Difference between revisions of "Toda people" - New World Encyclopedia

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) (images shifted) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (25 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ready}} | + | {{approved}}{{submitted}}{{ready}}{{images OK}}{{copyedited}} |

| + | |||

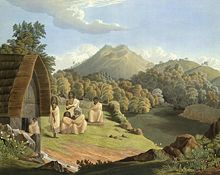

[[Image:Kandelmund toda 1837.jpg|thumb|right|220px|The Toda mund, from, Richard Barron, 1837, "View in India, chiefly among the Neelgherry Hills'. Oil on canvas.]] | [[Image:Kandelmund toda 1837.jpg|thumb|right|220px|The Toda mund, from, Richard Barron, 1837, "View in India, chiefly among the Neelgherry Hills'. Oil on canvas.]] | ||

| − | The '''Toda people''' designates a small [[pastoral]] community | + | |

| + | The '''Toda people''' designates a small [[pastoral]] community that live on the isolated [[Nilgiris district|Nilgiri plateau]] of Southern [[India]]. Prior to the late eighteenth century, the Toda coexisted locally with other communities, including the [[Badaga]], [[Kota]], and [[Kurumba]], in a loose [[caste]]-like community organization. The Toda held the top ranking among those communities. The Toda population has hovered in the range 700 to 900 during the last century. Although an insignificant fraction of the large population of India, the Toda have attracted (since the late eighteenth century), "a most disproportionate amount of attention because of their ethnological aberrancy" and "their unlikeness to their neighbours in appearance, manners, and customs."<ref name=emeneau1984>{{Harv|Emeneau|1984|pp=1-2}}</ref> The study of their culture by anthropologists and linguists would prove important in the creation of the fields of [[social anthropology]] and [[ethnomusicology]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The revered place of the [[buffalo]] in Toda society represents a remarkable feature of their life. Over the centuries, the Toda came to rely heavily upon the buffalo for their livelihood. They created religious and social values around the buffalo, including their [[origin myth]]. The first [[sacred buffalo]] had been created by the [[gods]] before the first Toda man and woman. [[Kona Shastra]], the annual sacrifice of a male buffalo constitutes their central religious ceremony. The person who tends the holy sacred buffalo, the divine milkman, has the highest position in Toda society. The Toda way of life has been threatened by contact with modern India, a shift from [[herding]] to [[agriculture]], and a loss of grazing land as a result of the government of [[Tamil Nadu]] conducting a reforestation program. [[UNESCO]] has declared the Toda peoples home land, [[Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve]], and [[International Biosphere Reserve]] a [[World Heritage Site]]. The initiatives by UNESCO may help the Toda people preserve their traditional way of life. Yet, the conveniences of modern life, such has more comfortable housing and clothing, as well as the benefits of the [[Information Age]], may hasten the demise of the Toda people's traditional religious beliefs and social practices. | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| − | The Toda traditionally live in settlements consisting of three to seven small thatched houses, constructed in the shape of half-barrels and spread across the slopes of the pasture.<ref name=britannica-toda>Encyclopædia Britannica | + | The Toda traditionally live in settlements consisting of three to seven small thatched houses, constructed in the shape of half-barrels and spread across the slopes of the pasture.<ref name=britannica-toda>Encyclopædia Britannica, Toda.</ref> They traditionally trade [[dairy product]]s with their Nilgiri neighbors.<ref name=britannica-toda/> Toda religion centers on the [[buffalo]]; consequently, they perform rituals for all dairy activities as well as for the ordination of dairymen-priests. The religious and [[funerary rites]] provide the social context in which the Toda compose and chant complex poetic songs about the cult of the buffalo.<ref name=britannica-toda/> Fraternal [[polyandry]], fairly common in traditional Toda society, has now largely been abandoned. |

| − | During the last quarter of the twentieth century, agriculture by people moving into the area depleted some Toda pasture land.<ref name=britannica-toda/> Afforestation by the State Government of [[Tamil Nadu]] has also taken a toll on their grazing land. That has threatened to undermine Toda culture by greatly diminishing the buffalo herds. During the last decade, both Toda society and culture have also become the focus of an international effort at culturally sensitive environmental restoration. <ref>{{Harvnb|Chhabra|2006}}.</ref> | + | During the last quarter of the twentieth century, agriculture by people moving into the area depleted some Toda pasture land.<ref name=britannica-toda/> Afforestation by the State Government of [[Tamil Nadu]] has also taken a toll on their grazing land. That has threatened to undermine Toda culture by greatly diminishing the buffalo herds. During the last decade, both Toda society and culture have also become the focus of an international effort at culturally sensitive environmental restoration.<ref>{{Harvnb|Chhabra|2006}}.</ref> The Toda lands now belong to the [[Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve]], a [[UNESCO]]-designated [[International Biosphere Reserve]]. UNESCO has the area under consideration for selection as a [[World Heritage Site]].<ref name="UNESCO">UNESCO, [http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/2103/ World Heritage sites, Tentative lists, April 2007.] Retrieved July 8, 2008.</ref> |

==Population== | ==Population== | ||

| − | |||

| − | According to M. B. Emeneau, the successive decennial [[Census of India]] figures for the Toda are: 1871 (693), 1881 (675), 1891 (739), 1901 (807), 1911 (676) (corrected from 748), 1951 (879), 1961 (759), 1971 (812). These in his judgment:<blockquote> | + | According to M.B. Emeneau, the successive decennial [[Census of India]] figures for the Toda are: 1871 (693), 1881 (675), 1891 (739), 1901 (807), 1911 (676) (corrected from 748), 1951 (879), 1961 (759), 1971 (812). These in his judgment:<blockquote>Justifies concluding that a figure between 700 and 800 is likely to be near the norm, and that variation in either direction is due on the one hand to epidemic disaster and slow recovery thereafter (1921 (640), 1931 (597), 1941 (630)) or on the other hand to an excess of double enumeration (suggested already by census officers for 1901 and 1911, and possibly for 1951). Another factor in the uncertainty in the figures is the declared or undeclared inclusion or exclusion of Christian Todas by the various enumerators … Giving a figure between 700 and 800 is highly impressionistic, and may for the immediate present and future be pessimistic, since [[public health]] efforts applied to the community seem to be resulting in an increased [[birth rate]] and consequently, one would expect, in an increased population figure. However, earlier predictions that the community was declining were overly pessimistic and probably never well-founded.<ref name=emeneau1984/> |

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | + | The origin of the Todas remains unclear. One of the original tribes, they have been inhabiting the highest regions of [[the Nilgiris]] mountain range and have remained secluded for a very long time. Around 1823, the Collector of [[Coimbatore]], [[John Sullivan]], took a fancy to their land and bought it from them for a mere one rupee. He established a town at the place named [[Ootacamund|Udagamandalam]] on the land. The interaction with [[western civilization]] caused many changes in the lifestyle of the Todas. | |

| − | The origin of the Todas | ||

| − | |||

| − | Around 1823, the Collector of [[Coimbatore]], John Sullivan, took a fancy to their land and bought it from them for a mere one rupee. He established a town at the place named [[Ootacamund|Udagamandalam]] on | ||

| − | |||

==Culture and society== | ==Culture and society== | ||

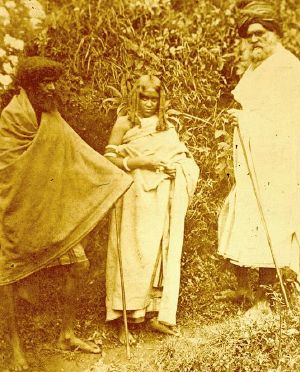

[[Image:Toda men women 1871.jpg|thumb|right|Photograph of two Toda men and a woman. Nilgiri Hills, 1871.]] | [[Image:Toda men women 1871.jpg|thumb|right|Photograph of two Toda men and a woman. Nilgiri Hills, 1871.]] | ||

| − | The Toda dress consists of a single piece of cloth, | + | The Toda dress consists of a single piece of cloth, worn like the plaid of a Scottish highlander. Cattle-herding and dairy-work constitute their sole occupation. They once practiced [[fraternal polyandry]], a practice in which a woman marries all the brothers of a family, but no longer do so.<ref name="truth">{{Harv|Walker|2004}}.</ref> The ratio of females to males stands at about three to five. The [[Kota tribe|Kota]] represent the most closely related people to the Toda, both ethnically and linguistically. |

| + | |||

| + | The Todas worship their dairy-buffaloes, but they have a whole pantheon of other gods. Kona Shastra, the annual sacrifice of a male buffalo calf, constitutes their only purely religious ceremony. Toda villages, called ''munds,'' usually consist of five buildings or huts, of which they use three as dwellings, one as a dairy and the other as a shelter for the calves at night. The inhabitants of a ''mund,'' generally related, consider themselves one family. The Todas numbered 807 in 1901, and their current population stands at around 1,100.<ref>W.H.R. Rivers, ''The Todas'' (1906).</ref> | ||

==Religion== | ==Religion== | ||

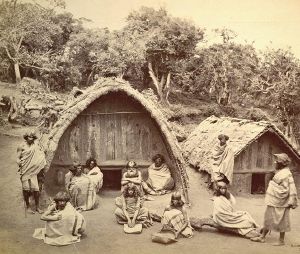

| − | [[Image:Bourne toda mund1869.jpg| | + | [[Image:Bourne toda mund1869.jpg|right|thumb|A Toda mund, 1869, Samuel Bourne]] |

<!--[[Image:TodaTemple1.jpg|thumb|A Toda temple in Muthunadu Mund near Ooty, India.]]—> | <!--[[Image:TodaTemple1.jpg|thumb|A Toda temple in Muthunadu Mund near Ooty, India.]]—> | ||

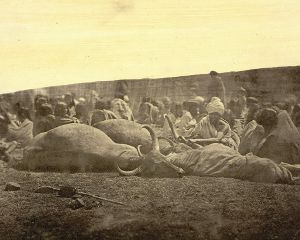

| − | [[Image:Toda green funeral1871.jpg|thumb|Photograph (1871-72) of a Toda green funeral.]] | + | [[Image:Toda green funeral1871.jpg|thumb|right|Photograph (1871-72) of a Toda green funeral.]] |

| − | According to the Todas, the goddess Teikirshy and her brother first created the sacred buffalo and then the first Toda man. | + | According to the Todas, the goddess Teikirshy and her brother first created the sacred buffalo and then the first Toda man. They created the first Toda woman from the right rib of the first Toda man. The Toda religion also forbids them from walking across bridges, rivers must be crossed on foot, or swimming. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Toda temples | + | The Todas especially revere the [[Pandava]]s, although little evidence exists that the believe in the rest of the [[Hindu mythology]]. Toda temples, constructed in a circular pit lined with stones, look quite similar in appearance and construction to Toda huts. |

| − | From Frazer's ''[[Golden Bough]]'' | + | From Frazer's ''[[Golden Bough]],'' 1922: |

| − | + | <blockquote>Among the Todas of Southern India the holy milkman, who acts as priest of the sacred dairy, is subject to a variety of irksome and burdensome restrictions during the whole time of his incumbency, which may last many years. Thus he must live at the sacred dairy and may never visit his home or any ordinary village. He must be celibate; if he is married he must leave his wife. On no account may any ordinary person touch the holy milkman or the holy dairy; such a touch would so defile his holiness that he would forfeit his office. It is only on two days a week, namely Mondays and Thursdays, that a mere layman may even approach the milkman; on other days if he has any business with him, he must stand at a distance (some say a quarter of a mile) and shout his message across the intervening space. Further, the holy milkman never cuts his hair or pares his nails so long as he holds office; he never crosses a river by a bridge, but wades through a ford and only certain fords; if a death occurs in his clan, he may not attend any of the funeral ceremonies, unless he first resigns his office and descends from the exalted rank of milkman to that of a mere common mortal. Indeed it appears that in old days he had to resign the seals, or rather the pails, of office whenever any member of his clan departed this life. However, these heavy restraints are laid in their entirety only on milkmen of the very highest class</blockquote> | |

==Language== | ==Language== | ||

| − | The [[Toda language]] | + | The [[Toda language]] belongs to the [[Dravidian languages|Dravidian]] family. |

| − | Like their ethnology, | + | Like their ethnology, they have aberrant language and difficult phonologically. Toda (along with their neighbors, the Kota) belongs to the the southern subgroup of the historical family proto-South-Dravidian, splitting off from South Dravidian after Kannada and Telegu, but before Malayam. In modern linguistic terms, the aberrancy of Toda results from disproportionately numerous rules, both early and recent in their ordering, not shared by the other South Dravidian languages (and shared only to a small extent by Kota).<ref name=emeneau1984/> |

==Toda dwellings and lifestyle== | ==Toda dwellings and lifestyle== | ||

| − | [[Image:Toda Hut.JPG|thumb|right|The hut of a Toda Tribe of Nilgiris, India | + | [[Image:Toda Hut.JPG|thumb|right|The hut of a Toda Tribe of Nilgiris, India.]] |

| − | The Todas live in small hamlets called ''munds''. The Toda huts, of an oval, pent-shaped construction, | + | The Todas live in small hamlets called ''munds''. The Toda huts, of an oval, pent-shaped construction, usually stand ten feet (3 m) high, eighteen feet (5.5 m) long and nine feet (2.7 m) wide. Built of bamboo fastened with rattan and thatched, a wall of loose stones encloses each hut. Dressed stones (mostly [[granite]]) usually make up the front and back of the hut. Each hut has only a tiny entrance at the front—about 3 feet (90 cm) wide, 3 feet (90 cm) tall. That unusually small entrance serves as a means of protection from wild animals. The Toda art forms, a kind of rock mural painting, decorates the front portion of the hut. Thicker bamboo canes arch to give the hut its basic tent shape. Tied close and parallel to each other, thinner bamboo canes lay over that frame. Dried grass stacks were laid over thatas thatch. |

| − | The forced interaction with | + | The forced interaction with civilization has caused a lot of changes in the lifestyle of the Todas. The Todas used to be a pastoral people but now increasingly venture into agriculture and other occupations. They used to be strict vegetarians but some can be now be seen eating non-vegetarian food. Although many Toda have abandoned their traditional distinctive huts for concrete houses,<ref name="truth"/> a movement has gained momentum to build tradition barrel-vaulted huts. During the last decade, forty new huts have been built and many Toda sacred dairies have been renovated.<ref>{{Harv|Chhabra|2005}} Quote: "… over the past ten years, we have approached government and private agencies for sponsoring traditional houses. Today, we have been able to assist in funding over forty barrel-vaulted houses. Added to these are the scores of existing temples—two are conical and the rest barrel-vaulted."</ref> |

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| + | * [[Nilgiris district]]<br/> | ||

| + | * [[Karnataka]]<br/> | ||

| + | * [[Polyandry]]<br/> | ||

| + | * [[Indian vernacular architecture]]<br/> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | * Chhabra, Tarun. "How Traditional Ecological Knowledge addresses Global Climate change: The perspective of the Todas—the indigenous people of the Nilgiri hills of South India." ''Proceedings of the Earth in Transition: First World Conference'' (2005) | ||

| + | * Chhabra, Tarun. "Restoring the Toda Landscapes of the Nilgiri Hills in South India. " ''Plant Talk'' 44 (2006) | ||

| + | * Emeneau, M.B. "Oral Poets of South India: Todas." ''Journal of American Folklore'' 71 (281) (1958): 312-324. | ||

| + | * Emeneau, M.B. ''Toda Songs.'' Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971. ISBN 0198151292. | ||

| + | * Emeneau, Murray Barnson. "Ritual Structure and Language Structure of the Todas." ''Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, N.S.,'' 64: 6. 1974. ISBN 0871696460. | ||

| + | * Emeneau, Murray Barnson. "Toda grammar and texts." ''Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society,'' 155. Philadelphia: Soc, 1984. ISBN 0871691558. | ||

| + | * Emeneau, M. B. "A Century of Toda Studies: Review of ''The Toda of South India: A New Look'' by Anthony R. Walker; M. N. Srinivas." ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'' 108(4) (1988): 605-609. | ||

| + | * Rivers, W.H.R. ''The Todas.'' London: Macmillan, 1906. OCLC 3359858. | ||

| + | * Rivers, William H.R. "[http://orion.oac.uci.edu/~dbell/Toda.pdf The Todas ''Anthropological Publications'' (1909).] Retrieved July 16, 2008. | ||

| + | * Walker, Anthony R. "The Truth About the Toda." ''Frontline, The Hindu'' (2004) | ||

| + | * Walker, Anthony R. ''Between Tradition and Modernity and Other Essays on the Toda of South India''. Delhi: B.R. Pub. Corp, 1998. ISBN 8170189160. | ||

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| − | + | All links retrieved April 30, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ; | + | * [http://www.ooty.com/todas.htm Ooty.com - Todas — A short introduction to the Todas.]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Ethnic group]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Anthropology]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credits|216421008}} | {{credits|216421008}} | ||

Latest revision as of 03:52, 1 May 2023

The Toda people designates a small pastoral community that live on the isolated Nilgiri plateau of Southern India. Prior to the late eighteenth century, the Toda coexisted locally with other communities, including the Badaga, Kota, and Kurumba, in a loose caste-like community organization. The Toda held the top ranking among those communities. The Toda population has hovered in the range 700 to 900 during the last century. Although an insignificant fraction of the large population of India, the Toda have attracted (since the late eighteenth century), "a most disproportionate amount of attention because of their ethnological aberrancy" and "their unlikeness to their neighbours in appearance, manners, and customs."[1] The study of their culture by anthropologists and linguists would prove important in the creation of the fields of social anthropology and ethnomusicology.

The revered place of the buffalo in Toda society represents a remarkable feature of their life. Over the centuries, the Toda came to rely heavily upon the buffalo for their livelihood. They created religious and social values around the buffalo, including their origin myth. The first sacred buffalo had been created by the gods before the first Toda man and woman. Kona Shastra, the annual sacrifice of a male buffalo constitutes their central religious ceremony. The person who tends the holy sacred buffalo, the divine milkman, has the highest position in Toda society. The Toda way of life has been threatened by contact with modern India, a shift from herding to agriculture, and a loss of grazing land as a result of the government of Tamil Nadu conducting a reforestation program. UNESCO has declared the Toda peoples home land, Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, and International Biosphere Reserve a World Heritage Site. The initiatives by UNESCO may help the Toda people preserve their traditional way of life. Yet, the conveniences of modern life, such has more comfortable housing and clothing, as well as the benefits of the Information Age, may hasten the demise of the Toda people's traditional religious beliefs and social practices.

Description

The Toda traditionally live in settlements consisting of three to seven small thatched houses, constructed in the shape of half-barrels and spread across the slopes of the pasture.[2] They traditionally trade dairy products with their Nilgiri neighbors.[2] Toda religion centers on the buffalo; consequently, they perform rituals for all dairy activities as well as for the ordination of dairymen-priests. The religious and funerary rites provide the social context in which the Toda compose and chant complex poetic songs about the cult of the buffalo.[2] Fraternal polyandry, fairly common in traditional Toda society, has now largely been abandoned.

During the last quarter of the twentieth century, agriculture by people moving into the area depleted some Toda pasture land.[2] Afforestation by the State Government of Tamil Nadu has also taken a toll on their grazing land. That has threatened to undermine Toda culture by greatly diminishing the buffalo herds. During the last decade, both Toda society and culture have also become the focus of an international effort at culturally sensitive environmental restoration.[3] The Toda lands now belong to the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO-designated International Biosphere Reserve. UNESCO has the area under consideration for selection as a World Heritage Site.[4]

Population

According to M.B. Emeneau, the successive decennial Census of India figures for the Toda are: 1871 (693), 1881 (675), 1891 (739), 1901 (807), 1911 (676) (corrected from 748), 1951 (879), 1961 (759), 1971 (812). These in his judgment:

Justifies concluding that a figure between 700 and 800 is likely to be near the norm, and that variation in either direction is due on the one hand to epidemic disaster and slow recovery thereafter (1921 (640), 1931 (597), 1941 (630)) or on the other hand to an excess of double enumeration (suggested already by census officers for 1901 and 1911, and possibly for 1951). Another factor in the uncertainty in the figures is the declared or undeclared inclusion or exclusion of Christian Todas by the various enumerators … Giving a figure between 700 and 800 is highly impressionistic, and may for the immediate present and future be pessimistic, since public health efforts applied to the community seem to be resulting in an increased birth rate and consequently, one would expect, in an increased population figure. However, earlier predictions that the community was declining were overly pessimistic and probably never well-founded.[1]

History

The origin of the Todas remains unclear. One of the original tribes, they have been inhabiting the highest regions of the Nilgiris mountain range and have remained secluded for a very long time. Around 1823, the Collector of Coimbatore, John Sullivan, took a fancy to their land and bought it from them for a mere one rupee. He established a town at the place named Udagamandalam on the land. The interaction with western civilization caused many changes in the lifestyle of the Todas.

Culture and society

The Toda dress consists of a single piece of cloth, worn like the plaid of a Scottish highlander. Cattle-herding and dairy-work constitute their sole occupation. They once practiced fraternal polyandry, a practice in which a woman marries all the brothers of a family, but no longer do so.[5] The ratio of females to males stands at about three to five. The Kota represent the most closely related people to the Toda, both ethnically and linguistically.

The Todas worship their dairy-buffaloes, but they have a whole pantheon of other gods. Kona Shastra, the annual sacrifice of a male buffalo calf, constitutes their only purely religious ceremony. Toda villages, called munds, usually consist of five buildings or huts, of which they use three as dwellings, one as a dairy and the other as a shelter for the calves at night. The inhabitants of a mund, generally related, consider themselves one family. The Todas numbered 807 in 1901, and their current population stands at around 1,100.[6]

Religion

According to the Todas, the goddess Teikirshy and her brother first created the sacred buffalo and then the first Toda man. They created the first Toda woman from the right rib of the first Toda man. The Toda religion also forbids them from walking across bridges, rivers must be crossed on foot, or swimming.

The Todas especially revere the Pandavas, although little evidence exists that the believe in the rest of the Hindu mythology. Toda temples, constructed in a circular pit lined with stones, look quite similar in appearance and construction to Toda huts.

From Frazer's Golden Bough, 1922:

Among the Todas of Southern India the holy milkman, who acts as priest of the sacred dairy, is subject to a variety of irksome and burdensome restrictions during the whole time of his incumbency, which may last many years. Thus he must live at the sacred dairy and may never visit his home or any ordinary village. He must be celibate; if he is married he must leave his wife. On no account may any ordinary person touch the holy milkman or the holy dairy; such a touch would so defile his holiness that he would forfeit his office. It is only on two days a week, namely Mondays and Thursdays, that a mere layman may even approach the milkman; on other days if he has any business with him, he must stand at a distance (some say a quarter of a mile) and shout his message across the intervening space. Further, the holy milkman never cuts his hair or pares his nails so long as he holds office; he never crosses a river by a bridge, but wades through a ford and only certain fords; if a death occurs in his clan, he may not attend any of the funeral ceremonies, unless he first resigns his office and descends from the exalted rank of milkman to that of a mere common mortal. Indeed it appears that in old days he had to resign the seals, or rather the pails, of office whenever any member of his clan departed this life. However, these heavy restraints are laid in their entirety only on milkmen of the very highest class

Language

The Toda language belongs to the Dravidian family. Like their ethnology, they have aberrant language and difficult phonologically. Toda (along with their neighbors, the Kota) belongs to the the southern subgroup of the historical family proto-South-Dravidian, splitting off from South Dravidian after Kannada and Telegu, but before Malayam. In modern linguistic terms, the aberrancy of Toda results from disproportionately numerous rules, both early and recent in their ordering, not shared by the other South Dravidian languages (and shared only to a small extent by Kota).[1]

Toda dwellings and lifestyle

The Todas live in small hamlets called munds. The Toda huts, of an oval, pent-shaped construction, usually stand ten feet (3 m) high, eighteen feet (5.5 m) long and nine feet (2.7 m) wide. Built of bamboo fastened with rattan and thatched, a wall of loose stones encloses each hut. Dressed stones (mostly granite) usually make up the front and back of the hut. Each hut has only a tiny entrance at the front—about 3 feet (90 cm) wide, 3 feet (90 cm) tall. That unusually small entrance serves as a means of protection from wild animals. The Toda art forms, a kind of rock mural painting, decorates the front portion of the hut. Thicker bamboo canes arch to give the hut its basic tent shape. Tied close and parallel to each other, thinner bamboo canes lay over that frame. Dried grass stacks were laid over thatas thatch.

The forced interaction with civilization has caused a lot of changes in the lifestyle of the Todas. The Todas used to be a pastoral people but now increasingly venture into agriculture and other occupations. They used to be strict vegetarians but some can be now be seen eating non-vegetarian food. Although many Toda have abandoned their traditional distinctive huts for concrete houses,[5] a movement has gained momentum to build tradition barrel-vaulted huts. During the last decade, forty new huts have been built and many Toda sacred dairies have been renovated.[7]

See Also

- Nilgiris district

- Karnataka

- Polyandry

- Indian vernacular architecture

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 (Emeneau 1984, pp. 1-2)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Encyclopædia Britannica, Toda.

- ↑ Chhabra 2006.

- ↑ UNESCO, World Heritage sites, Tentative lists, April 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 (Walker 2004).

- ↑ W.H.R. Rivers, The Todas (1906).

- ↑ (Chhabra 2005) Quote: "… over the past ten years, we have approached government and private agencies for sponsoring traditional houses. Today, we have been able to assist in funding over forty barrel-vaulted houses. Added to these are the scores of existing temples—two are conical and the rest barrel-vaulted."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chhabra, Tarun. "How Traditional Ecological Knowledge addresses Global Climate change: The perspective of the Todas—the indigenous people of the Nilgiri hills of South India." Proceedings of the Earth in Transition: First World Conference (2005)

- Chhabra, Tarun. "Restoring the Toda Landscapes of the Nilgiri Hills in South India. " Plant Talk 44 (2006)

- Emeneau, M.B. "Oral Poets of South India: Todas." Journal of American Folklore 71 (281) (1958): 312-324.

- Emeneau, M.B. Toda Songs. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971. ISBN 0198151292.

- Emeneau, Murray Barnson. "Ritual Structure and Language Structure of the Todas." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, N.S., 64: 6. 1974. ISBN 0871696460.

- Emeneau, Murray Barnson. "Toda grammar and texts." Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, 155. Philadelphia: Soc, 1984. ISBN 0871691558.

- Emeneau, M. B. "A Century of Toda Studies: Review of The Toda of South India: A New Look by Anthony R. Walker; M. N. Srinivas." Journal of the American Oriental Society 108(4) (1988): 605-609.

- Rivers, W.H.R. The Todas. London: Macmillan, 1906. OCLC 3359858.

- Rivers, William H.R. "The Todas Anthropological Publications (1909). Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- Walker, Anthony R. "The Truth About the Toda." Frontline, The Hindu (2004)

- Walker, Anthony R. Between Tradition and Modernity and Other Essays on the Toda of South India. Delhi: B.R. Pub. Corp, 1998. ISBN 8170189160.

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.