Oregon Question

The Oregon boundary dispute (often called the Oregon question) arose as a result of competing British and American claims to the Oregon Country, a region of northwestern North America known also from the British perspective as the Columbia District, a fur-trading division of the Hudson's Bay Company. The region at question lay west of the Continental Divide and between the 42nd Parallel of latitude on the south (the northward limit of New Spain and after 1821 of Mexico) and the 54 degrees, 40 minutes line of latitude (the southward limit of Russian America).

Both the United Kingdom and the United States had territorial and commercial interests in the Oregon country as well as residual claims from treaties with Russia and Spain. By Article III of the Anglo-American Convention of 1818 the United Kingdom and the United States agreed to what has since been described as "joint occupancy", demurring on any resolution of the territorial and treaty issues until a later time. Negotiations over the next few decades failed to settle upon a compromise boundary and the Oregon Dispute became important in geopolitical diplomacy between the British Empire and the new American Republic.

American economic activity in the region until the 1840s consisted of a Boston-owned fur trading post staffed by French Canadians at Fort Astoria near the mouth of the Columbia River, the Whitman Mission east of the Cascades, the Methodist Mission in the Willamette Valley, Fort William on present day Sauvie Island,[1] a saw mill in the valley partly owned by Ewing Young,[2] a grist mill also in the valley built in 1834,[3] the Willamette Cattle Company organized in 1837 to bring over 600 head of cattle to the Willamette Valley, as well as ongoing marine fur trade vessels. The British mandate was in the form of a licence held by the Hudson's Bay Company to trade with the populous aboriginal peoples of the region, and a network of trading posts and routes extended southward from New Caledonia, another HBC fur-trade district, into the Columbia basin. The HBC's headquarters for the entire region became established at Fort Vancouver (today's Vancouver, Washington), which became the centre of a thriving colony of mixed origin, including French Canadians, Hawaiians, Algonkians and Iroquois, as well as the offspring of company employees who had intermarried with various local native populations. Actual American settlers in the region were negligible[citation needed] until the arrival of the Whitman Party in 1843; the Dispute over the region is usually attributed to increasing numbers of American settlers moving into the country, which did not actually take place until the 1840s.

In 1844 the U.S. Democratic Party, appealing to expansionist sentiment, asserted that the U.S. had a valid claim to the entire Oregon Country. Democratic presidential candidate James K. Polk won the 1844 election, but then sought a compromise boundary along the 49th parallel, the same boundary proposed by previous U.S. administrations. Negotiations between the U.S. and the British broke down, however, and tensions grew as American expansionists like U.S. Senator Edward Allen Hannegan of Indiana urged Polk to annex the entire Oregon Country up to latitude 54°40'N, as the Democrats had called for in the election. The turmoil gave rise to slogans like "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!", often mistakenly associated with the 1844 election, and the catchphrase "Manifest Destiny".

The expansionist agenda of Polk and the Democratic Party created the possibility of two different, simultaneous wars, because relations between the United States and Mexico were deteriorating following the annexation of Texas. Just before the outbreak of the war with Mexico, Polk returned to his earlier position on the Oregon boundary and accepted a compromise along the 49th parallel. This agreement was made official in the 1846 Oregon Treaty, and the 49th parallel remains the boundary between the United States and Canada.

Joint occupation

The dispute arose as a result of competing claims between the United States and the United Kingdom to the Oregon Country, which consisted of what is now the Pacific Northwest of the United States and southern British Columbia, Canada. Both nations claimed the region based on earlier exploration and the "right of discovery"; following long European precedent, both sides recognized only limited sovereign rights of the indigenous population.

In 1818, diplomats of the two countries attempted to negotiate a boundary between the rival claims. The Americans suggested dividing the Oregon Country along the 49th parallel, which was the border between the United States and British North America east of the Rocky Mountains. British diplomats wanted a border further south along the Columbia River, so as to maintain the Hudson's Bay Company's control of the lucrative fur trade along that river. As a compromise, the Anglo-American Convention of 1818 (or Treaty of 1818) called for the joint occupation of the region for ten years. As the expiration of the ten-year agreement approached, a second round of negotiations from 1825 to 1827 failed to resolve the issue, and so the joint occupation agreement was renewed, this time with the stipulation that a one-year notice had to be given when either party intended to abrogate the agreement.

Early in the 1840s, negotiations that produced the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty (a border settlement in the east) addressed the Oregon question once again. British negotiators still pressed for the Columbia River boundary, which the Americans would not accept since it would deny the U.S. an easily accessible deep water port on the Pacific Ocean, and so no adjustment to the existing agreement was made. By this time, American settlers were steadily pouring into the region along the Oregon Trail, a development that some observers—both British and American—realized would eventually decide the issue. In 1843, John C. Calhoun famously declared that the U.S. government should pursue a policy of "wise and masterly inactivity" in Oregon, letting settlement determine the eventual boundary. Many of Calhoun's fellow Democrats, however, soon began to advocate a more direct approach.[4]

Election of 1844

| Key figures in the Oregon question | |

|---|---|

| United States | United Kingdom |

| James K. Polk President |

Robert Peel Prime Minister |

| James Buchanan Secretary of State |

Earl of Aberdeen Foreign Secretary |

| Louis McLane Minister to the UK |

Richard Pakenham Minister in Washington |

At the Democratic National Convention before the 1844 U.S. presidential election, the party platform called for the annexation of Texas and asserted that the United States had a "clear and unquestionable" claim to "the whole" of Oregon and "that no portion of the same ought to be ceded to England or any other power." By informally tying the Oregon dispute to the more controversial Texas debate, the Democrats appealed to both Northern expansionists (who were more adamant about the Oregon boundary) and Southern expansionists (who were more focused on annexing Texas). Democratic candidate James K. Polk went on to win a narrow victory over Whig candidate Henry Clay, in part because Clay had taken a stand against expansion. "Fifty-four Forty or Fight!" was not yet coined during this election; one actual Democratic campaign slogan from this election (used in Pennsylvania) was the more mundane "Polk, Dallas, and the Tariff of '42".[5]

In his March 1845 inaugural address, President Polk quoted from the party platform, saying that the U.S. title to Oregon was "clear and unquestionable". Tensions grew, with both sides moving to strengthen border fortifications in anticipation of war. Despite Polk's bold language, he was actually prepared to compromise, and had no real desire to go to war over Oregon. He believed that a firm stance would compel the British accept a resolution agreeable to the United States, writing that "the only way to treat John Bull was to look him straight in the eye". But Polk's position on Oregon was not mere posturing: he genuinely believed that the U.S. had a legitimate claim to the entire region. He rejected British offers to settle the dispute through arbitration, fearing that no impartial third party could be found.[6]

Prime Minister Robert Peel's Foreign Secretary, the Earl of Aberdeen, also had no intention of going to war over a region that was of diminishing economic value to the United Kingdom. Furthermore, the United States was an important trading partner. With the onset of famine in Ireland, the United Kingdom faced a food crisis, and had an increasing need for American wheat. Aberdeen had already decided to accept the U.S. proposal for a boundary along the 49th parallel, and he instructed Richard Pakenham, his minister in the U.S., to keep negotiations open.

A complicating factor in the negotiations was the issue of navigation on the Columbia River. Polk's predecessor, John Tyler, had offered the British unrestricted navigation on the river if they would accept a boundary along the 49th parallel. In the summer of 1845, the Polk administration renewed the proposal to divide Oregon along the 49th parallel, but this time without conceding navigation rights. Because this proposal fell short of the Tyler administration's earlier offer, Pakenham rejected the offer without first contacting London. Offended, Polk officially withdrew the proposal on 30 August 1845 and broke off negotiations. Aberdeen censured Pakenham for this diplomatic blunder, and attempted to renew the dialogue. By then, however, Polk was suspicious of British intentions, and under increasing political pressure not to compromise. He declined to reopen negotiations.[7]

Slogans and war crisis

Meanwhile, many newspaper editors in the United States clamored for Polk to claim the entire region as the Democrats had proposed in the 1844 campaign. Headlines like "The Whole of Oregon or None" appeared in the press by November 1845. In a column in the New York Morning News on December 27, 1845, editor John L. O'Sullivan argued that the United States should claim all of Oregon "by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent". Soon afterwards, the term "Manifest Destiny" became a standard phrase for expansionists, and a permanent part of the American lexicon. O'Sullivan's version of "Manifest Destiny" was not a call for war, but such calls were soon forthcoming.

In his annual address to Congress on December 2, 1845, Polk recommended giving the British the required one-year notice of the termination of the joint occupation agreement. In Congress, Democratic expansionists from the Midwest, led by Senators Lewis Cass of Michigan, Edward A. Hannegan of Indiana, and William Allen of Ohio, called for war with the United Kingdom rather than accepting anything short of all of Oregon up to 54°40'N. (54°40' was then the southern boundary of the Russian claim to Alaska.) The slogan "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight" appeared by January 1846, driven in part by the Democratic press. The phrase is frequently misidentified as a campaign slogan from the election of 1844, even in many textbooks. Bartlett's Familiar Quotations attributes the slogan to William Allen.[8]

The calls to war were fueled by a number of factors, including traditional distrust of the British and a belief that the U.S. had the better claim and would make better use of the land. Moderates warned that the U.S. could not win a war against the world's greatest power, and that negotiation could still achieve U.S. territorial goals. Although the debate in the U.S. was not strictly divided along party or sectional lines, many who clamored for the 54°40' border were Northerners upset that Polk (a Southern slave owner) had been uncompromising in his pursuit of Texas (a cause deemed favorable to Southern slave owners), but willing to compromise on Oregon. As historian David M. Pletcher noted, "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight" seemed to be directed at the southern aristocracy in the U.S. as much as at the United Kingdom.[9]

Resolution and treaty

Although Polk had called on Congress in December 1845 to pass a resolution notifying the British of the termination of joint occupancy agreement, it was not until 23 April 1846 that both houses complied. The passage was delayed (especially in the Senate) by contentious debate, and ultimately a mild resolution was approved, the text of which called on both governments to settle the matter amicably. By a large margin, moderation had won out over calls for war. Unlike Western Democrats, most Congressmen—like Polk—did not want to fight for 54° 40'. [10]

The Polk administration then made it known that the British government should offer terms to settle the issue. Time was of the essence, because it was well known that the Peel government would fall with the impending repeal of the corn laws in the United Kingdom, and then negotiations would have to begin again with a new ministry. Aberdeen and Louis McLane, the American minister in the United Kingdom, quickly worked out a compromise and sent it to the United States. There, Pakenham and U.S. Secretary of State James Buchanan drew up a formal treaty, known as the Oregon Treaty, which was ratified by the Senate on 18 June 1846 by a vote of 41–14. The border was set at the 49th parallel, the original U.S. proposal, with navigation rights on the Columbia River granted to British subjects living in the area. Senator William Allen, one of the most outspoken advocates of the 54° 40' claim, felt betrayed by Polk and resigned his chairmanship of the Foreign Relations Committee.

The terms of the Oregon Treaty were essentially the same ones that had been rejected by the British two and a half years earlier, and thus represented a diplomatic victory for Polk. However, Polk has often been criticized for his handling of the Oregon question. Historian Sam W. Haynes characterizes Polk's policy as "brinkmanship" which "brought the United States perilously close to a needless and potentially disastrous conflict". David M. Pletcher notes that while Polk's bellicose stance was the by-product of internal American politics, the war crisis was "largely of his own creation" and might have been avoided "with more sophisticated diplomacy".[11]

See also

- Pig War — ambiguities in the wording of the Oregon Treaty regarding the route of the boundary, which was to follow "the deepest channel" out to the Strait of Juan de Fuca and beyond to the open ocean resulted in another boundary dispute in 1859 over the San Juan Islands. The dispute was also peacefully resolved after a decade of confrontation and military bluster during which the local British authorities consistently lobbied London to seize back the Puget Sound region entirely, as the United States were busy elsewhere with the Civil War. The San Juans dispute was not resolved until 1870, when the American-preferred marine boundary via Haro Strait, to the west of the islands, rather than the British preference for Rosario Strait which lay to their east, was chosen by the arbitrator (the German Emperor).

- Alaska Boundary Dispute

In popular culture

- 54-40, a Canadian rock band, takes its name from the slogan "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight".

- 54-40 or Fight by Emerson Hough was a 1909 bestselling American novel about the Oregon crisis

- 54-40 is a song by the Seattle grunge era band Dead Moon

- In the Twilight Zone episode "A Kind of Stopwatch" the man in the bar who gives the main character a stop watch that can freeze time is first asked "What do you say, old man?" and replies with "What do I say, well I say fifty-four forty or fight"

Historical maps

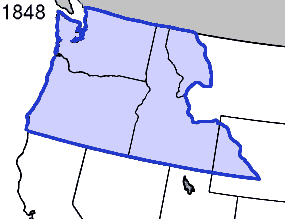

The boundary between British and American territory was shown differently in maps at the time:

- 1841 map of the Oregon Territory.jpg

An 1841 American map showing the 54°40' line near Fort Simpson as the boundary

- Arrowsmith Oregon Country.jpg

An 1844 British map showing the Columbia River as the boundary

- 1846 Oregon territory.jpg

An 1846 map showing the 49th parallel as the boundary through Vancouver Island

- OrBoundaryMapDetached.jpg

An undated map showing the detached territory option proposed by the British

Notes

- ↑ Oregon History: Land-based Fur Trade and Exploration

- ↑ Ewing Young Route. compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White.

- ↑ Salem Online History: Salem's Historic Figures

- ↑ Pletcher, pp. 109–110. The phrase "wise and masterly inactivity", which Calhoun used more than once, originated with Sir James Mackintosh. (source)

- ↑ Rosenboom, p. 132.

- ↑ Polk did not desire war, believed the Oregon claim: Haynes, p. 118. John Bull quote: Pletcher, p. 328. Rejects arbitration: Pletcher, p. 322.

- ↑ Pletcher, pp. 237–249, 296–300; Haynes, pp. 118–120.

- ↑ Both Pletcher (p. 223) and Rosenboom (p. 132) note that the slogan was not used in the election. Pletcher also notes that many textbooks get this wrong. See also E.A. Miles, "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight": an American Political Legend, Mississippi Valley Historical Review 44(2), September 1957, pp. 291–309, and Hans Sperber, "Fifty-four Forty or Fight": Facts and Fictions, American Speech 32(1), February 1957, pp. 5–11.

- ↑ Pletcher, pp. 335–37.

- ↑ Pletcher, pp. 351.

- ↑ Diplomatic victory for Polk, Haynes p. 136; brinkmanship, Haynes p. 194; Pletcher quote, p. 592.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Haynes, Sam W. James K. Polk and the Expansionist Impulse. Arlington: University of Texas, 1997.

- Pletcher, David M. The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1973.

- Rosenboom, Eugene H. A History of Presidential Elections: From George Washington to Richard M. Nixon. Third edition. New York: Macmillan, 1970.

External links

Party platform and speeches

- 1844 Democratic platform, which asserted that the U.S. "title to the whole of the Territory of Oregon is clear and unquestionable"

- Polk's March 1845 inaugural address, in which he reasserted the "clear and unquestionable" claim

- Polk's December 1845 message to Congress, in which he called for the end of the joint occupation of Oregon

Political cartoons from Harper's Weekly, 1846

- "Polk's Dream", in which the Devil, disguised as Andrew Jackson, advises Polk to fight for the 54°40' line

- "Present Presidential Position", in which the Democratic Party's "jackass" is standing on the 54°40' line

- "Ultimatum on the Oregon Question", Polk talks with Queen Victoria, while others make comments

- "War! or No War!", two Irish immigrants face off over the boundary question

Other

- Fifty-Four Forty or Fight at About.com, an example of a reference that mistakenly describes the phrase as an 1844 campaign slogan

- Another reference work that mistakenly ascribes the slogan Fifty-Four Forty or Fight to Polk is the Encyclopædia Britannica. URL last accessed December 16, 2005.

- 54-40 or Fight shows the quilt block named after the slogan. In this time period, women frequently used quilts to express their political views.

|

Pioneer History of Oregon (1806–1890) |

|---|---|

| Topics |

American Fur Company · Executive Committee · Ferries · Hudson's Bay Company · Oregon boundary dispute · Oregon Country · Oregon Lyceum · Oregon missionaries · Oregon Spectator · Oregon Territory · Oregon Trail · Oregon Treaty · Pacific Fur Company · Provisional Government |

| Events |

Treaty of 1818 · Russo-American Treaty · Willamette Cattle Company · Champoeg Meetings · Whitman massacre · Cayuse War · Donation Land Claim Act · Rogue River Wars · Oregon Constitutional Convention |

| Places |

Barlow Road · Champoeg · Fort Astoria · Fort Dalles · Fort Vancouver · Fort William · French Prairie · Methodist Mission · Oregon City · Oregon Institute · Whitman Mission |

| People |

George Abernethy · Ira L. Babcock · Sam Barlow · François Norbert Blanchet · Tabitha Brown · Abigail Scott Duniway · Philip Foster · Peter French · Joseph Gale · William Gilpin · David Hill · Jason Lee · Asa Lovejoy · John McLoughlin · Joseph Meek · Ezra Meeker · John Minto · Robert Newell · Joel Palmer · Sager orphans · Henry H. Spalding · Marcus Whitman · Narcissa Whitman · Ewing Young |

| Oregon History |

Native Peoples History · History to 1806 · Pioneer History · Modern History |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.