re-organizing, hiring and training staff is substantial, and may leave an organization without sufficient resources to continue its operations effectively. Organizations attempt to minimize risk by studying and analyzing innovations carried out by other organizations, by employing experts and consultants to carry out the innovation, and by following a number of formulas and management strategies.

The introduction of computers during the second half of the 20th century necessitated innovation in almost every type of organization. The productivity of individual workers was increased, and many clerical jobs were eliminated. Organizations made large investments in technology and created entire departments to maintain and manage computers and information, giving rise to a number of new professions. Paper documents were translated into electronic data. The workforce acquired new skills, and those who could not adapt dropped behind younger workers who were more familiar with technology and changed the dynamics of the workplace. Networks and internet connections allowed frequent and rapid communication within an organization. The centralization of information such as inventory, financial accounts and medical records made new types of analysis and measurement possible. While organizations benefited in many ways from the new technology, the expense and risk of innovating also increased.

Economics and business

The study and understanding of innovation is particularly important in the fields of business and economics because it is believed that innovation directly drives economic growth. The ability to innovate translates into new goods and services and entry into new markets, and results in increased sales. An increase in sales contributes to the prosperity of the workforce and increases its purchasing power, leading to a steady expansion of the economy.

In 1934, the European economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883 – 1955) defined economic innovation as:

- The introduction of a new good — that is one with which consumers are not yet familiar — or of a new quality of a good.

- The introduction of a new method of production, which need by no means be founded upon a discovery scientifically new, and can also exist in a new way of handling a commodity commercially.

- The opening of a new market, that is a market into which the particular branch of manufacture of the country in question has not previously entered, whether or not this market has existed before.

- The conquest of a new source of supply of raw materials or half-manufactured goods, again irrespective of whether this source already exists or whether it has first to be created.

- The carrying out of the new organization of any industry, like the creation of a monopoly position (for example through trustification) or the breaking up of a monopoly position:.[6]

Businesses recognize that innovation is essential for their survival, and seek to create a business model that fosters innovation while controlling costs[7]. Managers use mathematical formulas, behavioral studies and forecasting models to create strategies for implementing innovation. Business organizations spend between ½ of a percent (for organizations with a low rate of change) to more than 20 percent of their annual revenue on making changes to their established products, processes and services. The average investment across all types of organizations is four percent, spread across functions including marketing, product design, information systems, manufacturing systems and quality assurance.

Much of the innovation carried out by business organizations is not directed towards development of new products, but towards other goals such as reduction of materials and labor costs, improvement of quality, expansion of existing product lines, creation of new markets, reduction of energy consumption and lessening of environmental impact.

Many "breakthrough innovations" are the result of formal research and development, but innovations may be developed by less formal on-the-job modifications of practice, or through the exchange and combination of professional experience.

The traditionally recognized source of innovation is manufacturer innovation, where a person or business innovates in order to sell the innovation. Another important source of innovation is end-user innovation, in which a person or company develops an innovation for their own use because existing products do not meet their needs. [8] User innovators may become entrepreneurs selling their product, or more commonly, trade their innovation in exchange for other innovations or services. In the case of computer software, they may choose to freely share their innovations, using methods like open source. In such networks of innovation the creativity of the users or communities of users can further develop technologies and their use.

Analysts debate whether innovation is mainly supply-pushed (based on new technological possibilities) or demand-led (based on social needs and market requirements). They also continue to discuss what exactly drives innovation in organizations and economies. Recent studies have revealed that innovation does not just happen within the industrial supply-side, or as a result of the articulation of user demand, but through a complex set of processes that links input from not only developers and users, but a wide variety of intermediary organizations such as consultancies and standards associations. Examination of social networks suggests that much successful innovation occurs at the boundaries of organizations and industries where the problems and needs of users, and the potential of technologies are together in a creative process.

Diffusion of innovations

Once innovation occurs, innovations may be spread from the innovator to other individuals and groups. In 1962, Everett Rogers proposed that the life cycle of innovations can be described using the ‘s-curve’ or diffusion curve. The s-curve maps growth of revenue or productivity against time. In the early stage of a particular innovation, growth is relatively slow as the new product establishes itself. At some point consumer demand increases and product sales expand more rapidly. New incremental innovations or changes to the product allow growth to continue. Towards the end of its life cycle growth slows and may even begin to decline. In the later stages, no amount of new investment in that product will yield a normal rate of return.

Innovative companies will typically be constantly working on new innovations that will eventually replace older ones. Successive s-curves will come along to replace older ones and continue to drive growth upwards. In the figure above the first curve shows a current technology. The second shows an emerging technology that currently yields lower growth but will eventually overtake the current technology and lead to even greater levels of growth. The length of life will depend on many factors. [9]

The Bass diffusion model developed by Frank Bass in 1969 illustrates the process by which a new innovative product is adopted by new users, then is overtaken by products imitating the innovation. The model is widely used in forecasting, especially product forecasting and technology forecasting.

Schumpeter's focus on innovation is reflected in Neo-Schumpeterian economics, developed by such scholars as Christopher Freeman[10] and Giovanni Dosi[11] .

In the 1980s, Veneris (1984, 1990) developed a systems dynamics computer simulation model which takes into account business cycles and innovations.

Innovation is also studied by economists in a variety of contexts, for example in theories of entrepreneurship or in Paul Romer's New Growth Theory.

Failure of innovation

Success in implementing an innovation does not guarantee a beneficial outcome. Research shows that from fifty to ninety percent of innovation projects are judged to have made little or no contribution to the goals of the innovating organization. Innovations that fail are often potentially ‘good’ ideas but do not achieve desired results because of budgetary constraints, lack of skills, poor leadership, lack of knowledge, lack of motivation, or poor fit with current goals. The impact of failure goes beyond the simple loss of investment. Failure can also lead to loss of morale among employees, an increase in cynicism and even higher resistance to change in the future. Most companies allow for the possibility of failure when planning an innovation, and include processes for detecting problems before they consume too many resources and threaten the organization’s future.

Early detection of problems and adjustment of the innovation process contribute to the success of the final outcome. The lessons learned from failure often reside longer in the organizational consciousness than lessons learned from success.

Measures of innovation

Attempts to measure innovation take place on two levels: the organizational level and the political level. Within an organization, innovation can be evaluated by conducting surveys and workshops, consulting outside experts, or using internal benchmarks. There is no measure of organizational innovation. Corporate measurements generally utilize scorecards which cover several aspects of innovation such as financial data, innovation process efficiency, employees' contribution and motivation, and benefits for customers. The elements selected for these evaluations vary widely from company to company and may include new product revenue, amount spent on research and development, time to market, customer and employee perception and satisfaction, number of patents, and additional sales resulting from past innovations.

On a political level, measures of innovation are used to compare one country or region with another. The OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ) Oslo Manual of 1995 suggested standard guidelines for measuring technological product and process innovation. The new Oslo Manual of 2005 added marketing and organizational innovation. The Bogota Manual was created in 2001 for Latin America and the Caribbean countries. A traditional indicator used to measure innovation is expenditure, for example, investment in R&D (Research and Development) as a percentage of GNP (Gross National Product).

Economists Christopher Freeman (born 1921) and Bengt-Åke Lundvall developed the National Innovation System (NIS) to explain the flow of technology and information which is key to the innovative process on the national level. According to innovation system theory, innovation and technology development are results of a complex set of relationships among people, enterprises, universities and government research institutes.

The 2008-2009 Global Innovation Index created by Soumitra Dutta, a professor at French business school INSEAD, along with New Delhi based non-profit organization The Confederation of Indian Industry [12] ranks nations based on indices such as the number of internet users in a nation, the ease of doing business and the stability of banks. Every factor is then categorized as either an input or an output. Inputs indicate how conducive countries are to fostering innovation, and include institutions and policies, human capacity, infrastructure, technological sophistication, business markets and capital. The outputs indicate how effectively countries translate innovation into benefits such as knowledge, competitiveness and wealth. The top ten countries are listed below:

| Rank | Country | Region |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | North America | |

| 2 | Europe | |

| 3 | Europe | |

| 4 | Europe | |

| 5 | Asia | |

| 6 | Asia | |

| 7 | Europe | |

| 8 | Europe | |

| 9 | Asia | |

| 10 | Europe |

See also

- Creative destruction

- Creative problem solving

- Theories of technology

- Diffusion (anthropology)

- Ecoinnovation

- Emerging technologies

- Hype cycle

- Individual capital

- Information revolution

- Ingenuity

- Invention

- Innovation Economics

- Open Innovation

- Patent

- Public domain

- Research

- Timeline of invention

- User innovation

- Value network

Notes

- ↑ “innovation” Merriam Webster. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Max Mckeown, The Truth About Innovation. Pearson / Financial Times. 2008. ISBN 0273719122

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jan Fagerberg, "Innovation: A Guide to the Literature" in Fagerberg, Jan, David C. Mowery and Richard R. Nelson. The Oxford Handbook of Innovations. Oxford University Press. 2004. pp. 1–26. ISBN 0–19–926455–4.

- ↑ Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives. London: HarperCollins, 1991 (hardcover, ISBN 0002154943); New York: Vintage Books, 1993 (paperback, ISBN 0679729941). p. 269

- ↑ The Cambodian Genocide Program. Genocide Studies Program. Yale University (1994-2008). Retrieved Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ↑ Schumpeter, Joseph (1934). The Theory of Economic Development. Harvard University Press, Boston.

- ↑ Davila, Tony; Marc J. Epstein and Robert Shelton Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It. Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing. 2006. ISBN 0–13–149786–3 p. 6

- ↑ von Hippel, Eric (1988). The Sources of Innovation Retrieved February 10, 2009. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0–19–509422–0.

- ↑ Rogers, Everett M. (2003).Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.. New York, NY: Free Press.

- ↑ Freeman, Christopher (1982). The Economics of Industrial Innovation. Frances Pinter, London..

- ↑ Dosi, Giovanni (1982). Technological paradigms and technological trajectories. Research Policy 11 (3): 147–162.

- ↑ United States The World's Number One Innovator? Saabira Chaudhuri, Fast Company (January 7, 2009) Retrieved February 9, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barras, R. "Towards a theory of innovation in services". Research Policy 15: 161–73. 1984.

- Cabral, Regis. "Development, Science and". in Heilbron, J.. The Oxford Companion to The History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. 2003. pp. 205–207.

- Chakravorti, Bhaskar. The Slow Pace of Fast Change: Bringing Innovations to Market in a Connected World. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 2003.

- Byrd, Jacqueline. The Innovation Equation - Building Creativity & Risk Taking in your Organization. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer - Aprint. 2003. ISBN 0-7879-6250-3.

- Chesbrough, Henry William. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 2003. ISBN 1–57851–837–7.

- Christensen, Clayton M. . The Innovator's Dilemma. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 1997. ISBN 0–06–052199–6.

- Davila, Tony; Marc J. Epstein and Robert Shelton. Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It. Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing. 2006. ISBN 0–13–149786–3.

- Ettlie, John. Managing Innovation, Second Edition. Butterworth-Heineman, an imprint of Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 0–7506–7895-X.

- Fagerberg, Jan. "Innovation: A Guide to the Literature". in Fagerberg, Jan, David C. Mowery and Richard R. Nelson. The Oxford Handbook of Innovations. Oxford University Press. 2004. pp. 1–26. ISBN 0–19–926455–4.

- Freeman, Chris. The Economics of Industrial Innovation. Frances Pinter, London. 1982.

- Hesselbein, Frances, Marshall Goldsmith, and Iain Sommerville, ed (2002). Leading for Innovation: And organizing for results. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0–7879–5359–8.

- Hitcher, Waldo. Innovation Paradigm Replaced. Wiley. 2006.

- Luecke, Richard; Ralph Katz. Managing Creativity and Innovation. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 2003. ISBN 1–59139–112–1.

- Mckeown, Max. The Truth About Innovation. Pearson / Financial Times. 2008. ISBN 0273719122.

- Miles, Ian. "Innovation in Services". in Fagerberg, Jan, David C. Mowery and Richard R. Nelson. The Oxford Handbook of Innovations. Oxford University Press. 2004. pp. 433–458. ISBN 0–19–926455–4.

- OECD The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities. Proposed Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Technological Innovation Data. Oslo Manual. 2nd edition, DSTI, OECD / European Commission Eurostat, Paris 31 Dec 1995.

- Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of Innovation. New York, NY: Free Press. 1962.

- Rosenberg, Nathan Perspectives on Technology. Cambridge, London and N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. 1975.

- Schumpeter, Joseph. The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1934.

- Scotchmer, Suzanne. Innovation and Incentives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2004.

- Stein, Morris. Stimulating creativity. New York: Academic Press. 1974.

- von Hippel, Eric . Democratizing Innovation. 2005. MIT Press. ISBN 0–262–22074–1.

External links

All links retrieved February 11, 2009.

- Academic article on Being a Systems Innovator on SSRN

- "Communication on Innovation policy: updating the Union’s approach in the context of the Lisbon strategy" – The European Commission.

- Commission proposes 2009 to become European Year of Creativity and Innovation – The European Commission.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.