Difference between revisions of "Partition of Bengal (1905)" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The '''Partition of Bengal''' in [[1905]], was made on [[16 October]] by then [[Viceroy of India]], [[George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston|Lord Curzon]]. Due to the high level of political unrest generated by the [[Partition (politics)|partition]], the eastern and western parts of Bengal were reunited in 1911. | The '''Partition of Bengal''' in [[1905]], was made on [[16 October]] by then [[Viceroy of India]], [[George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston|Lord Curzon]]. Due to the high level of political unrest generated by the [[Partition (politics)|partition]], the eastern and western parts of Bengal were reunited in 1911. | ||

| − | the project of geography and history | + | the project of geography and history divide et impera |

==Reason for Partition== | ==Reason for Partition== | ||

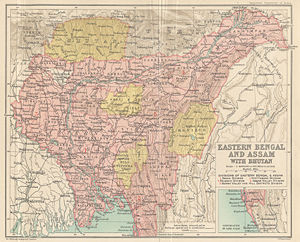

Partitioning Bengal was first considered in [[1903]]. There were also additional proposals to separate [[Chittagong]] and the districts of [[Dhaka]] and [[Mymensingh]] from Bengal and attaching them to the province of Assam. Similarly incorporating [[Chhota Nagpur]] with the central provinces. | Partitioning Bengal was first considered in [[1903]]. There were also additional proposals to separate [[Chittagong]] and the districts of [[Dhaka]] and [[Mymensingh]] from Bengal and attaching them to the province of Assam. Similarly incorporating [[Chhota Nagpur]] with the central provinces. | ||

| − | The government officially published the idea in January [[1904]], and in February, [[George Nathaniel Curzon|Lord Curzon]] made an official tour to eastern districts of Bengal to assess public opinion on the partition. He consulted with leading personalities and delivered speeches at Dhaka, Chittagong and Mymensingh explaining the government's stand on partition. Curzon explained the reason for partition as an administrative improvement; "under the British the province of Bengal was as large as [[France]], with a population of seventy-eight and a half million, nearly as populous as contemporary France and [[Great Britain]] combined." The province included Bihar and Orissa" and the eastern "region was notoriously under-governed." According to Hardy, Curzon did not intend to divide Hindus, who were the majority in the West, from Muslims, the majority in the East but "only Bengalis".<ref>Hardy, page 148.</ref> The plans was to unite the eastern region with Assam (which had been part of Bengal until 1874) to form a "new province with a population of thirty-one millions, of whom 59 percent would be Muslims."<ref>Hardy, page 149.</ref> The plan also involved Bengal | + | The government officially published the idea in January [[1904]], and in February, [[George Nathaniel Curzon|Lord Curzon]] made an official tour to eastern districts of Bengal to assess public opinion on the partition. He consulted with leading personalities and delivered speeches at Dhaka, Chittagong and Mymensingh explaining the government's stand on partition. Curzon explained the reason for partition as an administrative improvement; "under the British the province of Bengal was as large as [[France]], with a population of seventy-eight and a half million, nearly as populous as contemporary France and [[Great Britain]] combined." The province included Bihar and Orissa" and the eastern "region was notoriously under-governed." According to Hardy, Curzon did not intend to divide Hindus, who were the majority in the West, from Muslims, the majority in the East but "only Bengalis".<ref>Hardy, page 148.</ref> The plans was to unite the eastern region with Assam (which had been part of Bengal until 1874) to form a "new province with a population of thirty-one millions, of whom 59 percent would be Muslims."<ref>Hardy, page 149.</ref> The plan also involved Bengal ceding its five Hindi-speaking states to the Central Provinces. It return, it would receive on the western side Sambalpur and five minor Oriya- speaking states from the Central Provinces. Bengal would be left with an area of 141,580 sq. miles and population of 54 million, of which 42 million would be [[Hindu]]s and 9 million [[Muslim]]s. However, Bengali speakers would be a minority in the West "in relation to Biharis and Oriyas"<ref>Hardy, page 149</ref> Administration of the new province would consist of a [[Legislative Council]], a [[Board of Revenue]] of two members, and the jurisdiction of the Calcutta High Court would be left undisturbed. The government pointed out that Eastern Bengal and Assam would have a clearly demarcated western boundary and well defined geographical, ethnological, linguistic and social characteristics. The government of India promulgated their final decision in a resolution dated [[July 19]], 1905 and the partition of Bengal was effected on [[October 16]] of the same year. |

===Reaction to the Plan=== | ===Reaction to the Plan=== | ||

| − | As details of the plan became public knowledge, prominent Bengalis began a series of demonstrations against partition and a boycott of British products. While protest was mainly from Hindus the Muslims nawab of Dhakha was | + | As details of the plan became public knowledge, prominent Bengalis began a series of demonstrations against partition and a boycott of British products. While protest was mainly from Hindus the Muslims nawab of Dhakha was also initially opposed to the plan, even though Dhakha would serve as capital of the new province. Baxter suggests that the "divide and rule" policy was the real reason for partition. Lord Curzon said, "Bengal united is a power; Bengali divided will pull in several different ways."<ref>Baxter, page 39.</ref> Bengalis were the first to benefit from English education in India and as an intellectual class were disproportionately represented in the Civil Service, which was, of course, dominated by colonial officials. They were also in the forefront of calls for greater participation in governance. By splitting Benagli, their influence would be weakened. Bengalis regarded themselves as a nation and did not want to be a linguistic minority in their own province. Indeed, many of those Hindus who were considered "unfriendly if not seditious in character" lived in the east" who dominated "the whole tone of Bengal administration" where under the plan, Muslims would form the majority<ref>Baxter, page 39 citing Sir Andrew Fraser</ref> Calcutta, the capital of the united province, was still at this point also the capital of British India, which meant that Bengalis were at the very center of British power. At the same time, the Muslims of Bengal were considered loyal to the British since they had not joined the [[First War of Indian Independence|anti-British rebellion of 1857-8]], so they would be rewarded. |

| − | the Muslims of Bengal were considered loyal to the British since they had not joined the [[First War of Indian Independence|anti-British rebellion of 1857-8]], so they would be rewarded. | ||

====Partition==== | ====Partition==== | ||

| − | Partition took place October, 1905. It resulted in a huge [[politics|political]] crisis. The Muslims in [[East Bengal]] after initial opposition tended to be much more positive about the arrangement, believing that a separate region would give them more opportunity for education, employment etc. However, partition was especially unpopular by the people of what had become West Bengal, where a huge amount of nationalist literature was created during this period. Opposition by [[Indian National Congress]] was led by [[Sir Henry Cotton]] who had been Chief Commissioner of Assam, but Curzon was not to be moved. Support came from throughout India, where the partition of an historic province was regarded as an act of [[colonialism|colonial]] arrogance and the result of the divide and rule policy.<ref> "Calcutta", says Metcalf, "came alive with rallies, bonfires of foreign goods, petitions, newspapers and posters." Anti-British and pro-self-rule sentiment increased.<ref>Metcalf, page 155.</ref> Later, Cotton, now [[Liberal]] MP for [[Nottingham East]] coordinated the successful campaign to oust the first lieutenant-governor of East Bengal, Sir [[Bampfylde Fuller]]. In 1906, [[Rabindranath Tagore]] wrote [[Amar Shonar Bangla]] as a rallying cry for proponents of annulment of Partition, which, much later, in 1972, became the [[national anthem]] of [[Bangladesh]]. The song "Bande Mataram" which tTgore set to music became the "informal anthem of the nationalist movement after 1905."<ref>Metcalf, page 155</ref> Secret terrorist organizations began to operate, for whom Bengal as their mother-land was epitomized by the goddess [[Kali]], "goddess of power and destruction, to whom they dedicated their weapons."<ref>Metcalf, page 155.</ref> | + | Partition took place October, 1905. It resulted in a huge [[politics|political]] crisis. The Muslims in [[East Bengal]] after initial opposition tended to be much more positive about the arrangement, believing that a separate region would give them more opportunity for education, employment etc. However, partition was especially unpopular by the people of what had become West Bengal, where a huge amount of nationalist literature was created during this period. Opposition by [[Indian National Congress]] was led by [[Sir Henry Cotton]] who had been Chief Commissioner of Assam, but Curzon was not to be moved. His successor, [[Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, 4th Earl of Minto|Lord Minto]] also though it crucial to maintain partition, commenting that it "should and must be maintained since the diminution of Bengali political agitation will assist to remove a serious cause of anxiety ... IT is", he continued, "the growing power of a popul;ation with great intellectual gifts and and a talent for making itself heard which is not unlikely to influence public opinion at home most mischievously."<ref>cited by Edwards, page 87.</ref> Support came from throughout India, where the partition of an historic province was regarded as an act of [[colonialism|colonial]] arrogance and the result of the divide and rule policy.<ref> "Calcutta", says Metcalf, "came alive with rallies, bonfires of foreign goods, petitions, newspapers and posters." Anti-British and pro-self-rule sentiment increased.<ref>Metcalf, page 155.</ref> In fact, the Swadeshi movement emerged from opposition to Partition, which was regarded as "a sinister [[imperialism|imperial]] design to cripple the Bengali led nationalist movement."<ref>Edwards, page 87.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | Later, Cotton, now [[Liberal]] MP for [[Nottingham East]] coordinated the successful campaign to oust the first lieutenant-governor of East Bengal, Sir [[Bampfylde Fuller]]. In 1906, [[Rabindranath Tagore]] wrote [[Amar Shonar Bangla]] as a rallying cry for proponents of annulment of Partition, which, much later, in 1972, became the [[national anthem]] of [[Bangladesh]]. The song "Bande Mataram" which tTgore set to music became the "informal anthem of the nationalist movement after 1905."<ref>Metcalf, page 155</ref> Secret terrorist organizations began to operate, for whom Bengal as their mother-land was epitomized by the goddess [[Kali]], "goddess of power and destruction, to whom they dedicated their weapons."<ref>Metcalf, page 155.</ref> | ||

==Bengal's Partition rescinded== | ==Bengal's Partition rescinded== | ||

| − | Due to these protests, the two parts of Bengal were reunited in 1911. A new partition which divided the province on linguistic, rather than religious, grounds followed, with the Hindi, Oriya and Assamese areas separated to form separate administrative units. The administrative capital of [[British India]] was moved from [[Kolkata|Calcutta]] to [[New Delhi]] as well. | + | [[Image:Curzon hall front.jpg|thumb|Curzon Hall, University of Dhaka.]] Due to these protests, the two parts of Bengal were reunited in 1911. A new partition which divided the province on linguistic, rather than religious, grounds followed, with the Hindi, Oriya and Assamese areas separated to form separate administrative units. The administrative capital of [[British India]] was moved from [[Kolkata|Calcutta]] to [[New Delhi]] as well. |

| + | |||

| + | Dhaka, no longer a capital, was given a University as compensation, founded in 1922. Curzon Hall was handed over to the new foundation as one of its first building. Built in 1904 in preparation for partition, Curzon Hall, which blends Western and [[Moghul Empire|Moghul]] [[architecture|architectural]] styles, was intended to be the Town Hall. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Legacy== | ||

| + | Although protest had been largely Hindu-led and the Muslims of the east were much less unhappy with partition than Hindus were, such eminent leaders of the Indian nationalist movement at [[Nazrul Islam]] and Rabindranath Tagore stressed Hindu-Muslim unity. Although some opponents to partition gave it a [[religion|religious]] aspect by identifying closely with kali, others stressed the unity of the Bengali nation, not religion. Divine and rule, however, continued as a British policy and in 1932 they created different electorates for Muslims, Hindus and other distinctive communities. This encouraged the Muslims to develop as a "social-cultural group" so that even in Bengal where, culturally, Muslims shared much in common with Hindus, they began to regard themselves as a separate nation.<ref>Edwards, page 85.</ref> As Indian nationalism gained momentum, Muslims and Hindus began to demand a new partition, more radical than that of 1905 which would divide Hindu-majority areas from Muslim majority areas to form the independent states of India and [[Pakistan]]. Yet, as as plans for Pakistan were set in motion, many Muslims assumed that the Muslims of Bengal would not want to join the proposed state, partly because of its [[geography|geographical]] distance from the other main center of Muslim majority population but also due to the strength of Bengali nationalism. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The proposed name for the new Muslim state, Pakistan, was formed from '''P'''unjab, '''A'''fghania (North-West Frontier Province), '''K'''ashmir, '''I'''ran , '''S'''indh, '''T'''ukharistan, '''A'''fghanistan, and Balochista'''n''' thus Bengal was not included. The United Bengal Movement did champion a separate, united state for all Bengali on the eve of the [[Partition of Bengal (1947)|1947 partition]] but this failed to attract enough support. This time, it was Hindus were supported partition, largely because after the Communal Award of 1932, Muslims had dominated the Legislature in Bengal, so Hindus now saw their future within India, where Hindus would be a majority. For Hindus, a separate Bengali state was no longer an attractive option. Bengali Muslims, for their part, did not want to live in a United India either. When the Bengali Legislature voted in June 1947, 90 members favored remaining in India and 126 opposed this; 106-35 actually voted against partitioning Bengal but in favor of the whole province joining Pakistan. A vote in the Western region voted 58-21 for partition of Bengal, with the West joining India and the East Pakistan.<ref>[http://banglapedia.net/ht/P_0101.HTM Partition of Bengali, 1947.] Banglapedia. 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2008.</ref> Almost certainly due to the wedge that Britain's divide and rule policy had driven between Hindus and Muslims in Bengali, partition followed more or less on the same lines as that of 1905 except that only the Sylhet region of Assam voted to join (by a majority of 55,578 votes) what was to become East Pakistan. Having religion in common with West Pakistan, however, over a thousand miles away, did not prove strong enough to glue the two provinces of the new nation together. In 1971, after a bloody [[Bangladesh | ||

| − | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 31: | Line 39: | ||

* Baxter, Craig. 1997. ''Bangladesh: from a nation to a state.'' Nations of the modern world. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813328546 | * Baxter, Craig. 1997. ''Bangladesh: from a nation to a state.'' Nations of the modern world. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813328546 | ||

* Bukowski, Jeanie J., and Swarna Rajagopalan. 2000. Re-distribution of authority: a cross-regional perspective. Westport, Conn: Praeger. ISBN 9780275963774 | * Bukowski, Jeanie J., and Swarna Rajagopalan. 2000. Re-distribution of authority: a cross-regional perspective. Westport, Conn: Praeger. ISBN 9780275963774 | ||

| + | * Edwards, Philip. 2004. "''Shakespeare and the confines of art.'' Routledge library editions. London: Routledge. | ||

* Ghosha, Nityapriẏa, and Aśokakumāra Mukhopādhyāẏa. 2005. ''Partition of Bengal: significant | * Ghosha, Nityapriẏa, and Aśokakumāra Mukhopādhyāẏa. 2005. ''Partition of Bengal: significant | ||

signposts, 1905-1911.'' Kolkata: Sahitya Samsad. ISBN 9788179550656 | signposts, 1905-1911.'' Kolkata: Sahitya Samsad. ISBN 9788179550656 | ||

Revision as of 21:38, 13 November 2008

- For the 1947 parition, see 1947 Partition of Bengal

The Partition of Bengal in 1905, was made on 16 October by then Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon. Due to the high level of political unrest generated by the partition, the eastern and western parts of Bengal were reunited in 1911.

the project of geography and history divide et impera

Reason for Partition

Partitioning Bengal was first considered in 1903. There were also additional proposals to separate Chittagong and the districts of Dhaka and Mymensingh from Bengal and attaching them to the province of Assam. Similarly incorporating Chhota Nagpur with the central provinces.

The government officially published the idea in January 1904, and in February, Lord Curzon made an official tour to eastern districts of Bengal to assess public opinion on the partition. He consulted with leading personalities and delivered speeches at Dhaka, Chittagong and Mymensingh explaining the government's stand on partition. Curzon explained the reason for partition as an administrative improvement; "under the British the province of Bengal was as large as France, with a population of seventy-eight and a half million, nearly as populous as contemporary France and Great Britain combined." The province included Bihar and Orissa" and the eastern "region was notoriously under-governed." According to Hardy, Curzon did not intend to divide Hindus, who were the majority in the West, from Muslims, the majority in the East but "only Bengalis".[1] The plans was to unite the eastern region with Assam (which had been part of Bengal until 1874) to form a "new province with a population of thirty-one millions, of whom 59 percent would be Muslims."[2] The plan also involved Bengal ceding its five Hindi-speaking states to the Central Provinces. It return, it would receive on the western side Sambalpur and five minor Oriya- speaking states from the Central Provinces. Bengal would be left with an area of 141,580 sq. miles and population of 54 million, of which 42 million would be Hindus and 9 million Muslims. However, Bengali speakers would be a minority in the West "in relation to Biharis and Oriyas"[3] Administration of the new province would consist of a Legislative Council, a Board of Revenue of two members, and the jurisdiction of the Calcutta High Court would be left undisturbed. The government pointed out that Eastern Bengal and Assam would have a clearly demarcated western boundary and well defined geographical, ethnological, linguistic and social characteristics. The government of India promulgated their final decision in a resolution dated July 19, 1905 and the partition of Bengal was effected on October 16 of the same year.

Reaction to the Plan

As details of the plan became public knowledge, prominent Bengalis began a series of demonstrations against partition and a boycott of British products. While protest was mainly from Hindus the Muslims nawab of Dhakha was also initially opposed to the plan, even though Dhakha would serve as capital of the new province. Baxter suggests that the "divide and rule" policy was the real reason for partition. Lord Curzon said, "Bengal united is a power; Bengali divided will pull in several different ways."[4] Bengalis were the first to benefit from English education in India and as an intellectual class were disproportionately represented in the Civil Service, which was, of course, dominated by colonial officials. They were also in the forefront of calls for greater participation in governance. By splitting Benagli, their influence would be weakened. Bengalis regarded themselves as a nation and did not want to be a linguistic minority in their own province. Indeed, many of those Hindus who were considered "unfriendly if not seditious in character" lived in the east" who dominated "the whole tone of Bengal administration" where under the plan, Muslims would form the majority[5] Calcutta, the capital of the united province, was still at this point also the capital of British India, which meant that Bengalis were at the very center of British power. At the same time, the Muslims of Bengal were considered loyal to the British since they had not joined the anti-British rebellion of 1857-8, so they would be rewarded.

Partition

Partition took place October, 1905. It resulted in a huge political crisis. The Muslims in East Bengal after initial opposition tended to be much more positive about the arrangement, believing that a separate region would give them more opportunity for education, employment etc. However, partition was especially unpopular by the people of what had become West Bengal, where a huge amount of nationalist literature was created during this period. Opposition by Indian National Congress was led by Sir Henry Cotton who had been Chief Commissioner of Assam, but Curzon was not to be moved. His successor, Lord Minto also though it crucial to maintain partition, commenting that it "should and must be maintained since the diminution of Bengali political agitation will assist to remove a serious cause of anxiety ... IT is", he continued, "the growing power of a popul;ation with great intellectual gifts and and a talent for making itself heard which is not unlikely to influence public opinion at home most mischievously."[6] Support came from throughout India, where the partition of an historic province was regarded as an act of colonial arrogance and the result of the divide and rule policy.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag In fact, the Swadeshi movement emerged from opposition to Partition, which was regarded as "a sinister imperial design to cripple the Bengali led nationalist movement."[7]

Later, Cotton, now Liberal MP for Nottingham East coordinated the successful campaign to oust the first lieutenant-governor of East Bengal, Sir Bampfylde Fuller. In 1906, Rabindranath Tagore wrote Amar Shonar Bangla as a rallying cry for proponents of annulment of Partition, which, much later, in 1972, became the national anthem of Bangladesh. The song "Bande Mataram" which tTgore set to music became the "informal anthem of the nationalist movement after 1905."[8] Secret terrorist organizations began to operate, for whom Bengal as their mother-land was epitomized by the goddess Kali, "goddess of power and destruction, to whom they dedicated their weapons."[9]

Bengal's Partition rescinded

Due to these protests, the two parts of Bengal were reunited in 1911. A new partition which divided the province on linguistic, rather than religious, grounds followed, with the Hindi, Oriya and Assamese areas separated to form separate administrative units. The administrative capital of British India was moved from Calcutta to New Delhi as well.

Dhaka, no longer a capital, was given a University as compensation, founded in 1922. Curzon Hall was handed over to the new foundation as one of its first building. Built in 1904 in preparation for partition, Curzon Hall, which blends Western and Moghul architectural styles, was intended to be the Town Hall.

Legacy

Although protest had been largely Hindu-led and the Muslims of the east were much less unhappy with partition than Hindus were, such eminent leaders of the Indian nationalist movement at Nazrul Islam and Rabindranath Tagore stressed Hindu-Muslim unity. Although some opponents to partition gave it a religious aspect by identifying closely with kali, others stressed the unity of the Bengali nation, not religion. Divine and rule, however, continued as a British policy and in 1932 they created different electorates for Muslims, Hindus and other distinctive communities. This encouraged the Muslims to develop as a "social-cultural group" so that even in Bengal where, culturally, Muslims shared much in common with Hindus, they began to regard themselves as a separate nation.[10] As Indian nationalism gained momentum, Muslims and Hindus began to demand a new partition, more radical than that of 1905 which would divide Hindu-majority areas from Muslim majority areas to form the independent states of India and Pakistan. Yet, as as plans for Pakistan were set in motion, many Muslims assumed that the Muslims of Bengal would not want to join the proposed state, partly because of its geographical distance from the other main center of Muslim majority population but also due to the strength of Bengali nationalism.

The proposed name for the new Muslim state, Pakistan, was formed from Punjab, Afghania (North-West Frontier Province), Kashmir, Iran , Sindh, Tukharistan, Afghanistan, and Balochistan thus Bengal was not included. The United Bengal Movement did champion a separate, united state for all Bengali on the eve of the 1947 partition but this failed to attract enough support. This time, it was Hindus were supported partition, largely because after the Communal Award of 1932, Muslims had dominated the Legislature in Bengal, so Hindus now saw their future within India, where Hindus would be a majority. For Hindus, a separate Bengali state was no longer an attractive option. Bengali Muslims, for their part, did not want to live in a United India either. When the Bengali Legislature voted in June 1947, 90 members favored remaining in India and 126 opposed this; 106-35 actually voted against partitioning Bengal but in favor of the whole province joining Pakistan. A vote in the Western region voted 58-21 for partition of Bengal, with the West joining India and the East Pakistan.[11] Almost certainly due to the wedge that Britain's divide and rule policy had driven between Hindus and Muslims in Bengali, partition followed more or less on the same lines as that of 1905 except that only the Sylhet region of Assam voted to join (by a majority of 55,578 votes) what was to become East Pakistan. Having religion in common with West Pakistan, however, over a thousand miles away, did not prove strong enough to glue the two provinces of the new nation together. In 1971, after a bloody [[Bangladesh

See also

- Bangladesh

- West Bengal

- Banglapedia Article on Partition of Bengal

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baxter, Craig. 1997. Bangladesh: from a nation to a state. Nations of the modern world. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813328546

- Bukowski, Jeanie J., and Swarna Rajagopalan. 2000. Re-distribution of authority: a cross-regional perspective. Westport, Conn: Praeger. ISBN 9780275963774

- Edwards, Philip. 2004. "Shakespeare and the confines of art. Routledge library editions. London: Routledge.

- Ghosha, Nityapriẏa, and Aśokakumāra Mukhopādhyāẏa. 2005. Partition of Bengal: significant

signposts, 1905-1911. Kolkata: Sahitya Samsad. ISBN 9788179550656

- Hardy, Peter. 1972. The Muslims of British India. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521084888

- Islam, Sirajul, and Harun-or-Rashid. 1992. History of Bangladesh, 1704-1971. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 9789845123372

- Metcalf, Barbara Daly, and Thomas R. Metcalf. 2002. A concise history of India. Cambridge concise histories. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521630276,

- Saxena, Vinod Kumar. 1987. The Partition of Bengal, 1905-1911: select documents. Delhi: Kanishka Pub. House.

bn:বঙ্গভঙ্গ (১৯০৫) ja:ベンガル分割令 ur:تقسیم بنگال zh:孟加拉分治 (1905年)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Hardy, page 148.

- ↑ Hardy, page 149.

- ↑ Hardy, page 149

- ↑ Baxter, page 39.

- ↑ Baxter, page 39 citing Sir Andrew Fraser

- ↑ cited by Edwards, page 87.

- ↑ Edwards, page 87.

- ↑ Metcalf, page 155

- ↑ Metcalf, page 155.

- ↑ Edwards, page 85.

- ↑ Partition of Bengali, 1947. Banglapedia. 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2008.