Bunsen burner

A Bunsen burner is a common piece of laboratory equipment that produces a single open gas flame. It is generally used for heating, sterilization, and combustion.

History

When the University of Heidelberg hired Robert Bunsen in 1852, the authorities promised to build him a new laboratory building. Heidelberg had just begun to install coal-gas street lighting, so the new laboratory building was also supplied with illuminating gas. Illumination was one thing; a source of heat for chemical operations something quite different. Earlier laboratory lamps left much to be desired regarding economy and simplicity, as well as the quality of the flame; for a burner lamp, it was desirable to maximize the temperature and minimize the luminosity.

Late in 1854, while the building was still under construction, Bunsen suggested certain design principles to the university’s talented mechanic, Peter Desaga, and asked him to construct a prototype. The Bunsen/Desaga design succeeded in generating a hot, sootless, non-luminous flame by mixing the gas with air in a controlled fashion before combustion. Desaga created slits for air at the bottom of the cylindrical burner, the flame igniting at the top.

By the time the building opened early in 1855, Desaga had made 50 such burners for Bunsen's students. Bunsen published a description two years later, and many of his colleagues soon adopted the design.

Description of the setup

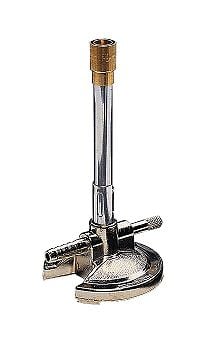

The Bunsen burner in general use today has a weighted base with a connector for a gas line (hose barb) and a vertical tube (barrel) rising from it. The hose barb is connected to a gas nozzle on the lab bench with rubber tubing. Most lab benches are equipped with multiple gas nozzles connected to a central gas source, as well as vacuum, nitrogen, and steam nozzles. The gas then flows up through the base through a small hole at the bottom of the barrel and is directed upward. There are open slots in the side of the tube bottom to admit air into the stream (via the Venturi effect).

Operation

Commonly lit with a match or spark lighter, the burner safely burns a continuous stream of a flammable gas such as natural gas (which is principally methane) or a liquefied petroleum gas such as propane, butane, or a mixture of both. The gas burns at the top of the tube.

The amount of air (or rather oxygen) mixed with the gas stream affects the completeness of the combustion reaction. Less air yields an incomplete and thus cooler reaction, while a gas stream well mixed with air provides oxygen in a roughly equimolar amount, and thus a complete and hotter reaction. The air flow can be controlled by opening or closing the slot openings at the base of the barrel, similar in function to the choke in a car's carburetor.

If the collar at the bottom of the tube is adjusted so more air can mix with the gas before combustion, the flame will burn hotter, appearing blue as a result. If the holes are closed, the gas will only mix with ambient air at the point of combustion, that is, only after it has exited the tube at the top. This reduced mixing produces an incomplete reaction, producing a cooler flame that is brighter yellow, often called a "safety flame" or "luminous flame." The yellow flame is luminous because small soot particles in the flame are heated to incandescence. The yellow flame is considered "dirty" because it leaves a layer of carbon on whatever it is heating. When the burner is regulated to produce a hot, blue flame it can be nearly invisible against some backgrounds.

Increasing the amount of fuel gas flow through the tube by opening the needle valve will of course increase the size of the flame. However, unless the airflow is adjusted as well, the flame temperature will decrease because an increased amount of gas is now mixed with the same amount of air, starving the flame of oxygen. The blue flame in a Bunsen burner is hotter than the yellow flame.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Asimov, Isaac. 1982. Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, 2nd ed. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0385177712.

- Ferguson, Pamela. 2002. World Book's Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, 8th ed. Chicago: World Book. ISBN 0716676001.

- Gillispie, Charles Coulston. 1975. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0684101211.

- Jensen, William B. 2005. The Origin of the Bunsen Burner. J. Chem. Ed. 82 (4): 518.

- Porter, Roy (ed.). 1994. The Biographical Dictionary of Scientists. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0684313200.

- Von Meyer, Ernst. 1906. A History of Chemistry. Tr. George McGowan. New York: The Macmillan Company.

| ||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.