Difference between revisions of "Passamaquoddy" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

m (cop ed) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

When the Europeans began forcing the Passamaquoddy from their lands as early as the sixteenth century, they brought with them [[smallpox]] and other [[disease]]s, which ultimately took a very heavy toll on the natives, reducing their numbers from over 20,000 to around 4,000 practically overnight. In 1586, an epidemic of [[typhus]] broke out, devastating the Wabanaki population considerably. | When the Europeans began forcing the Passamaquoddy from their lands as early as the sixteenth century, they brought with them [[smallpox]] and other [[disease]]s, which ultimately took a very heavy toll on the natives, reducing their numbers from over 20,000 to around 4,000 practically overnight. In 1586, an epidemic of [[typhus]] broke out, devastating the Wabanaki population considerably. | ||

| − | This caused the Passamaquoddy to band together with their neighboring Abenakis, Penobscots, Micmacs (95 percent of who were wiped out by typhoid fever), and Masileet tribes, forming the short-lived and formidable [[Wabanaki Confederacy]]. ''Wabanaki'' means "people of the dawn" or "dawnland people," referring to these peoples as the easterners. The name "Wabanaki" itself, however, may be a corruption of the Passamquoddy term ''Wub-bub-nee-hig'', from ''Wub-bub-phun'' meaning the "first light of dawn before the early sunrise."<ref | + | This caused the Passamaquoddy to band together with their neighboring Abenakis, Penobscots, Micmacs (95 percent of who were wiped out by typhoid fever), and Masileet tribes, forming the short-lived and formidable [[Wabanaki Confederacy]]. ''Wabanaki'' means "people of the dawn" or "dawnland people," referring to these peoples as the easterners. The name "Wabanaki" itself, however, may be a corruption of the Passamquoddy term ''Wub-bub-nee-hig'', from ''Wub-bub-phun'' meaning the "first light of dawn before the early sunrise."<ref> Allen J. Sockabasin, ''An Upriver Passamaquoddy'' (Tilbury House Publishers, 2007. ISBN 978-0884482932)</ref> The confederacy was a semi-loose alliance formulated to help keep the European aggressors and conquest-hungry Iroquois at bay. It was officially disbanded in 1862, however five Wabanaki nations still exist, and they remain friends and allies today. |

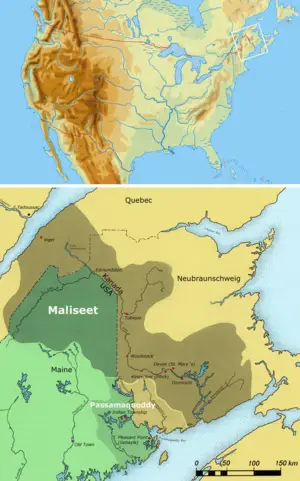

| − | [[Image:Wohngebiet_Maliseet.png|thumb|right|300px|Passamaquoddy Territory]] | + | [[Image:Wohngebiet_Maliseet.png|thumb|right|300px|Passamaquoddy Territory]] The Passamaquoddy Indians were restrained and limited in the United States to the current [[Passamaquoddy Pleasant Point Reservation]]. There are also Passamaquoddy off-reservation trust lands in five Maine counties; these lands total almost four times the size of the reservation proper. They are located in northern and western [[Somerset County, Maine|Somerset County]], northern [[Franklin County, Maine|Franklin County]], northeastern [[Hancock County, Maine|Hancock County]], western Washington County, and several locations in eastern and western [[Penobscot County, Maine|Penobscot County]]. Their total land area is 373.888 km² (144.359 sq mi). There was no resident population on these trust lands as of the 2000 census. The Passamaquoddy also live in [[Charlotte County, New Brunswick]], and maintain active land claims but have no legal status in Canada as a [[First Nation]]. Some Passamaquoddy continue to seek the return of territory now comprised in [[Saint Andrews, New Brunswick]] which they claim as [[Qonasqamkuk]], a Passamaquoddy ancestral capital and burial ground. |

==Culture== | ==Culture== | ||

[[Image:PaulKane-Sketch-Canoe-ROM.jpg|thumb|left|250 px|Sketch of birchbark canoe]] | [[Image:PaulKane-Sketch-Canoe-ROM.jpg|thumb|left|250 px|Sketch of birchbark canoe]] | ||

| − | The Passamaquoddy were a peaceful people, mostly farmers and hunters. They maintained a nomadic existence in the well-watered woods and mountains of the coastal regions along the [[Bay of Fundy]] and [[Gulf of Maine]], and also along the [[ | + | The Passamaquoddy were a peaceful people, mostly farmers and hunters. They maintained a nomadic existence in the well-watered woods and mountains of the coastal regions along the [[Bay of Fundy]] and [[Gulf of Maine]], and also along the [[Saint Croix River]] and its tributaries. They dispersed and hunted inland in the winter; in the summer, they gathered more closely together on the coast and islands and farmed corn, beans, and squash, and harvested seafood, including [[porpoise]]. The name "Passamaquoddy" is an Anglicization of the Passamaquoddy word ''peskotomuhkati,'' the [[prenoun]] form (prenouns being a linguistic feature of Algonquian languages) of ''Peskotomuhkat'' ''(pestəmohkat),'' the name they applied to themselves. Peskotomuhkat literally means "pollock-spearer" or "those of the place where polluck are plentiful,"<ref> [http://www.lib.unb.ca/Texts/Maliseet/dictionary/index.php?command=listAlpha&letter=p Peskotomuhkat] ''Maliseet - Passamaquoddy Dictionary.'' Retrieved November 4, 2007.</ref> reflecting the importance of this fish.<ref>Vincent O. Erickson, 1978. "Maliseet-Passamaquoddy." In ''Northeast,'' ed. Bruce G. Trigger. Vol. 15 of ''Handbook of North American Indians,'' ed. William C. Sturtevant. (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution), 135. Cited in Campbell, Lyle (1997). ''American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America.'' (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 401.</ref> |

| − | Their method of [[fishing]] was spear-fishing rather than angling. They were world-class craftsmen when it came to birch-bark canoes, which provided a lucrative trade industry with other Algonquin tribes. | + | Their method of [[fishing]] was spear-fishing rather than angling. They were world-class craftsmen when it came to birch-bark canoes, which provided a lucrative trade industry with other Algonquin tribes. They also practiced highly decorative forms of basket-weaving, and carpentry, as well as enjoying many colorful forms of jewelry. Their crafts can be found on the Pleasant Point Reservation and in surrounding areas today. |

===Mythology=== | ===Mythology=== | ||

| − | In Passamaquoddy mythology, the main spirit is known as ''Kci Niwesq'' (also spelled Kihci Niweskw, Kichi Niwaskw, and several other ways.) This means "Great Spirit" in the Passamaquoddy language, and is the Passamaquoddy name for the Creator (God | + | In Passamaquoddy mythology, the main spirit is known as ''Kci Niwesq'' (also spelled Kihci Niweskw, Kichi Niwaskw, and several other ways.) This means "Great Spirit" in the Passamaquoddy language, and is the Passamaquoddy name for the Creator (God) who is sometimes also referred to as ''Keluwosit.'' ''Kci Niwesq'' is a divine spirit with no human form or attributes (including gender) and is never personified in Passamaquoddy folklore. The name is pronounced similar to kih-chee nih-wehskw.) |

| − | The "Little People" are known by a variety of names such as the Mikumwesuk, Wunagmeswook and Geow-lud-mo-sis-eg. The Little People of the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy tribes were considered to be dangerous if they are disrespected but are generally benevolent nature spirits. | + | The "Little People" are known by a variety of names such as the Mikumwesuk, Wunagmeswook and Geow-lud-mo-sis-eg. The Little People of the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy tribes were considered to be dangerous if they are disrespected, but are generally benevolent nature spirits. |

One of the infamous animal spirits of the Passamaquoddy was called Loks (rhymes with "blokes" and is also spelled Luks or Lox), and was also known as Wolverine, a malevolent Passamaquoddy deity. He usually demonstrates inappropriate behavior like gluttony, rudeness, and bullying, but in some stories he also plays the role of a dangerous monster. | One of the infamous animal spirits of the Passamaquoddy was called Loks (rhymes with "blokes" and is also spelled Luks or Lox), and was also known as Wolverine, a malevolent Passamaquoddy deity. He usually demonstrates inappropriate behavior like gluttony, rudeness, and bullying, but in some stories he also plays the role of a dangerous monster. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

The Passamaquoddy population in Maine is about 2,500 people, with more than half of adults still speaking the [[Maliseet-Passamaquoddy]] language, shared (other than minor differences in dialect) with the neighboring and related [[Maliseet]] people, and which belongs to the [[Algonquian]] branch of the [[Algic languages|Algic]] language family. | The Passamaquoddy population in Maine is about 2,500 people, with more than half of adults still speaking the [[Maliseet-Passamaquoddy]] language, shared (other than minor differences in dialect) with the neighboring and related [[Maliseet]] people, and which belongs to the [[Algonquian]] branch of the [[Algic languages|Algic]] language family. | ||

| − | To modern Western society, the simple Passamaquoddy subsistence lifestyle of [[hunting]], [[fishing]], [[basketweaving]] and other crafts, storytelling and music may appear impoverished. Yet, to those who grew up in the traditional ways like Allen Sockabasin, preserving the beauty and wisdom of such a lifestyle has become their life's work.<ref name=sockabasin/> | + | To modern Western society, the simple Passamaquoddy subsistence lifestyle of [[hunting]], [[fishing]], [[basketweaving]] and other crafts, storytelling and music may appear impoverished. Yet, to those who grew up in the traditional ways like Allen Sockabasin, preserving the beauty and wisdom of such a lifestyle has become their life's work.<ref> name=sockabasin</ref> |

===Land claims lawsuit === | ===Land claims lawsuit === | ||

Revision as of 23:54, 17 December 2007

The Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati or Pestomuhkati in the Passamaquoddy language) are a Native American/First Nations people who live in northeastern North America, primarily in Maine and New Brunswick. Although closely related peoples sharing a common language, the Maliseet kinsfolk and the Passamaquoddy have always considered themselves politically independent. The French referred to both of these tribes as the "Etchmins." Passamaquoddy Bay, which straddles the United States-Canada border between New Brunswick and Maine, derives its name from the Passamaquoddy people.

History

The Passamaqoddy lacked a written history before the arrival of Europeans but do have an extensive oral tradition.

When the Europeans began forcing the Passamaquoddy from their lands as early as the sixteenth century, they brought with them smallpox and other diseases, which ultimately took a very heavy toll on the natives, reducing their numbers from over 20,000 to around 4,000 practically overnight. In 1586, an epidemic of typhus broke out, devastating the Wabanaki population considerably.

This caused the Passamaquoddy to band together with their neighboring Abenakis, Penobscots, Micmacs (95 percent of who were wiped out by typhoid fever), and Masileet tribes, forming the short-lived and formidable Wabanaki Confederacy. Wabanaki means "people of the dawn" or "dawnland people," referring to these peoples as the easterners. The name "Wabanaki" itself, however, may be a corruption of the Passamquoddy term Wub-bub-nee-hig, from Wub-bub-phun meaning the "first light of dawn before the early sunrise."[1] The confederacy was a semi-loose alliance formulated to help keep the European aggressors and conquest-hungry Iroquois at bay. It was officially disbanded in 1862, however five Wabanaki nations still exist, and they remain friends and allies today.

The Passamaquoddy Indians were restrained and limited in the United States to the current Passamaquoddy Pleasant Point Reservation. There are also Passamaquoddy off-reservation trust lands in five Maine counties; these lands total almost four times the size of the reservation proper. They are located in northern and western Somerset County, northern Franklin County, northeastern Hancock County, western Washington County, and several locations in eastern and western Penobscot County. Their total land area is 373.888 km² (144.359 sq mi). There was no resident population on these trust lands as of the 2000 census. The Passamaquoddy also live in Charlotte County, New Brunswick, and maintain active land claims but have no legal status in Canada as a First Nation. Some Passamaquoddy continue to seek the return of territory now comprised in Saint Andrews, New Brunswick which they claim as Qonasqamkuk, a Passamaquoddy ancestral capital and burial ground.

Culture

The Passamaquoddy were a peaceful people, mostly farmers and hunters. They maintained a nomadic existence in the well-watered woods and mountains of the coastal regions along the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine, and also along the Saint Croix River and its tributaries. They dispersed and hunted inland in the winter; in the summer, they gathered more closely together on the coast and islands and farmed corn, beans, and squash, and harvested seafood, including porpoise. The name "Passamaquoddy" is an Anglicization of the Passamaquoddy word peskotomuhkati, the prenoun form (prenouns being a linguistic feature of Algonquian languages) of Peskotomuhkat (pestəmohkat), the name they applied to themselves. Peskotomuhkat literally means "pollock-spearer" or "those of the place where polluck are plentiful,"[2] reflecting the importance of this fish.[3]

Their method of fishing was spear-fishing rather than angling. They were world-class craftsmen when it came to birch-bark canoes, which provided a lucrative trade industry with other Algonquin tribes. They also practiced highly decorative forms of basket-weaving, and carpentry, as well as enjoying many colorful forms of jewelry. Their crafts can be found on the Pleasant Point Reservation and in surrounding areas today.

Mythology

In Passamaquoddy mythology, the main spirit is known as Kci Niwesq (also spelled Kihci Niweskw, Kichi Niwaskw, and several other ways.) This means "Great Spirit" in the Passamaquoddy language, and is the Passamaquoddy name for the Creator (God) who is sometimes also referred to as Keluwosit. Kci Niwesq is a divine spirit with no human form or attributes (including gender) and is never personified in Passamaquoddy folklore. The name is pronounced similar to kih-chee nih-wehskw.)

The "Little People" are known by a variety of names such as the Mikumwesuk, Wunagmeswook and Geow-lud-mo-sis-eg. The Little People of the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy tribes were considered to be dangerous if they are disrespected, but are generally benevolent nature spirits.

One of the infamous animal spirits of the Passamaquoddy was called Loks (rhymes with "blokes" and is also spelled Luks or Lox), and was also known as Wolverine, a malevolent Passamaquoddy deity. He usually demonstrates inappropriate behavior like gluttony, rudeness, and bullying, but in some stories he also plays the role of a dangerous monster.

Another example of a dark Passamaquoddy spirit is Malsum (also spelled Malsumsa or Malsumis.) This name is sometimes given as belonging to an evil wolf who is the twin brother of Glooskap, the benevolent hero. However, the tale of Malsum is probably not an original Passamaquoddy myth—the character does not appear in older Passamaquoddy texts, "Malsum" is not a Passamaquoddy word, and the wolf is not a malevolent figure in Passamaquoddy folktales. It is likely that Maliseet and Passamaquoddy stories with "Malsum" in them were originally about Loks and that the name Malsum was borrowed back from English anthropology texts about other tribes.

Glooskap (also spelled Glooscap, Koluskap, Gluskabe, Gluskabi, and several other ways) is the benevolent culture hero of the Wabanaki tribes (sometimes referred to as a "transformer" by folklorists.) His name is spelled so many different ways because the Passamaquoddy and the other Wabanaki languages were originally unwritten, so English speakers just spelled it however it sounded to them at the time. The correct Passamaquoddy pronounciation is similar to klue-skopp, but with very soft k and p sounds. Glooskap shares some similarities with other Algonquian heroes such as the Anishinabe Manabozho, Blackfoot Napi, and Cree Wesakechak, and many of the same stories are told in different Algonquian tribes with only the identity of the protagonist differing.

Grandmother Woodchuck (Nuhkomoss Munimqehs) was Glooskap's wise old grandmother, who raised him.

Chenoo or Kewahqu were giant cannibal monsters, similar to the Wendigo of the Cree and other northern tribes. The name "Chenoo" comes from the neighboring Micmac tribe and is pronounced cheh-noo. "Kewahqu" is pronounced similar to keh-wah-kwoo.

Contemporary Passamaquoddy

The Passamaquoddy, along with the neighboring Penobscot Nation, are given special political status in the U.S. state of Maine. Both groups are allowed to send a nonvoting representative to the Maine House of Representatives. Although these representatives cannot vote, they may sponsor any legislation regarding Native American affairs, and may co-sponsor any other legislation. They are also entitled to serve on House committees.

The Passamaquoddy population in Maine is about 2,500 people, with more than half of adults still speaking the Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language, shared (other than minor differences in dialect) with the neighboring and related Maliseet people, and which belongs to the Algonquian branch of the Algic language family.

To modern Western society, the simple Passamaquoddy subsistence lifestyle of hunting, fishing, basketweaving and other crafts, storytelling and music may appear impoverished. Yet, to those who grew up in the traditional ways like Allen Sockabasin, preserving the beauty and wisdom of such a lifestyle has become their life's work.[4]

Land claims lawsuit

The Passamaquoddy may be best known outside the region for Passamaquoddy v. Morton, a 1975 land claims lawsuit in the United States which opened the door to successful land claims negotiations for many eastern tribes, giving federal recognition and millions of dollars to purchase trust lands. The Passamaquoddy tribe were awarded $40 million at the resolution of this case by the Maine Land Claims Act of 1980, signed on March 15, 1980, with a similar sum paid to the Penobscot tribe, in return for relinquishing their rights to 19,500 square miles, for roughly 60% of the State of Maine. Most Penobscot live on a reservation at Indian Island, which is near Old Town.

They invested the money well enough that they quickly increased it to $100 million. Their investing strategy was written up as a case study by Harvard Business School. [5]

Notable Passamaquoddy

Melvin Joseph Francis (August 6, 1945–January 12, 2006) was the governor of the Passamaquoddy Pleasant Point Reservation, one of two reservations in Maine of the Passamaquoddy Indian tribe, from 1980 until 1990 and again since 2002.[6] Born and raised in Pleasant Point he attend local schools. After graduating from Shead High School he earned a journeyman's certificate and specialized in carpentry.[7] He spoke the Passamaquoddy language and was engaged in the preservation of his communities traditions. But alike in the betterment of living conditions for his people as a devoted advocate, peacemaker and lending his professional skills were needed. As governor he strongly supported a proposed LNG terminal on tribal land and legislation allowing an Indian-run racetrack casino in Washington County. Both proposals were not without controversy.[6] Francis died when his car crashed head first into a tanker truck. He had been on his way home from the signing of an agreement with the Venezuelan-owned Citgo Petroleum Corporation at Indian Island providing affordable oil to the Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Mi'kmaq and Maliseet tribes in Maine.[8] The Chief Melvin Francis Memorial Fund was set up in his remembrance to improve the education, health, welfare, safety and lives of tribal members.[9]

Other notable Passamaquoddy people include:

Notes

- ↑ Allen J. Sockabasin, An Upriver Passamaquoddy (Tilbury House Publishers, 2007. ISBN 978-0884482932)

- ↑ Peskotomuhkat Maliseet - Passamaquoddy Dictionary. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ↑ Vincent O. Erickson, 1978. "Maliseet-Passamaquoddy." In Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger. Vol. 15 of Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant. (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution), 135. Cited in Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 401.

- ↑ name=sockabasin

- ↑ Ian Frazier, On the Rez (Picador, 2001, ISBN 978-0312278595) pages 78-79

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Paul Carrier Tribal governor dies in crash Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- ↑ Melvin Joseph Francis Passamaquoddy Tribe at Pleasant Point Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- ↑ Leader dies after signing CITGO agreement Indian Country Today Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- ↑ Chief Melvin Francis Memorial Foundation Passamaquoddy Tribe at Pleasant Point. Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- ↑ Maggie Paul, Passamaquoddy Oyate Online. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ↑ Thanks to the Animals By Allen Sockabasin, Passamaquoddy Storyteller. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fewkes, J. Walter. 2007. Contribution to Passamaquoddy Folk-Lore. Dodo Press. ISBN 978-1406523843

- Sockabasin, Allen J. 2007. An Upriver Passamaquoddy. Tilbury House Publishers. ISBN 978-0884482932

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

External links

All links Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- Passamaquoddy Tribal Government Web Site (Pleasant Point)

- Maliseet-Passamaquoddy online dictionary

- Contribution to Passamaquoddy Folk-Lore, by J. Walter Fewkes, reprinted from the Journal of American Folk-Lore, October-December, 1890, from Project Gutenberg

- Passamaquoddy Origins

- Indian Township Reservation and Passamaquoddy Trust Land, Maine United States Census Bureau

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.