Saqqarah

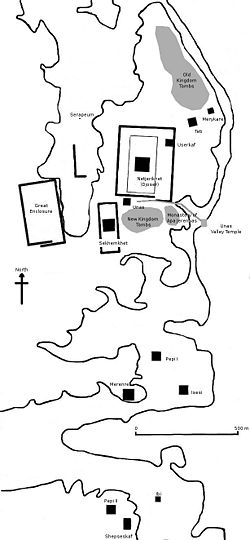

Saqqarah, Saqqara or Sakkara (Arabic: سقارة) is a vast, ancient burial ground in Egypt, featuring the world's oldest standing step pyramid (). It is located some 30 km south of modern-day Cairo and covers an area of around 7 km by 1.5 km. While Memphis was the capital of Ancient Egypt, Saqqara served as its necropolis. Although it was eclipsed as the burial ground of royalty by the Pyramids of Giza and later by the Valley of the Kings in Thebes, it remained an important complex for minor burials and cult ceremonies for more than 3,000 years, well into Ptolemaic and Roman times.

The step pyramid at Saqqara, designed by Imhotep for King Djoser (c. 2667-2648 B.C.E.), is the oldest complete hewn-stone building complex known in history. It is now the location of the Imhotep Museum which allows visitors to better appreciate the incredible work of this early architect as well gain a better understanding of the civilization of Ancient Egypt, so significant in the course of human history. Saqqara is designated, together with the Pyramids of Giza, as a World Heritage Site.

Early dynastic

Although the earliest burials of nobles at Saqqara can be traced back to the First Dynasty, it was not until the Second Dynasty that the first kings were buried there, including Hotepsekhemwy and Nynetjer.

Old Kingdom

The most striking feature of the necropolis dates from the Third Dynasty. Still visible today is the Step Pyramid of the Pharaoh Djoser. In addition to Djoser's, there are another 16 pyramids on the site, in various states of preservation or dilapidation. That of the fifth-dynasty Pharaoh Unas, located just to the south of the step pyramid and on top of Hotepsekhemwi's tomb, houses the earliest known example of the Pyramid Texts—inscriptions with instructions for the afterlife used to decorate the interior of tombs, the precursor of the New Kingdom Book of the Dead. Saqqara is also home to an impressive number of mastaba tombs.

Because the necropolis was lost beneath the sands for much of the past two millennia—even the sizable mortuary complex surrounding Djoser's pyramid was not uncovered until 1924—many of these have been superbly preserved, with both their structures and lavish internal decorations intact.

Major Old Kingdom structures

Pyramid of Djoser

The Pyramid of Djoser, or kbhw-ntrw ("libation of the deities") was built for the Pharaoh Djoser by his architect, Imhotep. It was constructed during twenty-seventh century B.C.E.

This first Egyptian pyramid consisted of mastabas (of decreasing size) built atop one another in what were clearly revisions of the original plan. The pyramid originally stood 62 meters tall and was clad in polished white marble. The step pyramid (or proto-pyramid) is considered to be the earliest large-scale stone construction.

Sekhemkhet's step pyramid (the Buried Pyramid)

While there was known be a successor to Djoser, Sekhemkhet's name was unknown until 1951, when the leveled foundation and vestiges of an unfinished Step Pyramid were discovered by Zakaria Goneim. Only the lowest step of the pyramid had been constructed at the time of his death. Jar seals found on the site were inscribed with this king's name. From its design and an inscription from his pyramid, it is thought that Djoser's famous architect Imhotep had a hand in the design of this pyramid. Archaeologists believe that Sekhemket's pyramid would have been larger than Djoser's had it been completed. Today, the site, which lies southwest of Djoser's complex, is mostly concealed beneath sand dunes and is known as the Buried Pyramid.

Gisr el-mudir

Gisr el-mudir, located just west of Sekhemkhet's pyramid complex, is a massive enclosure that seems to date from the Second dynasty. The structure was located in the early twentieth century, but not investigated until the mid-1990s, when it was found to be masonry of roughly hewn limestone blocks in layers, making it the earliest known stone structure in Egypt.

Shepseskaf's Mastabat Fara'un

Located in south Saqqara, the structure known as Mastabat Fara'un is the burial place of king Shepseskaf, of the Fourth Dynasty.

Userkaf's Pyramid

The Pyramid complex of Userkaf is located in the pyramid field. Constructed in dressed stone, with a core of rubble, the pyramid now resembles a conical hill just to the north of the Step Pyramid of Djoser Netjerikhet.

The interior was first explored by John Shae Perring in 1839, though a robber's tunnel previously discovered by Orazio Marucchi in 1831. Perring thought the pyramid belonged to Djedkare. The pyramid was first correctly identified by Egyptologist Cecil Firth in 1928. The pyramid introduced several new changes from the previous dynasty. In comparison with the tombs of the Fourth dynasty, his pyramid was rather small, measuring under 50 meters high with sides only 73 and 30 meters long. Still, small or not, unlike his predecessor on the throne, Shepseskaf, who chose to be buried in a simple mastaba, Userkaf was buried in a pyramid. Userkaf's increased focus, however, was put less on the pyramid itself than on the mortuary temple, which were more richly decorated than in the previous Fourth dynasty. In the temple courtyard, a colossal statue of the king was raised.

Djedkare Isesi pyramid complex, known as Haram el-Shawaf

Haram el-Shawaf (Arabic: حرم الشواف) (The Sentinel), located in south Saqqara, is a pyramid complex built by Djedkare Isesi and was originally called Beautiful is Djedkare-Isesi. The complex includes the main pyramid, a satellite pyramid, and an associated pyramid which is probably that of his unnamed consort, and is hence known as The Pyramid of the Unknown Queen.[1]

Pyramid of Unas

The Pyramid Complex of Unas is located in the pyramid field at Saqqara. The pyramid of Unas of the Fifth Dynasty (originally known as "Beautiful are the Places of Unas") is now ruined, and looks more like a small hill than a royal pyramid.

It was investigated by Perring and then Lepsius, but it was Gaston Maspero who first gained entry to the chambers in 1881, where he found texts covering the walls of the burial chambers. These, together with others found in nearby pyramids are now known as the Pyramid Texts. In the burial chamber itself the remains of a mummy were found, including the skull, right arm, and shin, but whether these belong to Unas is not certain.

Near to the main pyramid, to the north east, there are mastabas that contain the burials of the consorts of the king.

Teti's pyramid complex

Teti was the first Pharaoh of the Sixth dynasty of Egypt. During Teti's reign high officials were beginning to build funerary monuments that rivaled that of the Pharaoh. For example, his chancellor built a large mastaba consisting of 32 rooms, all richly carved. This is considered a sign that wealth was being transferred from the central court to the officials, a slow process that culminate in the end to the Old Kingdom. His pyramid complex is associated with the mastabas of officials from his reign.

The Pyramid complex of Teti is located in the pyramid field. The preservation above ground is very poor, and it now resembles a small hill. Below ground the chambers and corridors are very well preserved.

Pepi II pyramid complex

Pepi II's pyramid complex (originally known as Pepi's Life is Enduring) is located close to many other Old Kingdom pharaohs. His pyramid is a modest affair compared to the great pyramid builders of the Fourth Dynasty, but was comparable to earlier pharaohs from his own dynasty. It was originally 78.5 meters high, but erosion and relatively poor construction has reduced it 52 meters.

The pyramid was the center of a sizable funerary complex, complete with a separate mortuary complex, a small, eastern satellite pyramid. This was flanked by two of his wives' pyramids to the north and north-west (Neith (A) and Iput II respectively), and one to the south-east (Udjebten), each with their own mortuary complexes. Perhaps reflecting the decline at the end of his rule, the fourth wife, Ankhenespepy IV, was not given her own pyramid but was instead buried in a store room of the Iput's mortuary chapel. Similarly, Prince Ptahshepses, who likely died near the end of Pepi II's reign, was buried in the funerary complex of a previous pharaoh, Unas, within a "recycled" sarcophagus dating to the Fourth Dynasty.

The ceiling of the burial chamber is decorated with stars, and the walls are lined with passages from the Pyramid texts. An empty black sarcophagus bearing the names and titles of Pepi II was discovered inside.

Following in the tradition of the final pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty, Unas and of his more immediate predecessors Teti, Pepi I and Merenre, the interior of Pepi II's pyramid is decorated with what has become known as the Pyramid Texts, magical spells designed to protect the dead. Well over 800 individual texts (known as "utterances") are known to exist, and Pepi II's contains 675 such utterances, the most in any one place.

It is thought that this pyramid complex was completed no later than the thirtieth year of Pepi II's reign. No notable funerary constructions of note happened again for at least 30, and possibly as long as 60 years, due indirectly to the king's incredibly long reign. This meant there was a significant generational break for the trained stonecutters, masons, and engineers who had no major state project to work on and to pass along their practical skills. This may help explain why no major pyramid projects were undertaken by the subsequent regional kings of Herakleopolis during the First Intermediate Period.

Gustav Jéquier investigated the complex in detail between 1926 and 1936.[2] Jéquier was the first excavator to start actually finding any remains from the tomb reliefs, and he was the first to publish a thorough excavation report on the complex.[3]

Ibi

Quakare Ibi was buried in a small pyramid at Saqqara-South. It was the last pyramid built in Saqqara, and was built to the northeast of Shepseskaf's tomb and near the causeway of the pyramid of Pepi II.[4] It is now almost totally destroyed.

New Kingdom Necropolis

While most of the mastabas date from the Old Kingdom, there are a few pyramids that date from the First Intermediate Period, the most notable being Khendjer's Pyramid in South Saqqara.

One major figure from the New Kingdom is also represented: Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the eighteenth Dynasty, who had a tomb built for himself before he assumed the throne in his own right, while still serving as one of Tutankhamun's generals. However, it should be noted that Pharaoh Horemheb was never buried here. After his death he was interred, as were many other 18th Dynasty kings, in the Valley of the Kings in Ancient Thebes.

Later burials and monuments

Another major monument at Saqqara is the Serapeum: A gallery of tombs, cut from the rock, which served as the eternal resting place of the mummified bodies of the Apis bulls worshiped in Memphis as embodiments of the god Ptah. Rediscovered by Auguste Mariette in 1851, the tombs had been opened and plundered in antiquity—with the exception of one that lay undisturbed for some 3,700 years. The mummified bull it contained can now be seen in Cairo's agricultural museum.

On the approach to the Serapeum stands the slightly incongruous arrangement of statues known the Philosophers' Circle: A Ptolemaic recognition of the greatest poets and thinkers of their Greek ancestors, originally situated in a nearby temple. Represented here are Hesiod, Homer, Pindar, Plato, and others.

Imhotep museum

The Imhotep Museum is located at the foot of the Saqqara necropolis complex and was built as part of strategic site management.[5]

The Museum was opened on April 26, 2006, and displays finds from the site, in commemoration of the ancient Egyptian architect Imhotep. Zahi Hawass said: "I felt that we should call it the Imhotep Museum in tribute to the first architect to use stone rather than perishable materials for the construction on a large scale. This man was second only to the King and in the late period was worshiped as a god."

A monument hall is also dedicated to an important Egyptologist, who excavated the Djoser complex for the all his life: Jean-Philippe Lauer. The Museum has five large halls in which the people can admire masterpieces from Saqqara, such as the Greco-Roman mummy discovered by Zahi Hawass during the excavation at Teti's pyramid complex. Also on display is the magnificent pair of Nineteenth Dynasty statues depicting the high priest of Mut Amenemhotep and his wife, found in the vicinity of the causeway of Unas complex.

In the entrance hall, the visitor is welcomed by a fragment of the Djoser statue which reads name of the king, and consequently for the first time in the history the name of the architect Imhotep. The second hall allows recent finds to be viewed and enjoyed, and they will are rotated in the display. The third hall is dedicated to Imhotep's architecture, and it exhibits examples of elements from the Step Pyramid Complex. The fourth hall is called "Saqqara Style" and shows vessels and statues in friezes and structures of wood and stones. The fifth hall is called the "Saqqara Tomb," wherein objects used in burial from the sixth Dynasty through the New Kingdom are on display.

Notes

- ↑ Egypt Photo, The Pyramid Complex of Djedkare-Isesi. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (The British Museum Press, 1995).

- ↑ Gustav Jéqier, Le monument funéraire de Pepi II (Cairo, 1941).

- ↑ The Ancient Egypt, "Saqqara, City of the Dead: The Pyramid of Ibi." Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ www.ahram.or, Museum for a demi-god Retrieved September 24, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Davies, Sue and H.S. Smith. 2006. The Sacred Animal Necropolis at North Saqqara: The Main Temple Complex: The Archaeological Report. Egypt Exploration Society. ISBN 0856981702

- Jéquier, Gustave. 1936. Le monument funéraire de Pepi II. Fouilles à Saqqarah. Le Caire: Imperimerie de l'institute Français d'archéologie Orientale.

- Shaw, Ian and Paul Nicholson. 2003. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0810990962

- Ziegler, C. 2007. Le Mastaba d'Akhethetep (Fouilles Du Louvre A Saqqara). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9042919221

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Gisr el-Mudir.

- New finds at Egypt's city of dead.

- Friends of Saqqara.

- The Pyramid Complex of Djedkare-Isesi.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.