Jones, William (philologist)

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (19 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}} |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Linguists and lexicographers]] |

| − | |||

[[Category:Biography]] | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

| + | {{epname|Jones, William (philologist)}} | ||

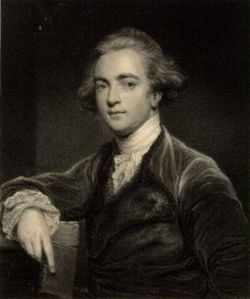

| + | [[Image:Sir William Jones.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Sir William Jones]] | ||

| + | '''William Jones''' (September 28, 1746 – April 27, 1794) was an [[England|English]] [[Philology|philologist]] and student of ancient [[India]]. He is particularly known for his proposition of the existence of a relationship among [[Indo-European languages]]. Having trained and practiced [[law]], Jones combined his love of India with his scholarship, producing significant publications on [[Hindu]] and [[Islam]]ic law. Together with [[Charles Wilkins]], he was instrumental in establishing scholarly interest in Indian [[culture]], which laid the foundation for the field of [[Indology]]. His contributions to [[linguistics]] and inspiring Western interest in the study of India remain significant advances in our understanding of our common heritage as the family of humankind. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ==Life== | ||

| + | |||

| + | William Jones was born on September 28, 1746, in [[London]], [[England]]. His father (also named Sir [[William Jones (mathematician)|William Jones]]) was a famous [[mathematics|mathematician]]. The young William Jones was a [[linguistics|linguistic]] prodigy, learning [[Greek language|Greek]], [[Latin]], [[Persian language|Persian]], [[Arabic language|Arabic]], and the basics of [[Chinese language|Chinese]] at an early age. By the end of his life he knew thirteen languages thoroughly and another twenty-eight reasonably well. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though his father died when he was only three, Jones was still able to attend [[Harrow School]] and go on to [[university]]. Too poor, even with an award, to pay the fees, he gained a job tutoring seven-year-old [[George Spencer, 2nd Earl Spencer|Earl Spencer]], son of [[John Spencer, 1st Earl Spencer|Lord Althorp]], ancestor of [[Diana, Princess of Wales|Princess Diana]]. Jones graduated from the [[University of Oxford]] in 1764. | ||

| + | By the age of 22, Jones was already a well-known [[orientalist]]. He worked as a tutor and translator for the next six years, during which he published, on the request of King [[Christian VII of Denmark]] ''Histoire de Nader Chah'', a French translation of a work originally written in [[Persian language|Persian]]. This would be the first of numerous works on [[Persia]], [[Turkey]], and the [[Middle East]] in general. | ||

| − | + | In 1772, he was made a fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1773, a member of the famous Literary Club of [[Samuel Johnson|Dr. Johnson]]. | |

| + | In the early 1770s, Jones studied [[law]], which would eventually lead him to his life-work in [[India]]. He was called to the bar at the Middle Temple in 1774. After a spell as a circuit judge in [[Wales]], and a fruitless attempt to resolve the issues of the [[American Revolution]] in concert with [[Benjamin Franklin]] in [[Paris]], he was appointed to the Supreme Court of Bengal, India in 1783. He was knighted the same year. | ||

| − | + | In India, he was entranced by its [[culture]], an as-yet untouched field in European scholarship. In 1784, with the help of [[Charles Wilkins]], he founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal and started the journal ''Asiatic Researches''. This was the beginning of the renewal of the interest in India and its culture. | |

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | + | Over the next ten years he would produce a flood of works on India, launching the modern study of the subcontinent in virtually every [[social science]]. He wrote on the local laws, [[music]], [[literature]], [[botany]], and [[geography]], and made the first English translations of several important works of Indian literature. | |

| + | |||

| + | Jones died on April 27, 1794, from an inflammation of [[liver]]. He was only forty-eight years old. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Work== | ||

| − | Jones | + | Of all his discoveries, Jones is best known today for making and propagating the observation that [[Sanskrit]] bore a certain resemblance to classical [[Greek language|Greek]] and [[Latin]]. In ''The Sanscrit Language'' (1786) he suggested that all three languages had a common root, and that indeed they may all be further related, in turn, to [[Gothic language|Gothic]] and the [[Celtic languages|Celtic]] languages, as well as to [[Persian language|Persian]]. |

| − | + | His third discourse (delivered in 1786 and published in 1788) with the famed "philologer" passage is often cited as the beginning of comparative [[linguistics]] and Indo-European studies. This is Jones' most quoted passage, establishing his tremendous find in the history of linguistics: | |

| + | <blockquote>The ''Sanscrit'' language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the ''Greek'', more copious than the ''Latin'', and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists (Jones 1788).</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Jones devised the system of transliteration and managed to translate numerous works into [[English language|English]], among others the ''Laws of Manu'' ''(Manusmriti)'', ''Abhiknana Shakuntala'', ''Ritu Samhara'', and ''Gita Govinda''. | |

| − | + | Jones was also interested in the [[philosophy of law]]. He wrote an ''Essay on the Law of Bailments'', which was influential in both [[England]] and [[United States]], and in 1778 translated the speeches of ''Isaeus on the Athenian right of inheritance''. He also compiled a digest of [[Hindu]] and [[Mahommed]]an law, ''Institutes of Hindu Law, or the Ordinances of Manu'' (1794); ''Mohammedan Law of Succession to Property of Intestates'' (1792), and his ''Mohammedan Law of Inheritance'' (1792) | |

| − | == | + | ==Legacy== |

| − | |||

| − | + | As early as the mid-seventeenth century [[Netherlands|Dutchman]] [[Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn]] (1612-1653) and others had been aware that [[Ancient Persian]] belonged to the same language group as the [[Europe]]an languages, and even though in 1787 [[United States|American]] colonist [[Jonathan Edwards (the younger)|Jonathan Edwards Jr.]] demonstrated that the [[Algonquian languages|Algonquian]] and [[Iroquois|Iroquoian]] language families were related, it was Jones' discovery that caught the imagination of later scholars and became the semi-mythical origin of modern historical comparative [[linguistics]]. He is thus regarded as the first who demonstrated that there was a connection between [[Latin]], [[Greek language|Greek]], and [[Sanskrit]] languages. In addition, Jones was the first westerner who studied [[India]]n classical [[music]], and the first person who attempted to classify Indian [[plant]]s and [[animal]]s. After him, many western universities founded chairs in Sanskrit. | |

| − | + | ==Publications== | |

| − | + | *Jones, William. 1770. ''Histoire de Nader Chah''. Londres. | |

| + | *Jones, William. [1771] 1984. ''Grammar of the Persian Language''. Apt Books. ISBN 0865901384 | ||

| + | *Jones, William. 1786. ''The Sanscrit Language''. | ||

| + | *Jones, William. [1790] 1978. ''Essay on the Law of Bailments''. Garland Publ. ISBN 082403063X | ||

| + | *Jones, William. 1792. ''Mohammedan Law of Inheritance''. Calcutta: J. Cooper. | ||

| + | *Jones, William. 1792. ''Mohammedan Law of Succession to Property of Intestates''. London: Dilly. | ||

| + | *Jones, William. 1794. ''Institutes of Hindu Law, or the Ordinances of Manu''. Calcutta: Government Press. | ||

| + | *Jones, William. [1821] 1970. ''The letters of Sir William Jones''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 019812404X | ||

| + | *Jones, William, C. Wilkins, and Kālidāsa. 1795. ''The story of Dooshwanta and Sakoontalā: Translated from the Mahābhārata, a poem in the Sanskreet language''. London: F. Wingrave. | ||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| − | + | *Campbell, Lyle. 1997. ''American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America''. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195094271 | |

| − | + | *Cannon, Garland H. 1979. ''Sir William Jones: A bibliography of primary and secondary sources''. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 9027209987 | |

| − | * Campbell, Lyle. | + | *Cannon, Garland H. 1991. ''The Life and Mind of Oriental Jones: Sir William Jones, the Father of Modern Linguistics''. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521391490 |

| − | * Cannon, Garland H. | + | *Cannon, Garland H. and Kevin Brine. 1995. ''Objects of enquiry: Life, contributions and influence of Sir William Jones''. New York: NY University Press. ISBN 0814715176 |

| − | * Cannon, Garland H. | + | *Classic Encyclopedia. [http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Sir_William_Jones ''Sir William Jones''] Encyclopedia Britannica 11th edition. Retrieved January 16, 2008. |

| − | * Cannon, Garland H. | + | *Franklin, Michael J. 1995. ''Sir William Jones''. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0708312950 |

| − | * | + | *Mukherjee, S.N. 1968. ''Sir William Jones: A study in eighteenth-century British attitudes to India''. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521057779 |

| − | * | + | *Poser, William J. and Lyle Campbell. 1992. [http://www.billposer.org/Papers/iephm.pdf ''Indo-European practice and historical methodology''] Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 214-236). Retrieved January 16, 2008. |

| − | * Mukherjee, S. N. | ||

| − | * Poser, William J. and Lyle Campbell | ||

| − | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved May 10, 2023. | ||

| + | * [http://www.kamat.com/kalranga/people/pioneers/w-jones.htm Biography of Sir William Jones] – Jones’s biography by Dr. K. L. Kamat. | ||

| − | {{Credit1| | + | {{Credit1|William_Jones_(philologist)|103219960|}} |

Latest revision as of 11:08, 10 May 2023

William Jones (September 28, 1746 – April 27, 1794) was an English philologist and student of ancient India. He is particularly known for his proposition of the existence of a relationship among Indo-European languages. Having trained and practiced law, Jones combined his love of India with his scholarship, producing significant publications on Hindu and Islamic law. Together with Charles Wilkins, he was instrumental in establishing scholarly interest in Indian culture, which laid the foundation for the field of Indology. His contributions to linguistics and inspiring Western interest in the study of India remain significant advances in our understanding of our common heritage as the family of humankind.

Life

William Jones was born on September 28, 1746, in London, England. His father (also named Sir William Jones) was a famous mathematician. The young William Jones was a linguistic prodigy, learning Greek, Latin, Persian, Arabic, and the basics of Chinese at an early age. By the end of his life he knew thirteen languages thoroughly and another twenty-eight reasonably well.

Though his father died when he was only three, Jones was still able to attend Harrow School and go on to university. Too poor, even with an award, to pay the fees, he gained a job tutoring seven-year-old Earl Spencer, son of Lord Althorp, ancestor of Princess Diana. Jones graduated from the University of Oxford in 1764.

By the age of 22, Jones was already a well-known orientalist. He worked as a tutor and translator for the next six years, during which he published, on the request of King Christian VII of Denmark Histoire de Nader Chah, a French translation of a work originally written in Persian. This would be the first of numerous works on Persia, Turkey, and the Middle East in general.

In 1772, he was made a fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1773, a member of the famous Literary Club of Dr. Johnson.

In the early 1770s, Jones studied law, which would eventually lead him to his life-work in India. He was called to the bar at the Middle Temple in 1774. After a spell as a circuit judge in Wales, and a fruitless attempt to resolve the issues of the American Revolution in concert with Benjamin Franklin in Paris, he was appointed to the Supreme Court of Bengal, India in 1783. He was knighted the same year.

In India, he was entranced by its culture, an as-yet untouched field in European scholarship. In 1784, with the help of Charles Wilkins, he founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal and started the journal Asiatic Researches. This was the beginning of the renewal of the interest in India and its culture.

Over the next ten years he would produce a flood of works on India, launching the modern study of the subcontinent in virtually every social science. He wrote on the local laws, music, literature, botany, and geography, and made the first English translations of several important works of Indian literature.

Jones died on April 27, 1794, from an inflammation of liver. He was only forty-eight years old.

Work

Of all his discoveries, Jones is best known today for making and propagating the observation that Sanskrit bore a certain resemblance to classical Greek and Latin. In The Sanscrit Language (1786) he suggested that all three languages had a common root, and that indeed they may all be further related, in turn, to Gothic and the Celtic languages, as well as to Persian.

His third discourse (delivered in 1786 and published in 1788) with the famed "philologer" passage is often cited as the beginning of comparative linguistics and Indo-European studies. This is Jones' most quoted passage, establishing his tremendous find in the history of linguistics:

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists (Jones 1788).

Jones devised the system of transliteration and managed to translate numerous works into English, among others the Laws of Manu (Manusmriti), Abhiknana Shakuntala, Ritu Samhara, and Gita Govinda.

Jones was also interested in the philosophy of law. He wrote an Essay on the Law of Bailments, which was influential in both England and United States, and in 1778 translated the speeches of Isaeus on the Athenian right of inheritance. He also compiled a digest of Hindu and Mahommedan law, Institutes of Hindu Law, or the Ordinances of Manu (1794); Mohammedan Law of Succession to Property of Intestates (1792), and his Mohammedan Law of Inheritance (1792)

Legacy

As early as the mid-seventeenth century Dutchman Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn (1612-1653) and others had been aware that Ancient Persian belonged to the same language group as the European languages, and even though in 1787 American colonist Jonathan Edwards Jr. demonstrated that the Algonquian and Iroquoian language families were related, it was Jones' discovery that caught the imagination of later scholars and became the semi-mythical origin of modern historical comparative linguistics. He is thus regarded as the first who demonstrated that there was a connection between Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit languages. In addition, Jones was the first westerner who studied Indian classical music, and the first person who attempted to classify Indian plants and animals. After him, many western universities founded chairs in Sanskrit.

Publications

- Jones, William. 1770. Histoire de Nader Chah. Londres.

- Jones, William. [1771] 1984. Grammar of the Persian Language. Apt Books. ISBN 0865901384

- Jones, William. 1786. The Sanscrit Language.

- Jones, William. [1790] 1978. Essay on the Law of Bailments. Garland Publ. ISBN 082403063X

- Jones, William. 1792. Mohammedan Law of Inheritance. Calcutta: J. Cooper.

- Jones, William. 1792. Mohammedan Law of Succession to Property of Intestates. London: Dilly.

- Jones, William. 1794. Institutes of Hindu Law, or the Ordinances of Manu. Calcutta: Government Press.

- Jones, William. [1821] 1970. The letters of Sir William Jones. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 019812404X

- Jones, William, C. Wilkins, and Kālidāsa. 1795. The story of Dooshwanta and Sakoontalā: Translated from the Mahābhārata, a poem in the Sanskreet language. London: F. Wingrave.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Campbell, Lyle. 1997. American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195094271

- Cannon, Garland H. 1979. Sir William Jones: A bibliography of primary and secondary sources. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 9027209987

- Cannon, Garland H. 1991. The Life and Mind of Oriental Jones: Sir William Jones, the Father of Modern Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521391490

- Cannon, Garland H. and Kevin Brine. 1995. Objects of enquiry: Life, contributions and influence of Sir William Jones. New York: NY University Press. ISBN 0814715176

- Classic Encyclopedia. Sir William Jones Encyclopedia Britannica 11th edition. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Franklin, Michael J. 1995. Sir William Jones. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0708312950

- Mukherjee, S.N. 1968. Sir William Jones: A study in eighteenth-century British attitudes to India. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521057779

- Poser, William J. and Lyle Campbell. 1992. Indo-European practice and historical methodology Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 214-236). Retrieved January 16, 2008.

External links

All links retrieved May 10, 2023.

- Biography of Sir William Jones – Jones’s biography by Dr. K. L. Kamat.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.