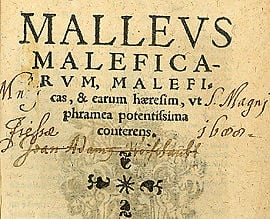

Malleus Maleficarum

The Malleus Maleficarum[2] or Das Hexenhammer (Latin/German for "The Hammer of Witches") is arguably the most infamous medieval European treatise on identifying, characterizing, and combating witchcraft, and has likely been the cause of more pain, torment and death than virtually any other book in the Christian textual corpus. It was written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger with the explicit endorsement of Pope Innocent VIII, who desired "that all heretical depravity should be driven far from the frontiers and bournes of the Faithful,"[3] and was first published in Germany in 1487.[4] Though it was eventually banned by the Vatican, it remained a popular tome among both Catholic and Protestant witch-hunters, eventually selling out over thirty editions throughout the two hundred years that it was in print.[5]

It was the culmination of a long history of medieval theological treatises on witchcraft, the most famous (of these earlier works) being the Formicarius by Johannes Nider in 1435-1437.[6] The main purpose of the Malleus was to systematically refute all arguments against the reality of witchcraft,[7] refute those who expressed even the slightest skepticism about the propriety of the inquisition, to prove that witches were more often woman than men,[8] and to educate magistrates on the procedures that could "unmask" and convict these demonic heretics.[9]

Composition

In the late medieval period (1100-1500 C.E.), the Roman Catholic Church was riven by controversy. Various antipopes vied with the Vatican for ecclesiastical legitimacy, theological positions branded as heretical (including those held by the Catharites, Waldenses and Hussites) were vigorously persecuted, and, in general, the spiritual malaise that came to prompt the Protestant Reformation was becoming steadily more pronounced. One response to these various (and related) crises was an overall shift towards conservatism, insularity and a type of religious xenophobia, which culminated in the persecution of various individuals and groups deemed dangerous by the religious authorities. It was in this context that, on December 5, 1484, Pope Innocent VIII issued the bull Summis desiderantes affectibus ("Desiring with Supreme Ardor"), which authorized two zealous German Inquisitors (Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger) to act as they saw fit in combating the scourge of heresy, witchcraft, and immorality:[10].

- Wherefore We, as is Our duty, being wholly desirous of removing all hindrances and obstacles by which the good work of the Inquisitors may be let and tarded, as also of applying potent remedies to prevent the disease of heresy and other turpitudes diffusing their poison to the destruction of many innocent souls, since Our zeal for the Faith especially incites us, lest that the provinces, townships, dioceses, districts, and territories of Germany, which We had specified, be deprived of the benefits of the Holy Office thereto assigned, by the tenor of these presents in virtue of Our Apostolic authority We decree and enjoin that the aforesaid Inquisitors [Kramer and Sprenger] be empowered to proceed to the just correction, imprisonment, and punishment of any persons, without let or hindrance, in every way as if the provinces, townships, dioceses, districts, territories, yea, even the persons and their crimes in this kind were named and particularly designated in Our letters. Moreover, for greater surety We extend these letters deputing this authority to cover all the aforesaid provinces, townships, dioceses, districts, territories, persons, and crimes newly rehearsed, and We grant permission to the aforesaid Inquisitors, to one separately or to both, as also to Our dear son John Gremper, priest of the diocese of Constance, Master of Arts, their notary, or to any other public notary, who shall be by them, or by one of them, temporarily delegated to those provinces, townships, dioceses, districts, and aforesaid territories, to proceed, according to the regulations of the Inquisition, against any persons of whatsoever rank and high estate, correcting, mulcting, imprisoning, punishing, as their crimes merit, those whom they have found guilty, the penalty being adapted to the offence.[11]

This bull, whose promulgation had been indirectly requested by Heinrich Kramer, prompted the composition of the Malleus Maleficarum in 1486. The text has traditionally been ascribed to Heinrich Kramer (Latinized as "Heinrich Institoris") and Jacob Sprenger, who were both members of the Dominican Order employed as Inquisitors by the Catholic Church.[12] Despite the text's official attribution, modern scholars believe that Jacob Sprenger contributed little (if anything) to the work besides his illustrious name.[13]

Kramer (and possibly Sprenger) submitted the Malleus Maleficarum to the University of Cologne’s Faculty of Theology in 1487, hoping for an endorsement that would lend the text a further air of legitimacy. Instead, the faculty condemned it as being both unethical and illegal. In spite of this rebuff, Kramer proceeded to insert a fraudulent endorsement from the University into subsequent print editions of the text.[14] In a similar manner, most versions of the Malleus also include the full text of the Summis desiderantes affectibus bull, an inclusion that implies papal sanction, despite the fact that the papal statement predated the text itself.[15]

Regardless of less-than-stellar reception the text received upon its initial publication, it gradually became one of first (and most influential) handbooks for Protestant and Catholic witch-hunters in late medieval and early modern Europe.[16] Between the years 1487 and 1520, the work sold out a total of sixteen editions, which led to an additional sixteen being printed and sold in the following hundred and fifty years.[17]

Contents

In general, the Malleus Maleficarum presents a relatively overall theology/demonology, asserting that three elements are necessary for existence of witchcraft: the evil-intentioned witch (whose particular moral failings impel her to sin), the intercession of the Devil (who is the proximate cause of the witch's supernatural abilities), and the (implicit) permission of God (who is the ultimate cause of all actions).[18] In terms of textual organization, the treatise is divided up into three sections: the first "presents theoretical and theological arguments for the reality of witchcraft" (aiming to silence critics of the Inquisition's efforts); the second describes the actual applications of witchcraft, and compiles various remedies that can be used by those "bewitched"; finally, the third section provides instructions to judges, in order to assist them in their "divine mission" to confront and combat witchcraft.[19] Superseding this organizational principle, each of these three sections is also united by a ubiquitous emphasis on providing textual definitions and practical guidelines for classifying witchcraft and identifying witches.

In spite of the document's place of primacy in the history of the European "witch-craze," the Malleus can hardly be called an original text, for it relied heavily upon earlier works by Visconti, Torquemada and, most famously, Johannes Nider (the Formicarius (1435)).[20] However, these inter-textual parallels merely indicate the "canonicity" of demonological beliefs in the late Middle Ages. As Krause notes, "[d]emonology soon claimed for itself an authoritative status as demonologists interpreted puzzling features of witchcraft in light of the work of other demonologists. In the Malleus maleficarum, references to Johannes Nider’s Formicarius reside comfortably alongside passages from Aquinas, both texts serving as authorities. ... Demonology had become in effect its own self-legitimating discourse."[21]

Section I

Section I argues that, because the Devil exists and has the power to do astounding things, witches (immoral women) exist to make these powers manifest. However, it avoids the theological problem of under-representing the power of the Divine by arguing that even these malevolent actions are performed with the permission of God.[22] This repugnantly misogynistic theodicy is argued at great length in the text:

- God in justice permits evil and witchcraft to be in the world, although He is Himself the provider and governor of all things; ... But God is the universal controller of the whole world, and can extract much good from particular evils; as through the persecution of the tyrants came the patience of the martyrs, and through the works of witches come the purgation or proving of the faith of the just, as will be shown. Therefore it is not God's purpose to prevent all evil, lest the universe should lack the cause of much good. Wherefore S. Augustine says in the Enchiridion: So merciful is Almighty God, that He would not allow any evil to be in His works unless He were so omnipotent and good that He can bring good even out of evil.[23]

The central role that the text assigns to women in bring evil into the world requires that the author(s) make certain (defamatory) ontological assumptions about the natural qualities of females:

- All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable. See Proverbs xxx: There are three things that are never satisfied, yea, a fourth thing which says not, It is enough; that is, the mouth of the womb. Wherefore for the sake of fulfilling their lusts they consort even with devils. More such reasons could be brought forward, but to the understanding it is sufficiently clear that it is no matter for wonder that there are more women than men found infected with the heresy of witchcraft. And in consequence of this, it is better called the heresy of witches than of wizards, since the name is taken from the more powerful party. And blessed be the Highest Who has so far preserved the male sex from so great a crime: for since He was willing to be born and to suffer for us, therefore He has granted to men the privilege.[24][25]

Section II

In Section II, the author(s) begin to address more practical matters by discussing actual cases. The section begins by exposing the multifarious powers of witches, and then goes on to detail their recruitment strategies.[26] In doing so, it places the blame squarely upon these duplicitous females, suggesting that they purposefully lead moral women astray, either by causing disasters in their lives (which could impel them to consult the arcane knowledge of a witch) or by introducing young maidens to physically appealing demons.[27] Given the assumed weakness of spirit introduced above, the second approach would have been seen as virtually infallible. This section also explores the mechanics of malefic spellcraft, lists some of the dreadful offenses perpetrated by these evil-doers (including promoting infirmity,[28] causing damage to livestock,[29] sacrificing children,[30] and even stealing a man's "virile member"[31]) and concludes by instructing the reader in various defensive techniques that can be used against these powers (whether one is aiming to avoid ensorcellment or to mitigate the effects of existing curses).[32]

Section III

Unlike the sensationalistic visions proposed in the previous sections, Section III is comparatively dry and legalistic, as describes (in great detail) the correct procedure for prosecuting a suspected witch. Therein, the author(s) offer a step-by-step guide to conducting a witch trial, from the method of initiating the process and assembling accusations, to the proper forms of defensive council, to the interrogation of witnesses and the formal laying of charges against the accused.[33] A small snippet from the chapter on appropriate forms of inquisition is sufficient for establishing the overall tone and stance taken by this section as a whole:

- While the officers are preparing for the questioning, let the accused be stripped; or if she is a woman, let her first be led to the penal cells and there stripped by honest women of good reputation. And the reason for this is that they should search for any instrument of witchcraft sewn into her clothes; for they often make such instruments, at the instruction of devils, out of the limbs of unbaptized children, the purpose being that those children should be deprived of the beatific vision. And when such instruments have been disposed of, the Judge shall use his own persuasions and those of other honest men zealous for the faith to induce her to confess the truth voluntarily; and if she will not, let him order the officers to bind her with cords, and apply her to some engine of torture; and then let them obey at once but not joyfully, rather appearing to be disturbed by their duty. Then let her be released again at someone's earnest request, and taken on one side, and let her again be persuaded; and in persuading her, let her be told that she can escape the death penalty.[34]

Unfortunately for the women accused in these tribunals, the procedures advocated by the Malleus made it nearly impossible for them to emerge with a not guilty verdict. For instance, women who did not cry during their trials were automatically believed to be witches.[35] Likewise, those who would not confess to their "crimes" were assumed to be supernaturally fortified by a "spell of silence," a demonic charm that would allow them to brave the questions and tortures directed at them.

- It is here that one can take full measure ofd emonology’s logic of certainty, its self-confirming capacity: if the suspected witch confesses, then guilt is firmly established; if the suspect does not confess, she is bewitched but guilty nonetheless. Demonologists push this logic of damned if you do, damned if you don’t, one step further: a silent or otherwise resistant person is even more guilty than a defendant who confesses easily.[36]

Major themes

Misogyny

Misogyny runs rampant in the Malleus Maleficarum. The treatise singled out women as witches as specifically inclined for witchcraft, because they were susceptible to demonic temptations through their manifold weaknesses. It was believed that they were weaker in faith and were more carnal than men [37]. Most of the women accused as witches had strong personalities and were known to defy convention by overstepping the lines of proper female decorum [38]. After the publication of the Malleus, most of those who were prosecuted as witches were women [39]. Indeed, the very title of the Malleus Maleficarum is feminine, which alludes to the fact that it was women who were the evildoers. Otherwise, it would be the Malleus Maleficorum, the masculinized version of the Latin noun maleficium.

The Malleus Maleficarum was heavily influenced by humanistic ideologies. The ancient subjects of astronomy, philosophy, and medicine were being reintroduced to the west at this time, as well as a plethora of ancient texts being rediscovered and studied. The Malleus often makes reference to the Bible, Aristotelian thought, and is heavily influenced by the philosophies of Neo-Platonism [40]. It also mentions astrology and astronomy, which had recently been reintroduced to the West by the ancient works of Pythagoras [41].

Reasons for popularity in the Late Middle Ages

The Malleus Maleficarum was able to spread throughout Europe so rapidly in the late fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth century due to the innovation of the printing press in the middle of the fifteenth century by Johannes Gutenberg. That printing should have been invented thirty years before the first publication of the Malleus which instigated the fervor of witch hunting, and, in the words of Russell, "the swift propagation of the witch hysteria by the press was the first evidence that Gutenberg had not liberated man from original sin." [42] The Malleus is also heavily influenced by the subjects of divination, astrology, and healing rituals the Church inherited from antiquity [43].

The late fifteenth century was also a period of religious turmoil, for the Protestant Reformation was but a few decades in the future. The Malleus Maleficarum and the witch craze that ensued took advantage of the increasing intolerance of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Europe where the Protestant and Catholic camps each zealously strove to maintain the purity of faith [44].

Consequences

In between 1487 and 1520, twenty editions of the Malleus were published, and another sixteen editions were published between 1574 to 1669 [45]. Popular accounts suggest that the extensive publishing of the Malleus Maleficarum in 1487 launched centuries of witch-hunts in Europe, in which www.malleusmaleficarum.org [3] estimates that between 600,000 to 9,000,000 people (mostly women) were killed because they were accused as witches. However, this attributes (at the low end of these estimates) to this one book 1500% of the currently accepted scholarly estimate of the total death toll of all the witch trials in Europe between 1450 and 1700. Also, as some researchers have noted, the fact that the Malleus was popular does not imply that it accurately reflected or influenced actual practice; one researcher compared it to confusing a "television docu-drama" with "actual court proceedings." Estimates about the impact of the Malleus should thus be weighed accordingly.

Notes

- ↑ The English translation is from this note to Summers' 1928 introduction.

- ↑ Translator Montague Summers consistently uses "the Malleus Maleficarum" (or simply "the Malleus") in his 1928 and 1948 introductions. [1] [2]

- ↑ Pope Innocent VIII, Summis desiderantes affectibus, translated by Montague Summers and originally published in "The Geography of Witchcraft," by Montague Summers, pp. 533-6 (Kegan Paul). Accessed online at: http://www.malleusmaleficarum.org/mm00e.html. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ↑ Jolly (2002), 239

- ↑ Parker, 24.

- ↑ Bailey (2003), 30

- ↑ This was a common theme in the texts of the era. Krause notes a similar pattern in Jean Bodin's De la démonomanie des sorciers (1580), which "attacks the skeptics of demonology as much as the legions of demons and execrable witches supposedly plotting universal destruction" (327).

- ↑ This gendered understanding of demonic power was a central element in the Malleus, as described in Stephens (1998); Andersen (1992); and Broedel (2003).

- ↑ Jolly, 240

- ↑ Russell, 229

- ↑ Pope Innocent VIII, Summis desiderantes affectibus, translated by Montague Summers and originally published in "The Geography of Witchcraft," by Montague Summers, pp. 533-6 (Kegan Paul). Accessed online at: http://www.malleusmaleficarum.org/mm00e.html. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ↑ In this post, their primary role was to defend the faith against heresy, where "heresy" can be defined as "an error in understanding and of faith in the Catholic religion, ultimately discernible by God alone" (Broedel (2003), 20). See also: Inquisition in the Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 18, 2007.

- ↑ Russell (1972), 230; Krause, 345 ff. 14.

- ↑ History of the Malleus Maleficarum by Jenny Gibbons. Retrieved July 18, 2007. See also: "Witchcraft" in the Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ See, for example, the Montague Summers translation.

- ↑ Henningsen (1980), 15; see also "Witchcraft" in the Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Parker, 24.

- ↑ Russell, 232

- ↑ Smith, 88.

- ↑ Russell, 279

- ↑ Krause, 335.

- ↑ Broedel, 22

- ↑ Part I: Question XII, Malleus Maleficarum, retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ↑ Part I: Question VI, Malleus Maleficarum, retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ↑ Andersen offers a cogent and well-considered critique to this section, noting that "[i]n their effort to render Woman depraved and prone to witchcraft, they read Proverbs in a lurid light. The Latin os vulvae, meaning the entrance to the womb, is a faulty translation of 'the barren womb' that one finds in all texts derived from the Masoretic, which served for the Hebrew Bible. ... No implications of 'carnal lust' or 'insatiable' sexual appetite are made in this verse" (Andersen, 715-716).

- ↑ Broedel, 30

- ↑ Broedel, 30

- ↑ Part II: Question I, Chapter IX, Malleus Maleficarum, retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ↑ Part II: Question I, Chapter XIV, Malleus Maleficarum, July 19, 2007.

- ↑ Part II: Question I, Chapter VII, Malleus Maleficarum, retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ↑ Part II: Question I, Chapter VII, Malleus Maleficarum, retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ↑ MacKay, 214. Malleus Maleficarum, Part II: Question II (passim), retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ↑ Broedel, 34

- ↑ Part III: Second Head, Question XIV, Malleus Maleficarum, retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ↑ MacKay, 502

- ↑ Krause, 332-333.

- ↑ Bailey, 49

- ↑ Bailey, 51

- ↑ Russell, 145

- ↑ Kieckhefer (2000), 145

- ↑ Kieckhefer, 146

- ↑ Russell, 234

- ↑ Jolly, 77

- ↑ Henningsen (1980), 15

- ↑ Russell, 79

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bailey, Michael David. Battling Demons: Witchcraft, Heresy, and Reform in the Late Middle Ages. Pennsylvania State University Press. University Park, PA. 2003

- Broedel, Hans Peter. The Malleus Maleficarum: and the construction of Witchcraft, Theology and Popular Belief. Manchester University Press. New York, NY. 2003

- Flint, Valerie. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ. 1991

- Hamilton, Alastair (May 2007). Review of Malleus Maleficarum edited and translated by Christopher S. Mackay and two other books. Heythrop Journal 48 (3): 477-479.

(payment required) - Henningsen, Gustav. The Witches' Advocate: Basque Witchcraft and the Spanish Inquisition. University of Nevada Press. Reno, NV. 1980

- Institoris, Heinrich and Jakob Sprenger (1520). Malleus maleficarum, maleficas, & earum haeresim, ut phramea potentissima conterens. Coloniae: Excudebat Ioannes Gymnicus.

- This is the edition held by the University of Sydney Library. [4]

- Jolly, Karen Louise. Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press. Philadelphia, PA. 2002

- Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England. 2000

- Mackay, Christopher S. (2006). Malleus Maleficarum (2 volumes). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521859778. (Latin) (English) (bibrec) (editor's home page)

- Volume 1 is the Latin text of the first edition of 1486-7 with annotations and an introduction. Volume 2 is an English translation with explanatory notes.

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1972 repr. 1984). Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801492890. (bibrec)

- Summers, Montague (1948 repr. 1971). The Malleus Maleficarum of Kramer and Sprenger, ed. and trans. by Summers, Dover Publications. ISBN 0486228029.

- Thurston, Robert W. (Nov 2006). The world, the flesh and the devil. History Today 56 (11): 51-57. (payment required for full text)

External links

- Malleus Maleficarum - Online version of Latin text and scanned pages of Malleus Maleficarum published in 1580 (Retrieved July 16, 2007)

- Malleus Maleficarum - Full text of the 1928 English translation by Montague Summers. His 1948 introduction is also included. (Retrieved July 16, 2007)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.