Difference between revisions of "Roman trade with India" - New World Encyclopedia

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) (images OK) |

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

[[Image:Diadochen1.png|thumb|right|float|500px|The Seleucid and the Ptolemaic dynasties controlled trade networks to India before the establishment of Roman Egypt. | [[Image:Diadochen1.png|thumb|right|float|500px|The Seleucid and the Ptolemaic dynasties controlled trade networks to India before the establishment of Roman Egypt. | ||

{{legend|#787CAD|Kingdom of [[Ptolemy I Soter|Ptolemy]]}}{{legend|#C3B933|Kingdom of [[Seleucus]]}}]] | {{legend|#787CAD|Kingdom of [[Ptolemy I Soter|Ptolemy]]}}{{legend|#C3B933|Kingdom of [[Seleucus]]}}]] | ||

| − | The [[Seleucid dynasty]] controlled a developed network of trade with India which had previously existed under the influence of the [[Persian]] [[Achaemenid dynasty]].<ref name=Potter1>Potter 2004: 20</ref> The Greek Ptolemaic dynasty, controlling the western and northern end of other trade routes to [[Arabia|Southern Arabia]] and India,<ref name=Potter1/> had begun to exploit trading opportunities with India prior to the Roman involvement but according to the historian [[Strabo]] the volume of commerce between India and Greece | + | The [[Seleucid dynasty]] controlled a developed network of trade with India which had previously existed under the influence of the [[Persian]] [[Achaemenid dynasty]].<ref name=Potter1>Potter 2004: 20</ref> The Greek Ptolemaic dynasty, controlling the western and northern end of other trade routes to [[Arabia|Southern Arabia]] and India,<ref name=Potter1/> had begun to exploit trading opportunities with India prior to the Roman involvement but according to the historian [[Strabo]] the volume of commerce between India and Greece paled compared to later Indian-Roman trade.<ref name=Young1/> |

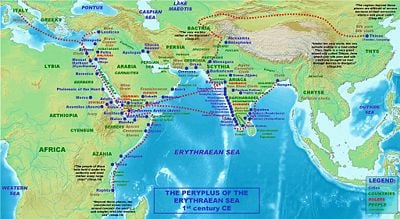

| − | The ''[[Periplus Maris Erythraei]]'' mentions a time when sea trade between India and Egypt | + | The ''[[Periplus Maris Erythraei]]'' mentions a time when sea trade between India and Egypt occurred through indirect sailings.<ref name=Young1>Young 2001: 19</ref> The cargo under those situations shipped to [[Aden]]:<ref name=Young1/> |

<blockquote>Eudaimon Arabia was called fortunate, being once a city, when, because ships neither came from India to [[Egypt]] nor did those from Egypt dare to go further but only came as far as this place, it received the cargoes from both, just as [[Alexandria]] receives goods brought from outside and from Egypt.</blockquote> | <blockquote>Eudaimon Arabia was called fortunate, being once a city, when, because ships neither came from India to [[Egypt]] nor did those from Egypt dare to go further but only came as far as this place, it received the cargoes from both, just as [[Alexandria]] receives goods brought from outside and from Egypt.</blockquote> | ||

| − | The Ptolemaic dynasty had developed trade with India using the Red Sea ports.<ref name=Shaw1>Shaw 2003: 426</ref> With the establishment of Roman Egypt, the Romans took over and further developed the already existing trade using | + | The Ptolemaic dynasty had developed trade with India using the Red Sea ports.<ref name=Shaw1>Shaw 2003: 426</ref> With the establishment of Roman Egypt, the Romans took over and further developed the already existing trade using those ports.<ref name=Shaw1/> |

==Establishment== | ==Establishment== | ||

[[Image:AugustusCoinPudukottaiHoardIndia.jpg|thumb|Coin of the Roman emperor [[Augustus]] found at the [[Pudukottai]] hoard. [[British Museum]].]] | [[Image:AugustusCoinPudukottaiHoardIndia.jpg|thumb|Coin of the Roman emperor [[Augustus]] found at the [[Pudukottai]] hoard. [[British Museum]].]] | ||

| − | The replacement of [[Greece]] by the Roman empire as the administrator of the [[Mediterranean]] basin led to the strengthening of direct maritime trade with the east and the elimination of the taxes extracted previously by the middlemen of various land based trading routes.<ref name=Lach1>Lach 1994: 13</ref> Strabo's mention of the vast increase in trade following the Roman annexation of Egypt indicates that | + | The replacement of [[Greece]] by the Roman empire as the administrator of the [[Mediterranean]] basin led to the strengthening of direct maritime trade with the east and the elimination of the taxes extracted previously by the middlemen of various land based trading routes.<ref name=Lach1>Lach 1994: 13</ref> Strabo's mention of the vast increase in trade following the Roman annexation of Egypt indicates that he knew, and manipulated for trade in his time, the monsoon season .<ref>Young 2001: 20</ref> |

The trade started by [[Eudoxus of Cyzicus]] in 130 B.C.E. kept increasing, and according to Strabo (II.5.12.):<ref name=Strabo1>{{cite web| title = The Geography of Strabo published in Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917|url = http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/2E1*.html| format = HTML}}</ref> | The trade started by [[Eudoxus of Cyzicus]] in 130 B.C.E. kept increasing, and according to Strabo (II.5.12.):<ref name=Strabo1>{{cite web| title = The Geography of Strabo published in Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917|url = http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/2E1*.html| format = HTML}}</ref> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | By the time of Augustus up to 120 ships | + | By the time of Augustus up to 120 ships set sail every year from Myos Hormos to India.<ref name=Strabo1/> Rome used so much gold for that trade, and apparently recycled by the [[Kushan Empire|Kushans]] for their own coinage, that [[Pliny the Elder|Pliny]] (NH VI.101) complained about the drain of specie to India:<ref>"minimaque computatione miliens centena milia sestertium annis omnibus India et Seres et paeninsula illa imperio nostro adimunt: tanti nobis deliciae et feminae constant. quota enim portio ex illis ad deos, quaeso, iam vel ad inferos pertinet?" Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.</ref> |

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

==Ports== | ==Ports== | ||

===Roman Ports=== | ===Roman Ports=== | ||

| − | + | [[Arsinoe]], [[Berenice Troglodytica|Berenice]] and [[Myos Hormos]] constituted the three main Roman ports involved with eastern trade. Arsinoe served as one of the early trading centers but Myos Hormos and Berenice, more easily accessible, soon overshadowed it. | |

====Arsinoe==== | ====Arsinoe==== | ||

[[Image:Egypt-region-map-cities.gif|thumb|260px|right|Sites of Egyptian Red Sea ports, including Alexandria and Berenice.]] | [[Image:Egypt-region-map-cities.gif|thumb|260px|right|Sites of Egyptian Red Sea ports, including Alexandria and Berenice.]] | ||

| − | The Ptolemaic dynasty exploited the strategic position of [[Alexandria]] to secure trade with India.<ref name=Lindsay1>Lindsay 2006: 101</ref> The course of trade with the east then seems to have been first through the harbor of Arsinoe, the present day [[Suez]].<ref name=Lindsay1/> The goods from the [[East African]] trade | + | The Ptolemaic dynasty exploited the strategic position of [[Alexandria]] to secure trade with India.<ref name=Lindsay1>Lindsay 2006: 101</ref> The course of trade with the east then seems to have been first through the harbor of Arsinoe, the present day [[Suez]].<ref name=Lindsay1/> The goods from the [[East African]] trade landed at one of the three main Roman ports, [[Arsinoe]], Berenice or Myos Hormos.<ref>O'Leary 2001: 72</ref> The Romans cleared out the canal from the Nile to harbor center of Arsinoe on the Red Sea, which had silted up.<ref name=Fayle1>Fayle 2006: 52</ref> That represented one of the many efforts the Roman administration had to undertake to divert as much of the trade to the maritime routes as possible.<ref name=Fayle1/> |

| − | + | The rising prominence of Myos Hermos eventually overshadowed Arsinoe.<ref name=Fayle1/> The navigation to the northern ports, such as Arsinoe-Clysma, became difficult in comparison to Myos Hermos due to the northern winds in the [[Gulf of Suez]].<ref name=Freeman1>Freeman 2003: 72</ref> Venturing to those northern ports presented additional difficulties such as [[shoals]], [[reef]]s and treacherous [[Ocean current|currents]].<ref name=Freeman1/> | |

====Myos Hormos and Berenice==== | ====Myos Hormos and Berenice==== | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

Myos Hormos and Berenice appear to have been important ancient trading ports, possibly used by the [[Pharaonic]] traders of ancient Egypt and the Ptolemaic dynasty before falling into Roman control.<ref name=Shaw1/> | Myos Hormos and Berenice appear to have been important ancient trading ports, possibly used by the [[Pharaonic]] traders of ancient Egypt and the Ptolemaic dynasty before falling into Roman control.<ref name=Shaw1/> | ||

| − | The site of Berenice, since its discovery by Belzoni (1818), has been equated with the ruins near [[Ras Banas]] in Southern Egypt.<ref name=Shaw1/> | + | The site of Berenice, since its discovery by Belzoni (1818), has been equated with the ruins near [[Ras Banas]] in Southern Egypt.<ref name=Shaw1/> The precise location of Myos Hormos has been disputed with the latitude and longitude given in [[Ptolemy]]'s ''[[Geographia (Ptolemy)|Geography]]'' favoring Abu Sha'ar and the accounts given in [[classical literature]] and [[satellite images]] indicating a probable identification with Quesir el-Quadim at the end of a fortified road from [[Koptos]] on the [[Nile]].<ref name=Shaw1/> The Quesir el-Quadim site has further been associated with Myos Hormos following the excavations at el-Zerqa, halfway along the route, which have revealed [[ostraca]] leading to the conclusion that the port at the end of that road may have been Myos Hormos.<ref name=Shaw1/> |

===Indian ports=== | ===Indian ports=== | ||

| − | In India, the ports of [[Barbaricum]] (modern [[Karachi]]), [[Bharuch|Barygaza]], [[Muziris]] and [[Arikamedu]] on the southern tip of India | + | In India, the ports of [[Barbaricum]] (modern [[Karachi]]), [[Bharuch|Barygaza]], [[Muziris]] and [[Arikamedu]] on the southern tip of India acted as the main centers of that trade. The ''Periplus Maris Erythraei'' describes Greco-Roman merchants selling in Barbaricum "thin clothing, figured linens, [[topaz]], [[coral]], [[storax]], [[frankincense]], vessels of glass, silver and gold plate, and a little wine" in exchange for "[[costus]], [[bdellium]], [[boxthorn|lycium]], [[spikenard|nard]], [[turquoise]], [[lapis lazuli]], Seric skins, cotton cloth, [[silk]] yarn, and [[indigo dye|indigo]]".<ref name=Periplus1/> In Barygaza, they would buy wheat, rice, sesame oil, cotton and cloth.<ref name=Periplus1/> |

====Barigaza==== | ====Barigaza==== | ||

| − | Trade with Barigaza, under the control of the [[Indo-Scythian]] [[Western Satrap]] [[Nahapana]] ("Nambanus"), | + | Trade with Barigaza, under the control of the [[Indo-Scythian]] [[Western Satrap]] [[Nahapana]] ("Nambanus"), especially flourished:<ref name=Periplus1>{{cite web| last = Halsall | first = Paul | title = Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century| publisher = Fordham University| url=http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/periplus.html| format = HTML}}</ref> |

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

====Muziris==== | ====Muziris==== | ||

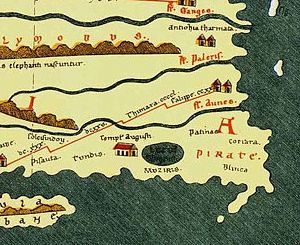

[[Image:TabulaPeutingerianaMuziris.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Muziris, as shown in the in the [[Tabula Peutingeriana]].]] | [[Image:TabulaPeutingerianaMuziris.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Muziris, as shown in the in the [[Tabula Peutingeriana]].]] | ||

| − | [[Muziris]] | + | [[Muziris]] represents a lost port city in the [[South Indian]] state of [[Kerala]] that had been a major center of trade with the Roman Empire.<ref name=BBC1>{{cite news | title = Search for India's ancient city| publisher = BBC| url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4970452.stm}}</ref> Large hoards of coins and innumerable shards of [[amphora]]e found in the town of [[Pattanam]] have elicited recent archaeological interest in finding a probable location of this port city.<ref name=BBC1/> |

According to the Periplus, numerous Greek seamen managed an intense trade with Muziris:<ref name=Periplus1/> | According to the Periplus, numerous Greek seamen managed an intense trade with Muziris:<ref name=Periplus1/> | ||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | [[Pliny the Elder]] also matter-of-factly commented on the qualities of Muziris, although in | + | [[Pliny the Elder]] also matter-of-factly commented on the qualities of Muziris, although in unfavorable terms:<ref>Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturae 6.26</ref> |

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

"If the wind, called Hippalus, happens to be blowing, it is possible to arrive in forty days at the nearest market of India, called Muziris. This, however, is not a particularly desirable place to disembark, on account of the pirates which frequent its vicinity, where they occupy a place called Nitrias; nor, in fact, is it very rich in products. Besides, the road-stead for shipping is a considerable distance from the shore, and the cargoes have to be conveyed in boats, either for loading or discharging." - <small>Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturae 6.26</small> | "If the wind, called Hippalus, happens to be blowing, it is possible to arrive in forty days at the nearest market of India, called Muziris. This, however, is not a particularly desirable place to disembark, on account of the pirates which frequent its vicinity, where they occupy a place called Nitrias; nor, in fact, is it very rich in products. Besides, the road-stead for shipping is a considerable distance from the shore, and the cargoes have to be conveyed in boats, either for loading or discharging." - <small>Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturae 6.26</small> | ||

| − | </blockquote> | + | </blockquote> Settlers from the Rome continued to live in India long after the decline in bilateral trade.[3] Large hoards of Roman coins have been found throughout India, and especially in the busy maritime trading centers of the south.[3] The South Indian kings reissued Roman coinage in their own name after defacing the coins to signify their sovereignty.[19] The Tamil Sangam literature of India records mentions of the traders.[19] One such mention reads: "The beautifully built ships of the Yavanas came with gold and returned with pepper, and Muziris resounded with the noise."[19] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Arikamedu==== | ====Arikamedu==== | ||

| − | The ''Periplus Maris Erythraei'' mentions a marketplace named Poduke (ch. 60), which G.W.B. Huntingford identified as possibly being [[Arikamedu]] (now part of [[Ariyankuppam]]), about 2 miles from the modern [[Pondicherry]].<ref name=Huntingford1>Huntingford 1980: 119.</ref> Huntingford further notes that Roman pottery | + | The ''Periplus Maris Erythraei'' mentions a marketplace named Poduke (ch. 60), which G.W.B. Huntingford identified as possibly being [[Arikamedu]] (now part of [[Ariyankuppam]]), about 2 miles from the modern [[Pondicherry]].<ref name=Huntingford1>Huntingford 1980: 119.</ref> Huntingford further notes that Roman pottery had been found at Arikamedu in 1937, and [[archeology|archeological]] excavations between 1944 and 1949 showed that the city served as "a trading station to which goods of Roman manufacture were imported during the first half of the 1st century AD".<ref name=Huntingford1/> |

==Cultural exchanges== | ==Cultural exchanges== | ||

[[Image:AugustusIndianImitation1stCenturyCE.jpg|thumb|A 1st century CE Indian imitation of a coin of Augustus, [[British Museum]].]] | [[Image:AugustusIndianImitation1stCenturyCE.jpg|thumb|A 1st century CE Indian imitation of a coin of Augustus, [[British Museum]].]] | ||

| − | The Rome-India trade also saw several cultural exchanges which had lasting effect for both the civilizations and others involved in the trade. The [[Ethiopia|Ethiopian]] kingdom of [[Aksum]] | + | The Rome-India trade also saw several cultural exchanges which had lasting effect for both the civilizations and others involved in the trade. The [[Ethiopia|Ethiopian]] kingdom of [[Aksum]] engaged in the [[Indian Ocean]] trade network, receiving an influence by Roman culture and Indian architecture.<ref name=Curtin1/> Traces of Indian influences appear in Roman works of silver and ivory, or in Egyptian cotton and silk fabrics used for sale in [[Europe]].<ref name=Lach2>Lach 1994: 18</ref> The Indian presence in Alexandria may have influenced the culture but scant records remain about the manner of that influence.<ref name=Lach2/> [[Clement of Alexandria]] mentions the [[Buddha]] in his writings and other [[Indian religion]]s find mentions in other texts of the period.<ref name=Lach2/> |

| − | [[Christian]] and [[Jewish]] settlers from the Rome continued to live in India long after the decline in bilateral trade.<ref name=Curtin1/> Large hoards of Roman coins have been found throughout India, and especially in the busy maritime trading centers of the south.<ref name=Curtin1/> The South Indian kings reissued Roman coinage in their own name after defacing the coins | + | [[Christian]] and [[Jewish]] settlers from the Rome continued to live in India long after the decline in bilateral trade.<ref name=Curtin1/> Large hoards of Roman coins have been found throughout India, and especially in the busy maritime trading centers of the south.<ref name=Curtin1/> The South Indian kings reissued Roman coinage in their own name after defacing the coins to signify their sovereignty.<ref name=Kulke1>Kulke 2004: 108</ref> The [[Tamil language|Tamil]] [[Sangam literature]] of India recorded mention of the traders.<ref name=Kulke1/> One such mention reads: "The beautifully built ships of the [[Yavanas]] came with gold and returned with pepper, and Muziris resounded with the noise."<ref name=Kulke1/> |

==Decline== | ==Decline== | ||

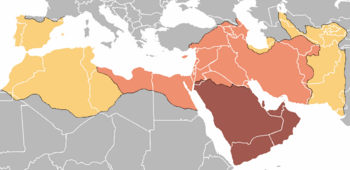

| − | [[Image:Age-of-caliphs.png|thumb|350px|Egypt under the rule of the [[Rashidun]], drawn on the modern state borders. {{legend|#a1584e|Prophet Mohammad, 622-632}} {{legend|#ef9070|Patriarchal Caliphate, 632-661}} {{legend|#fad07d|Umayyad Caliphate, 661-750}}|right]]Following the [[Roman-Persian Wars]] | + | [[Image:Age-of-caliphs.png|thumb|350px|Egypt under the rule of the [[Rashidun]], drawn on the modern state borders. {{legend|#a1584e|Prophet Mohammad, 622-632}} {{legend|#ef9070|Patriarchal Caliphate, 632-661}} {{legend|#fad07d|Umayyad Caliphate, 661-750}}|right]]Following the [[Roman-Persian Wars]] [[Khosrow I]] of the [[Persian]] Sassanian Dynasty captured the areas under the Roman [[Byzantine Empire]].<ref>Farrokh 2007: 252</ref> The Arabs, led by [['Amr ibn al-'As]], crossed into Egypt in late 639 or early 640 C.E.<ref name=Meri1>Meri 2006: 224</ref> That advance marked the beginning of the [[Islamic conquest of Egypt]]<ref name=Meri1/> and the fall of ports such as Alexandria,<ref name=Holl1/> used to secure trade with India by the Greco Roman world since the Ptolemaic dynasty.<ref name=Lindsay1/> |

The decline in trade saw Southern India turn to [[Southeast Asia]] for international trade, where it influenced the native culture to a greater degree than the impressions made on Rome.<ref>Kulke 2004: 106</ref> | The decline in trade saw Southern India turn to [[Southeast Asia]] for international trade, where it influenced the native culture to a greater degree than the impressions made on Rome.<ref>Kulke 2004: 106</ref> | ||

| Line 207: | Line 205: | ||

| publisher = Hakluyt Society | | publisher = Hakluyt Society | ||

| date = 1980 | | date = 1980 | ||

| + | | isbn = 9780904180053 | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 246: | Line 245: | ||

<div class="references-small"> | <div class="references-small"> | ||

| − | *[http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/periplus/periplus.html English translation of the Periplus Maris Erythraei (Voyage around the Erythraean Sea)] | + | *[http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/periplus/periplus.html English translation of the Periplus Maris Erythraei (Voyage around the Erythraean Sea)]. Retrieved December 4, 2007. |

| − | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4970452.stm BBC News: Search for India's ancient city] | + | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4970452.stm BBC News: Search for India's ancient city]. Retrieved December 4, 2007. |

| − | *[http://pondicherry.nic.in/open/depts/tourism1/amedu.htm Arikamedu is the ancient International Trade Centre in Ariyankuppam, Pondicherry] | + | *[http://pondicherry.nic.in/open/depts/tourism1/amedu.htm Arikamedu is the ancient International Trade Centre in Ariyankuppam, Pondicherry]. Retrieved December 4, 2007. |

| − | *[http://www.euratlas.com/Atlas/red_sea/berenice_port.html A picture of Berenice today] | + | *[http://www.euratlas.com/Atlas/red_sea/berenice_port.html A picture of Berenice today]. Retrieved December 4, 2007. |

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 16:38, 4 December 2007

Roman trade with India started around the beginning of the Common Era (CE) following the reign of Augustus and his conquest of Egypt.[1] The use of monsoon winds, which enabled a voyage safer than a long and dangerous coastal voyage, helped enhance trade between India and Rome.[2] Roman trade diaspora stopped in Southern India, establishing trading settlements which remained long after the fall of the Roman empire[3] and Rome's loss of the Red Sea ports,[4] which had previously been used to secure trade with India by the Greco-Roman world since the time of the Ptolemaic dynasty.[5]

Background

The Seleucid dynasty controlled a developed network of trade with India which had previously existed under the influence of the Persian Achaemenid dynasty.[6] The Greek Ptolemaic dynasty, controlling the western and northern end of other trade routes to Southern Arabia and India,[6] had begun to exploit trading opportunities with India prior to the Roman involvement but according to the historian Strabo the volume of commerce between India and Greece paled compared to later Indian-Roman trade.[2]

The Periplus Maris Erythraei mentions a time when sea trade between India and Egypt occurred through indirect sailings.[2] The cargo under those situations shipped to Aden:[2]

Eudaimon Arabia was called fortunate, being once a city, when, because ships neither came from India to Egypt nor did those from Egypt dare to go further but only came as far as this place, it received the cargoes from both, just as Alexandria receives goods brought from outside and from Egypt.

The Ptolemaic dynasty had developed trade with India using the Red Sea ports.[1] With the establishment of Roman Egypt, the Romans took over and further developed the already existing trade using those ports.[1]

Establishment

The replacement of Greece by the Roman empire as the administrator of the Mediterranean basin led to the strengthening of direct maritime trade with the east and the elimination of the taxes extracted previously by the middlemen of various land based trading routes.[7] Strabo's mention of the vast increase in trade following the Roman annexation of Egypt indicates that he knew, and manipulated for trade in his time, the monsoon season .[8]

The trade started by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 130 B.C.E. kept increasing, and according to Strabo (II.5.12.):[9]

"At any rate, when Gallus was prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended the Nile as far as Syene and the frontiers of Ethiopia, and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to India, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise."

By the time of Augustus up to 120 ships set sail every year from Myos Hormos to India.[9] Rome used so much gold for that trade, and apparently recycled by the Kushans for their own coinage, that Pliny (NH VI.101) complained about the drain of specie to India:[10]

"India, China and the Arabian peninsula take one hundred million sesterces from our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us. For what percentage of these imports is intended for sacrifices to the gods or the spirits of the dead?" - Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.

Ports

Roman Ports

Arsinoe, Berenice and Myos Hormos constituted the three main Roman ports involved with eastern trade. Arsinoe served as one of the early trading centers but Myos Hormos and Berenice, more easily accessible, soon overshadowed it.

Arsinoe

The Ptolemaic dynasty exploited the strategic position of Alexandria to secure trade with India.[5] The course of trade with the east then seems to have been first through the harbor of Arsinoe, the present day Suez.[5] The goods from the East African trade landed at one of the three main Roman ports, Arsinoe, Berenice or Myos Hormos.[11] The Romans cleared out the canal from the Nile to harbor center of Arsinoe on the Red Sea, which had silted up.[12] That represented one of the many efforts the Roman administration had to undertake to divert as much of the trade to the maritime routes as possible.[12]

The rising prominence of Myos Hermos eventually overshadowed Arsinoe.[12] The navigation to the northern ports, such as Arsinoe-Clysma, became difficult in comparison to Myos Hermos due to the northern winds in the Gulf of Suez.[13] Venturing to those northern ports presented additional difficulties such as shoals, reefs and treacherous currents.[13]

Myos Hormos and Berenice

Myos Hormos and Berenice appear to have been important ancient trading ports, possibly used by the Pharaonic traders of ancient Egypt and the Ptolemaic dynasty before falling into Roman control.[1]

The site of Berenice, since its discovery by Belzoni (1818), has been equated with the ruins near Ras Banas in Southern Egypt.[1] The precise location of Myos Hormos has been disputed with the latitude and longitude given in Ptolemy's Geography favoring Abu Sha'ar and the accounts given in classical literature and satellite images indicating a probable identification with Quesir el-Quadim at the end of a fortified road from Koptos on the Nile.[1] The Quesir el-Quadim site has further been associated with Myos Hormos following the excavations at el-Zerqa, halfway along the route, which have revealed ostraca leading to the conclusion that the port at the end of that road may have been Myos Hormos.[1]

Indian ports

In India, the ports of Barbaricum (modern Karachi), Barygaza, Muziris and Arikamedu on the southern tip of India acted as the main centers of that trade. The Periplus Maris Erythraei describes Greco-Roman merchants selling in Barbaricum "thin clothing, figured linens, topaz, coral, storax, frankincense, vessels of glass, silver and gold plate, and a little wine" in exchange for "costus, bdellium, lycium, nard, turquoise, lapis lazuli, Seric skins, cotton cloth, silk yarn, and indigo".[14] In Barygaza, they would buy wheat, rice, sesame oil, cotton and cloth.[14]

Barigaza

Trade with Barigaza, under the control of the Indo-Scythian Western Satrap Nahapana ("Nambanus"), especially flourished:[14]

There are imported into this market-town (Barigaza), wine, Italian preferred, also Laodicean and Arabian; copper, tin, and lead; coral and topaz; thin clothing and inferior sorts of all kinds; bright-colored girdles a cubit wide; storax, sweet clover, flint glass, realgar, antimony, gold and silver coin, on which there is a profit when exchanged for the money of the country; and ointment, but not very costly and not much. And for the King there are brought into those places very costly vessels of silver, singing boys, beautiful maidens for the harem, fine wines, thin clothing of the finest weaves, and the choicest ointments. There are exported from these places spikenard, costus, bdellium, ivory, agate and carnelian, lycium, cotton cloth of all kinds, silk cloth, mallow cloth, yarn, long pepper and such other things as are brought here from the various market-towns. Those bound for this market-town from Egypt make the voyage favorably about the month of July, that is Epiphi. - Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, paragraph 49.

Muziris

Muziris represents a lost port city in the South Indian state of Kerala that had been a major center of trade with the Roman Empire.[15] Large hoards of coins and innumerable shards of amphorae found in the town of Pattanam have elicited recent archaeological interest in finding a probable location of this port city.[15]

According to the Periplus, numerous Greek seamen managed an intense trade with Muziris:[14]

"Muziris and Nelcynda, which are now of leading importance (...) Muziris, of the same kingdom, abounds in ships sent there with cargoes from Arabia, and by the Greeks; it is located on a river, distant from Tyndis by river and sea five hundred stadia, and up the river from the shore twenty stadia." - The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, 53-54

Pliny the Elder also matter-of-factly commented on the qualities of Muziris, although in unfavorable terms:[16]

"If the wind, called Hippalus, happens to be blowing, it is possible to arrive in forty days at the nearest market of India, called Muziris. This, however, is not a particularly desirable place to disembark, on account of the pirates which frequent its vicinity, where they occupy a place called Nitrias; nor, in fact, is it very rich in products. Besides, the road-stead for shipping is a considerable distance from the shore, and the cargoes have to be conveyed in boats, either for loading or discharging." - Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturae 6.26

Settlers from the Rome continued to live in India long after the decline in bilateral trade.[3] Large hoards of Roman coins have been found throughout India, and especially in the busy maritime trading centers of the south.[3] The South Indian kings reissued Roman coinage in their own name after defacing the coins to signify their sovereignty.[19] The Tamil Sangam literature of India records mentions of the traders.[19] One such mention reads: "The beautifully built ships of the Yavanas came with gold and returned with pepper, and Muziris resounded with the noise."[19]

Arikamedu

The Periplus Maris Erythraei mentions a marketplace named Poduke (ch. 60), which G.W.B. Huntingford identified as possibly being Arikamedu (now part of Ariyankuppam), about 2 miles from the modern Pondicherry.[17] Huntingford further notes that Roman pottery had been found at Arikamedu in 1937, and archeological excavations between 1944 and 1949 showed that the city served as "a trading station to which goods of Roman manufacture were imported during the first half of the 1st century AD".[17]

Cultural exchanges

The Rome-India trade also saw several cultural exchanges which had lasting effect for both the civilizations and others involved in the trade. The Ethiopian kingdom of Aksum engaged in the Indian Ocean trade network, receiving an influence by Roman culture and Indian architecture.[3] Traces of Indian influences appear in Roman works of silver and ivory, or in Egyptian cotton and silk fabrics used for sale in Europe.[18] The Indian presence in Alexandria may have influenced the culture but scant records remain about the manner of that influence.[18] Clement of Alexandria mentions the Buddha in his writings and other Indian religions find mentions in other texts of the period.[18]

Christian and Jewish settlers from the Rome continued to live in India long after the decline in bilateral trade.[3] Large hoards of Roman coins have been found throughout India, and especially in the busy maritime trading centers of the south.[3] The South Indian kings reissued Roman coinage in their own name after defacing the coins to signify their sovereignty.[19] The Tamil Sangam literature of India recorded mention of the traders.[19] One such mention reads: "The beautifully built ships of the Yavanas came with gold and returned with pepper, and Muziris resounded with the noise."[19]

Decline

Following the Roman-Persian Wars Khosrow I of the Persian Sassanian Dynasty captured the areas under the Roman Byzantine Empire.[20] The Arabs, led by 'Amr ibn al-'As, crossed into Egypt in late 639 or early 640 C.E.[21] That advance marked the beginning of the Islamic conquest of Egypt[21] and the fall of ports such as Alexandria,[4] used to secure trade with India by the Greco Roman world since the Ptolemaic dynasty.[5]

The decline in trade saw Southern India turn to Southeast Asia for international trade, where it influenced the native culture to a greater degree than the impressions made on Rome.[22]

The Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople in the 15th century, marking the beginning of Turkish control over the most direct trade routes between Europe and Asia.[23]

See also

- Indian maritime history

- Buddhism and the Roman world

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Shaw 2003: 426

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Young 2001: 19

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Curtin 1984: 100

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Holl 2003: 9

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Lindsay 2006: 101

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Potter 2004: 20

- ↑ Lach 1994: 13

- ↑ Young 2001: 20

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 The Geography of Strabo published in Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917 (HTML).

- ↑ "minimaque computatione miliens centena milia sestertium annis omnibus India et Seres et paeninsula illa imperio nostro adimunt: tanti nobis deliciae et feminae constant. quota enim portio ex illis ad deos, quaeso, iam vel ad inferos pertinet?" Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.

- ↑ O'Leary 2001: 72

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Fayle 2006: 52

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Freeman 2003: 72

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Halsall, Paul. Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century (HTML). Fordham University.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Search for India's ancient city", BBC.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturae 6.26

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Huntingford 1980: 119.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Lach 1994: 18

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Kulke 2004: 108

- ↑ Farrokh 2007: 252

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Meri 2006: 224

- ↑ Kulke 2004: 106

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Americana 1989: 176

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Young, Gary Keith (2001). Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 B.C.E.-AD 305. Routledge. ISBN 0415242193.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192804588.

- Freeman, Donald B. (2003). The Straits of Malacca: Gateway Or Gauntlet?. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 0773525157.

- O'Leary, De Lacy (2001). Arabia Before Muhammad. Routledge. ISBN 0415231884.

- Fayle, Charles Ernest (2006). A Short History of the World's Shipping Industry. Routledge. ISBN 0415286190.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2007). Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1846031087.

- Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 0415966906.

- The Encyclopedia Americana (1989). Grolier. ISBN 0717201201.

- Lindsay, W S (2006). History of Merchant Shipping and Ancient Commerce. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0543942538.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (2003). Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements. Lexington Books. ISBN 0739104071.

- Curtin, Philip DeArmond and el al. (1984). Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521269318.

- Potter, David Stone (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: Ad 180-395. Routledge. ISBN 0415100585.

- Huntingford, G.W.B. (1980). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Hakluyt Society. ISBN 9780904180053.

- Lach, Donald Frederick (1994). Asia in the Making of Europe: The Century of Discovery. Book 1.. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226467317.

- Kulke, Hermann and Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. ISBN 0415329191.

Further reading

- Lionel Casson, The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text With Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-691-04060-5.

- Chami, F. A. 1999. “The Early Iron Age on Mafia island and its relationship with the mainland.” Azania Vol. XXXIV.

- Miller, J. Innes. 1969. The Spice Trade of The Roman Empire: 29 B.C.E. to A.D. 641. Oxford University Press. Special edition for Sandpiper Books. 1998. ISBN 0-19-814264-1.

External links

- English translation of the Periplus Maris Erythraei (Voyage around the Erythraean Sea). Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- BBC News: Search for India's ancient city. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- Arikamedu is the ancient International Trade Centre in Ariyankuppam, Pondicherry. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- A picture of Berenice today. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

| Part of a series on Trade routes |

|---|

| Amber Road | Hærvejen | Incense Route | Kamboja-Dvaravati Route | King's Highway | Roman-India routes | Royal Road | Salt Road | Siberian Route | Silk Road | Spice Route | Tea route | Varangians to the Greeks | Via Maris | Triangular trade | Volga trade route | Trans-Saharan trade | Old Salt Route| Hanseatic League | Grand Trunk Road |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.