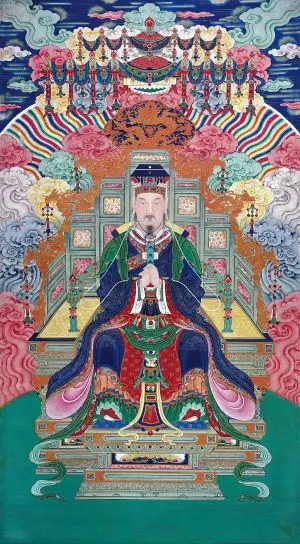

Jade Emperor

The Jade Emperor (玉皇 (Yù Huáng) or 玉帝 (Yù Dì)), known informally as Heavenly Grandfather (天公 (Tiān Gōng)) and formally as the Pure August Jade Emperor or August Personage of Jade (玉皇上帝 (Yu Huang Shangdi)) or 玉皇大帝 (Yu Huang Dadi),[1] is the ruler of Heaven (Tian) in Chinese mythology and is among the most important gods in the Daoist and folk pantheons. In his capacity as celestial ruler, the Jade Emperor is thought to govern Heaven and Earth, just as the earthly emperors once ruled over China. As such, he and his court (whose positions are filled by various gods and heavenly worthies) provide an explicit mythological parallel with the Chinese political hierarchy. Indeed, from the eleventh century onward, the divine sovereign was characterized as the official patron deity of the Chinese imperial family.

In addition to the myriad Chinese myths and popular tales that reference the deity, the Jade Emperor also figures into many religious rituals practiced by Daoists and adherents of Chinese folk religion (two categories that are often co-extensive).

Historical Origins

Given the Jade Emperor's lofty place in the pantheons of Daoist and folk religionists, it is intriguing to note that his cult and mythos lack the antiquity of many traditional practices. Historical records suggest that Yu Di was a relatively unimportant (or simply unknown) deity until the Tang period (618–907 C.E.),[2] and that it took the explicit patronage of a mortal emperor to invest the cult with the great popular importance that it later enjoyed. Specifically, Emperor Zhen Cong of Song (r. 997–1022) lent great prestige to his family name by claiming to receive spiritual revelations from the celestial court of the Jade Emperor. As such, the deity came to be seen as the patron of the royal family, and was memorialized with various honorific titles (such as "Pure August Emperor on High" and "Highest Author of Heaven, of the Whole Universe, of Human Destinies, of Property, of Rites, and of the Way, Very August One, Grand Sovereign of the Heavens"). Honored by this imperial sanction, the Jade Emperor thereafter came to be idealized by the practitioners of various Chinese religions.[3]

The Jade Emperor in Chinese Religious Practice

In keeping with his rulership over the cosmic hierarchy, the figure of Yu Di plays a pivotal role in many Chinese religious practices. In the Daoist tradition, the "barefoot masters" (a class of shamanistic "magicians" (fa shih)) are understood to derive their power from an initiatory audience with the Jade Emperor, where "the disciple introduces himself to the divine court and receives their investiture."[4] This audience is understood to secure them the authority to command various gods. Similar procedures are invoked during the rituals of the Daoist "priests" (道士 dao shi), whose religious practices are often predicated upon juxtaposing the mortal realm and that of the Jade Emperor. Schipper provides an excellent description of these ritual preparations in action:

In the middle of the space, right behind the central table, a painted scroll is hung, the only one that is not merely decorative and that has a real function in the ritual. The acolytes unroll it carefully, and then partially roll it up again. The only image in the painting is the character for "gate" (ch'üeh) which refers to the palace gate, the Golden Gate of the Jade Emperor (Yü-huang shangi-ti), head of the pantheon and highest of the gods, who is seated on the threshold of the Tao (87).[5]

Though the god is still central to many popular myths, he plays a less vital role in popular religion, likely due to his perceived distance from supplicants and the prevalence of Buddhist "High Gods" (such as Guanyin, Ju Lai (Shakyamuni Buddha), and Ēmítuó Fó (Amitabha Buddha)).[6] The one exception to this general trend can be seen in the god's central role in various popular New Year rituals.

New Year Rituals

- See also: Stove God

In general, Chinese New Year is a joyous festival of thanksgiving and celebration, wherein the old year is concluded, the new year is ushered in, the ancestors are revered, and the gods are petitioned for good fortune in the year to come. One important aspect of these proceedings is the belief that every family's actions are judged, with appropriate rewards and punishments meted out according to their conduct. The judgment itself, and the concomitant modification of mortal fates, is accomplished by the Jade Emperor. His verdict is determined by the testimony of the Stove God, a humble deity who lives in the family's kitchen for the entirety of the year, witnessing each filial act and minor transgression. As a result, one prominent New Year's Eve ritual involves bribing the Kitchen God with sweets (which are understood to either figuratively "sweeten his tongue" or to literally glue his lips shut).[7]

Later in the week, it is customary to celebrate the Jade Emperor's birthday, which is said to be the ninth day of the first lunar month. On this day, Daoist temples hold a Jade Emperor ritual (拜天公 bài tiān gōng, literally "heaven worship") at which priests and laymen prostrate themselves, burn incense, and make food offerings. One of the liturgies of propitiation offered to the celestial monarch attests to his perceived power:

Help the sick and all who suffer, protect the hermits against serpents and tigers, navigators against the fury of the waves, peaceable men against robbers and brigands! Drive far from us all contagion, caterpillars, and grasshoppers. Preserve us from drought, flood, and fire, from tyranny and captivity. Deliver from the hells those who are tormented there…. Enlighten all men with the doctrine that saves. Cause to be reborn that which is dead, and to become green again that which is dried up.[8]

The Jade Emperor in Chinese Mythology

Given that the Jade Emperor is most prominent in folk practices, it is unsurprising that he is a commonly recurring character in popular Chinese mythology. Indeed, virtually all Chinese myths, to the extent that they describe gods at all, will contain at least some reference to their celestial sovereign.[9] As such, only the most relevant or illustrative will be touched on below.

Origin Myth

Two strikingly incongruent accounts of the Jade Emperor's origins are found in China's textual and folk corpora: one popular, the other explicitly Daoist.

In the popular account, the Jade Emperor had originally been a mortal man named Zhang Denglai, a minor functionary in the nascent Zhou Dynasty who lost his life in the bloody civil war with the ruling Shang family (ca. 1100 B.C.E.). In the afterlife, he (alongside many other victims of this conflict) waited on the "Terrace of Canonization" for their appropriate posthumous rewards. These honors were being doled out by Jiang Ziya, the brave and resourceful commander who had led the rebel forces. Gradually each of the lofty positions in the celestial hierarchy was filled, with only the office of the Jade Emperor, "which Ziya was reserving for himself," remaining.

When offered the post, Jiang Ziya paused with customary courtesy and asked the people to “wait a second” (deng-lai) while he considered. However, having called out deng-lai, an opportunist, Zhang Denglai, hearing his name, stepped forward, prostrated himself, and thanked Jiang for creating him the Jade Emperor. Jiang, stupefied, was unable to retract his words; he was, however, quietly able to curse Zhang Denglai, saying “Your sons will become thieves and your daughters prostitutes.” Though this was not the ultimate fate of his daughters, many ribald stories are told about them.[10]

In marked contrast, the Daoist account sees the Jade Emperor earning his posting through exemplary personal piety. Born to a chaste empress after a vision of Laozi, the child was graced with unearthly compassion and charity. He devoted his entire childhood to helping the needy (the poor and suffering, the deserted and single, the hungry and disabled). Furthermore, he showed respect and benevolence to both men and creatures. After his father died, he ascended the throne, but only long enough to ascertain that everyone in his kingdom found peace and contentment. After that, he abdicated his post, telling his ministers that he wished to cultivate Dao on the Bright and Fragrant Cliff. It was only after extensive study and practice that he earned immortality (and, in the process, his posting at the head of the celestial hierarchy).[11]

Family

The Jade Emperor is thought to have familial connections with many deities in the popular pantheon, including his wife Wang Ma, and his many sons and daughters (such as Tzu-sun Niang-niang (a fertility goddess who grants children to needy couples), Yen-kuang Niang-niang (a goddess who provides individuals with good eyesight), and Zhi Nü (an unfortunate young lady who is described below)).[12]

The Princess and the Cowherd

In another story, popular throughout Asia and with many differing versions, the Jade Emperor has a daughter named Zhi Nü (Traditional Chinese: 織女; Simplified Chinese: 织女; literally: "weaver girl"), who is responsible for weaving colorful clouds in the heaven. Every day, the beautiful cloud maiden descended to earth with the aid of a magical robe to bathe. One day, a lowly cowherd named Niu Lang spotted Zhi Nü as she bathed in a stream. Niu Lang fell instantly in love with her and stole her magic robe, which she had left on the bank of the stream, rendering her unable to escape back to Heaven. When Zhi Nü emerged from the water, Niu Lang grabbed her and carried her back to his home.

When the Jade Emperor heard of this matter, he was furious but unable to intercede, since in the meantime his daughter had fallen in love and married the cowherd. As time passed, Zhi Nü grew homesick and began to miss her father. One day, she came across a box containing her magic robe that her husband had hidden. She decided to visit her father back in Heaven, but once she returned, the Jade Emperor summoned a river to flow across the sky (the Milky Way), which Zhi Nü was unable to cross to return to her husband. The Emperor took pity on the young lovers, and so once a year on the seventh day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, he allows them to meet on a bridge over the river.

The story refers to constellations in the night sky. Zhi Nü is the star Vega in the constellation of Lyra east of the Milky Way, and Niu Lang is the star Altair in the constellation of Aquila, west of the Milky Way. Under the first quarter moon (seventh day) of the seventh lunar month (around August), the lighting condition in the sky causes the Milky Way to appear dimmer, hence the story that the two lovers are no longer separated in that one particular day each year. The seventh day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar is a holiday in China called Qi Xi, which is a day for young lovers (much like Valentine's Day in the West). If it rains on that day, it is said to be Zhi Nü's grateful tears on the occasion of her too-brief reunion with her husband.[13]

The Zodiac

There are several stories as to how the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac were chosen. In one, the Jade Emperor, although having ruled Heaven and Earth justly and wisely for many years, had never had the time to actually visit the Earth personally. He grew curious as to what the creatures looked like. Thus, he asked all the animals to visit him in Heaven. The cat, being the most handsome of all animals, asked his friend the rat to wake him on the day they were to go to Heaven so he wouldn't oversleep. The rat, however, was worried that he would seem ugly compared to the cat, so he didn't wake the cat. Consequently, the cat missed the meeting with the Jade Emperor and was replaced by the pig. The Jade Emperor was delighted with the animals and so decided to divide the years up amongst them. When the cat learned of what had happened, he was furious with the rat and that, according to the story, is why cats and rats are enemies to this day.[14]

Notes

- ↑ As noted by Pas and Leung, these exalted titles were originally granted by imperial fiat as a means of increasing the god's prestige (185).

- ↑ H. Y. Feng's landmark article explores various Tang- and Song-era artistic works (including poetry and visual art) that evidence the god's existing mytho-religious cachet (244–247). While Goodrich cites several sources of preceding the Tang period, their paucity seems to imply a lack of universal acclamation (299).

- ↑ Stevens, 49; Pas and Leung, 184; Werner, 598–600. The last of these sources is notable for its entirely dismissive (even insulting) description of the deity's origins, which he claims were entirely fabricated following a disastrous military defeat. Indeed, he overtly states that "[the Jade Emperor] was born of a fraud, and came ready-made from the brain of an emperor" (599). While this view has held some scholarly currency (at least historically), Feng eloquently summarizes its fundamentally problematic nature: "It is not likely that an emperor who wished to cover up his defeat at the hands of barbarians by some divine ordinance would invent a deity totally unknown to his subjects. Maspero has said that ‘…with false visions even more than genuine ones it is essential to base them upon well-established belief…' and 'it is evident that, for the Emperor to have so definite a vision of his ancestor bringing him the order from the god, the god must already have ranked as a supreme deity in popular belief'" (242–244). His article, referenced above, provides an excellent summary of references predating the god's imperial patronage. Further, it must be acknowledged that any such references would have only survived in elite modes of communication (writings, paintings, etc.), which indicates that the overall level of popular support remains both unknown and unknowable.

- ↑ Schipper, 49.

- ↑ Wade-Giles romanization retained from the original text.

- ↑ Roberts, Chiao, and Pandey, 126. Indeed, their survey data ranked Yu Di as one of the most "remote"/"otherworldly" of all the deities in the popular pantheon (133–134).

- ↑ Chard, 13, 17; Newell, 64 ff 5.

- ↑ Goodrich, 300.

- ↑ The pantheons described in such tales often provide intimations of the theological beliefs of their writers, redactors, or transmitters. For instance, the Journey to the West, one of the most popular tales in the Chinese corpus, describes the Jade Emperor as subordinate to the Buddha (at least in terms of spiritual potency).

- ↑ Stevens, 50–51; Feng, 247–249.

- ↑ This tale is originally expounded in a scripture from the Tang or Song dynasties (Pas and Leung, 184). See also: Goodrich, 299; Werner, 599–600.

- ↑ Goodrich, 111, 121, 126.

- ↑ See Micha F. Lindemans, Chih Nu, Encyclopedia Mythica; Tai Chi Chaun Center, The Herd Boy and the Weaving Girl, August 1, 2001. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ↑ In another version, the Jade Emperor arranges a swimming race between various terrestrial animals to see which ones will earn the honor of being commemorated in the zodiac. See Florence Cardinal, The Chinese Zodiac, suite101.com, February 2, 1999; see also Topmarks Education, Chinese Zodiac, for a third variant.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chard, Robert L. "Rituals and Scriptures of the Stove Cult." In Ritual and Scripture in Chinese Popular Religion: Five Studies, edited by David Johnson. Berkeley, CA: Chinese Popular Culture Project, 1995. ISBN 0962432733.

- Feng, H. Y. "The Origin of Yu Huang." Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 1:2 (July 1936: 242–250.

- Fitzgerald, C. P. China: A Short Cultural History. London: Cresset Library, 1986. ISBN 0091687519.

- Goodrich, Anne S. Peking Paper Gods: A Look at Home Worship. Monumenta Serica Monograph Series XXIII. Nettetal, Germany: Steyler-Verlag, 1991. ISBN 380500284X.

- Hansen, Valerie. Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127–1276. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990. ISBN 0691055599.

- Kohn, Livia. Daoism and Chinese Culture. Cambridge, MA: Three Pines Press, 2001. ISBN 1931483000.

- Newell, Venetia. "A Note on the Chinese New Year Celebration in London and Its Socio-Economic Background." Western Folklore 48:1 (January 1989): 61–66.

- Pas, Julian F., and Man Kam Leung. "Jade Emperor." In Historical Dictionary of Taoism. Lanham, MD, and London: Scarecrow Press, 1998. ISBN 0810833697.

- Roberts, John M, Chien Chiao, and Triloki N. Pandey. "Meaningful God Sets from a Chinese Personal Pantheon and a Hindu Personal Pantheon." Ethnology 14:2 (April 1975): 121–148.

- Robinet, Isabelle. Taoism: Growth of a Religion. Stanford University Press, 1997 [original French version, 1992]. ISBN 0804728399.

- Schipper, Kristopher. The Taoist Body. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993 [original French version, 1982]. ISBN 0520082249.

- Stevens, Keith G. Chinese Mythological Gods. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0195919904.

- von Glahn, Richard. The Sinister Way: The Divine and Demonic in Chinese Religious Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. ISBN 0520234081.

- Werner, E. T. C. "Jade Emperor." In A Dictionary of Chinese Mythology, 341–352. Wakefield, NH: Longwood Academic, 1990. ISBN 0893410349.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.