Difference between revisions of "Saint Margaret of Scotland" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) m |

|||

| (16 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | {| | + | {{Infobox Saint |

| − | + | |name=Saint Margaret of Scotland | |

| − | | | + | |birth_date= c. 1046 |

| − | | | + | |death_date= November 16, 1093 |

| − | + | |feast_day= November 16 / June 10. June 16 in Scotland. | |

| − | | | + | |venerated_in=[[Roman Catholic Church]], [[Anglican Communion|Anglican Church]] |

| − | + | |image= StMargareth edinburgh castle2.jpg | |

| − | + | |imagesize=175px | |

| − | + | |caption=Stained glass image of Saint Margaret of Scotland in the small chapel at Edinburgh Castle. | |

| − | | | + | |birth_place= Castle Reka, Southern [[Hungary]] |

| − | + | |death_place=Edinburgh Castle, Midlothian, [[Scotland]] | |

| − | + | |titles=Queen and Saint | |

| − | | | + | |beatified_date= |

| − | | | + | |beatified_place= |

| − | | | + | |beatified_by= |

| − | | | + | |canonized_date=1250 |

| − | | | + | |canonized_place= |

| − | | | + | |canonized_by=Pope Innocent IV |

| − | | | + | |attributes= |

| − | | | + | |patronage=death of children; large families; learning; queens; Scotland; widows; Dunfermline; Anglo-Scottish relations |

| − | | | + | |major_shrine=Dunfermline Abbey (Fife, [[Scotland]]), now destroyed, footings survive; Surviving relics were sent to the [[Escorial]], near [[Madrid]], [[Spain]], but have since been lost. |

| − | | | + | |suppressed_date= |

| − | | | + | |issues= |

| − | + | }} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | '''Saint Margaret''' (c. | + | '''Saint Margaret''' (c. 1046 – November 16, 1093), was the sister of Edgar Ætheling, the [[Anglo-Saxons|Anglo-Saxon]] heir to the throne of [[England]]. She married Malcolm III, King of Scots, becoming his queen consort in 1070. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Her influence, which stemmed from a lifelong dedication to personal piety, was essential to the revivification of [[Roman Catholicism]] in [[Scotland]], a fact that led to her [[canonization]] in 1250. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Biography== | ||

| − | + | The daughter of the English Prince [[Edward the Exile]] and granddaughter of [[Edmund II of England|Edmund Ironside]], Margaret was born and raised in [[Hungary]], a country that had welcomed the deposed royal family (Farmer, 1997). Though her family returned to Britain after the power of its Danish overlords waned, the young princess (and her surviving relatives) were soon forced to flee again—this time by the death of her father (1057 C.E.) and the Norman conquest of England (1066 C.E.). Arriving in Scotland, Margaret and her mother (Agatha) sought amnesty in the court of [[Malcolm III of Scotland|Malcolm III]], a request that he granted graciously (Butler, 1956; Farmer, 1997). According to Turgot (Margaret's hagiographer), the young noblewoman's penchant for personal piety was already well-established by this time: | |

| − | The daughter of the English | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>Whilst Margaret was yet in the flower of youth, she began to lead a very strict life, to love God above all things, to employ herself in the study of the Divine writings, and therein with joy to exercise her mind. Her understanding was keen to comprehend any matter, whatever it might be; to this was joined a great tenacity of memory, enabling her to store it up, along with a graceful flow of language to express it (Turgot, 1896).</blockquote> | |

| + | |||

| + | King Malcolm, who had been widowed while still relatively young, was both personally and politically attracted to the possibility of marrying Margaret (as she was both a beautiful woman and one of the few remaining members of the Anglo-Saxon royal family). Though she demurred initially, the two were eventually wed (ca. 1070 C.E.). Their married bliss, captured in various histories and hagiographies of the era, proved to be a turning point in the political and religious culture of Scotland. Seeking to rectify the [[Roman Catholicism]] of her adopted homeland, the young queen convened several synods, each aimed to address various practical issues—from the "practice of Easter communion" to the "abstinence from servile works on Sundays" (Farmer, 1997). Butler also notes that "many scandalous practices, such as simony, usury, and incestuous marriages, were strictly prohibited." Her procedural interest in the church was echoed in her personal devotional practice, wherein she spent the majority of her hours in prayer and austerity (Huddleston, 1910; Farmer, 1997). | ||

| + | |||

| + | King Malcolm could not help but be influenced by his wife's piety, a fact that eventually led to his equal participation in many of her "faith-based" initiatives, as described in her hagiography: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>By the help of God, [Margaret] made him most attentive to the works of justice, mercy, almsgiving, and other virtues. From her he learnt how to keep the vigils of the night in constant prayer; she instructed him by her exhortation and example how to pray to God with groanings from the heart and abundance of tears. I was astonished, I confess, at this great miracle of God's mercy when I perceived in the king such a steady earnestness in his devotion, and I wondered how it was that there could exist in the heart of a man living in the world such, an entire sorrow for sin. There was in him a sort of dread of offending one whose life was so venerable; for he could not but perceive from her conduct that Christ dwelt within her; nay, more, he readily obeyed her wishes and prudent counsels in all things. Whatever she refused, he refused also, whatever pleased her, he also loved for the love of her. Hence it was that, although he could not read, he would turn over and examine books which she used either for her devotions or her study; and whenever he heard her express especial liking for a particular book, he also would look at it with special interest, kissing it, and often taking it into his hands (Turgot, 1896).</blockquote> | ||

| + | With the patronage of two such rulers, Scottish Catholicism experienced a tremendous renewal, as the royal couple endeavored to spread Christianity through the construction and renovation of churches and monasteries, including the commissioning of Dunfermline Abbey and the rebuilding of the Abbey of Iona (founded by [[Saint Columba]]) (Farmer, 1997) | ||

| + | |||

| + | As Butler notes, however, the queen's most notable characteristic was her devotion to the poor and downtrodden: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>She often visited the sick and tended them with her own hands. She erected hostels for strangers and ransomed many captives—preferably those of English nationality. When she appeared outside in public, she was invariably surrounded by beggars, none of whom went away unrelieved, and she never sat down at table without first having fed nine little orphans and twenty-four adults. Often—especially during Advent and Lent—the king and queen would entertain three hundred poor persons, serving them on their knees with dishes similar to those provided for their own table (Butler, 1956).</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Their years of joyful and pious matrimony came to an abrupt end in 1093, when her husband and their eldest son, Edward, were killed in siege against the English at Alnwick Castle. Already ill, Margaret's constitution was unable to bear this incalculable loss. She died on November 16, 1093, three days after the deaths of her husband and eldest son (Farmer, 1997; Butler, 1956). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Progeny=== | ||

| − | |||

Margaret and Malcolm had eight children, six sons and two daughters: | Margaret and Malcolm had eight children, six sons and two daughters: | ||

| − | + | * Edward, killed 1093. | |

| − | + | * [[Edmund of Scotland]]. | |

| − | + | * [[Ethelred of Scotland]], abbot of Dunkeld. | |

| − | + | * [[King Edgar of Scotland]]. | |

| − | + | * [[King Alexander I of Scotland]]. | |

| − | + | * [[King David I of Scotland]]. | |

| − | + | * [[Matilda of England|Edith of Scotland]], also called Matilda, married King Henry I of England. | |

| − | + | * Mary of Scotland, married Eustace III of Boulogne. | |

| + | |||

| + | ==Legacy and Veneration== | ||

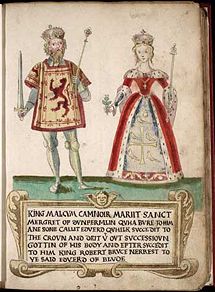

| − | + | [[Image:Malcum Camnoir.jpg|thumb|right|215px|Malcolm and Margaret as depicted in a sixteenth century armorial]] | |

| + | Margaret was [[canonization|canonized]] in 1250 by [[Pope Innocent IV]] on account of her personal holiness and fidelity to the Church. Several centuries later (in 1673), she was also named the patron saint of Scotland. Her relics were initially interred in Dunfermline Abbey, but were transferred to a monastery in Madrid during the Reformation (Farmer, 1997). | ||

| − | + | The [[Roman Catholic]] Church formerly marked the feast of Saint Margaret of Scotland on June 10, but the date was transferred to November 16, the actual day of her death, in the [[liturgical]] reform of 1972. Queen Margaret University (founded in 1875), Queen Margaret Hospital (just outside Dunfermline), North Queensferry, South Queensferry and several streets in Dunfermline are all named after her. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Though widely revered, it should be noted that the legacy of Queen Margaret is not entirely laudatory. Specifically, some Scottish nationalists blame her for the introduction of English habits into Scottish religious and political life, and for precipitating the decline of Gaelic culture. As a result, in Gaeldom, she has usually not been considered a [[saint]], but is instead referred to as ''Mairead/Maighread nam Mallachd:'' “Accursed Margaret” (Best, 1999; Farmer, 1997). | |

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | |||

| − | + | <references /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ''Some elements included from the 1911 version of ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', a text now in the public domain.'' | |

| − | *[ | + | |

| + | * Best, Nicholas. ''The Kings and Queens of Scotland.'' London: Sterling. 1999. ISBN 0-297-82489-9 | ||

| + | * Butler, Alban. ''Lives of the Saints.'' Palm Publishers, 1956. | ||

| + | * Farmer, David Hugh. ''The Oxford Dictionary of Saints.'' Oxford University Press. 1997. ISBN 0192800582 | ||

| + | * Huddleston, G. Roger. [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09655c.htm St. Margaret of Scotland.] Retrieved October 22, 2007. | ||

| + | * Parsons, John Carmi, and Wheeler, Bonnie. ''Medieval Mothering.'' New York: Taylor and Francis. 1996. ISBN 0815336659 | ||

| + | * Turgot, Bishop Of Saint Andrews. ''The Life Of St Margaret, Queen Of Scotland.'' Edinburgh: David Douglas. 1896. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{start box}} |

| − | + | {{s-bef|rows=1|before=Ingibiorg Finnsdottir}} | |

| − | + | {{s-ttl|title=Queen consort of Scotland|years=1070–1093}} | |

| − | + | {{s-aft|rows=1|after=Sybilla de Normandy}} | |

| − | + | {{end box}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | + | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] |

| − | [[Category:Religion]] | + | [[Category: Religion]] |

| − | [[Category:Biography]] | + | [[Category: Biography]] |

{{credit|157866025}} | {{credit|157866025}} | ||

Latest revision as of 13:25, 5 September 2022

| Saint Margaret of Scotland | |

|---|---|

Stained glass image of Saint Margaret of Scotland in the small chapel at Edinburgh Castle. | |

| Queen and Saint | |

| Born | c. 1046 in Castle Reka, Southern Hungary |

| Died | November 16, 1093 in Edinburgh Castle, Midlothian, Scotland |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Church |

| Canonized | 1250

by Pope Innocent IV |

| Major shrine | Dunfermline Abbey (Fife, Scotland), now destroyed, footings survive; Surviving relics were sent to the Escorial, near Madrid, Spain, but have since been lost. |

| Feast | November 16 / June 10. June 16 in Scotland. |

| Patronage | death of children; large families; learning; queens; Scotland; widows; Dunfermline; Anglo-Scottish relations |

Saint Margaret (c. 1046 – November 16, 1093), was the sister of Edgar Ætheling, the Anglo-Saxon heir to the throne of England. She married Malcolm III, King of Scots, becoming his queen consort in 1070.

Her influence, which stemmed from a lifelong dedication to personal piety, was essential to the revivification of Roman Catholicism in Scotland, a fact that led to her canonization in 1250.

Biography

The daughter of the English Prince Edward the Exile and granddaughter of Edmund Ironside, Margaret was born and raised in Hungary, a country that had welcomed the deposed royal family (Farmer, 1997). Though her family returned to Britain after the power of its Danish overlords waned, the young princess (and her surviving relatives) were soon forced to flee again—this time by the death of her father (1057 C.E.) and the Norman conquest of England (1066 C.E.). Arriving in Scotland, Margaret and her mother (Agatha) sought amnesty in the court of Malcolm III, a request that he granted graciously (Butler, 1956; Farmer, 1997). According to Turgot (Margaret's hagiographer), the young noblewoman's penchant for personal piety was already well-established by this time:

Whilst Margaret was yet in the flower of youth, she began to lead a very strict life, to love God above all things, to employ herself in the study of the Divine writings, and therein with joy to exercise her mind. Her understanding was keen to comprehend any matter, whatever it might be; to this was joined a great tenacity of memory, enabling her to store it up, along with a graceful flow of language to express it (Turgot, 1896).

King Malcolm, who had been widowed while still relatively young, was both personally and politically attracted to the possibility of marrying Margaret (as she was both a beautiful woman and one of the few remaining members of the Anglo-Saxon royal family). Though she demurred initially, the two were eventually wed (ca. 1070 C.E.). Their married bliss, captured in various histories and hagiographies of the era, proved to be a turning point in the political and religious culture of Scotland. Seeking to rectify the Roman Catholicism of her adopted homeland, the young queen convened several synods, each aimed to address various practical issues—from the "practice of Easter communion" to the "abstinence from servile works on Sundays" (Farmer, 1997). Butler also notes that "many scandalous practices, such as simony, usury, and incestuous marriages, were strictly prohibited." Her procedural interest in the church was echoed in her personal devotional practice, wherein she spent the majority of her hours in prayer and austerity (Huddleston, 1910; Farmer, 1997).

King Malcolm could not help but be influenced by his wife's piety, a fact that eventually led to his equal participation in many of her "faith-based" initiatives, as described in her hagiography:

By the help of God, [Margaret] made him most attentive to the works of justice, mercy, almsgiving, and other virtues. From her he learnt how to keep the vigils of the night in constant prayer; she instructed him by her exhortation and example how to pray to God with groanings from the heart and abundance of tears. I was astonished, I confess, at this great miracle of God's mercy when I perceived in the king such a steady earnestness in his devotion, and I wondered how it was that there could exist in the heart of a man living in the world such, an entire sorrow for sin. There was in him a sort of dread of offending one whose life was so venerable; for he could not but perceive from her conduct that Christ dwelt within her; nay, more, he readily obeyed her wishes and prudent counsels in all things. Whatever she refused, he refused also, whatever pleased her, he also loved for the love of her. Hence it was that, although he could not read, he would turn over and examine books which she used either for her devotions or her study; and whenever he heard her express especial liking for a particular book, he also would look at it with special interest, kissing it, and often taking it into his hands (Turgot, 1896).

With the patronage of two such rulers, Scottish Catholicism experienced a tremendous renewal, as the royal couple endeavored to spread Christianity through the construction and renovation of churches and monasteries, including the commissioning of Dunfermline Abbey and the rebuilding of the Abbey of Iona (founded by Saint Columba) (Farmer, 1997)

As Butler notes, however, the queen's most notable characteristic was her devotion to the poor and downtrodden:

She often visited the sick and tended them with her own hands. She erected hostels for strangers and ransomed many captives—preferably those of English nationality. When she appeared outside in public, she was invariably surrounded by beggars, none of whom went away unrelieved, and she never sat down at table without first having fed nine little orphans and twenty-four adults. Often—especially during Advent and Lent—the king and queen would entertain three hundred poor persons, serving them on their knees with dishes similar to those provided for their own table (Butler, 1956).

Their years of joyful and pious matrimony came to an abrupt end in 1093, when her husband and their eldest son, Edward, were killed in siege against the English at Alnwick Castle. Already ill, Margaret's constitution was unable to bear this incalculable loss. She died on November 16, 1093, three days after the deaths of her husband and eldest son (Farmer, 1997; Butler, 1956).

Progeny

Margaret and Malcolm had eight children, six sons and two daughters:

- Edward, killed 1093.

- Edmund of Scotland.

- Ethelred of Scotland, abbot of Dunkeld.

- King Edgar of Scotland.

- King Alexander I of Scotland.

- King David I of Scotland.

- Edith of Scotland, also called Matilda, married King Henry I of England.

- Mary of Scotland, married Eustace III of Boulogne.

Legacy and Veneration

Margaret was canonized in 1250 by Pope Innocent IV on account of her personal holiness and fidelity to the Church. Several centuries later (in 1673), she was also named the patron saint of Scotland. Her relics were initially interred in Dunfermline Abbey, but were transferred to a monastery in Madrid during the Reformation (Farmer, 1997).

The Roman Catholic Church formerly marked the feast of Saint Margaret of Scotland on June 10, but the date was transferred to November 16, the actual day of her death, in the liturgical reform of 1972. Queen Margaret University (founded in 1875), Queen Margaret Hospital (just outside Dunfermline), North Queensferry, South Queensferry and several streets in Dunfermline are all named after her.

Though widely revered, it should be noted that the legacy of Queen Margaret is not entirely laudatory. Specifically, some Scottish nationalists blame her for the introduction of English habits into Scottish religious and political life, and for precipitating the decline of Gaelic culture. As a result, in Gaeldom, she has usually not been considered a saint, but is instead referred to as Mairead/Maighread nam Mallachd: “Accursed Margaret” (Best, 1999; Farmer, 1997).

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Some elements included from the 1911 version of Encyclopædia Britannica, a text now in the public domain.

- Best, Nicholas. The Kings and Queens of Scotland. London: Sterling. 1999. ISBN 0-297-82489-9

- Butler, Alban. Lives of the Saints. Palm Publishers, 1956.

- Farmer, David Hugh. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford University Press. 1997. ISBN 0192800582

- Huddleston, G. Roger. St. Margaret of Scotland. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- Parsons, John Carmi, and Wheeler, Bonnie. Medieval Mothering. New York: Taylor and Francis. 1996. ISBN 0815336659

- Turgot, Bishop Of Saint Andrews. The Life Of St Margaret, Queen Of Scotland. Edinburgh: David Douglas. 1896.

| Preceded by: Ingibiorg Finnsdottir |

Queen consort of Scotland 1070–1093 |

Succeeded by: Sybilla de Normandy |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.