Difference between revisions of "Sarcophagus" - New World Encyclopedia

Nick Perez (talk | contribs) |

Nick Perez (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

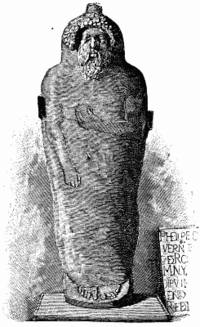

| − | + | [[Image:Anthropoid sarcophagus discovered at Cadiz - Project Gutenberg eText 15052.png|200px|thumb|right|Anthropoid sarcophagus discovered at [[Cádiz]]]] | |

| − | [[Image: | + | A '''sarcophagus''' (plural:'''sarcophagi''') is an above ground stone container for a [[coffin]] or body, that often is decorated with art, inscriptions and carvings. First used in Anciet [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]] and [[Ancient Greece|Greece]], the sarcophagus gradually became popular throughout the ancient world and carried over through the later years of [[Europe|European]] society, often used for high status members of the [[clergy]], [[government]] or [[aristocracy]]. |

| − | A '''sarcophagus''' is | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Eytmology== | ==Eytmology== | ||

| + | The word comes from the [[Greek language|Greek]] "sarx" meaning "flesh," and "phagien" meaning "to eat," so that ''sarcophagus'', literally translates as "eater of flesh." The 5th century B.C.E. [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] historian, [[Herodotus]], noted that early sarcophagi (the plural) were carved from a special kind of rock that consumed the flesh of the [[corpse]] inside. In particular, coffins made of a [[limestone]] from [[Assus]] in the [[Troad]] known as ''lapis Assius'' had the property of consuming the bodies placed within them, and therefore was also called ''sarkophagos lithos'' (flesh-eating stone). All coffins made of limestone have this property to a greater or lesser degree, and the name eventually came to be applied to stone coffins in general.<ref>sarcophagus. (n.d.). The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Retrieved September 12, 2007, from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/sarcophagus</ref> | ||

| + | [[Image:Detail sarcophagus Istanbul Arkeoloji Muzesi.jpg|left|200px|thumb|Detail of a stone sarcophagus in the [[Istanbul Archaeology Museum]] showing a hunting scene.]] | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| − | [[ | + | Sarcophagi differ in detail from one culture to another. They are almost always made of stone, limestone being the most popular, but also sometimes of granite, sandstone, or marble. Sarcophagi were usually made by being carved, decorated or built ornately. Some were built to be freestanding above ground, as a part of an elaborate tomb or tombs. Others were made for burial, or were placed in [[crypt]]s. |

| + | |||

| + | The first were usually simple box shapes that could be inscribed upon. This was common in ancient Egypt, were a sarcophagus was usually the external layer of protection for a [[royal]] [[Mummy#Mummies_in_ancient_Egypt|mummy]], with several layers of coffins nested within, that also to protect dead bodies. Over time, the artistry on these boxes became more detailed, to include inset scupltures, seem frequently in [[Ancient Rome|Roman]], and later, [[Holy Roman Church|Catholic]] sarcophagi. The scupltures would often depict a scene from mythology, or in the case of [[Catholicism]], scenes from the [[Bible]]. Some sarcophagi actually began to take on contours similar to the human body, and often were given a painted or sculpted face. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Examples== | ==Examples== | ||

| − | === | + | Below are a few examples of famous scarophagi from around the world. |

| + | |||

| + | ===Ahiram=== | ||

[[Image:Ahiram sarcophag from Biblos XIII-XBC.jpg|thumb|175px|Sarcophag of Ahiram, King of Biblos (Phoenicia) in XIII-X c. BC. Kept in Beirut National Museum]] | [[Image:Ahiram sarcophag from Biblos XIII-XBC.jpg|thumb|175px|Sarcophag of Ahiram, King of Biblos (Phoenicia) in XIII-X c. BC. Kept in Beirut National Museum]] | ||

| − | + | One of the ancient kings of [[Phoenica]], [[Ahiram]] ('''King of Biblos''' as he was known then) was sealed for in a Late Bronze Age [[sarcophagus]] at some point during the early 10th century B.C.E.<ref>''The Cambridge Ancient History'' ed by Iorwerth Eiddon et al. 2nd ed. Vol. II pt.2, Cambridge University Press, 1975. ISBN 0521086914 [http://books.google.com/books?id=n1TmVvMwmo4C&pg=PA521&lpg=PA521&dq=ahiram&source=web&ots=f_0M3z8nhG&sig=qp_LHve_bF5XPXBGrPpSwvUqLRM#PPA521,M1 Google Books], p 521.</ref> Upon discovery, the sarcophagus was subsequently moved to the [[Beirut National Museum]], where it is now on display. To [[archaeology|archaeologists]], the sarcophagus represented a rare discovery in early Phoenician art and writing. It also is a classical example of the blending of styles, in which the box style sarcophagus is used, but intricate artwork is added around the sides. | |

| − | The engraving text, in the [[Phoenician language]] says: "Coffin which Itthobaal son of Ahiram, king of Byblos, made for Ahiram his father, when he placed him for eternity. Now, if a king among kings, or a governor among governors or a commander of an army should come up against Byblos and uncover this coffin, may the sceptre of his rule be torn away, may the throne of his kingdom be overturned and may peace flee from Byblos. And as for him, may his inscription be effaced". This is apparently the oldest inscription in the [[Phoenician alphabet]].<ref> | + | The engraving text, in the [[Phoenician language]] says: "Coffin which Itthobaal son of Ahiram, king of Byblos, made for Ahiram his father, when he placed him for eternity. Now, if a king among kings, or a governor among governors or a commander of an army should come up against Byblos and uncover this coffin, may the sceptre of his rule be torn away, may the throne of his kingdom be overturned and may peace flee from Byblos. And as for him, may his inscription be effaced". This is apparently the oldest inscription in the [[Phoenician alphabet]].<ref> Beruit National Museum [[http://www.beirutnationalmuseum.com/e-collection-bronze.htm"The Sarcophagus of King Ahiram"]] Retrieved September 12, 2007 </ref> |

===Sarcophagus of the Spouses=== | ===Sarcophagus of the Spouses=== | ||

[[Image:Banditaccia Sarcofago Degli Sposi.jpg|thumb|150px|The [[Etruscan]] ''[[sarcophagus of the spouses]]'', at the [[National Etruscan Museum]]]] | [[Image:Banditaccia Sarcofago Degli Sposi.jpg|thumb|150px|The [[Etruscan]] ''[[sarcophagus of the spouses]]'', at the [[National Etruscan Museum]]]] | ||

| − | The "'''Sarcophagus of the Spouses'''" (Italian: ''Sarcofago degli Sposi'') is a late [[6th century B.C.E.]] [[Etruscan art|Etruscan]] [[anthropoid]] [[sarcophagus]]. It is 1.14 m high by 1.9 m wide, and is made of painted [[terracotta]]. It depicts a married couple reclining at a banquet together in the afterlife (in a scene similar to that from contemporary Greek vases) and was found in 19th century excavations at the [[necropolis]] of [[Cerveteri]] (ancient [[Caere]]). It is now in the [[National Etruscan Museum]] of [[Villa Giulia]], [[Rome]]. | + | The "'''Sarcophagus of the Spouses'''" (Italian: ''Sarcofago degli Sposi'') is a late [[6th century B.C.E.]] [[Etruscan art|Etruscan]] [[anthropoid]] [[sarcophagus]]. It is 1.14 m high by 1.9 m wide, and is made of painted [[terracotta]]. It depicts a married couple reclining at a banquet together in the afterlife (in a scene similar to that from contemporary Greek vases) and was found in 19th century excavations at the [[necropolis]] of [[Cerveteri]] (ancient [[Caere]]). It is now in the [[National Etruscan Museum]] of [[Villa Giulia]], [[Rome]].<ref> (2004)Kozlowski, Jamie. [[http://domspe.org/etruscans/obsession.html"Obsession With Death"]] Retrieved September 12, 2007 </ref> |

| − | The smiling faces with their almond shaped eyes and long braided hair, as well as the shape of the feet of the bed, reveal Greek influence. The marked contrast between the high relief busts and the very flattened legs is typically Etruscan. The Etruscan artist's interest focused on the upper half of the figures, especially on the vibrant faces and gesticulating arms. It is very similar to the Sarcophagus from Cerveteri, perhaps by the same artist. Both portray the affection of a man and a woman, an image never before seen in the Greek culture. | + | The smiling faces with their almond shaped eyes and long braided hair, as well as the shape of the feet of the bed, reveal Greek influence. The marked contrast between the high relief busts and the very flattened legs is typically Etruscan. The Etruscan artist's interest focused on the upper half of the figures, especially on the vibrant faces and gesticulating arms. It is very similar to the Sarcophagus from Cerveteri, perhaps by the same artist. Both portray the affection of a man and a woman, an image never before seen in the Greek culture. |

===St. Andrew=== | ===St. Andrew=== | ||

| Line 68: | Line 67: | ||

Image:Sarcophagus Maconiana Severiana Getty Villa 83.AA.275.jpg|Weddings of Dionysos and Ariadne. The Latin inscription identifies the girl for whom this sarcophagus was made as Maconiana Severiana, member of a wealthy senatorial family. Ariadne's face was probably left unfinished to be completed as a portrait of Maconiana | Image:Sarcophagus Maconiana Severiana Getty Villa 83.AA.275.jpg|Weddings of Dionysos and Ariadne. The Latin inscription identifies the girl for whom this sarcophagus was made as Maconiana Severiana, member of a wealthy senatorial family. Ariadne's face was probably left unfinished to be completed as a portrait of Maconiana | ||

</Gallery> | </Gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Footnotes== | ||

| + | <References/> | ||

| + | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 13:41, 12 September 2007

A sarcophagus (plural:sarcophagi) is an above ground stone container for a coffin or body, that often is decorated with art, inscriptions and carvings. First used in Anciet Egypt and Greece, the sarcophagus gradually became popular throughout the ancient world and carried over through the later years of European society, often used for high status members of the clergy, government or aristocracy.

Eytmology

The word comes from the Greek "sarx" meaning "flesh," and "phagien" meaning "to eat," so that sarcophagus, literally translates as "eater of flesh." The 5th century B.C.E. Greek historian, Herodotus, noted that early sarcophagi (the plural) were carved from a special kind of rock that consumed the flesh of the corpse inside. In particular, coffins made of a limestone from Assus in the Troad known as lapis Assius had the property of consuming the bodies placed within them, and therefore was also called sarkophagos lithos (flesh-eating stone). All coffins made of limestone have this property to a greater or lesser degree, and the name eventually came to be applied to stone coffins in general.[1]

Description

Sarcophagi differ in detail from one culture to another. They are almost always made of stone, limestone being the most popular, but also sometimes of granite, sandstone, or marble. Sarcophagi were usually made by being carved, decorated or built ornately. Some were built to be freestanding above ground, as a part of an elaborate tomb or tombs. Others were made for burial, or were placed in crypts.

The first were usually simple box shapes that could be inscribed upon. This was common in ancient Egypt, were a sarcophagus was usually the external layer of protection for a royal mummy, with several layers of coffins nested within, that also to protect dead bodies. Over time, the artistry on these boxes became more detailed, to include inset scupltures, seem frequently in Roman, and later, Catholic sarcophagi. The scupltures would often depict a scene from mythology, or in the case of Catholicism, scenes from the Bible. Some sarcophagi actually began to take on contours similar to the human body, and often were given a painted or sculpted face.

Examples

Below are a few examples of famous scarophagi from around the world.

Ahiram

One of the ancient kings of Phoenica, Ahiram (King of Biblos as he was known then) was sealed for in a Late Bronze Age sarcophagus at some point during the early 10th century B.C.E.[2] Upon discovery, the sarcophagus was subsequently moved to the Beirut National Museum, where it is now on display. To archaeologists, the sarcophagus represented a rare discovery in early Phoenician art and writing. It also is a classical example of the blending of styles, in which the box style sarcophagus is used, but intricate artwork is added around the sides.

The engraving text, in the Phoenician language says: "Coffin which Itthobaal son of Ahiram, king of Byblos, made for Ahiram his father, when he placed him for eternity. Now, if a king among kings, or a governor among governors or a commander of an army should come up against Byblos and uncover this coffin, may the sceptre of his rule be torn away, may the throne of his kingdom be overturned and may peace flee from Byblos. And as for him, may his inscription be effaced". This is apparently the oldest inscription in the Phoenician alphabet.[3]

Sarcophagus of the Spouses

The "Sarcophagus of the Spouses" (Italian: Sarcofago degli Sposi) is a late 6th century B.C.E. Etruscan anthropoid sarcophagus. It is 1.14 m high by 1.9 m wide, and is made of painted terracotta. It depicts a married couple reclining at a banquet together in the afterlife (in a scene similar to that from contemporary Greek vases) and was found in 19th century excavations at the necropolis of Cerveteri (ancient Caere). It is now in the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia, Rome.[4]

The smiling faces with their almond shaped eyes and long braided hair, as well as the shape of the feet of the bed, reveal Greek influence. The marked contrast between the high relief busts and the very flattened legs is typically Etruscan. The Etruscan artist's interest focused on the upper half of the figures, especially on the vibrant faces and gesticulating arms. It is very similar to the Sarcophagus from Cerveteri, perhaps by the same artist. Both portray the affection of a man and a woman, an image never before seen in the Greek culture.

St. Andrew

The Saint Andrews Sarcophagus is a Pictish monument dating from the middle of the 8th century. The sarcophagus was recovered beginning in 1833 during excavations by St Andrew's Cathedral, but it was not until 1922 that the surviving components were reunited. The sarcophagus is currently on display at the Cathedral museum in St Andrews, close to the site of its discovery. As originally constructed the sarcophagus would have comprised two side panels, two end panels, four corner pieces and a roof slab. The roof slab is entirely missing, as are most of one side and one end panel and a corner piece so that the extant sarcophagus is essentially L-shaped. The external dimensions of the sarcophagus are 177cm by 90cm and a height of 70cm. The stone used is a local sandstone.

The surviving side panel shows, from right to left, a figure breaking the jaws of a lion, a mounted hunter with his sword raised to strike a leaping lion, and hunter on foot, armed with a spear and assisted by a hunting dog, about to attack a wolf. Although it is not certain that the first two figures represent the same person, 19th century illustrations depict them as if they are. The surviving end panel is much simpler, essentially a cross with four small panels between the arms. The fragments of the missing end panel are similar, but not identical, to the surviving one.

Merenptah

Tomb KV8, located in the Valley of the Kings, was used for the burial of Pharaoh Merenptah of Ancient Egypt's Nineteenth Dynasty.

The burial chamber, located at the end of 160 metres of corridor, originally held a set of four nested sarcophagi. The outer one of these was so voluminous that parts of the corridor had to have their pillars demolished and rebuilt to allow it to be brought in.

Italy

an Ancient Roman christian sarcophagus dating from the 4th century. It is preserved beneath the pulpit of Sant'Ambrogio basilica in Milan, Italy. Picture by Giovanni Dall'Orto, April 25 2007. The so-called "Sarcofago di Stilicone" ("Stilicho's sarcophagus") is an Ancient Roman paleochristian sarcophagus dating from around 385 C.E., sculpted for a high-rank military authority and his wife. It is preserved beneath the pulpit of Sant'Ambrogio basilica in Milan, Italy, in the same spot where it was originally placed (which makes it the only original part of the paleochristian original basilica still in place).

Gallery

Footnotes

- ↑ sarcophagus. (n.d.). The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Retrieved September 12, 2007, from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/sarcophagus

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History ed by Iorwerth Eiddon et al. 2nd ed. Vol. II pt.2, Cambridge University Press, 1975. ISBN 0521086914 Google Books, p 521.

- ↑ Beruit National Museum ["The Sarcophagus of King Ahiram"] Retrieved September 12, 2007

- ↑ (2004)Kozlowski, Jamie. ["Obsession With Death"] Retrieved September 12, 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. 2004. The Sarcophagus of Anchnesraneferab Queen of Ahmes II King of Egypt. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1417947608

- Grajetzki, Wolfram. 2003. Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt: Life in Death for Rich and Poor. Duckworth Publishers. ISBN 0715632175

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.