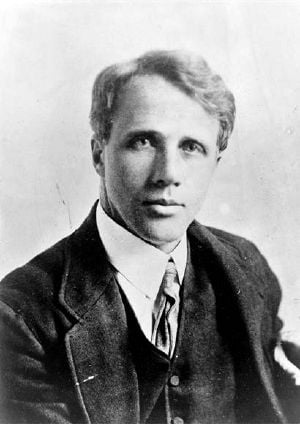

Robert Frost

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 - January 29, 1963) was an American poet, arguably the most recognized American poet of the twentieth century. Frost came of age during a time when modernism was the dominant movement in American and European literature. Yet, distinct from his contemporaries, Frost was a staunchly un-modern poet. He relied on the same poetic tropes that had been in use in English since poetry's inception: Rhyme, meter, and formalized stanzas, wryly dismissing free verse by claiming, "I'd just as soon play tennis with the net down."

Modernist poetry largely abandoned conventional poetic forms as obsolete. Frost powerfully demonstrated that they were not by composing verse that combined a clearly modern sensibility with traditional poetic structures. Accordingly, Frost has had as much or even more influence on present-day poetryâwhich has seen a resurgence in formalismâthan many poets in his own time.

Frost endured much personal hardship, and his verse drama, "A Masque of Mercy" (1947), based on the story of Jonah, presents a deeply felt, largely orthodox, religious perspective, suggesting that man with his limited outlook must always bear with events and act mercifully, for action that complies with God's will can entail salvation. "Nothing can make injustice just but mercy," he wrote.

Frost's enduring legacy goes beyond his strictly literary contribution. He gave voice to American, and particularly New England virtues.

Life

Although widely associated with New England, Robert Frost was born in San Francisco to Isabelle Moodie, of Scottish birth, and William Prescott Frost, Jr., a descendant of a Devonshire Frost, who had sailed to New Hampshire in 1634. His father was a former teacher turned newspaper man, a hard drinker, a gambler, and a harsh disciplinarian, who fought to succeed in politics for as long as his health allowed.

Frost lived in California until he was 11. After the death of his father, he moved with his mother and sister to eastern Massachusetts near his paternal grandparents.An indifferent student in his youth, he took seriously to his studies and graduated from Lawrence High School as valedictorian and class poet in 1892. He also absorbed New England's distinctive speech patterns, taciturn character types, and regional customs. He attended Dartmouth College where he was a member of the Theta Delta Chi fraternity, and from 1897 to 1899, and Harvard University where he studied philology without completing his degree. Eventually, after purchasing a farm in Derry, New Hampshire, he became known for his wry voice that was both rural and personal.

Frost was married to Elinor Miriam White and they had six children. In March 1894, The Independent in Lawrence, Massachusetts published Frost's poem, "My Butterfly: An Elegy," his first published work, which earned him $15. At this time, Frost made an important decision, deciding to devote his time to poetry instead of teaching. The Frosts made another important decision at this time: Robert wanted to move to Vancouver, his wife to England; the toss of a coin selected England.

So in 1912, Frost sold his farm and moved to England, to the Gloucestershire village of Dymock, to become a full-time poet. His first book of poetry, A Boy's Will, was published the next year. In England, he made some crucial contacts including Edward Thomas (a member of the group known as the Dymock poets), T.E. Hulme, and Ezra Pound, who was the first American to write a (favorable) review of Frost's work. Frost returned to America in 1915, bought a farm in Franconia, New Hampshire, and launched a career of writing, teaching, and lecturing. From 1916 to 1938, he was an English professor at Amherst College, where he encouraged his writing students to bring the sound of the human voice to their craft.

He recited his work, "The Gift Outright," at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy in 1961 and represented the United States on several official missions. He also became known for poems that include an interplay of voices, such as "Death of the Hired Man." Other highly acclaimed poems include "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening," "Mending Wall," "Nothing Gold Can Stay," "Birches," "After Apple Picking," "The Pasture," "Fire and Ice," "The Road Not Taken," and "Directive." His pastoral descriptions of apple trees and stone walls, and flinty poetic persona, typified the modern image of rural New England.

Personal trials

Frost's personal life was plagued with grief and loss. His father died of tuberculosis in 1885, when Frost was 11, leaving the family with just $8. Frost's mother died of cancer in 1900. In 1920, Frost had to commit his younger sister, Jeanie, to a mental hospital, where she died nine years later. Mental illness apparently ran in Frost's family, as both he and his mother suffered from depression, and his daughter Irma was committed to a mental hospital in 1947. Frost's wife, Elinor, also experienced bouts of depression.

Elinor and Robert Frost had six children: son Elliot (1896-1904, died of cholera), daughter Lesley Frost Ballantine (1899-1983), son Carol (1902-1940, committed suicide), daughter Irma (1903-?), daughter Marjorie (1905-1934, died as a result of puerperal fever after childbirth), and daughter Elinor Bettina (died three days after birth in 1907). Only Lesley and Irma outlived their father. Frost's wife, who had heart problems throughout her life, developed breast cancer in 1937, and died of heart failure in 1938.

Many critics recognize a dark and pessimistic tone in some of Frost's poetry, with notes of despair, isolation, and endurance of hardship suggesting the personal turmoil of the poet.

During his later years he spent summers in Ripton, Vermont and participated in the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference at Middlebury College. On his death on January 29, 1963, Robert Frost was buried in the Old Bennington Cemetery, in Bennington, Vermont.

Poetry

Frost has always been a difficult figure to categorize in American poetry. His life spans the extent of the Modern Period. His contemporaries included Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and William Carlos Williams, yet he shares none of their radicalism. From his first book of poems to the end of his career, Frost wrote in strict rhyme and measure.

His adherence to form during a time when most poets were turning to free verse or experimentalism made him one of the most accessible poets of his generation, and likely counts a great deal for his enduring popularity. It is easy to mistake Frost's formalism for simplicity or anachronism. Dedicated readers know, however, that beneath his traditional-sounding verses there is a distinctly modern thinker writing with tremendous acuity.

A common perception of Frost has been that of an old man on a porch, whittling some woodwork, and perhaps smoking a corncob pipe, who leans over from his rocking chair as people pass by and chides them to take the road less traveled. He has often been short-changed as being simply, "a wise old man who writes in rhymes." But Frost, in private life, was a man in striking contrast to the image of wise old farmer that had made him so popular, and he was not at all content to simply echo hollow commonsense. As he writes in his aphoristic essay, "The Figure a Poem Makes,"

- A school boy may be defined as one who can tell you what he knows in the order in which he learned it.

- The artist must value himself as he snatches a thing from some previous order in time and space

- into a new order with not so much as a ligature clinging to it of the old place where it was organic.

Much of the wisdom that Frost gathered organicallyâ"sticking to his boots like burrs" as one of his favorite turns of phrase puts itâmay have been gathered from rustic life and may seem good old-fashioned commonsense. But Frost was an exacting artist, and he took nothing that he learned at face value; never would he stoop to being a school-boy poet (similar to the sedate, pedagogical poets of the Victorian era, whom he despised) writing poems that simply expounded truisms without any ring of truth.

In his prose particularly, Frost's intense ruminations about the means of making a poem becomes apparent. His greatest contribution to poesy lies in his invention of what he called the "sentence-sound," and its relation to theories of poetic tone laid out, in among other places, Ezra Pound's ABC of Reading. The sentence-sound, for Frost, was the tonal sound of a sentence separate from the sound or meaning of its words. He compared it to listening to a conversation heard behind a closed door: The words are muffled, but a vague sense of meaning, carried in the tone of the sentences themselves, can still be heard. Alternatively, he suggested that sentence-sounds can be recognized in sentences that one knows instinctively how to read aloud. For instance:

- "Once upon a time, and a very good time it wasâ¦" or,

- "Those old fools never knew what hit them," or,

- "And that has made all the difference."

This technique is apparent in Frost's best poems, where colloquial expressions that ring with commonplace tones emerge out of the gridwork of the rigid meter. Most of the other poets of the modern period (and most poets of the twentieth century on, for that matter) have cast off meter, thinking that it will inevitably force the poet to write with a stiff, antiquated tone. Yet Frost, at his best, proves his motto that "Poetry is the renewal of words forever and ever," by renewing traditional poetic forms with the fresh sentence-sounds of American speech. Consider for instance these lines from his famous poem "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening:"

- The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

- But I have promises to keep,

- And miles to go before I sleep,

- And miles to go before I sleep.

The repetition of the last line reinforces the exhausted, sing-song tone of the final sentence. The poem itself sounds surprisingly speech-like despite its strict meter and obvious rhyme. Consider a similar effect in the final quatrain of his eerie lyric poem, "The Most of It," where the last line in its complete ordinariness hits the reader like a whoosh of cold air:

- â¦Pushing the crumpled water up ahead,

- And landed pouring like a waterfall,

- And stumbled through the rocks with horny tread

- And forced the underbrush, and that was all.

Frost at his best is able to write poems that, although transparently poetic and rhymed, sound strikingly conversational to the ear. Another example of his constant experimentation with the place of American speech in formal poetry (a concern remarkably similar to that of his contemporary William Carlos Williams), are Frost's numerous dialogue poems, which tend to take on the form of abstruse philosophical arguments carried across several voices, in sharp departure from his more familiar nature poems. The effect of his poetry in total is decidedly modern, and Frost's greatest poems are indebted as much to the twentieth century New England he lived and wrote in as to the generations of metrical poets he venerated in his obeisance to forms.

Legacy

Robert Frost held an anomalous place in twentieth century literature, joining aspects of the modernist temperament with standard poetic forms. His work reflects pastoral aspects of Thomas Hardy and William Wordsworth, the introspection and familiar imagery of Emily Dickinson, and typically New England characteristics of self-reliance and sense of place found in the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, James Russell Lowell, and John Greenleaf Whittier. But Frost's irony and ambiguity, his skepticism and honesty reflect a distinctly modern awareness.

Frost was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for poetry four times: In 1924, 1931, 1937 and 1943. Frost was also the Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1958-59, a position renamed as Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry, or simply Poet Laureate, in 1986.

Frost received honorary degrees from Harvard University, Bates College, Oxford, and Cambridge universities; and he was the first person to receive two honorary degrees from Dartmouth College. During his life, the Robert Frost Middle School in Fairfax, Virginia and the main library of Amherst College were named after him. In 1971, the Robert Frost Middle School in Rockville, Maryland was also named after him.

External links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

- Robert Frost on Poets.orgâBiography, poems, and related essays, from the Academy of American Poets

- Frost at Modern American Poetry

- Brief biography & poems

- Works by Robert Frost. Project Gutenberg

- Several of Frost's early books online

- A collection of poetry by Robert Frost

- Review of Robert Frostâs Birches

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.