Harpsichord

A harpsichord is any of a family of European keyboard instruments, including the large instrument currently called a harpsichord, but also the smaller virginals, the muselar virginals and the spinet. All these instruments generate sound by plucking a string rather than striking one, as in a piano or clavichord. The harpsichord family is thought to have originated when a keyboard was affixed to the end of a psaltery, providing a mechanical means to pluck the strings. The type of instrument now usually called a harpsichord in English is generally called a clavicembalo or simply cembalo in Italian, and this last word is generally used in German as well. The typical French word is clavecin. Confusingly, the most commonly used Spanish word for a harpsichord is clavicordio, leading to confusion with the clavichord. Accordingly, in musical circles the Italian or, more commonly, the French word is used by Spanish speakers.

A musician who plays the harpsichord is called a harpsichordist.

History

The origin of the harpsichord is obscure, but is known to have begun some time during the high or late Middle Ages. The earliest written references to the instrument date from the 1300s and it is possible that the harpsichord was indeed invented in that century. This was a time in which advances in clockwork and other forms of early pre-modern machinery were being made and thus a likely time for the invention of those mechanical aspects that distinguish a harpsichord from a psaltery. A Latin manuscript work on musical instruments by Henri Arnault de Zwolle, c. 1440, includes detailed diagrams of a small harpsichord and three types of jack action.

Italy

The earliest complete harpsichords still preserved come from Italy, the oldest specimen being dated to 1521. The Royal Academy of Music in London, has an instrument of a curious upright form, which may be older; unfortunately, it lacks the action. These early Italian instruments can however shed no light on the origin of the harpsichord, as they represent an already well-refined form of the instrument. The Italian harpsichord makers made single-manual instruments with a very light construction and relatively little string tension. This design persisted with little alteration among Italian makers for centuries. The Italian instruments are considered pleasing but unspectacular in their tone and serve well for accompanying singers or other instruments. Towards the end of the historical period larger and more elaborate Italian instruments were built, notably by Bartolomeo Cristofori.

Flanders

A revolution in harpsichord construction took place in Flanders some time around 1580 with the work of Hans Ruckers and his descendants, including Ioannes Couchet. The Ruckers harpsichord was more solidly constructed than the Italian was. Because they used longer strings (always with the basic two sets of strings; usually one 8-foot and a 4-foot, but occasionally both at 8-foot pitch), greater string tension, and a heavier case, as well as a very slender and responsive spruce soundboard, the tone was more sustaining than with the Italian harpsichord, and was widely emulated by harpsichord builders in most other nations. The Flemish makers also developed a style of two-manual harpsichord, which was initially used merely to permit easy transposition (at the interval of a fourth) rather than to increase the expressive range of the instrument. However, later in the seventeenth century the additional manual was also used for contrast of tone with the ability to couple the registers of both manuals for a fuller sound. The Flemish harpsichords were often elaborately painted and decorated.

France

The Flemish instrument received further development in 18th century France, notably with the work of the Blanchet family and their successor Pascal Taskin. These French instruments imitated the Flemish design, but were extended in range, from about four to about five octaves. In addition, two-manual French instruments used their manuals to vary the combination of stops being used (that is, strings being plucked) rather than for transposition. The eighteenth century French harpsichord is often considered one of the pinnacles of harpsichord design, and it is widely adopted as a model for the construction of modern instruments.

A striking aspect of the eighteenth-century French tradition was its near-obsession with the Ruckers harpsichords. In a process called grand ravalement, many of the surviving Ruckers instruments were disassembled and reassembled, with new soundboard material and case construction adding an octave to their range. It is considered likely that many of the harpsichords claimed at the time to be Ruckers restorations are fraudulent, though they are superb instruments in their own right. A more basic process was the so-called petit ravalement, in which the keyboards and string sets, but not the case, were modified.

England

The harpsichord was important in England during the Renaissance for the large group of major composers who wrote for it, but apparently many of the instruments of the time were Italian imports. Harpsichord building in England only achieved great distinction in the 18th century with the work of two immigrant makers, Jacob Kirckman (from Alsace) and Burkat Shudi (from Switzerland). The harpsichords by these builders, built for a prosperous and expanding social elite, were notable for their powerful tone and exquisite veneered cases. The sound of Kirckman and Shudi harpsichords has impressed many listeners, but the feeling that it overpowers the music has led to very few modern instruments being modeled on them. The Shudi firm was passed on to Shudi's son-in-law John Broadwood, who adapted it to the manufacture of pianos and became a leading creative force in the development of that instrument.

Germany

German harpsichord makers roughly followed the French model, but with a special interest in achieving a variety of sonorities, perhaps because, some of the most eminent German builders were also builders of pipe organs. Some German harpsichords included a choir of 2-foot strings (that is, strings pitched two octaves above the primary set). A few even included a 16-foot stop, pitched an octave below the main 8-foot choirs. One still-preserved German harpsichord even has three manuals to control the many combinations of strings that were available. The 2-foot and 16-foot stops of the German harpsichord are not particularly favored among harpsichordists today, who tend to prefer the French type of instrument.

Obsolescence and revival

At the peak of its development, the harpsichord lost favor to the piano. The piano quickly evolved away from its harpsichord-like origins, and the accumulated traditional knowledge of harpsichord builders gradually dissipated.

In the early twentieth century, an awakening interest in historically informed performance, with the renowned, energetic and now sometimes controversial Wanda Landowska as its banner-carrier, led to the revival of the harpsichord. In the early decades of the revival, the harpsichords that were built were heavily influenced by the modern grand piano, notably in using heavy metal frames far sturdier than would be needed to support the tension of harpsichord strings. Such was the instrument that the Parisian piano makers Pleyel build for Mme Landowska. Builders typically included a 16-foot stop in these instruments to bolster the sound, following a (relatively unusual) practice of 18th century German builders.

Starting around the middle of the century, harpsichord construction took a new turn when a new generation of builders sought to imitate the designs and construction methods of earlier centuries. This movement was led by (among others) Frank Hubbard and William Dowd, working in Boston, Arnold Dolmetsch, settled in Surrey in the UK and Martin Skowroneck, working in Bremen, Germany. These builder-scholars took apart and inspected many old instruments and consulted the written material on harpsichords from the historical period. Most harpsichords built nowadays are based on the rediscovered principles of the old makers, and this includes harpsichords that have been assembled from kits sold by modern harpsichord manufacturing companies.

Action

The action is similar in all harpsichords:

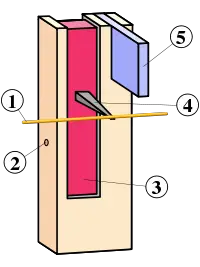

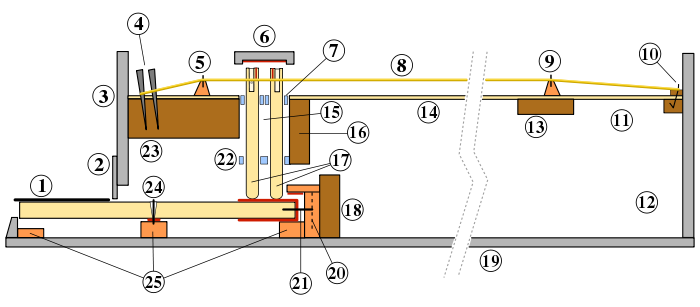

- The keylever is a simple pivot, which rocks on a pin passing through a hole drilled through it.

- The jack is a thin, rectangular piece of wood which sits upright on the end of the keylever, held in place by the guides (upper and lower) which are two long pieces of wood with holes through which the jacks can pass.

- In the jack, a plectrum juts out almost horizontally (normally the plectrum is angled upwards a tiny amount) and passes just under the string. Historically, plectra were normally made of crow quill or leather, though most modern harpsichords use a plastic (delrin or celcon) instead.

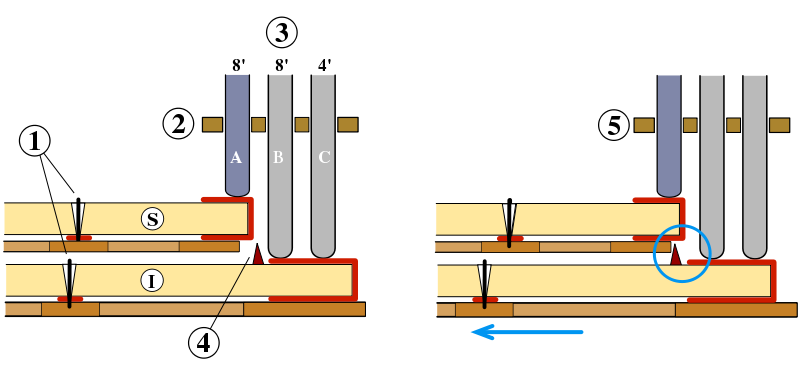

- When the front of the key is pressed (2), the back is lifted up, the jack is raised, and the plectrum plucks the string (3).

- Upon lowering the key, the jack falls back down under its own weight, and the plectrum pivots backwards to allow it past the string (4). This is made possible by having the plectrum held in a tongue, which is attached with a hinge and a spring to the body of the jack.

- At the top of the jack, a damper of felt sticks out and keeps the string from vibrating when the key is not depressed (1).

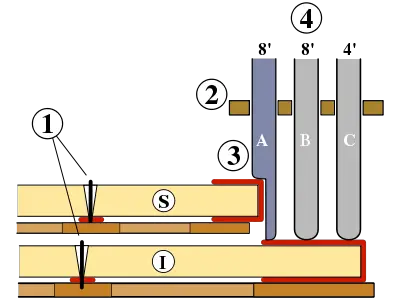

Controlling multiple choirs of strings

One respect in which harpsichords varied greatly was in the mechanisms that controlled which choirs of strings would sound when the keys were pressed. In general, a set of strings can be "turned off" by moving the upper register (through which its jacks slide) sideways a bit, so that the plectra no longer touch the strings. In simpler instruments, this function was performed directly by hand, but as the harpsichord evolved various inventions arose making it easier to change the registration, for example with levers next to the keyboard, knee levers, or pedals.

In instruments that had more than one manual (keyboard), makers often produced arrangements whereby the notes of one manual could optionally be sounded with the other manual. The most flexible system was the French shove coupler, in which the lower manual could slide forward and backward, and in the backward position "dogs" attached to the upper surface of the lower manual would engage the lower surface of the upper manual's keys, causing them to play. Depending on choice of keyboard and coupler position, the player could select the set of jacks labeled A, or B and C, or all three.

The English dogleg jack system was less flexible, in that the manuals were immobile. The dogleg shape of the set of jacks labeled A permitted A to be played by either keyboard, but the lower manual necessarily played all three sets, and could not play just B and C as in the French shove coupler.

Variants

While the terms used to denote various members of the family have been quite standardized today, in the harpsichord's heyday, this was not the case.

Harpsichord

In modern usage, a harpsichord can either mean all the members of the family, or more specifically, the grand-piano-shaped member, with a vaguely triangular case accommodating long bass strings at the left and short treble strings at the right; characteristically, the profile is more elongated than that of a modern piano, with a sharper curve to the bentside.

A harpsichord can have from one to three, and occasionally even more, strings per note. Often one is at four-foot pitch, an octave higher than the normal eight foot pitch. When there are two eight foot choirs, typically one has a plucking point closer to the bridge, creating a more "nasal" tone quality emphasizing the upper harmonics.

Single manuals, or keyboards, are common, especially in Italian harpsichords. Double manuals, which permit greater control over which strings are sounded, are found in the more elaborate instruments. There are a few examples of three manual German instruments.

Virginals

The virginal or virginals is a smaller and simpler rectangular form of the harpsichord (that looks somewhat like a clavichord), with only one string per note running parallel to the keyboard on the long side of the case. Identified by this name by 1460, it was played either in the lap, or more commonly, rested on a table.[1]While the name apparently comes from the same root as the adjective "virginal," the reason for this name is obscure. Note that the word "virginal" in Elizabethan times was often used to designate any kind of harpsichord; thus the masterworks of William Byrd and his contemporaries were often played on full-size, Italian-style harpsichords and not just on the virginals as we call it today. Virginals are described either as spinet virginals (the usual type) or muselar virginals.

Spinet virginals

In spinet virginals, the keyboard is placed on the left, and the strings are plucked at one end as in other members of the harpsichord family. This is the more common arrangement, and an instrument described simply as a "virginal" is likely to be a spinet virginal.

Muselar virginals

In muselar virginals, or muselars, the keyboard is placed to the right or in the center so that the strings are plucked in the middle of their sounding length. This gives a warm and rich sound, but at a price: the action for the left hand is inevitably placed in the middle of the instrument's sounding board, with the result that any mechanical noise from this action is amplified. An 18th century commentator said that muselars "grunt in the bass like young pigs." In addition to mechanical noise, the central plucking point in the bass makes repetition difficult, because the motion of the still-sounding string interferes with the ability of the plectrum to connect again. Thus the muselar was better suited to chord-and-melody music without complex left hand parts.

Muselars were popular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but they fell out of use in the eighteenth century.

Spinet

Finally, a harpsichord with the strings set at an angle to the keyboard (usually of about 30 degrees) is called a spinet. In such an instrument, the strings are too close to fit the jacks between them in the normal way; instead, the strings are arranged in pairs, the jacks are placed in the large gaps between pairs, and they face in opposite directions, plucking the strings adjacent to the gap.

Clavicytherium

A clavicytherium is a harpsichord that is vertically strung. Few were ever made. The same space-saving principle was later embodied in the upright piano. Its action was modified to make the vertical form possible simply by modifying the shape of the jacks so that the body curved like a quarter circle. An example has survived from the late fifteenth century (found at the Royal College of Music in London), and they were used until the eighteenth century.[1]

Variations

Unsurprisingly, for an instrument that was produced in large numbers for over three centuries, there is a great deal of variation between harpsichords.

In addition to the varied forms that the instrument can take and the different dispositions, or registrations, that can be fitted to a harpsichord as mentioned above, the range can vary greatly.

Generally, earlier harpsichords have smaller ranges and later ones larger, though there are frequent exceptions. In general, the largest harpsichords have a range of just over five octaves and the smallest have under four. Usually, the shortest keyboards were given extended range using the method of the "short octave."

Several harpsichords with heavily modified keyboards, such as the archicembalo, were built in the sixteenth century to accommodate variant tuning systems demanded by compositional practice and theoretical experimentation.

Music for the harpsichord

Historic

The first music written specifically for solo harpsichord came to be published around the middle of the sixteenth century. Composers who wrote solo harpsichord music were numerous during the whole Baroque era in Italy, Germany and, above all, France. Favorite genres for sole harpsichord composition included the dance suite, the fantasia, and the fugue. Besides solo works, the harpsichord was widely used for accompaniment in the basso continuo style (a function it maintained in opera even into the 19th century). Well into the 18th century, the harpsichord was considered to have advantages and disadvantages with respect to the piano.

Through the nineteenth century, the harpsichord was ignored by composers, the piano having supplanted it. In the twentieth century, however, with increasing interest in early music and composers seeking new sounds, pieces began to be written for it once more. Concertos for the instrument were written by Francis Poulenc (the Concert champĂȘtre, 1927-1928), Manuel de Falla and, later, by Henryk GĂłrecki, Philip Glass and Roberto Carnevale. Bohuslav MartinĆŻ wrote both a concerto and a sonata for it, and Elliott Carter's Double Concerto is for harpsichord, piano and two chamber orchestras. In chamber music, György Ligeti has written a small number of solo works for the instrument (including "Continuum") while Henri Dutilleux's "Les Citations" (1991) is a piece for harpsichord, oboe, double bass and percussions. Both Dmitri Shostakovich (Hamlet, 1964) and Alfred Schnittke (Symphony No.8, 1998) used the harpsichord as part of the orchestral texture. More recently harpsichordist Hendrik Bouman has composed in the seventeenth and eighteenth century style 75 pieces of which 37 compositions are for solo harpsichord, 2 compositions are of harpsichord concerti, 2 compositions feature obbligato harpsichord and 36 composition include harpsichord in the basso continuo in his chamber music and orchestral music.

Popular music

Like almost all instruments of classical music, the harpsichord has been adapted for popular work. The number of such uses is vast; for a partial list, see harpsichord in popular culture.

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 Robert Dearling, The Ultimate Encyclopaedia of Musical Instruments (Carlton Books, 1996, ISBN 1858681855).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- de Saint-Lambert, Michel and Rebecca Harris-Warrick. Principles of the harpsichord. Cambridge; NY: Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 0521252768

- Hubbard, Frank, Three Centuries of Harpsichord Making. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967. ISBN 0674888456 This is an authoritative survey of how early harpsichords were built and how the harpsichord evolved over time in different national traditions.

- Kottick, Edward L., The harpsichord owner's guide: a manual for buyers and owners. Cahpel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. ISBN 0807817457

- Palmer, Larry, Harpsichords in America: a 20th century revival. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0253327105

External links

All links retrieved June 25, 2024.

- Multilingual harpsichord lexicon

- Hear the sound of various harpsichords

- British Harpsichord Society

- Harpsichord Photo

- Ernest Miller Harpsichords: Creations in the French and Flemish Traditions.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.