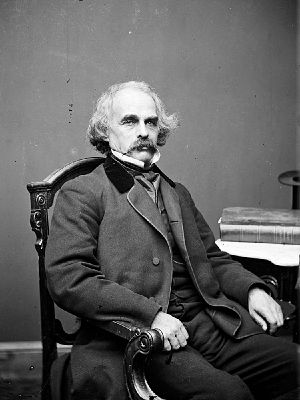

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 ‚Äď May 19, 1864) was a nineteenth-century American novelist and short story writer. He is recognized, with his close contemporaries Herman Melville and Walt Whitman, as a key figure in the development of a distinctly American literature.

Like Melville, Hawthorne was preoccupied with New England's religious past. For Melville religious doubt was an unspoken subtext to much of his fiction, while Hawthorne brooded over the Puritan experience in his novels and short stories. The direct descendant of John Hathorne, a presiding judge at the Salem witch trials in 1692, Hawthorne struggled to come to terms with Puritanism within his own sensibility and as the nation expanded geographically and intellectually.

In Hawthorne's greatest novel, The Scarlet Letter, set in a seventeenth-century Puritan town, Hester Pryme is forced to wear a scarlet letter A because of an adulterous relationship with a man whose identity she steadfastly protects. While not condoning the adultery, the novel presents Hester and her child, Pearl, as purified through the ordeal of public condemnation, while the Puritan townspeople and clergy are revealed as hypocrites and Hester's moral inferiors.

Contrary to the meticulous social realism that dominated European prose in the nineteenth century, Hawthorne's tales explore problems of sin, guilt, and hypocrisy through allegory and emphasis on the supernatural. Hawthorne was also a friend and neighbor of leading New England Transcendentalists and shared their reverence for nature and impatience with religious orthodoxy. Hawthorne's works offer a probing investigation into the psychology of nineteenth-century America as it moved beyond its Puritan past toward a more inclusive national identity.

Biography

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born in Salem, Massachusetts, where his birthplace is now a house museum. Hawthorne's father was a sea captain and descendant of John Hathorne, one of the judges who oversaw the Salem Witch Trials. (The author added the "w" to his surname in his early twenties.) Hawthorne's father died at sea in 1808 of yellow fever when Hawthorne was only four years old, so Nathaniel was raised secluded from the world by his mother.

Hawthorne attended Bowdoin College in Maine from 1821 to 1824, becoming friends with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and future president Franklin Pierce. Until the publication of his Twice-Told Tales in 1837, Hawthorne wrote in the comparative obscurity of what he called his "owl's nest," a garret in the family home. Looking back on this period of his life, on June 4, 1837, he wrote : "I have not lived, but only dreamed about living."[1] And yet it was this period of brooding and writing that had formed, as Malcolm Cowley was to describe it, "the central fact in Hawthorne's career," his "term of apprenticeship" that would eventually result in his "richly meditated fiction."[2]

Hawthorne was hired in 1839 as a weigher and gauger at the Boston Custom House. He had become engaged in the previous year to the illustrator and transcendentalist Sophia Peabody. Seeking a possible home for himself and Sophia, he joined the transcendentalist utopian community at Brook Farm in 1841; later that year, however, he left when he became dissatisfied with the experiment. (His Brook Farm adventure would prove an inspiration for his novel, The Blithedale Romance.) He married Sophia in 1842; they moved to The Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, where they lived for three years. Hawthorne and his wife then moved to The Wayside, previously a home of the Alcotts. Their neighbors in Concord included Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

Like Hawthorne, Sophia was a reclusive person. She was, in fact, bedridden with headaches until her sister introduced her to Hawthorne, after which her headaches seem to have abated. The Hawthornes enjoyed a long marriage, and Sophia was greatly enamored of her husband's work. In one of her journals, she writes: "I am always so dazzled and bewildered with the richness, the depth, the… jewels of beauty in his productions that I am always looking forward to a second reading where I can ponder and muse and fully take in the miraculous wealth of thoughts."[3]

In 1846 Hawthorne was appointed surveyor (determining the quantity and value of imported goods) at the Salem Custom House. Like his earlier appointment to the custom house in Boston, this employment was vulnerable to the politics of the time. When Hawthorne later wrote The Scarlet Letter, he included a long introductory essay depicting his time at the Salem Custom House. Due to the common practice of the spoils system, he lost this job due to the change of administration in Washington following the presidential election of 1848. In 1852 he wrote the campaign biography of his old friend, Franklin Pierce. With Pierce's election as president, Hawthorne was rewarded in 1853 with the position of United States consul in Liverpool, England. In 1857 he resigned from this post and traveled in France and Italy. He and his family returned to The Wayside in 1860. Failing health (which biographer Edward Miller speculates was stomach cancer) began to prevent him from completing new writings. Hawthorne died in his sleep on May 19, 1864, in Plymouth, New Hampshire, while on a tour of the White Mountains with Pierce.

Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne had three children: Una, Julian, and Rose. Una may have suffered from mental illness and died young. Julian moved westward, served a jail term for embezzlement, and wrote a book about his father. Rose married George Parsons Lathrop, converted to Roman Catholicism and took her vows following Lathrop's death as a nun in the Dominican order. She founded a religious order, The Dominican Sisters of Hawthorne, to care for victims of incurable cancer.[4]

Writings

Hawthorne is best-known today for his many short stories (he called them "tales") and his four major romances of 1850‚Äď1860: The Scarlet Letter (1850), The House of the Seven Gables (1851), The Blithedale Romance (1852), and The Marble Faun (1860). (A previous book-length romance, Fanshawe, was published anonymously in 1828. Hawthorne would disown it in later life, going so far as to implore friends who still owned copies to burn it.)

Before publishing his first collection of tales in 1837, Hawthorne wrote scores of short stories and sketches, publishing them anonymously or pseudonymously in periodicals such as The New-England Magazine and The United States Democratic Review. (The editor of the Democratic Review, John L. O'Sullivan, was a close friend of Hawthorne's.) Only after collecting a number of his short stories into the two-volume Twice-Told Tales in 1837 did Hawthorne begin to attach his name to his works.

Much of Hawthorne's work is set in colonial New England, and many of his short stories have been read as moral allegories influenced by his Puritan background. "Ethan Brand" (1850) tells the story of a lime-burner who sets off to find the Unpardonable Sin, and in doing so, commits it. One of Hawthorne's most famous tales, ‚ÄúThe Birth-Mark‚ÄĚ (1843), concerns a young doctor who removes a birthmark from his wife's face, an operation which kills her. Other well-known tales include "Rappaccini's Daughter" (1844), "My Kinsman, Major Molineux" (1832), "The Minister's Black Veil" (1836), "Ethan Brand" (1850) and "Young Goodman Brown" (1835). "The Maypole of Merrymount" recounts a most interesting encounter between the Puritans and the forces of anarchy and hedonism. Tanglewood Tales (1853) was a re-writing some of the most famous of the ancient Greek myths in a volume for children, for which the Tanglewood estate in Stockbridge and music venue was named.

Recent criticism has focused on Hawthorne's narrative voice, treating it as a self-conscious rhetorical construction, not to be conflated with Hawthorne's own voice. Such an approach recognizes the artistry of the writer, complicating the long-dominant tradition of regarding Hawthorne as a gloomy moralist.

Hawthorne enjoyed a brief but intense friendship with Herman Melville beginning on August 5, 1850, when the two authors met at a picnic hosted by a mutual friend. Melville had just read Hawthorne's short story collection Mosses from an Old Manse, which Melville later praised in a famous review, "Hawthorne and His Mosses."[5] Subsequently the two struck up a correspondence initiated by Melville. Melville's letters to Hawthorne provide insight into the composition of how Melville developed his story of the great white whale and its nemesis Captain Ahab, but Hawthorne's letters to Melville did not survive. The correspondence ended shortly after Moby-Dick was published by Harper and Brothers.

When The Whale, first published in England in October 1851, was republished as Moby-Dick in New York one month later, Melville dedicated the book to Hawthorne, ‚Äúin appreciation for his genius.‚ÄĚ Similarities in The House of Seven Gables and the Moby-Dick stories are known and noted in literary and passing circles. The long lost responses to Melville would surely shed more light on this comparison.

Edgar Allan Poe, another contemporary, wrote important but unflattering reviews of both Twice-Told Tales and Mosses from an Old Manse. Hawthorne's opinions of Poe's work remains unknown.

The Scarlet Letter

Themes and analysis

The Scarlet Letter, published in 1850, is one of the few American world classics. It is generally considered to be Hawthorne's masterpiece. Set in Puritan New England in the seventeenth century, the novel tells the story of Hester Prynne, who gives birth after committing adultery, refusing to name the father. She struggles to create a new life of repentance and dignity. Throughout, Hawthorne explores the issues of grace, legalism, and guilt.

The Scarlet Letter is framed in an introduction (called "The Custom House") in which the writer, a stand-in for Hawthorne, purports to have found documents and papers that substantiate the evidence concerning Prynne and her situation. The narrator also claims that when he touched the letter it gave off a "burning heat… as if the letter were not of red cloth, but red hot iron." There remains no proof of a factual basis for the discovery in "the Custom House."

Plot summary

Hester Prynne, the story's protagonist, is a young married woman whose husband was presumed to have been lost at sea on the journey to the New World. She begins a secret adulterous relationship with Arthur Dimmesdale, the highly regarded town minister, and becomes pregnant with a daughter, whom she names Pearl. She is then publicly vilified and forced to wear the scarlet letter "A" on her clothing to identify her as an adulteress, but loyally refuses to reveal the identity of her lover. She accepts the punishment with grace and refuses to be defeated by the shame inflicted upon her by her society. Hester's virtue becomes increasingly evident to the reader, while the self-described "virtuous" community (especially the power structure) vilify her, and are shown in varying states of moral decay and self-regard. Hester only partially regains her community's favor through good deeds and an admirable character by the end of her life.

Dimmesdale, knowing that the punishment for his sin will be shame or execution, does not admit his relationship with Prynne. In his role as minister he dutifully pillories and interrogates Hester in the town square about her sin and the identity of the father. He maintains his righteous image, but internally he is dogged by his guilt and the shame for his weakness and hypocrisy. The work is tinged with a heavy irony, as among the townspeople he receives admiration while Hester receives social contempt, but for the reader the opposite is true. Finally, Prynne's husband, Roger Chillingworth, reappears without disclosing his identity to anyone but Hester. Suspecting the identity of Hester's partner, he becomes Dimmesdale's caretaker and exacts his revenge by exacerbating his guilt, while keeping him alive physically. Ultimately Dimmesdale‚ÄĒdriven to full public disclosure by his ill health‚ÄĒcollapses and dies, delivering himself from his earthly tormenter and personal anguish.

Influence

Nathaniel Hawthorne, with contemporaries Melville and Whitman, broke from European fictional conventions to forge a distinctly American literature. Hawthorne understood that America's religious past informed the nation's life and identity. He was absorbed by the enigma of evil and sought to clarify human responsibility within the context of social and moral expectations.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Nathaniel Hawthorne National Park Service. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Nathaniel Hawthorne, Malcolm Cowley (ed.), The Portable Hawthorne (The Viking Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0517478578).

- ‚ÜĎ Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, Journal of Sophia Hawthorne (January 14, 1851), Berg Collection, New York Public Library.

- ‚ÜĎ Rose Hawthorne (Mother Mary Alphonsa) 1851 - 1926 Dominican Sisters of Hawthorne. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Herman Melville, Hawthorne and His Mosses The Literary World (August 17 and 24, 1850). Retrieved October 27, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel, Millicent Bell (ed.). Nathaniel Hawthorne : Collected Novels: Fanshawe, The Scarlet Letter, The House of the Seven Gables, The Blithedale Romance, The Marble Faun. Library of America, 1983. ISBN 978-0940450080

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel, Malcolm Cowley (ed.). The Portable Hawthorne. The Viking Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0517478578

- Mellow, James R. Nathaniel Hawthorne in His Times. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1980. ISBN 0395276020

- Salwak, Dale. The Life of the Author: Nathaniel Hawthorne. Wiley-Blackwell, 2022. ISBN 978-1119771814

- Wineapple, Brenda. Hawthorne: A Life. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2004. ISBN 0812972910

External links

All links retrieved October 27, 2023.

- Hawthorne at Salem

- Hawthorne and His Mosses by Herman Melville, from The Literary World, August 17 and 24, 1850.

- Hawthorne By Henry James (1879).

- Works by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.