Skara Brae

| Heart of Neolithic Orkney* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | Scotland |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 514 |

| Region** | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1999 (23rd Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Skara Brae is a stone-built Neolithic settlement, located on the Bay of Skaill on the west coast of Mainland, the largest island in the Orkney archipelago of Scotland. It consists of several clustered houses, and was occupied from roughly 3180 B.C.E.–2200 B.C.E. Europe's most complete Neolithic village, Skara Brae gained UNESCO World Heritage Site status as one of four sites making up "The Heart of Neolithic Orkney." The site is one of four World Heritage Sites in Scotland, the others being the Old Town and New Town of Edinburgh; New Lanark in South Lanarkshire; and St Kilda in the Western Isles.

This ancient settlement, established 5,000 years ago (before Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids), is extremely well preserved, hidden under sand for four millennia. It provides an unparalleled opportunity to understand the lives of our remote ancestors. Its importance requires that it continue to be protected while still allowing researchers and tourists access to the site.

Discovery and Exploration

In the winter of 1850, a severe storm hit Scotland causing widespread damage. In the Bay of Skaill, the storm stripped the earth from a large irregular knoll, known as "Skerrabra." When the storm cleared, local villagers found the outline of a village, consisting of a number of small houses without roofs.[1]

William Watt of Skaill, the local laird, began an amateur excavation of the site, but after uncovering four houses the work was abandoned in 1868.[1] The site remained undisturbed for many years. In 1925 another storm swept away part of one of the houses and it was determined the site should be made secure. While constructing a sea-wall to protect the settlement, more ancient buildings were discovered.[1]

It was decided that more serious investigation was needed, and the job was given to University of Edinburgh Professor Vere Gordon Childe. Childe worked on the site from 1927 to 1930, publishing his findings in 1931.[2]

Childe originally believed that the settlement dated from around 500 B.C.E. and that it was inhabited by Picts.[2] However, radiocarbon dating of samples gathered during new excavations in 1972–1973 revealed that occupation of Skara Brae began about 3180 B.C.E.[3] This makes the site older that than Stonehenge and the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Description of the site

Four stone houses were revealed as a result of the storm in 1850, and later excavations revealed a total of six more structures, built into a large mound of domestic waste known as a midden. All the houses are built of closely fitting stone slabs forming one large rectangular room with rounded corners. Each house has a doorway which linked it to the other houses by means of low, covered passageways. The doorways were closed by stone slabs. This clustering, and the way the houses were sunk into the midden, provided good protection from the weather.[4] A sophisticated drainage system was even incorporated into the village's design, one that included a primitive form of toilet in each dwelling that drained into a communal sewer.

The houses had a fireplace as well as interior fittings comprising a stone dresser, two beds, shelves, and storage tanks. The covering of sand preserved the houses and their contents so well that Skara Brae is the best preserved Neolithic village in northern Europe, earning the nickname of the "Pompeii" of Scotland.[5]

Artifacts

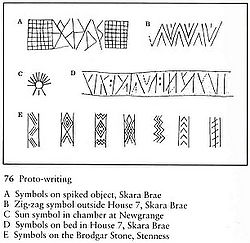

Artifacts discovered at the site include tools, pottery, jewelry, and carved stone objects. No weapons have been found. Among the carved stone objects are a number of enigmatic Carved Stone Balls, some of which are on display in the museum.[6] Similar objects have been found throughout northern Scotland. The spiral ornamentation on some of these "balls" has been stylistically linked to objects found in the Boyne Valley in Ireland.[7] Similar symbols were found carved into stone lintels and bed posts.[2]

Other artifacts made of animal, fish, bird, and whalebone, whale and walrus ivory, and killer whale teeth included awls, needles, knives, beads, adzes, shovels, small bowls and ivory pins up to 10 inches (25 cm) long.[8] These pins are very similar to examples found in passage graves in the Boyne Valley, another piece of evidence suggesting a linkage between the two cultures.[9] So-called Skaill knives, a type of knife found throughout Orkney and Shetland consisting of large flakes knocked off sandstone cobbles, were also found in Skara Brae.[10]

Nodules of haematite with highly polished surfaces were also found. The shiny surfaces suggest that the nodules were used to finish leather.[10] The 1972 excavations reached layers that had remained waterlogged and had preserved items that otherwise would have been destroyed. These include a twisted skein of heather, one of a very few known examples of Neolithic rope.[11]

Neolithic lifestyle

The houses used earth sheltering, sunk into the ground they were built into their middens. Although the midden provided the houses with a small degree of stability, its most important purpose was to act as a layer of insulation against Orkney's harsh winter climate. It is not clear what fuels the inhabitants used in the stone hearths. Gordon Childe was sure that the fuel was peat,[2] but a detailed analysis of vegetation patterns and trends suggests that climatic conditions conducive to the development of thick beds of peat did not develop in this part of Orkney until after Skara Brae was abandoned.[12] Other obvious possible fuel sources include driftwood and animal dung, and there is evidence that dried seaweed may have been a significant source.[13]

The dwellings contain a number of stone-built pieces of furniture, including cupboards, dressers, seats, and storage boxes. Each dwelling was entered through a low doorway that had a stone slab door that could be closed "by a bar that slid in bar-holes cut in the stone door jambs".[14] Seven of the houses have similar furniture, with the beds and dresser in the same places in each house. The dresser stands against the wall opposite the door, and would have been the first thing seen by anyone entering the dwelling. Each of these houses has the larger bed on the right side of the doorway and the smaller on the left. This pattern is in accord with Hebridean custom up to the early twentieth century where the husband's bed was the larger and the wife's was the smaller.[15] The discovery of beads and paint-pots in some of the smaller beds also supports this interpretation. At the front of each bed lie the stumps of stone pillars that may have supported a canopy of fur; another link with recent Hebridean style.[3]

The eighth house has no storage boxes or dresser, but has been divided into something resembling small cubicles. When this house was excavated, fragments of stone, bone, and antler were found. It is possible that this building was used as a house to make simple tools such as bone needles or flint axes.[16] The presence of heat-damaged volcanic rocks and what appears to be a flue, support this interpretation. House 8 is distinctive in other ways as well. It is a stand-alone structure not surrounded by midden,[8] instead there is a "porch" protecting the entrance through walls that are over 2 meters (6.6 ft) thick.

Skara Brae's inhabitants were apparently makers and users of grooved ware, a distinctive style of pottery that appeared in northern Scotland not long before the establishment of the village.[17] These people who built Skara Brae were primarily pastoralists who raised cattle and sheep.[2] Childe originally believed that the inhabitants did not practice agriculture, but excavations in 1972 unearthed seed grains from a midden suggesting that barley was cultivated.[15] Fish bones and shells are common in the middens indicating that dwellers supplemented their diet with seafood. Limpet shells are common and may have been fish-bait that was kept in stone boxes in the homes.[3] These boxes were formed from thin slabs with joints carefully sealed with clay to render them waterproof.

The lack of weapons, presence of Carved Stone Balls and other possible religious artifacts, as well as the quantity of jewelry led to speculation that Skara Brae might have been the home of a privileged theocratic class of wise men who engaged in astronomical and magical ceremonies at nearby sites like the Ring of Brodgar and the Standing Stones of Stenness.[18] The presence of a Neolithic "low road" connecting Skara Brae with the magnificent chambered tomb of Maeshowe, passing near both of these ceremonial sites,[4] supports this interpretation since low roads connect Neolithic ceremonial sites throughout Britain. However, there is no other archaeological evidence for such a claim, making it more likely that Skara Brae was inhabited by a pastoral community.[9]

Abandonment

Occupation of the Skara Brae houses continued for about six hundred years, ending in 2200 B.C.E.[4] There are many theories as to why the people of Skara Brae left, particularly popular interpretations involve a major storm. Evan Hadingham combined evidence from found objects with the storm scenario to imagine a dramatic end to the settlement:

As was the case at Pompeii, the inhabitants seem to have been taken by surprise and fled in haste, for many of their prized possessions, such as necklaces made from animal teeth and bone, or pins of walrus ivory, were left behind. The remains of choice meat joints were discovered in some of the beds, presumably forming part of the villagers' last supper. One woman was in such haste that her necklace broke as she squeezed through the narrow doorway of her home, scattering a stream of beads along the passageway outside as she fled the encroaching sand.[19]

Others disagree with catastrophic interpretations of the village's abandonment, suggesting a more gradual process:

A popular myth would have the village abandoned during a massive storm that threatened to bury it in sand instantly, but the truth is that its burial was gradual and that it had already been abandoned—for what reason, no one can tell.[10]

The site was farther from the sea than it is today, and it is possible that Skara Brae was built adjacent to a freshwater lagoon protected by dunes.[3] Although the visible buildings give an impression of an organic whole, it is certain that an unknown quantity of additional structures had already been lost to sea erosion before the site's rediscovery and subsequent protection by a seawall.[8] Uncovered remains are known to exist immediately adjacent to the ancient monument in areas presently covered by fields, and others, of uncertain date, can be seen eroding out of the cliff edge a little to the south of the enclosed area.

World Heritage status

"The Heart of Neolithic Orkney" was inscribed as a World Heritage site in December 1999, recognizing the importance of this 5,000 year-old settlement that is so well preserved. In addition to Skara Brae the site includes several other nearby sites.[20] It is managed by Historic Scotland.

In addition to Skara Brae the site includes:

- Maeshowe – a unique chambered cairn and passage grave, aligned so that its central chamber is illuminated on the winter solstice. It was looted by Vikings who left one of the largest collections of runic inscriptions in the world.[21]

- Standing Stones of Stenness – the four remaining megaliths of a henge, the largest of which is 6 metres (19 ft) high.[22]

- Ring of Brodgar – a stone circle 104 metres in diameter, originally composed of 60 stones set within a circular ditch up to 3 metres deep and 10 metres wide, forming a henge monument. Today only 27 stones remain standing. It is generally assumed to have been erected between 2500 B.C.E. and 2000 B.C.E. [23]

- Ness of Brodgar - between the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness, a site that has provided evidence of housing, decorated stone slabs, a massive stone wall with foundations, and a large building described as a Neolithic "cathedral".[24]

Due to the threat of coastal erosion from the ocean and damage by tourists, the site is monitored and steps have been taken to minimize damage, in an effort to preserve this significant site.[20] The Skara Brae site includes a visitor center and museum and a replica construction that allows visitors to fully understand the interior of these houses. The visitor center provides touch-screen presentations and artifacts discovered during archaeological excavations in the 1970s are on display.[25]

Related sites in Orkney

A comparable, though smaller, site exists at Rinyo on Rousay. The site was discovered in the winter of 1837-1938 on the lands of Bigland Farm in the north east of the island. It was excavated in 1938 and 1946 by Vere Gordon Childe and by W.G. Grant. Finds included flint implements, stone axes and balls, pottery and a stone mace-head.[26]

Knap of Howar on the Orkney island of Papa Westray, is a well preserved Neolithic farmstead. Dating from 3600 B.C.E. to 3100 B.C.E., it is similar in design to Skara Brae, but from an earlier period, and it is thought to be the oldest preserved standing building in northern Europe.[27]

There is also a site under excavation at Links of Noltland on Westray that appears to have similarities to Skara Brae. Findings at this site include a lozenge-shaped figurine believed to be the earliest representations of a human face ever found in Scotland.[28] Two further figurines were subsequently found at the site, one in 2010 and the other in 2012.[29] Other finds include polished bone beads, tools, and grooved ware pottery. The full extent of the site is believed to exceed the size of Skara Brae on the Orkney mainland.[30]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Skara Brae: The Discovery of the Village". Orkneyjar. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 V. Gordon Childe, Skara Brae, a Pictish Village in Orkney (Monograph of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, 1931).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 V. Gordon Childe and D.V. Clarke, Skara Brae (Edinburgh: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1983, ISBN 978-0114917555).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Rodney Castleden, The Stonehenge People (New York, NY: Routledge, 1987, ISBN 978-0710209689).

- ↑ Keith Savage, Scotland’s Pompeii: The Neolithic Village of Skara Brae. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Skara Brae BBC Scotland's History. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Stuart Piggott, Neolithic Cultures of the British Isles (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970, ISBN 978-0521077811).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 D.V. Clarke and Niall Sharples, "Settlements and Subsistence in the Third Millennium B.C.E.," in Colin Renfrew (ed.), The Prehistory of Orkney B.C.E. 4000-1000 C.E. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0852244562)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Graham Ritchie and Anna Ritchie, Scotland: Archaeology and Early History (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 1981, ISBN 978-0500273654).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Anna Ritchie, Prehistoric Orkney (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1995, ISBN 978-0713475937).

- ↑ Aubrey Burl, Prehistoric Avebury (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979, ISBN 978-0300023688), 144.

- ↑ T.H. Keatinge and J.H. Dickson, "Mid Flandrian Changes in Vegetation in Mainland Orkney." New Phytol 82(2) (1979): 585–612.

- ↑ Alexander Fenton, Northern Isles: Orkney and Shetland (John Donald Publishers Ltd, 1978, ISBN 978-0859760195), 206–209.

- ↑ V. Gordon Childe and W. Douglas Simpson, Illustrated History of Ancient Monuments: Vol. VI Scotland (Edinburgh: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1952).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Lloyd Laing, Orkney and Shetland: An Archaeological Guide (Newton Abbott: David & Charles, 1974, ISBN 978-0715363058).

- ↑ Roger B. Beck, Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor, and Dahia Ibo Shabaka, World History: Patterns of Interaction (Evanston, IL: McDougal Littel, 2005, ISBN 978-0618187744).

- ↑ Timothy Darvill, Prehistoric Britain (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0300039511), 85.

- ↑ Euan MacKie, Science and Society in Prehistoric Britain (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1977, ISBN 978-0312702458).

- ↑ Evan Hadingham, Circles and Standing Stones: An Illustrated Exploration of the Megalith Mysteries of Early Britain (New York, NY: Walker and Company, 1975, ISBN 978-0802704634), 66.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Jane Downes, Description and status of The Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Maeshowe". Orkneyjar. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ "The Standing Stones o' Stenness". Orkneyjar. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ The Ring o' Brodgar, Stenness Orkneyjar. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ John Ross and David Hartley, " 'Cathedral' as old as Stonehenge unearthed." Edinburgh. The Scotsman, August 13, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Skara Brae Prehistoric Village Historic Scotland. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Rousay, Rinyo" RCAHMS. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ The Knap o' Howar, Papay Orkneyjar. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Face to face with the 5,000-year-old 'first Scot' The Scotsman August 20, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Third 5,000-year-old figurine found at Orkney dig BBC News, August 28, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Caroline Lewis, Archaeologists Find Mysterious Neolithic Structure In Orkney Links Of Noltland Dig Culture24, December 19, 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beck, Roger B., Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor, and Dahia Ibo Shabaka. World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littel, 2005. ISBN 978-0618187744

- Burl, Aubrey. The Stone Circles of the British Isles. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0300019728

- Burl, Aubrey. Prehistoric Avebury. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0300023688

- Castleden, Rodney. The Stonehenge People. New York, NY: Routledge, 1987. ISBN 978-0710209689

- Childe, V. Gordon. Skara Brae, a Pictish Village in Orkney. Monograph of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, 1931. ASIN B002A6UOWQ

- Childe, V. Gordon, and W. Douglas Simpson. Illustrated History of Ancient Monuments: Vol. VI Scotland. Edinburgh: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1952.

- Childe, V. Gordon, and D.V. Clarke. Skara Brae. Edinburgh: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1983. ISBN 978-0114917555

- Clarke, D. V., Patrick Maguire, and C.J. Tabraham. Skara Brae : Northern Europe's Best Preserved Neolithic Village. Historic Scotland, 2000. ISBN 978-1900168977

- Darvill, Timothy. Prehistoric Britain. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0300039511

- Fenton, Alexander. Northern Isles: Orkney and Shetland. John Donald Publishers Ltd, 1978. ISBN 978-0859760195

- Hadingham, Evan. Circles and Standing Stones: An Illustrated Exploration of the Megalith Mysteries of Early Britain. New York, NY: Walker and Company, 1975. ISBN 978-0802704634

- Hedges, John W. Tomb of the Eagles: Death and Life in a Stone Age Tribe. New York, NY: New Amsterdam, 1984. ISBN 978-0941533058

- Keatinge, T.H., and J.H. Dickson. "Mid Flandrian Changes in Vegetation in Mainland Orkney." New Phytol 82(2) (1979): 585–612.

- Laing, Lloyd. Orkney and Shetland: An Archaeological Guide. Newton Abbott: David & Charles, 1974. ISBN 978-0715363058

- Laing, Lloyd, and Jennifer Laing. The Origins of Britain. London: Paladin, 1982. ISBN 978-0586083703

- MacKie, Euan. Science and Society in Prehistoric Britain. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1977. ISBN 978-0312702458

- Piggott, Stuart. Neolithic Cultures of the British Isles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970. ISBN 978-0521077811

- Renfrew, Colin (ed.). The Prehistory of Orkney B.C.E. 4000-1000 C.E. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0852244562

- Ritchie, Graham, and Anna Ritchie. Scotland: Archaeology and Early History. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 1981. ISBN 978-0500273654

- Ritchie, Anna. Prehistoric Orkney. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1995. ISBN 978-0713475937

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- Scotland’s Pompeii: The Neolithic Village of Skara Brae by Keith Savage.

- Historic Scotland: Skara Brae Prehistoric Village.

- Skara Brae: The discovery of the village Orkneyjar.

- Skara Brae Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

- Skara Brae BBC Scotland's History.

| World Heritage Sites in the United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

Blenheim Palace · Canterbury Cathedral – St. Augustine's Abbey – St. Martin's Church · Bath · Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape · Derwent Valley Mills · Durham Castle and Cathedral · Ironbridge Gorge · Jurassic Coast · Frontiers of the Roman Empire (Hadrian's Wall) · Kew Gardens · Liverpool · Maritime Greenwich · Westminster Palace – Westminster Abbey – St. Margaret's Church · Saltaire · Stonehenge and Avebury · Studley Royal Park and Fountains Abbey · Tower of London | |

Edinburgh Old Town and New Town · Heart of Neolithic Orkney (Maeshowe • Ring of Brodgar • Skara Brae • Standing Stones of Stenness) · New Lanark · St. Kilda | |

Castles and Town Walls of King Edward I in Gwynedd (Beaumaris Castle • Caernarfon Castle • Conwy Castle • Harlech Castle) · Blaenavon | |

| Giant's Causeway | |

| Overseas territories | Henderson Island · Gough Island and Inaccessible Island · St. George's Town |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.