Family therapy is a type of psychotherapy that focuses on the relationships among family members, regarding the family as a whole as the "patient" or "client." It also regards the family as more than just the sum of the individual members, using models based on systems approach, such as used in cybernetics or game theory. The goal of family therapy is to return the family as a whole to health, such that each family member is emotionally connected to the family and is embraced as a fully functioning member while at the same time is differentiated as an individual, able to pursue and achieve personal goals.

Family therapy emerged from and made a decisive break from the dominant Freudian tradition centered on the dyadic relationship between patient and doctor, in which psychopathology was thought to be within the individual. In the new understanding, the relationship of every member in the family is an important influence on the health of the entire system, which then influences the health of each member. This approach recognizes that human beings are essentially social beings, that relationships with others are key to our psychological health, and that the core foundation of social relationships is found in the family. Still, however, understanding how that core family functions in a healthy manner allowing each member to achieve optimal health, and how to restore the many dysfunctional families to a state of health, is a tremendous challenge. While family therapy has made great advances using understandings from many disciplines, the spiritual aspects of human nature have not yet been included. To achieve healthy families, the spiritual element is also important.

Introduction

Family therapy, also referred to as couple and family therapy and family systems therapy (and earlier generally referred to as marriage therapy), is a branch of psychotherapy that works with families and couples in intimate relationships to nurture change and development. It tends to view these in terms of the systems of interaction between family members. It emphasizes family relationships as an important factor in psychological health. As such, family problems have been seen to arise as an emergent property of systemic interactions, rather than to be blamed on individual members.

Family therapists may focus more on how patterns of interaction maintain the problem rather than trying to identify the cause, as this can be experienced as blaming by some families. It assumes that the family as a whole is larger than the sum of its parts.

Most practitioners are "eclectic," using techniques from several areas, depending upon the client(s). Family therapy practitioners come from a range of professional backgrounds, and some are specifically qualified or licensed/registered in family therapy (licensing is not required in some jurisdictions and requirements vary from place to place). In the UK, family therapists are usually psychologists, nurses, psychotherapists, social workers, or counselors who have done further training in family therapy, either a diploma or an M.Sc.

Family therapy has been used effectively where families, and or individuals in those families experience or suffer:

- Serious psychological disorders (such as schizophrenia, addictions, and eating disorders)

- Interactional and transitional crises in a family’s life cycle (such as divorce, suicide attempts, dislocation, war, and so forth)

- As a support of other psychotherapies and medication

The goal of family therapy is to return the family as a whole to health, such that each family member is emotionally connected to the family and embraced as a fully functioning member while at the same time is differentiated as an individual, able to pursue and achieve personal goals.

History

The origins and development of the field of family therapy are to be found in the second half of the twentieth century. Prior to the Second World War, psychotherapy was based on the Freudian tradition centered on the dyadic relationship between patient and doctor. Pathology was thought to be within the individual. It was not until around the 1950s that insights started to come out of work done with families of schizophrenic patients. The change of perspective away from Freudian theory and toward a systems approach has been unfolding since then.

The figures who seem to have had the most impact on the family field in its infancy were, oddly enough, not so much psychotherapists but scientists such as information theorist Claude Shannon, cyberneticist Norbert Wiener, and general systems theorist John von Neuman. One must add to this list George Bateson, whose synthesizing genius showed how ideas from such divergent sources could be useful to the understanding of communication processes, including those associated with psychopathology.

Murray Bowen

Interest in the mental illness of schizophrenia, in the 1950s, prompted financial resources for research from the National Institute of Mental Health. A new wing was designed at Bethesda, Maryland, and designated for psychiatric research. Murray Bowen was hired at this new research facility from his post at the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas. He was of the opinion that the predominant theory in practice, the Freudian theory, was too narrow. ‚ÄúHe had an idea that the basic unit of emotional functioning might not be the individual, as previously thought, but the nuclear family.‚ÄĚ[1] Based on this, Bowen suggested that a new way of looking at and analyzing the interactions within families was needed. He called this method ‚Äúsystems thinking.‚ÄĚ

Bowen‚Äôs theory became a catalyst for the paradigm shift taking place in the field of mental health and family therapy. Some of the underlying assumptions are based on a few pivotal concepts. An example of one such principle is the ‚Äústruggle that arises out of the need to strike a balance between two basic urges: The drive towards being an individual‚ÄĒone alone, autonomous‚ÄĒand the drive towards being together with others in relationship.‚ÄĚ Bowen‚Äôs theory focused on the need for the two forces to find a point of balance. The balancing point centers on the role of individuals in families and how to manage their ‚Äútogetherness.‚ÄĚ As individuals become more emotionally mature, their ability to find the proper balance in the family increases.

Another underlying assumption in Bowen‚Äôs theory rests on the concept that ‚Äúindividuals vary in their ability to adapt‚ÄĒthat is, to cope with the demands of life and to reach their goals.‚ÄĚ It is also important to mention the importance of ‚Äútriangulation‚ÄĚ when considering Bowen‚Äôs theory. Essentially this is based on his analysis that "human emotional systems are built on triangles.‚ÄĚ Essentially this means that whenever two family members have problems in their relationship, they add a third person to form a triangle. This triangle is a more stable arrangement than the pair in conflict.

Gregory Bateson

Gregory Bateson was one of the first to introduce the idea that a family might be analogous to a homeostatic or cybernetic system.[2] Bateson's work grew from his interest in systems theory and cybernetics, a science he helped to create as one of the original members of the core group of the Macy Conferences.

The approach of the early family researchers was analytical and, as such, focused on the patient only. It was thought that the symptoms were the result of an illness or biological malfunction. The people charged with a cure were doctors and the setting for their work was a hospital. The psychodynamic model of the nineteenth century added trauma from a patient‚Äôs past to the list of possible causes. To put it simply, distress was thought to arise from biological or physiological causes or from repressed memories. Family members and others in the individual‚Äôs social circle were not allowed anywhere near, as they might ‚Äútaint‚ÄĚ the pureness of the therapy. It was by chance that Bateson and his colleagues came across the family‚Äôs role in a schizophrenic patient‚Äôs illness.

The use of the two room therapy model introduced a new ‚Äúwindow‚ÄĚ to see through. By watching families interact with the patient in a room separated by a one way window, it became clear that patients behaved differently when in the dynamics of their family. The interactions within the family unit created ‚Äúcausal feedback loops that played back and forth, with the behavior of the afflicted person only part of a larger, recursive dance.‚ÄĚ

Once this "Pandora’s Box" was open, other researchers began to experiment and find similar outcomes. In the 1960s, many articles poured out with examples of successful strategies of working with schizophrenic patients and their family members. The mother’s role was usually considered to play a central role in the breakdown of communication and the underlying controls that were in place.

The concept of ‚Äúdouble bind‚ÄĚ hypothesis was coined in Bateson‚Äôs famous paper, ‚ÄúToward a Theory of Schizophrenia,‚ÄĚ published in 1956. ‚ÄúDouble bind‚ÄĚ describes a context of habitual communication impasses imposed on one another by persons in a relationship system. This form of communication depicts a type of command that is given on one level and nullified on another level. It is a paradox that creates constant confusion and unresolved interpretations. An example is when an irritated mother tells her child to go to bed so they can get enough sleep for school tomorrow when, in fact, she just wants some private space or a break from the child. Depending on the level of deceit (often called a white lie) both parties are unable to acknowledge what the other is really saying or feeling. This is a highly simplified example, but illustrates how commonly the ‚Äúdouble bind‚ÄĚ is used, even in ‚Äúnormal‚ÄĚ family life.

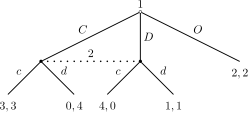

The original framework for the ‚Äúdouble bind‚ÄĚ was a two-person or ‚Äúdyadic‚ÄĚ arrangement. Criticism of the dyadic approach appeared in an essay by Weakland titled, "The Double Bind: Hypothesis of Schizophrenia and Three Party Interaction,‚ÄĚ in 1960. Further articles in the 1970s, by both Weakland and Bateson, suggest that this concept referred to a much broader spectrum than schizophrenias. Bateson began to formulate a systems approach which factored in the relationships of family as a coalition. He used an analogy from game theory that described repeated patterns found in families with a schizophrenic member. The pattern that emerged was that ‚Äúno two persons seemed to be able to get together without a third person taking part.‚ÄĚ

The game theory Bateson drew from was based on Theory of Games by von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern. In this theory, the tendency of ‚Äúwinning‚ÄĚ personalities is to form coalitions. This rule, however, did not apply when the group had three or five members. Bateson found in his research that ‚Äúno two members ever seemed able to get together in a stable alignment‚ÄĚ in schizophrenic families.

The next logical progression from this process was the development of consideration of families as a ‚Äúcybernetic‚ÄĚ system. In Strategies of Psychotherapy, Haley agreed with Bateson‚Äôs conclusion that schizophrenic families exhibit consistent use of ‚Äúdisqualifying messages‚ÄĚ or ‚Äúdouble bind‚ÄĚ communication style. He added to this the idea that ‚Äúpeople in a family act to control the range of one another‚Äôs behavior.‚ÄĚ He based much of his argument for the two levels of disconnected communication and need to control on Russell‚Äôs ‚Äútheory of logical types.‚ÄĚ

Salvadore Minuchin

Salvadore Minuchin published Families and Family Therapy in 1974. His theory is based on ‚Äústructural family therapy,‚ÄĚ which is a process that considers the feedback between circumstances and the shift that occurs following the feedback.[3] In other words, ‚ÄúBy changing the relationship between a person and the familiar context in which he functions, one changes his objective experience.‚ÄĚ The therapist enters into the family setting and becomes an agent of change. The introduction of this new perspective begins a transforming and healing process as each member of the family adjusts their world view vis-√†-vis the new information.

Minuchin‚Äôs structural family therapy considered this mechanism with the addition of also recognizing that the family past manifests in the present. He wisely set out to benchmark a ‚Äúmodel of normality,‚ÄĚ derived from examination of families in different cultures. His goal was to identify healthy patterns shared by all families without regard of their culture. Minuchin wrote, that in all cultural contexts ‚Äúthe family imprints its members with selfhood.‚ÄĚ The changes brought about in the Western cultural sphere since the urban industrial revolution has brought forced, rapid change in the patterns of common family interactions. Economic demands have placed both parents out of the home leaving children to be raised at school, day care, or by peers, television, internet, and computer games. ‚ÄúIn the face of all these changes, modern man still adheres to a set of values." He went on to say that these changes actually make the role of the family as a support even more vital to current society than ever before. When he was writing this book, the forces of change he was referring to was the women‚Äôs liberation movement and conflicts from the ‚Äúgeneration gap.‚ÄĚ The world has continued to unfold since then, in a way that even Minuchen would not have been able to foresee. Despite this, his work has been and continues to be relevant and important to inform the efforts of practitioners in the field today.

Methodology

Family therapy uses a range of counseling and other techniques including:

- Psychotherapy

- Systems theory

- Communication theory

- Systemic coaching

The basic theory of family therapy is derived mainly from object relations theory, cognitive psychotherapy, systems theory, and narrative approaches. Other important approaches used by family therapists include intergenerational theory (Bowen systems theory, Contextual therapy), EFT (emotionally focused therapy), solution-focused therapy, experiential therapy, and social constructionism.

Family therapy is really a way of thinking, an epistemology rather than about how many people sit in the room with the therapist. Family therapists are relational therapists; they are interested in what goes between people rather than in people.

A family therapist usually meets several members of the family at the same time. This has the advantage of making differences between the ways family members perceive mutual relations as well as interaction patterns in the session apparent both for the therapist and the family. These patterns frequently mirror habitual interaction patterns at home, even though the therapist is now incorporated into the family system. Therapy interventions usually focus on relationship patterns rather than on analyzing impulses of the unconscious mind or early childhood trauma of individuals, as a Freudian therapist would do.

Depending on circumstances, a therapist may point out to the family interaction patterns that the family might have not noticed; or suggest different ways of responding to other family members. These changes in the way of responding may then trigger repercussions in the whole system, leading to a more satisfactory systemic state.

Qualifications

Counselors who specialize in the area of family therapy have been called Marriage, Family, and Child Counselors. Today, they are better known as Marriage and Family Therapists, (MFTs) and work variously in private practice, in clinical settings such as hospitals, institutions, or counseling organizations. MFTs are often confused with Clinical Social Workers (CSWs). The primary difference in these two professions is that CSWs focus on social relationships in the community as a whole, while MFTs focus on family relationships.

A master's degree is required to work as an MFT. Most commonly, MFTs will first earn a B.S. or B.A. degree in psychology, and then spend two to three years completing a program in specific areas of psychology relevant to marriage and family therapy. After graduation, prospective MFTs work as interns. Requirements vary, but in most states in the U.S., about 3000 hours of supervised work as an intern are needed to sit for a licensing exam. MFTs must be licensed by the state to practice. Only after completing their education and internship and passing the state licensing exam can they call themselves MFTs and work unsupervised.

There have been concerns raised within the profession about the fact that specialist training in couples therapy‚ÄĒas distinct from family therapy in general‚ÄĒis not required to gain a license as an MFT or membership of the main professional body (American Association of Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT).[4]

Since issues of interpersonal conflict, values, and ethics are often more pronounced in relationship therapy than in individual therapy, there has been debate within the profession about the values implicit in the various theoretical models of therapy and the role of the therapist’s own values in the therapeutic process, and how prospective clients should best go about finding a therapist whose values and objectives are most consistent with their own.[5] Specific issues that have emerged have included an increasing questioning of the longstanding notion of therapeutic neutrality, a concern with questions of justice and self-determination,[6] connectedness and independence,[7] "functioning" versus "authenticity," and questions about the degree of the therapist’s "pro-marriage/family" versus "pro-individual" commitment.[8]

Cultural considerations

The basics of family systems theory were designed primarily with the ‚Äútypical American nuclear family‚ÄĚ in mind. There has been growing interest in how family therapy theories translate to other cultures. Research on the assimilation process of new immigrants into the United States has informed research on family relationships and family therapy. Focus has been turned toward the largest population of immigrants, coming into the United States from Mexico and Central America. Asian and specifically Chinese immigrants also have received significant attention.

Parenting style differences between Mexican-descent (MD) and Caucasian-non-Hispanic (CNH) families have been observed, with parenting styles of the mother and father figures also exhibiting differences.[9]

Within Mexican American household, sisters and brothers are a prominent part of family life. According to U.S. census data, Mexican American families have more children than their non-Latino counterparts. There is a strong emphasis on family loyalty, support, and interdependence that is translated as ‚Äúfamilismo‚ÄĚ or familism. ‚ÄúGender norms in Mexican American families may mean that familism values are expressed differently by girls versus boys. Familism is a multidimensional construct that includes feelings of obligation, respect and support.‚ÄĚ[10] Girls usually express their role by spending time with the family. Boys, on the other hand, seek out achievements outside of the home.

At the University of Tokyo, an article on family therapy in Japan was translated for the American Psychologist, in January 2001. The abstract begins by explaining that family therapy has developed since the 1980s. The authors wrote, ‚Äúwe briefly trace the origins of these (family psychology and family therapy) movements. Then, we explain how these fields were activated by the disturbing problem of school refusal.‚ÄĚ[11] School refusal is a term used in the Japanese society to describe children that stay home from school with the parent‚Äôs knowledge. It implies something different from school phobia or truancy. The number of these children has been increasing each year. Parents, when surveyed, often cited the Japanese methodology of standardizing behavior and producing ‚Äúgood boys and girls.‚ÄĚ The expectations and pressures for children‚Äôs success are extremely high. The mothers are largely stay-at-home and given the responsibility of ensuring the child becomes successful. In many cases, the mother does not have the tools to fully accomplish this.

This study concludes with a plan to develop a wide range of supportive programs and services to empower the family using models developed in the United States. Furthermore, fathers are encouraged to play a bigger role in the family and Japanese companies are being asked to promote training on the job.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Roberta M. Gilbert, Extraordinary Relationships: A New Way of Thinking About Human Interactions (New York: Wiley and Sons, 1992, ISBN 047134690x).

- ‚ÜĎ L. Hoffman, Foundations of Family Therapy (Basic Books, 1981).

- ‚ÜĎ Salvador Minuchin, Families and Family Therapy (Harvard University Press, 1974, ISBN 0674292367).

- ‚ÜĎ W. Doherty, Bad Couples Therapy and How to Avoid Doing It Psychotherapy Networker, 26(2002): 26-33.

- ‚ÜĎ J. Wall, T. Needham, D.S. Browning, and S. James, The Ethics of Relationality: The Moral Views of Therapists Engaged in Marital and Family Therapy, Family Relations, 48, 2(1999): 139-149.

- ‚ÜĎ Richard Melito, Values in the role of the family therapist: Self determination and justice, Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29(1) (2003): 3-11. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Blaine J. Fowers and Frank C. Richardson, Individualism, Family Ideology and Family Therapy, Theory & Psychology, 6, 1(1996): 121-151. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ Sharon Jayson, Hearts divide over marital therapy. USA Today, June 21, 2005. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ R. Varela, et al, "Parenting style of Mexican, Mexican-American, and Caucasian-non-Hispanic families: Social context and cultural influences," Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 4(2004): 657.

- ‚ÜĎ K. Updegraff, "Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American Families: Exploring the Role of Familism," Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 4 (2005).

- ‚ÜĎ Kameguchi, "Family psychology and family therapy in Japan," American Psychologist, 56.1, (2001): 65.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bateson, Gregory. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: University of Chicago Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0226039053.

- Gilbert, Roberta M. Extraordinary Relationships: A New Way of Thinking About Human Interactions. New York: Wiley and Sons, 1992. ISBN 047134690X.

- Hoffman, Lynn. Foundations of Family Therapy: A Conceptual Framework for Systems Change. New York: Basic Books, 1981. ISBN 046502498X.

- Minuchin, Salvador. Families and Family Therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974. ISBN 978-0674292369.

External links

All links retrieved March 23, 2024.

- American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy.

- American Family Therapy Academy.

- Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice in the UK.

- Bowen Center for Study of the Family.

- California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.