Difference between revisions of "Wang Xizhi" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Robot: Remove claimed tag) |

Andy Wilhelm (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}} | + | {{ce}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}} |

{| cellpadding=3px cellspacing=0px bgcolor=#f7f8ff style="float:right; border:1px solid; margin:5px" | {| cellpadding=3px cellspacing=0px bgcolor=#f7f8ff style="float:right; border:1px solid; margin:5px" | ||

!style="background:#ccf; border-bottom:1px solid" colspan=2|[[Chinese name|Names]] | !style="background:#ccf; border-bottom:1px solid" colspan=2|[[Chinese name|Names]] | ||

Revision as of 04:12, 7 April 2008

| Names | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chinese: | 王羲之 |

| Pinyin: | Wáng Xīzhī |

| Wade-Giles: | Wang Hsi-chih |

| Zi: | Yìshào (逸少) |

| Hao: | Dànzhāi (澹斋) |

| Also known as: | Shūshèng (書聖, literally Sage of Calligraphy) |

- This is a Chinese name; the family name is 王 (Wang).

Wang Xizhi (Wang Hsi-chih, 王羲之, 303–361) was the most celebrated Chinese calligrapher, traditionally referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖). Wang Xizhi (Wang Hsi-chih) lived in the fourth century, during the Eastern Jin period, when a growing appreciation for expressive writing styles led to the first collecting and cataloging of the works of individual calligraphers. Wang Xizhi was equally skilled in cao shu (regular style); hsing shu (xing shu, running style), which features connections between individual characters and slightly abbreviated forms; and ts’ao shu (kai shu, grass style), which appears as though the wind had blown over the grass in a manner at the same disorderly and orderly. He produced a large number of works of calligraphy, but within 1700 years, all of his original works had been lost or destroyed in wars. Some of them, however, were preserved as copies, tracings, stone inscriptions and rubbings.

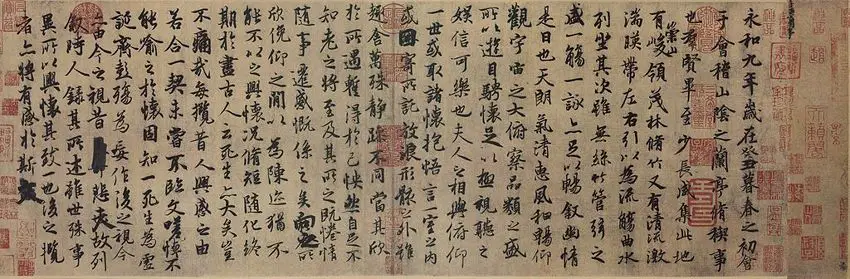

Wang Xizhi’s most famous work is Lantingji Xu (Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion), composed in year 353. Written in semi-cursive script, it is the most well-known and most-copied piece of Chinese calligraphy. It describes a gathering of forty-two literati including Xie An and Sun Chuo (孙绰) at the Orchid Pavilion at Lanting near the town Shaoxing, Zhejiang during the Spring Purification Festival (Xiuxi), to compose poems and enjoy wine. The preface consists of 324 Chinese characters in 28 lines. It is also a celebrated work of literature, flowing rhythmically and giving rise to several Chinese idioms.

Background : Chinese Calligraphy

In China, Korea, and Japan, calligraphy is a pure art form. Chinese calligraphy is derived from the written form of the Chinese language, which is not alphabetical but is composed of characters, pictorial images representing words or sounds. Each character is written as a series of brush strokes within an invisible square. A great calligrapher is one who captures not only the correct position of the lines, but also the essence of each character’s meaning with his brush strokes.

Wang Xizhi (Wang Hsi-chih) and his son Wang Xianzhi (Wang Hsien-chih) who lived in the fourth century, are traditionally considered to be the greatest exponents of Chinese calligraphy. Few of their original works have survived, but a number of their writings were engraved on stone tablets, and rubbings were made from them. Many great calligraphers imitated their styles, but none ever surpassed them.

Wang Xizhi (Wang Hsi-chih) not only provided the greatest example of the regular style of writing, but created a new style by relaxing the arrangement of the strokes somewhat and allowing the brush to trail easily from one word to another. This is called hsing shu, or “running style,” as though the hand were walking fast while writing. This style led to the creation of ts'ao shu, or “grass style,” named for its appearance, as though the wind had blown over the grass in a manner at the same disorderly and orderly. Chinese words in “grass style” are greatly simplified forms of the regular style, and can be deciphered only by those who have practiced calligraphy for years. Grass style is used by the calligrapher who wishes to produce a work of abstract art.

Chinese calligraphy requires only ink, an ink stone, a good brush, and good paper (or silk), the “four treasures” found in a Chinese scholar’s study. A skilled calligrapher moves quickly and confidently, in a flowing motion, giving interesting shapes to his strokes and composing beautiful structures without any retouching, while maintaining well-balanced spaces between the strokes. Calligraphy requires years of practice and training.

The fundamental inspiration for Chinese calligraphy is nature. In regular style, each stroke suggests the form of a natural object. Every stroke of a piece of fine calligraphy has energy and life, poise and movement, and a force which interacts with the movement of other strokes to form a well-balanced whole.

Wang Xizhi (Wang Hsi-chih ) was a Daoist, and one of his most renowned works was a transcription of the Book of the Yellow Court. Daoists considered calligraphy as essential in the making of inscriptions and talismans; their efficacy was believed to depend on the precision of the strokes from which they were created.

Life

Wang Xizhi was born in 303 C.E. in Linyi, Shandong (臨沂; 山東), and spent most of his life in the present-day Shaoxing, Zhejiang( 紹興; 浙江). He learned the art of calligraphy from Wei Shuo ( 衛鑠; 272–349), courtesy name Mouyi (茂猗), sobriquet He'nan (和南)), commonly addressed just as Lady Wei (衛夫人), a calligrapher of Eastern Jin, who established consequential rules about the regular script. He excelled in every script but particularly in the semi-cursive script (行書; pinyin: Xíngshū, Japanese: 行書 (gyōsho), Korean: 행서(haengseo)), a partially cursive style of Chinese calligraphy. Unfortunately, none of his original works remains today.

According to tradition, even during Wang Xizhi (Wang Hsi-chih)'s lifetime, just a few of his written characters or his signature were considered priceless. Through the ages, Chinese calligraphers have copied preserved examples of his style. Wang Xizhi (Wang Hsi-chih)'s memorial, written in hsing shu, or “running script,” has become the model for that particular style. The writing of the memorial itself became a historical incident and a popular subject for paintings, especially during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) when interest in ancient arts was revived.

Wang Xizhi had seven children, all of whom were notable calligraphers. Among other generations of calligraphers in the family, Wang Xianzhi (Wang Hsien-chih , 344–386 C.E.), the youngest son of Wang Xizhi (Wang Hsi-chih), was the most famous.

Wang Xizhi is particularly remembered for his hobby rearing geese. According to legend, he learned the secret of how to turn his wrist while writing by observing how the geese move their necks.

Wang Xizhi was equally skilled in cao shu (regular style), hsing shu (xing shu, running style) and ts’ao shu (grass style). He produced a large number of works of calligraphy, but within 1700 years, all of his original works had been lost or destroyed in wars. Some hand copies of his calligraphy works include Lan Tin Xu, Sheng Jiao Xu, Shi Qi Tie, and Sang Luan Tie.

Lantingji Xu (“Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion”)

Wang Xizhi’s most famous work is Lantingji Xu (Traditional Chinese: 蘭亭集序; Simplified Chinese: 兰亭集序; pinyin: Lántíngjí Xù; Wade-Giles: Lant'ingchi Hsü; literally "Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion") or Lanting Xu (蘭亭序), composed in year 353. Written in semi-cursive script, it is the most well-known and most-copied piece of Chinese calligraphy. It describes a gathering of forty-two literati including Xie An and Sun Chuo (孙绰) at the Orchid Pavilion at Lanting near the town Shaoxing, Zhejiang during the Spring Purification Festival (Xiuxi), to compose poems and enjoy wine. The gentlemen had engaged in a drinking contest: wine cups were floated down a small winding creek as the men sat along its banks; whenever a cup stopped, the man closest to the cup was required to empty it and write a poem. In the end, twenty-six of the participants composed thirty-seven poems.[1]

The preface consists of 324 Chinese characters in 28 lines. The character zhi (之) appears 17 times, but no two look the same. It is also a celebrated work of literature, flowing rhythmically and giving rise to several Chinese idioms. It is a piece of improvisation, as can be seen from the revisions in the text.

Emperor Taizong of Tang liked Wang's calligraphy so much that he ordered a search for the original copy of Lanting Xu. According to legend, the original copy was passed down to successive generations in the Wang family in secrecy until the monk Zhiyong, dying without an heir, left it to the care of a disciple monk, Biancai. Tang Taizong sent emissaries on three occasions to retrieve the text, but each time, Biancai responded that it had been lost. Unsatisfied, the emperor dispatched censor Xiao Yi who, disguised as a wandering scholar, gradually gained of confidence of Biancai and persuaded him to bring out the "Orchid Pavilion Preface." Thereupon, Xiao Yi seized the work, revealed his identity, and rode back to the capital. The overjoyed emperor had it traced, copied, and engraved into stone for posterity. Taizong treasured the work so much that he had the original interred in his tomb after his death.[2] The story of Tang Taizong seizing the Lantingji xu has since the subject of numerous plays and novels.

The original is lost, but there are a number of fine tracing copies and rubbings.

| Original | Pinyin | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 蘭 亭 集 序 | lán tíng jí xù | Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion |

| (王羲之) | wáng xī zhī | (by Wang Xizhi) |

| 永和九年, | yǒnghé jiǔ nián | In the Template:Comment, |

| 歲在癸丑, | suì zài guǐ chǒu | Which was the year of the Yin Water Ox, |

| 暮春之初, | mùchūn zhī chū | At the Template:Comment, |

| 會于會稽山陰之蘭亭, | huì yú Guìjī Shānyīn zhī lán tíng | We all gathered at the orchid pavilion in Shanyin County, Guiji Prefecture (modern day Shaoxing), |

| 脩禊事也。 | xiūxì shì yě | For the Spring Purification Festival. |

| 群賢畢至, | qún xián bì zhì | All of the prominent people were there, |

| 少長咸集。 | shào zhǎng xián jí | From old to young. |

| 此地有崇山峻領, | cǐdì yǒu chóngshānjùnlǐng | This was an area of high mountains and lofty peaks, |

| 茂林修竹, | màolínxiūzhú | With an exuberant growth of trees and bamboos, |

| 又有清流激湍, | yòu yǒu qīngliú jī tuān | Which also had clear rushing water, |

| 映帶左右。 | yìng dài zuǒyòu | Which reflected the sunlight as it flowed past either side of the pavilion. |

| 引以為流觴曲水,列坐其次; | yǐn yǐ wéi liú shāng qū shuǐ, liè zuò qícì | The pavilion divided the flowing water into two winding brooks, and all the guests were sitting side by side; |

| 雖無絲竹管弦之盛, | suī wú sīzhú guǎnxián zhī shèng | Although we lacked the boisterousness of a live orchestra, |

| 一觴一詠,亦足以暢敘幽情。 | yī shāng yī yǒng, yì zúyǐ chàngxù yōuqíng | With a cup of wine here and a reciting of poetry there, it was sufficient to allow for a pleasant exchange of cordial conversations. |

| 是日也,天朗氣清, | shì rì yě, tiān lǎng qì qīng | On this particular day, the sky was bright and the air was clear, |

| 惠風和暢,仰觀宇宙之大, | huìfēnghéchàng, yǎng guān yǔzhòu zhī dà | With a gentle breeze which was blowing freely. When looking up, one could see the vastness of the heavens, |

| 俯察品類之盛,所以遊目騁懷, | fǔ chá pǐn lèi zhī shèng, suǒyǐ yóu mù chěnghuái | And when looking down, one could observe the abundance of things. The contentment of allowing one’s eyes to wander, |

| 足以極視聽之娛,信可樂也。 | zúyǐ jí shìtīng zhī yú, xìn kě lè yě | Was enough to reach the heights of delight for the sight and sound. What joy. |

| 夫人之相與俯仰一世, | fú rén zhī xiāngyǔ fǔyǎng yī shì | Now all people live in this world together, |

| 或取諸懷抱,晤言一室之內; | huò qǔ zhū huáibào, wù yán yī shì zhī nèi | Some will take all of their aspirations, and share them in private with a friend; |

| 或因寄所托,放浪形骸之外。 | huò yīn jì suǒ tuō, fànglàngxínghái zhī wài | Still others will abandon themselves to reckless pursuits. |

| 雖趣舍萬殊,靜躁不同, | suī qǔshě wàn shū, jìng zào bùtóng | Even though everyone makes different choices in life, some thoughtful and some rash, |

| 當其欣于所遇,暫得于己, | dāng qí xīn yú suǒ yù, zàn dé yú jǐ | When a person meets with joy, he will temporarily be pleased, |

| 快然自足,不知老之將至。 | kuài rán zìzú, bùzhī lǎo zhī jiāng zhì | And will feel content, but he is not mindful that old age will soon overtake him. |

| 及其所之既倦,情隨事遷, | jí qí suǒ zhī jì juàn, qíng suí shì qiān | Wait until that person becomes weary, or has a change of heart about something, |

| 感慨係之矣。 | gǎnkǎi xì zhī yǐ | And will thus be filled with regrets. |

| 向之所欣,俛仰之間, | xiàng zhī suǒ xīn, fǔyǎng zhī jiān | The happiness of the past, in the blink of eye, |

| 已為陳迹,猶不能不以之興懷; | yǐ wéi chén jī, yóu bùnéngbù yǐ zhī xìng huái | Will have already become a distant memory, and this cannot but cause one to sigh; |

| 况修短隨化,終期于盡。 | kuàng xiū duǎn suí huà, zhōng qí yú jìn | In any case, the length of a man’s life is determined by the Creator, and we will all turn to dust in the end. |

| 古人云﹕「死生亦大矣。」 | gǔ rén yún: sǐ shēng yì dà yǐ | The ancients have said, “Birth and Death are both momentous occasions.” |

| 豈不痛哉! | qǐbù tòng zāi | Isn’t that sad! |

| 每攬昔人興感之由, | měi lǎn xí rén xìng gǎn zhī yóu | Every time I consider the reasons for why the people of old had regrets, |

| 若合一契,未嘗不臨文嗟悼, | ruò hé yī qì, wèicháng bù lín wén jiē dào | I am always moved to sadness by their writings, |

| 不能喻之于懷。 | bùnéng yù zhī yú huái | And I can not explain why I am saddened. |

| 固知一死生為虛誕, | gù zhī yī sǐ shēng wéi xūdàn | I most certainly know that it is false and absurd to treat life and death as one and the same, |

| 齊彭殤為妄作。 | qí péng shāng wéi wàngzuò | And it is equally absurd to think of dying at an old age as being the same as dying at a young age. |

| 後之視今,亦由今之視昔。 | hòu zhī shì jīn, yì yóu jīn zhī shì xí | When future generations look back to my time, it will probably be similar to how I now think of the past. |

| 悲夫!故列敘時人, | bēi fú! gù liè xù shí rén | What a shame! Therefore, when I list out the people that were here, |

| 錄其所述,雖世殊事異, | lù qí suǒ shù, suī shì shū shì yì | And record their musings, even though times and circumstances will change, |

| 所以興懷,其致一也。 | suǒ yǐ xìng huái, qí zhì yī yě | As for the things that we regret, they are the same. |

| 後之攬者,亦將有感于斯文。 | hòu zhī lǎn zhě, yì jiāng yǒu gǎn yú sī wén | For the people who read this in future generations, perhaps you will likewise be moved by my words. |

Anecdote

In 648, Tang Taizong wrote an article about Xuan Zang's journey to the west, and wanted to carve the article onto stone. He loved Wang Xizhi's calligraphy, but Wang Xizhi had died hundreds of years ago. So he ordered Huai Ren to collect characters from Wang Xizhi's existing works of calligraphy. It took Huai Ren twenty-five years to collect all characters and put them together, since many of them were not the same size, to finish this project.. Since Huai Ren was a master calligrapher himself, the finished work, Sheng Jiao Xu, looks just like Wang Xizhi's original work. [3]

Notes

- ↑ Richard Kurt Kraus, Brushes with Power (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 27.

- ↑ Lothar Ledderose, Mi Fu and the Classical Tradition of Chinese Calligraphy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979), 18.

- ↑ Chinese calligraphy master Wang Xizhi, Lixin Wang. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

| This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

- Bischoff, Friedrich Alexander. 1985. The songs of the Orchis Tower. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 344702500X ISBN 9783447025003

- Chiang, Yee. 1973. Chinese calligraphy; an introduction to its aesthetic and technique. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674122259 ISBN 9780674122253

- Hook, Brian, and Denis Crispin Twitchett. 1991. The Cambridge encyclopedia of China. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052135594X ISBN 9780521355940

- Nakata, Yūjirō, and Jeffrey Hunter. 1983. Chinese calligraphy. A History of the art of China. New York: Weatherhill/Tankosha. ISBN 0834815265 ISBN 9780834815261

- Perkins, Dorothy. 1999. Encyclopedia of China the essential reference to China, its history and culture. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0816026939 ISBN 9780816026937

- Li, Siyong, "Wang Xizhi". Encyclopedia of China (Chinese Literature Edition), 1st ed. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

External links

- Wang XiZhi's calligraphy. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- Lantingji Xu. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- Chinese Calligraphy. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- Wang Xizhi. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.