Joplin, Scott

Cheryl Lau (talk | contribs) |

({{Contracted}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{claimed}}{{submitted}} | + | {{claimed}}{{Contracted}}{{submitted}} |

{{epname|Joplin, Scott}} | {{epname|Joplin, Scott}} | ||

{{Infobox Biography | {{Infobox Biography | ||

Revision as of 15:16, 26 February 2007

| Scott Joplin |

|---|

| Born |

| June 1867 - January 1868 East Texas |

| Died |

| April 1, 1917 New York City, New York |

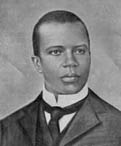

Scott Joplin (born between June 1867 and January 1868 died April 1, 1917) was a African-American and composer of ragtime music. Ragtime existed before jazz, having the same unusual beats and strong rhythm. Scott is considered the "Father of Ragtime" by many, not because he created it, but because of his excellent ability to express it and bring it to the attention of music lovers everywhere. One of his most noteable pieces, "The Entertainer", was popularized by the successful movie "The Sting", starring Steve McQueen. He remains the best-known ragtime figure and is regarded as one of the three most important composers of Classic Rag, along with James Scott and Joseph Lamb. He is also known for his passion for African-Americans which he demonstrated in the opera "The Honored Guest" and "Treemonisha".

Early years

Joplin was born in East Texas, near Linden, Texas [1], to Florence Givins Joplin and Giles (sometimes listed as "Jiles") Joplin. While for many years his date of birth was thought to be November 24, 1868, new research by ragtime historian Ed Berlin, has revealed that this is inaccurate. [2] – A census taken in 1870, put his birthdate around one year earlier than originally noted.[3] He was the second of six children, Scott having three brothers and two sisters. His father was a farmer and a former slave. Both of his parents were musically talented. His father played the fiddle and his mother sang and played banjo, creating for Scott an early exposure to music and rhythm.

Around 1871 the Joplin family moved to Texarkana, Texas. Scott's mother began cleaning homes after his father left the family. Scott came along to practice his music on the pianos of her employers. Showing musical ability at an early age, the young Joplin received piano lessons for free, from a German music teacher, Julius Weiss, who heard of his talent. These lessons gave Scott a well-rounded knowledge of classical music form. This is something that would serve him well in later years and fuel his ambition to create a "classical" form of ragtime. By 1882 his mother had purchased a piano.

Joplin studied under many piano teachers, working well with them, however he kept his own style. When his mother died in the late 1880's, Scott left home to become a professional musician. As a teenager, he played in churches, bars, and brothels - the only places a black musician could perform in late Ninetenth Century America.

Joplin's musical talents were varied. He joined, or formed, various quartets and other musical groups while traveling around the Midwest. In the Queen City Concert Band he played the coronet, and was also known to be part of a minstrel troupe in Texarkana, around 1891. Joplin organized 'The Texas Medley Quartette' and helped them sing thier way back to Syracuse,NY. His perfomances became very popular with some New York businessmen in Syracuse, which lead to their issueing his first two songs, Please Say You Will and A Picture of Her Face.

As he traveled the South, he absorbed both black and white ragtime. Ragtime evolved from the old slave songs and combined a syncopated and varied rhythm pattern with the melody. It was often called "ragging" the song, and was especially popular with dance music. In fact, dances were often called "rags". When not traveling, his home was in Sedalia, Missouri, where he moved in 1894. There he worked as a pianist in the Maple Leaf and Black 400 clubs which were social clubs for "respectable black gentlemen." He also taught several local musicians, among them were Scott Hayden and Arthur Marshall, whom he would later colaborate with on several rags.

It was around 1896 when Joplin attended music classes at George R. Smith College in Sedalia, an institution for African-Americans established by the Methodist Church. Unfortunately the college, and it's records, were distroyed in a fire in 1925, so there is no record of the extent of his education there. It is accepted that his abilities in music notation were still lacking until the end of the 1890's.

His inabilities did not stop him, however, for in 1896 Joplin published two marches and a waltz. Two years later he succeeded in selling his first piano rag, Original Rags, a colaboration with arranger, Charles N. Daniels, and publisher, Carl Hoffman.

Success

By 1898 Joplin had sold six pieces for the piano, 'Original Rags,' being the only ragtime piece. The other five were the two songs mentioned previously, two marches, and a waltz.

In 1899, Scott Joplin sold what would become his most famous piece, Maple Leaf Rag to John Stark & Son, a Sedalia music publisher. Joplin received a one-cent royalty for each copy and ten free copies for his own use, as well as an advance. It has been estimated that Joplin made $360 per year on this piece in his lifetime. It was with these publishers that Joplin met and befriended Joseph Lamb. Lamb's famous Sensations (1908) was published after Joplin's recommendation.

Maple Leaf Rag boosted Joplin to the top of the list of ragtime performers and moved ragtime into prominence as a musical form.

With a growing national reputation on the success of Maple Leaf Rag, Joplin moved to St. Louis, Missouri in early 1900 with his new wife, Belle. While living there between 1900 and 1903, he produced some of his best-known works, including The Entertainer, Elite Syncopations, March Majestic and Ragtime Dance.

Joplin is also famous for composing the ragtime opera A Guest of Honor, in 1903, which shocked the nation. It portrayed the dinner between Brooker T. Washinton and President Roosevelt at the White House, in l901, which put African-Americans on equal footing with other "white" Americans.[4] The score to A Guest of Honor, is lost.

Treemonisha, one of Joplin's operas, became a great success posthumously. It brought to light the situation of the African-Americans of his day, and memorialized the idea that education was the only way to overcome ignorance and superstitions. He was a great advocate of education.

Joplin had several marriages. Perhaps his dearest love, Freddie Alexander, died at age twenty of complications resulting from a cold, just two months after their wedding. The first work copyrighted after Freddie's death, Bethena (1905), is a very sad, musically complex ragtime waltz.

After months of faltering, Joplin continued writing and publishing. In those days before recorded music, he was a best-selling composer of sheet music. Joplin, with much hard work, produced the previously unrecognized but award-winning opera Treemonisha.

Illness

Joplin wanted to experiment further with compositions like Treemonisha, but by 1916 he was suffering from the effects of terminal syphilis. He suffered later from dementia, paranoia, paralysis and other symptoms. Despite his ill health, he recorded six piano rolls that year — Maple Leaf Rag (for Connorized and Aeolian companies), Something Doing, Magnetic Rag, Ole Miss Rag, Weeping Willow Rag and Pleasant Moments - Ragtime Waltz (all for Connorized). These are the only records of his playing we have, and are interesting for the embellishments added by Joplin to his performances. The roll of Pleasant Moments was thought lost until August 2006, when a piano roll collector in New Zealand discovered a surviving copy. It has been claimed that the uneven nature of some of Joplin's piano rolls, such as one of the recordings of Maple Leaf Rag mentioned above, documented the extent of Joplin's physical deterioration due to syphilis. A comparison of the two Maple Leaf Rag player-piano rolls made by Joplin in 1916, one in April the other in June, has been described as "...shocking. The second version is disorganized and completely distressing to hear." [5] However, the irregularities may also be due to the primitive technology used to record the rolls, although rolls recorded by other artists around the same time are noticeably smoother.

In mid-January, 1917 Joplin was hospitalized at Manhattan State Hospital in New York City, and friends recounted that he would have bursts of lucidity in which he would jot down lines of music hurriedly before relapsing. Joplin died there, on April 1, 1917, near the age of 50.

Joplin's death did not make the headlines for two reasons: Ragtime was quickly losing ground to jazz and the United States would enter World War I within days. He was buried in St. Michael's Cemetery in the Astoria section of Queens, NY.

Joplin's musical papers, including unpublished manuscripts, were willed to Joplin's friend and the executor of his will, musician and composer Wilber Sweatman. Sweatman took care of these papers and generously shared access to them to those who inquired. However, these were unfortunately few, since Joplin's music had come to be considered passé. After Sweatman's death in 1961 the papers were last known to go into storage during a legal battle among Sweatman's heirs; their current location is not known, nor even if they still exist.

There was, however, an important find in 1971: a piano-roll copy of the lost Silver Swan Rag, cut sometime around 1914. It had not been published in sheet-music form in Joplin's lifetime. Before this, his only posthumously published piece had been Reflection Rag, published by Stark in 1917, from an older manuscript he'd kept back.

Legacy and revival

After his death, Joplin's music and ragtime in general waned in popularity as new forms of musical styles, such as jazz and novelty piano emerged. However, a number of revivals of ragtime have occurred since.

In the early 1940s, many jazz bands began to include ragtime in their repertoire and released ragtime recordings on 78 RPM records. In 1970, Joshua Rifkin released a Grammy Award nominated recording of Joplin's rags on the classical label Records|Nonesuch.[6] In 1972, Joplin's opera Treemonisha was finally staged at Morehouse College in Atlanta. Marvin Hamlisch's adaptation of the Joplin rag "The Entertainer," taken from the Oscar-winning film The Sting, reached #3 on the Billboard Hot 100 music chart in 1974. Ironically, Hamlisch's slightly-abbreviated arrangements and performances of Joplin's rags for The Sting, were ahistorical, as the film was set in the 1930s, well past the peak of the ragtime era.

In 1974, Kenneth MacMillan created a ballet for the Royal Ballet, Elite Syncopations, based on tunes by Joplin, Max Morath and others. It is still performed occasionally.

Scott Joplin was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for his special contribution to American music. [7] He also has a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame. Motown Productions produced a Scott Joplin biographical film starring Billy Dee Williams as Joplin, which was released by Universal Pictures in 1977.

In 1983, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp of the composer as part of its Black Heritage commemorative series.

Joplin's music

Even at the time of publication, Joplin's publisher John Stillwell Stark was claiming that the rags had obtained classical status, and "lifted ragtime from its low estate and elevated it to the level of Beethoven and Bach"[8]. Later critics also saw merit in Joplin's compositions:

He combined the traditions of Afro-American music folk music with nineteenth-century European romanticism; he collected the black Midwestern Folk rag ideas as raw material for the creation of original strains. Thus, his rags are the most heavily pentatonic, with liberal use of blue notes and other outstanding features that characterize black folk music. In this creative synthesis, . . . the traditional march became the dominant form, and the result was a new art form, the classic rag – a unique conception which paradoxically both forged the way for early serious ragtime composition, and, at the same time, developed along insular lines, away from most other ragtime playing and composing.[9]

Ragtime was claimed to be a precursor to jazz, the latter containing improvisations and more blue notes. [1].

A note on tempo

Joplin left little doubt as to how his compositions should be performed: as a precaution against the prevailing tendency of the day to up the tempo, he explicitly wrote in many of his scores that "ragtime should never be played fast." According to Joplin biographer Rudi Blesh,http://cnx.org/content/m10878/latest/

Joplin's injunction needs to be read in the light of his time, when a whole school of "speed" players ... were ruining the fine rags. Most frequently felled by this quack-virtuoso musical mayhem was the Maple Leaf Rag. Joplin's concept of "slow" was probably relative to the destructive prestos of his day.[10]

Works by Scott Joplin

Inconsistencies exist between certain titles and subtitles, and their respective cover titles, possibly reflecting an editorial casualness... the substitution of terms would also indicate that the designations: cakewalk, march, two-step, rag, and slow drag were interchangeable, inasmuch as they alluded to a genre of music in duple meter to which a variety of dance steps might be performed.[11] There are also inconsistencies between the publishing date, and registering of copyright. In some instances, copyright notices were not registered. In all cases, musical compositions are listed by date of publication using their cover titles and subtitles[12].

- "Please Say You Will" (1895)

- "A Picture of Her Face" (1895)

- "Great Crush Collision" – March (1896)

- "Combination March" (1896)

- "Harmony Club Waltz" (1896)

- "Original Rags" (1899); arranged by Charles N. Daniels

- "Maple Leaf Rag" (1899)

- "Swipsey" – Cake Walk (1900) – with Arthur Marshall

- "Peacherine Rag" (1901)

- "Sunflower Slow Drag" – A Rag Time Two Step (1901) – with Scott Hayden

- "Augustan Club Waltz" (1901)

- "The Easy Winners" – Ragtime Two Step (1901)

- "Cleopha" – March and Two Step (1902)

- "A Breeze From Alabama" – Ragtime Two Step (1902)

- "Elite Syncopations" (1902)

- "The Entertainer" – Ragtime Two Step (1902)

- "I Am Thinking of My Pickanniny Days" (1902); lyrics by Henry Jackson

- "March Majestic" (1902)

- "The Strenuous Life" – Ragtime Two Step (1902)

- "The Ragtime Dance" (1902); lyrics by Scott Joplin

- "Something Doing" – Cake Walk March (1903) – with Scott Hayden

- "Weeping Willow" – Ragtime Two Step (1903)

- "Little Black Baby" (1903); lyrics by Louis Armstrong Bristol

- "Palm Leaf Rag" – A Slow Drag (1903)

- "The Sycamore" – A Concert Rag (1904)

- "The Favourite" – Ragtime Two Step (1904)

- "The Cascades" – A Rag (1904)

- "The Chrysanthemum" – An Afro-Intermezzo (1904)

- "Bethena" – A Concert Waltz (1905)

- "Binks' Waltz" (1905)

- "Sarah Dear" (1905); lyrics by Henry Jackson

- "Rosebud" – Two Step (1905)

- "Leola" – Two Step (1905)

- "Eugenia" (1906)

- "The Ragtime Dance" – A Stop-Time Two Step (1906)

- "Antoinette" – March and Two Step (1906)

- "Nonpareil (None to Equal) (1907)

- "When Your Hair Is Like the Snow" (1907) lyrics by "Owen Spendthrift"

- "Gladiolus Rag" (1907)

- "Searchlight Rag" – A Syncopated March and Two Step (1907)

- "Lily Queen" – Ragtime Two-Step (1907) – with Arthur Marshall

- "Rose Leaf Rag" – Ragtime Two-Step (1907)

- "Lily Queen" (1907) with Arthur Marshall

- "Heliotrope Bouquet" – A Slow Drag Two-Step (1907) – with Louis Chauvin

- "School of Ragtime" – 6 Exercises for Piano (1908)

- "Fig Leaf Rag" (1908)

- "Wall Street Rag" (1908)

- "Sugar Cane" – Ragtime Classic Two Step (1908)

- "Sensation" – A Rag (1908); by Joseph F. Lamb, arranged by Scott Joplin

- "Pine Apple Rag" (1908)

- "Pleasant Moments" – Ragtime Waltz (1909)

- "Solace" – A Mexican Serenade (1909)

- "Country Club" – Rag Time Two Step (1909)

- "Euphonic Sounds" – A Syncopated Novelty (1909)

- "Paragon Rag" – A Syncopated Novelty (1909)

- "Stoptime Rag" (1910)

- "Treemonisha" (1911)

- "Felicity Rag" (1911) – with Scott Hayden

- "Scott Joplin's New Rag" (1912)

- "Kismet Rag" (1913) – with Scott Hayden

- "Magnetic Rag" (1914)

- "Reflection Rag" – Syncopated Musings (1917)

- "Silver Swan Rag" (1971) (attributed to Scott Joplin)

Samples

- Maple Leaf Rag first section, Ogg Vorbis format, 17 seconds, 148 KB (info...)

- Maple Leaf Rag. This is a recording of a player-piano roll made by Joplin for the Connorized piano roll company in April 1916.

- Pleasant Moments, 2.1Mb. This is a recording of the Connorized piano roll made by Joplin in April 1916, and thought lost until mid-2006.

Further reading

- Berlin, Edward A., King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era, (the most authoritative book on Joplin's life), NY: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-195-08739-9

- Gammond, Peter, "Scott Joplin and the Ragtime Era", NY: St. Martin's Press, 1975. OCLC 1582739

- Haskins, James and Benson, Kathleen, "Scott Joplin", Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1978. ISBN 0-385-11155-X

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Texas Music History Online - Scott Joplin. Retrieved 2006-11-22.

- ↑ A Biography of Scott Joplin. The Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation.

- ↑ http://www.scottjoplin.org/biography.htm

- ↑ http://www.scottjoplin.org/biography.htm

- ↑ Rudi Blesh, pxxxix, "Scott Joplin: Black-American Classicist", Introduction to Scott Joplin Complete Piano Works, New York Public Library, 1981

- ↑ http://theenvelope.latimes.com/extras/lostmind/year/1971/1971grammy.htm

- ↑ http://www.pulitzer.org/cgi-bin/year.pl?type=w&year=1976&FormsButton2=Retrieve

- ↑ (Stark ad, page 23, in Ragtime Review (Vol. 1, No. 2: January 1915), quoted in "Scott Joplin - The King of Ragtime Writers" by Ted Tjaden http://www.ragtimepiano.ca/rags/joplin.htm.

- ↑ p83, David A. Jasen, and Trebor Jay Tichenor. Rags and Ragtime: A Musical History. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1978

- ↑ Rudi Blesh, pxxix, "Scott Joplin: Black-American Classicist", Introduction to Scott Joplin Complete Piano Works, New York Public Library, 1981

- ↑ Vera Brodsky Lawrence, Editor's Note pix, Scott Joplin Complete Piano Works, New York Public Library, 1981.

- ↑ Index p. 325, Scott Joplin Complete Piano Works, New York Public Library, 1981.

External links

- Joplin Myths

- Scott Joplin: King of Ragtime (1868-1917)

- A good overview of Joplin's life and work

- Brief biography of Scott Joplin

- Joplin on Famous Texans site

- Joplin at St. Louis Walk of Fame

- Scott Joplin at Find-A-Grave

- African Heritage A site dedicated to African heritage in Classical music, which includes over 50 other composers.

- Maple Leaf Rag A site dedicated to 100 years of the Maple Leaf Rag.

Recordings and sheet music

- The Mutopia project has freely downloadable piano scores of several of Joplin's works

- Free scores by Scott Joplin in the Werner Icking Music Archive

- Kunst der Fuge: Scott Joplin - MIDI files (live and piano-rolls recordings)

- Scott Joplin at PianoVault has sheet music and MIDIs for all of Joplin's piano music

- Scott Joplin - German site with free sheet music and MIDI files

- John Roache's site has excellent MIDI performances of ragtime music by Joplin and others

- Scott Joplin, Complete Piano Rags, David A Jasen, 1988, ISBN 0-486-25807-6